Originally Posted by Eric Flaningam

Original translation: TechFlow

This is an article analyzing 30 years of technology company returns, value growth, lessons learned, and future significance.

The next $100 billion company will be different from the last one.

This sounds like an obvious statement, but we can’t help but get caught up in the pattern matching trap of looking for the next Google/Meta/Amazon, or the Uber for industry X, the Airbnb for industry Y, or the AI agent for almost any industry.

Well, to avoid being swept up in the latest trends each week, we must look back. As Churchill once said, "The further back you look, the further you can see."

So I wanted to analyze the largest companies founded in recent history. Don’t get caught up in the narrative, but focus on what the data tells us and, as Mauboussin would say, get an outside perspective!

Causal thinking is an innate narrative form. It can both convincingly predict the future and convincingly explain the past. Our brains are adept at creating simple, understandable narratives to explain what's happening in the world around us.

The second approach is to adopt statistical thinking, often called an external perspective. Instead of weaving a story based on cause and effect, a statistical approach looks at a reference class of similar past cases and analyzes their outcomes. The outcomes for these reference classes are called baseline probabilities.

Therefore, we will delve into:

- Technology value growth data over the past 30 years

- Lessons Learned from Value Growth

- What these lessons mean for technology investing today

TL;DR

- The next $100 billion company will look very different from the past

- Define your trajectory: Is it a home run, a grand slam, or aiming for outer space like in Space Jam?

- Software is like chicken; 80% of it tastes the same.

- “Market size” may be the biggest reason why good investors miss out on great companies

- Companies are often closely tied to the technology waves they rely on

- Finally, I have to say: never underestimate the power of the power law!

Additionally, we launched our Felicis Startup Recruitment Program last week. Check out the sectors we're looking to invest in.

