Vitalik Buterin: Governance Beyond Token Voting

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Original: Moving beyond coin voting governance

Special thanks to Karl Floersch, Dan Robinson, and Tina Zhen for their feedback and review. See Notes on Blockchain Governance, Governance, Part II: Plutocrats Are Still Bad, On Collusion and Coordination, Good and Bad, for early thinking on similar topics.

An important trend in the blockchain space over the past year has been the transition from focusing on decentralized finance (DeFi) to simultaneously thinking about decentralized governance (DeGov). While 2020 has often been widely and justifiably hailed as the year of DeFi, in the year since, the increasing complexity and capabilities of the DeFi projects that make up the trend have led to a decentralization of dealing with this complexity. There is growing interest in global governance. There are some examples inside Ethereum. YFI, Compound, Synthetix, UNI, Gitcoin, and other projects have all launched and even started using some kind of DAO. The same is true outside of Ethereum, with discussions about infrastructure funding proposals in Bitcoin Cash, infrastructure funding voting in Zcash, etc.

secondary title

DeGov is necessary

Since the 1996 Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, there has been a key unresolved contradiction in what could be called a cyberpunk ideology. On the one hand, cyberpunk values were all about using cryptography to reduce coercion and maximize the efficiency and reach of the main non-coercive coordination mechanisms of the time: private property and markets. On the other hand, the economic logic of private property and markets is for those who can be"break down"An activity optimized for repetitive one-to-one interactions, the infosphere, in which art, documents, science, and code are produced and consumed through irreducible one-to-many interactions, is the exact opposite of that.

In such an environment, there are two inherent key issues that need to be addressed.

Funding public goods: How to fund projects that are valuable to broad, unselected segments of the community, but often have no business model (e.g. layer 1 and layer 2 protocol research, client development, documentation... ..)?

Protocol maintenance and upgrade: how to upgrade the protocol, and how to conduct regular maintenance and adjustment operations on long-term unstable parts of the protocol (such as the list of secure assets, sources of price oracles, and multi-party computing key holders), how is it negotiated? ?

Early blockchain projects largely ignored both of these challenges, pretending that the only important public good was network security, which could be achieved with a single algorithm fixed in perpetuity and paid for in fixed proof-of-work rewards. This funding situation was initially possible due to the massive rise in the price of Bitcoin in 2010-2013, then the ICO boom in 2014-2017, and the simultaneous second crypto bubble in 2014-2017, all of which made the ecosystem Enough abundance to temporarily mask huge market inefficiencies. Long-term governance of the commons is equally neglected: Bitcoin goes the path of extreme minimalism, focusing on providing a fixed supply of money and ensuring support for layer 2 payment systems like the Lightning Network, and nothing more. Ethereum continues to evolve harmoniously (with one major exception) due to the strong legitimacy of its pre-existing roadmap (basically: "proof of stake and sharding"), while projects requiring more complex application layers do not yet exist .

But now, that luck is getting worse, and the challenge of coordinating protocol maintenance and upgrades, and funding documentation, research, and development while avoiding the risk of centralization becomes a top priority.