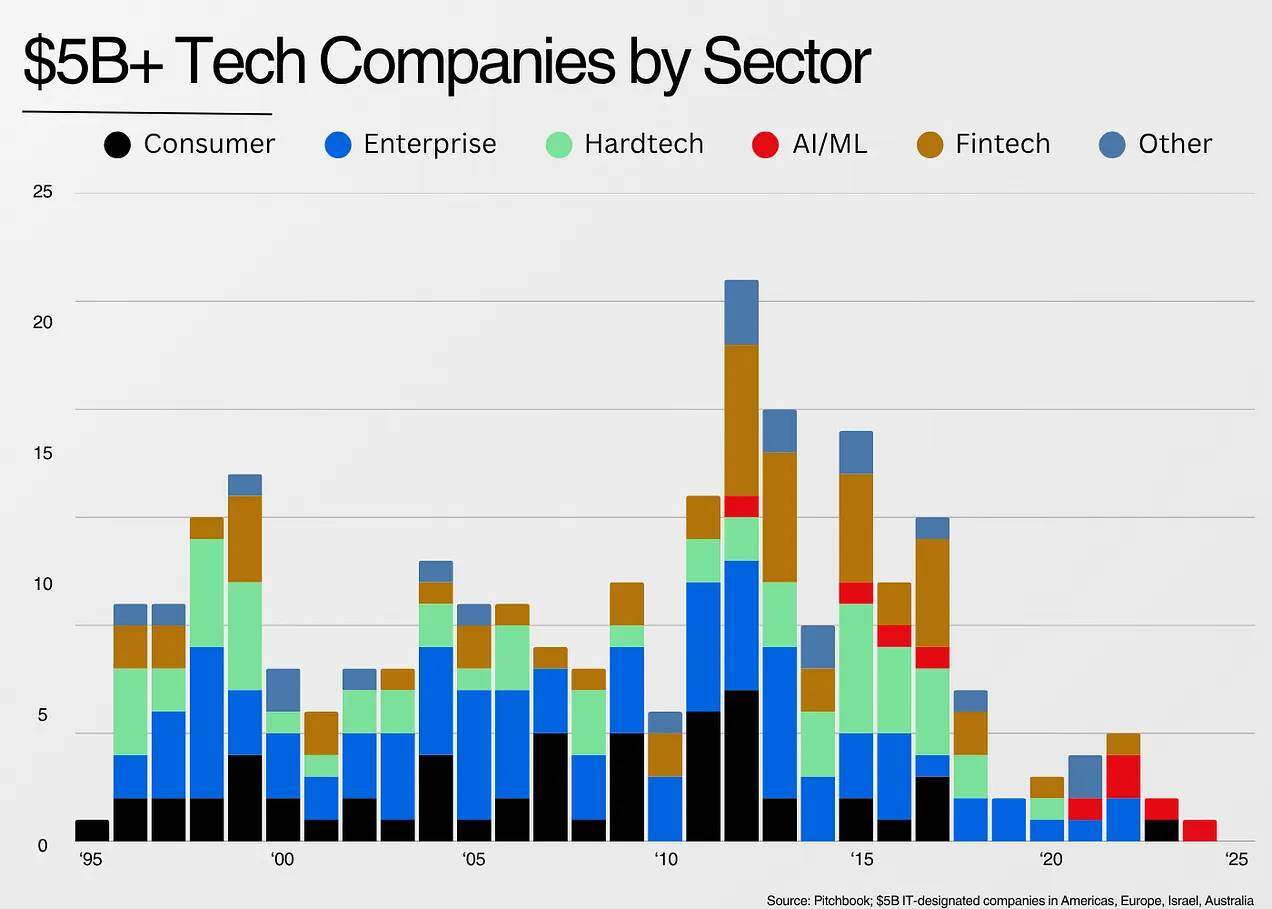

A word about methodology: The vast majority of tech value is concentrated in the largest companies, so I took every company listed on Pitchbook as having an IT value of $5 billion or more founded since 1995. (Note: this excludes Amazon, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple.) I had Claude help categorize these companies, so I think the exact data is directionally accurate, but not substantively accurate.

Let’s get started.

30 Years of Technology Company Return Data

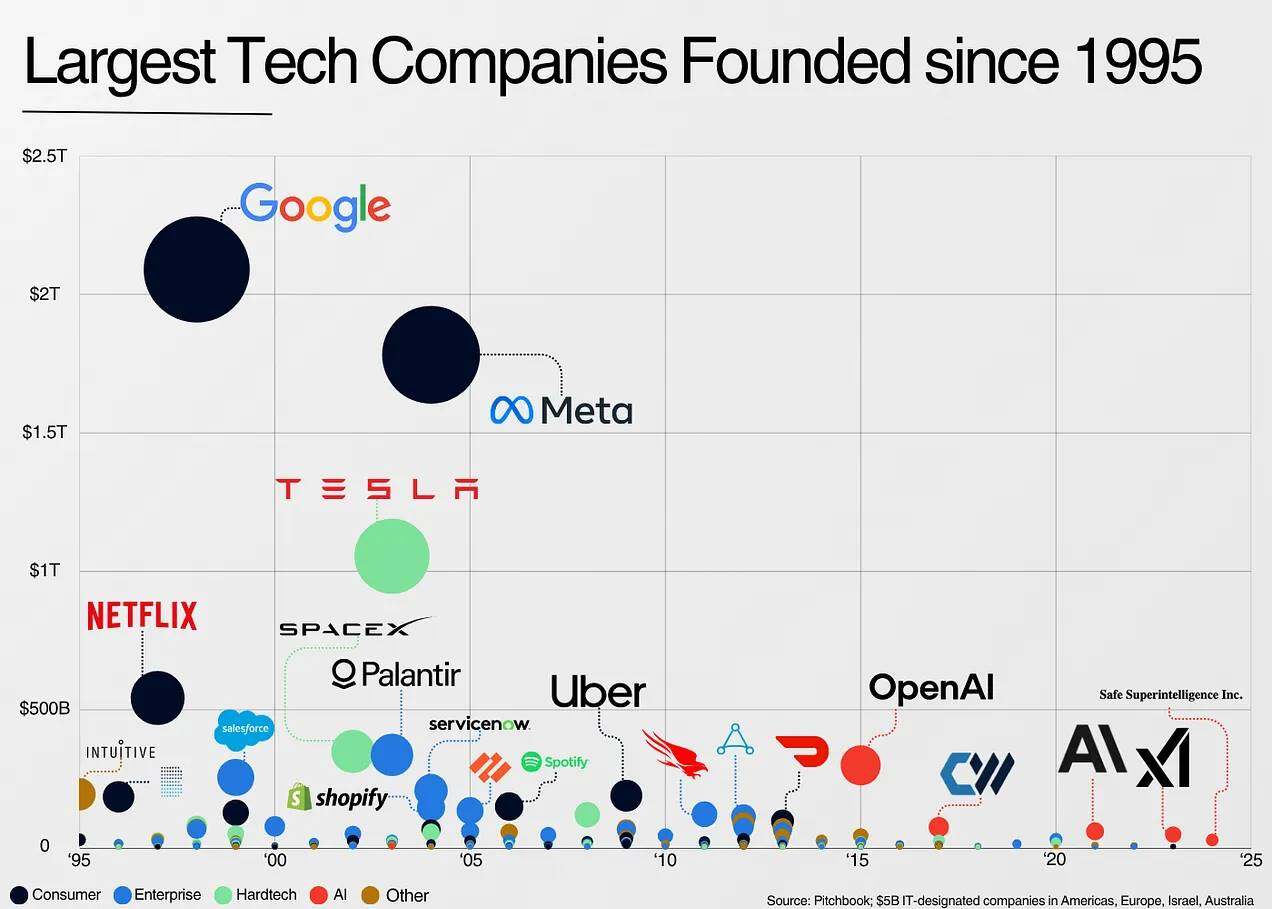

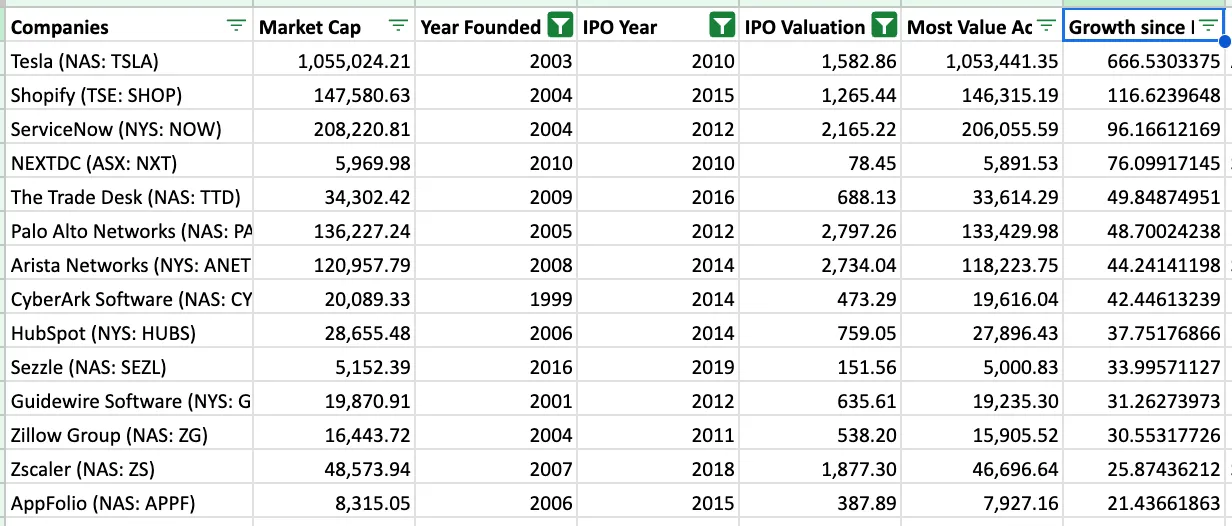

The dataset covers 65 categories, over 300 companies, and $13 trillion in value. Here are the highlights of the most successful companies:

I won’t go into the details of the power law now, but the top seven companies account for nearly 50% of this dataset.

This leads to the first and most important conclusion:

1. The next $100 billion company will look very different from the past

First, the value of technology is primarily driven by unique companies, which are often founded by unique people. Precisely because of their "uniqueness," relying on pattern matching is more likely to make us miss great companies rather than discover them.

If a company has never experienced this, it's hard to imagine its future. How do you estimate the market size of Google in 1998? How do you estimate the market size of Meta in 2004? It's simply impossible.

Take, for example, OpenAI, one of the most unique AI companies currently operating. It began as a nonprofit research lab with no clear technical vision, a founding team that lost its co-founder, and a complex governance structure. Yet, it has steadily grown into one of the most important companies in history. It's the pinnacle of uniqueness.

The most successful companies have no so-called “public comparables”; they are unique. The largest companies often create entirely new categories, which is precisely what makes them so hard to find.

Neil Mehta defines it as finding “the very few founders in the world who will create the majority of the value enjoyed by humanity.”

To start putting some numbers into perspective, take a look at the largest companies founded since 1995:

Most of these companies have either pioneered entirely new industries or reshaped them with such scale that they practically created their own industries (e.g., Tesla).

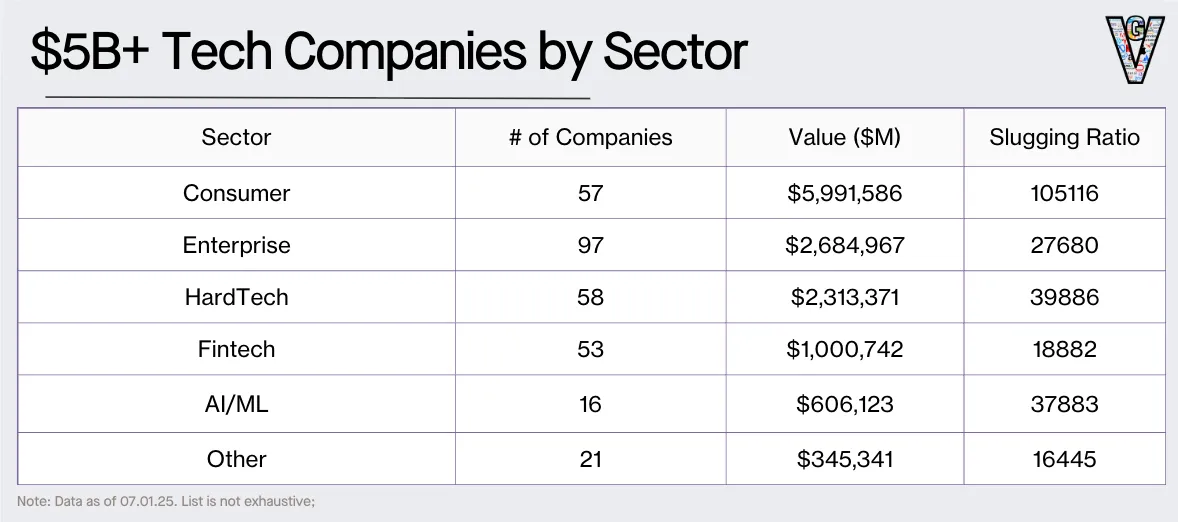

Looking at the data by category reveals the following:

2. Identify the game you're playing: a home run, a grand slam, or a space-based challenge like Space Jam.

If we look back at Mauboussin’s base rate philosophy, I think we need a different mental model for investing in these different categories.

Most value is created by consumer product companies (driven by the power law). However, there are almost twice as many enterprise software companies as consumer product companies.

To illustrate this more visually, I added a column called “Slugging Ratio”, which is the ratio of “total company value/number of companies”, to give an idea of the extent of the power law distribution in different industries.

Over the past 30 years, consumer product companies have often operated in internet-driven markets, with true winner-take-all dynamics. If you happened to invest in one of these giants, the only mistake you could make is underestimating their future size. Yuri Milner's $10 billion investment in Facebook is a case in point.

If a company can truly integrate network effects into its business model, its advantages immediately increase.

Hard tech companies (any company involved in hardware manufacturing) have the second-highest average return, primarily because they face a more challenging environment. These companies typically require more capital, take longer to scale, have more challenging product development, are more susceptible to funding difficulties, and have a harder time disrupting incumbents.

However, if they can break through this speed bottleneck, the market opportunity will be enormous.

However, there is a finite number of consumer product and hard tech companies that can be invested in. This is why enterprise software has become an ideal investment vehicle for the expanding venture capital landscape.

In non-winner-take-all markets, fast-expanding businesses enjoy strong moats and lower operating costs. In an environment with a large number of venture capital funds, there are more winners to chase, more mature markets, and, all in all, much less risk. But if all goes well, there's huge upside. This is a great way to mitigate risk in an inherently high-risk industry.

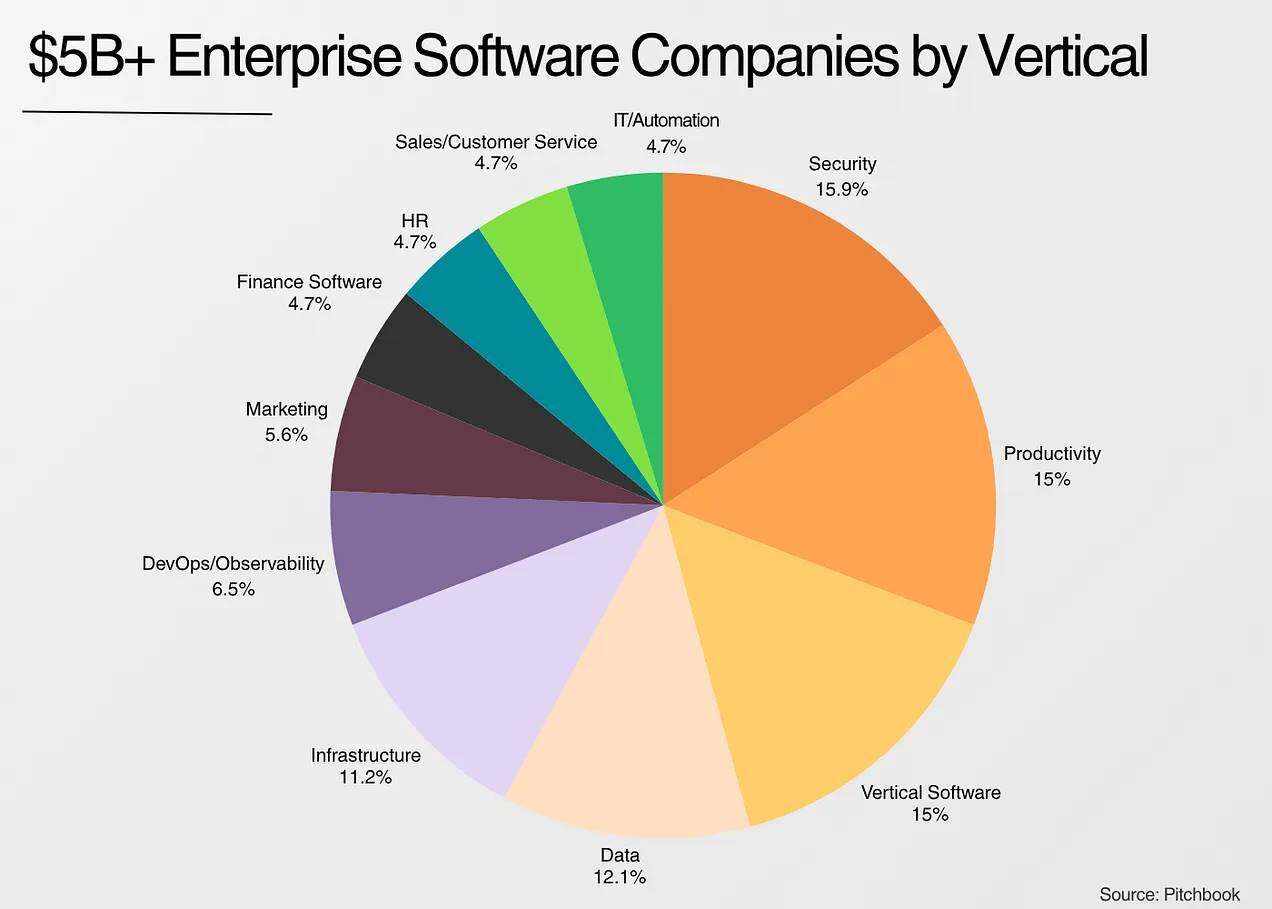

3. Software is like chicken; 80% of it tastes the same

I borrowed a line from Robert Smith, founder of Vista Equity Partners, that said, “Software companies taste like chicken… They sell different products, but 80% of what they do is pretty much the same.”

If we look at most of the largest enterprise software companies, they are either:

- Applications built on databases with unique workflows

- The infrastructure to build these applications

- Securing these applications

This is not to say that these companies are not differentiated, but their differentiation is much more subtle than it appears on the surface. Sales, marketing, and building brand recognition are all as important as, or even more important than, technological differentiation.

In a world where software is increasingly easy to build, functionality can be replicated in days, and AI coding tools are becoming increasingly sophisticated, a technological moat in software may be limited to unique data or integrations.

The key point is that technological differentiation is often not the deciding factor for enterprise software companies.

In this context, I find the “GPT wrapper” argument interesting, which states that AI application companies are simply repackaging LLM. Most enterprise software companies use SQL (or NoSQL) databases and build unique workflows for specific customer segments.

If we look at the largest recent AI enterprise application companies, they are all “large language model wrappers.” But this is exactly the same as the largest enterprise software companies in the past decade, which eventually grew into giants with market capitalizations exceeding $100 billion!

As I mentioned earlier, enterprise software offers lower risk and more predictable opportunities than other categories. However, outside of horizontal enterprise software, market size doesn't seem as important as it appears. "How big can this company get?" and "How big is the market?" are two very different questions.

4. “Market size” may be the biggest reason why good investors miss out on great companies

If there's one thing humans struggle with the most, it's uncertainty. And that's exactly what new markets bring.

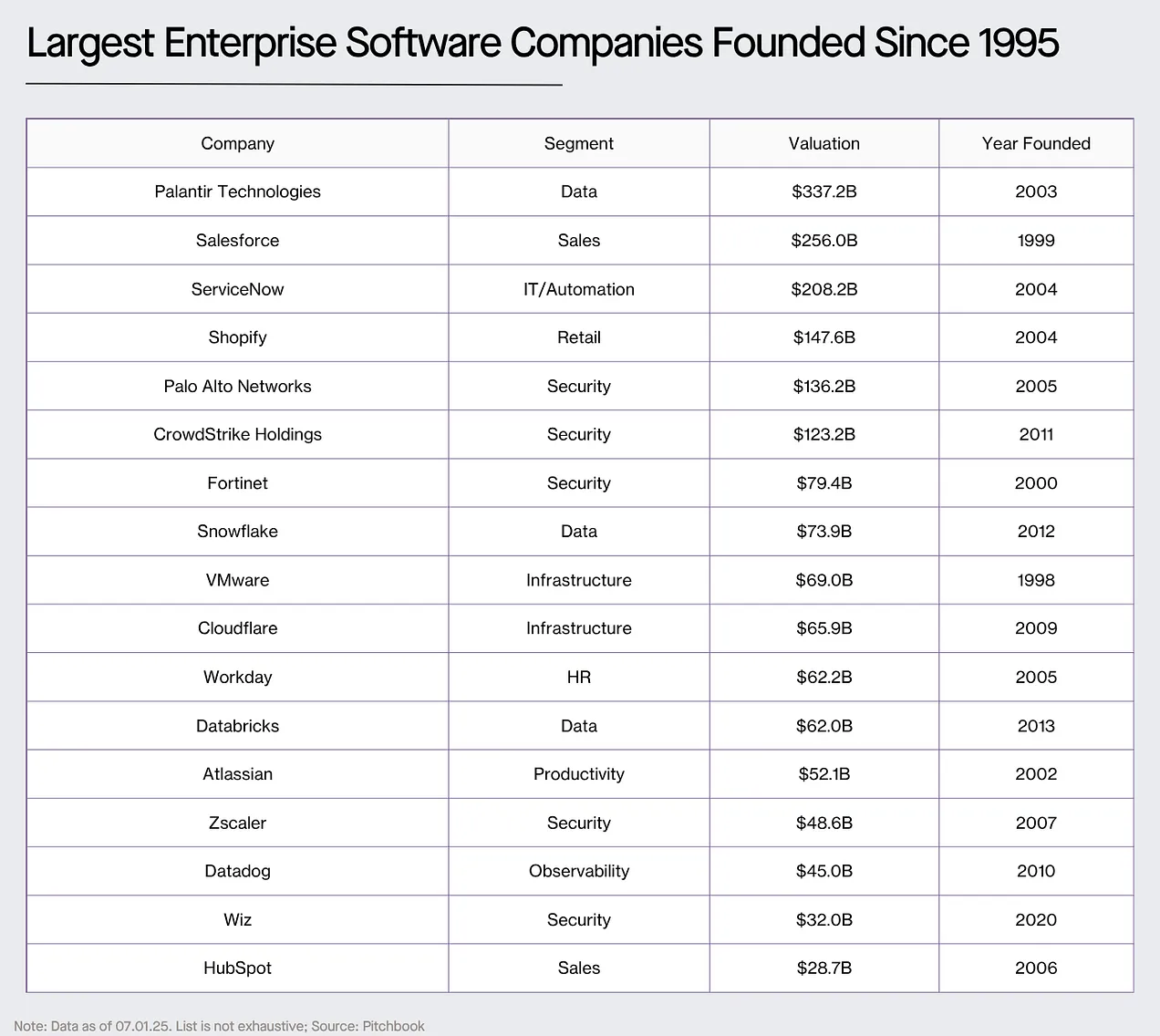

Palantir, Shopify, Uber, and many others have more or less created new markets that didn’t exist before.

Even trying to add certainty to an inherently uncertain problem can lead to foolish behavior.

Take the famous debate between Aswath Damodaran and Bill Gurley about valuing Uber. Gurley concluded that Uber's addressable market might be 25 times larger than Damodaran's initial estimate.

I looked at companies founded since 2010 that have achieved the highest multiple returns on the public markets, arguably a measure of undervaluation.

Some patterns emerged:

- Investors underestimated the market size, especially when investing in market extenders or vertical markets: Shopify, Guidewire, Zillow, AppFolio, etc. were underestimated. Similarly, in the private market, investors also underestimated vertical software companies such as Toast and ServiceTitan.

- As new business models outperform old ones, companies enjoy a tailwind of multiple expansion: Tesla (the most extreme example) and, to a lesser extent, all the software companies on this list have seen their multiples reshaped relative to the incumbents they previously competed with. Tesla alone is now valued at nearly $1 trillion, more than double the combined market capitalization of all major automakers when it entered the market.

- Investors underestimate the power of platforms: ServiceNow, Palo Alto, Crowdstrike, Workday, Atlassian, and Datadog have all expanded their product lines to reach new markets. As software development becomes easier and the technological differences between platforms shrink, customers are increasingly choosing platforms over point solutions. In the age of consolidation, platformization is a good thing!

This is not to say that market size is unimportant, but rather to emphasize that market size can be easily misestimated.

5. Companies are often closely tied to the technology waves they rely on.

If the previous section was the "Market Size" section, this section is the "Why Now?" section. A well-known "Why Now?" question in venture capital is: Why wasn't this company created before? What new revelations now warrant this company's existence?

In most cases, the answer is that a new wave of technology has made the business possible. Today, that wave is artificial intelligence (AI). In the past, it was the internet, then mobile technology, then the convergence of the internet and mobile, and finally cloud computing.

Below we can see the birth dates of $5 billion+ companies by industry:

The Internet connects the world and gives rise to the rise of aggregated business models.

Mobile technology has taken this a step further, putting the internet in everyone’s hands and opening up a new landscape for the consumer market.

Fintech is a rare example of how regulation can drive the development of new technology industries, particularly after the 2010s, when it flourished following the implementation of the Durbin Amendment.

Cloud computing is the most disruptive wave in technology history, allowing companies to build software with credit card payments rather than relying on data centers.

As artificial intelligence (AI) advances, which companies will be ignited and what will they look like?

- AI programming tools are further driving the advancement of cloud computing, enabling not only developers but anyone to create software. This will usher in a software explosion similar to the one that occurred during the cloud computing era.

- AI also unlocks the ability to automate voice and text workflows. We’ve already seen this trend in areas like programming, customer service, and AI-powered recording, but it will expand to many more scenarios in the future.

This has expanded the software market in ways we haven't seen before. For example: no legitimate software company in this dataset has a valuation over $5 billion. Yet Harvey, just three years after its founding, has already reached a $5 billion valuation.

Rex Woodbury offers a great thought experiment about the current state of AI:

I like Alfred Lin's analogy between mobile and the cloud. In the mobile era, a valuable exercise is to break down the features of an iPhone and predict which companies each feature could enable. He gives the example of how GPS enabled delivery drivers to drive around with Google Maps. This gave rise to DoorDash.

The technological wave created a narrow window for new companies to emerge, and we are seeing that window emerging now.

6. What happens next?

Last week, while reading Will and Ariel Durant's History, I came across this sentence: History mocks all attempts to fit it into theoretical patterns or logical frameworks; it constantly defies our generalizations and overturns all rules. History itself is complex and varied, full of wonders and anomalies, like the baroque style.

Perhaps this article is foolish, as it attempts to fit even the most anomaly-based of industries into a logical framework!

What remains constant is human nature. If we analyze it from a reverse perspective, humans often find it difficult to imagine exponential growth, cope with abnormal situations, and deal with uncertainty.

To deal with this uncertainty, our best options are to:

- Understand the "base rate" for your company category (what might happen)

- Understand where differentiation comes from (in software, this is sometimes primarily sales and marketing)

- Treat market sizing as a first principles exercise in solving the problem at hand, rather than a simple pattern matching exercise

- The value of recognizing that each wave of companies is unique and difficult to predict is precisely what makes it so.

Steve Jobs said of computers: "I think one of the things that really distinguishes us from the higher primates is that we are tool makers... To me, the computer is the most amazing tool we have ever invented. It's the bicycle for our minds."

Jobs was right. Computers unleashed a wave of unprecedented creativity.

We are currently witnessing the birth of the greatest bicycle for the mind ever created. It is an exciting time to be alive!

- 核心观点:下一家千亿公司将颠覆既有模式。

- 关键要素:

- 前7大公司占30年科技价值50%。

- 消费品/硬科技主导高回报赛道。

- AI技术浪潮催生新市场窗口期。

- 市场影响:倒逼投资者突破传统估值框架。

- 时效性标注:长期影响。