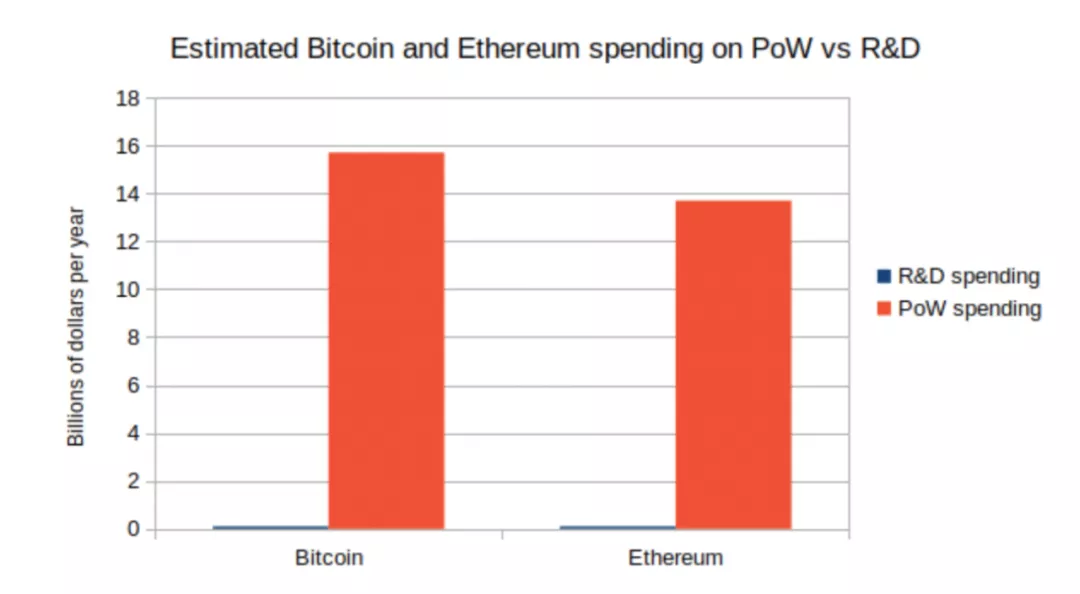

DeGov needs to fund public goods

It is necessary to take a step back and look at the absurdity of the present. The daily mining issuance reward from Ethereum is approximately 13,500 ETH, or approximately $40 million per day. Transaction fees are equally high; non-EIP-1559 burns are still around 1,500 ETH (~$4.5 million) per day. As a result, billions of dollars are spent annually to fund cybersecurity. Now, what is the budget of the Ethereum Foundation? About $30-60 million per year. There are non-EF players (such as Consensys) contributing to development, but they are not large. The situation is similar with Bitcoin, where less money may be spent on non-secure public goods.

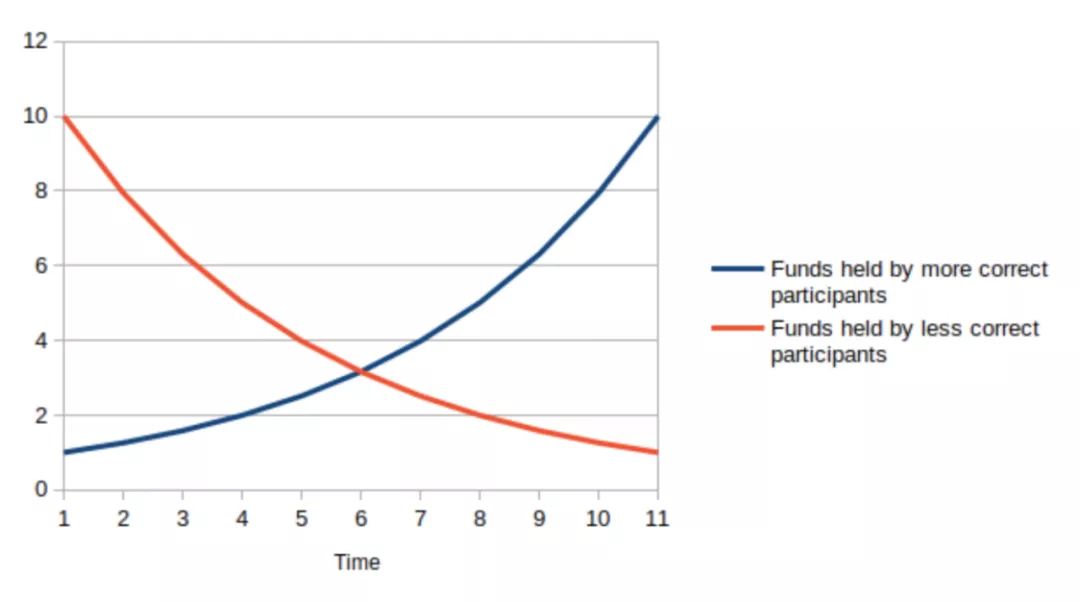

Here's what happens in the diagram:

In the Ethereum ecosystem, this difference can be shown to be insignificant; tens of millions of dollars per year is "enough" for the required R&D, and adding more money will not necessarily improve the status quo. Therefore, the risks of establishing the credible neutrality of in-protocol developer funds to the platform outweigh the benefits. But in many smaller ecosystems, including those within Ethereum and fully independent blockchains such as BCH and Zcash, the same debate is brewing, and at these smaller scales, imbalances can be very large. big difference.

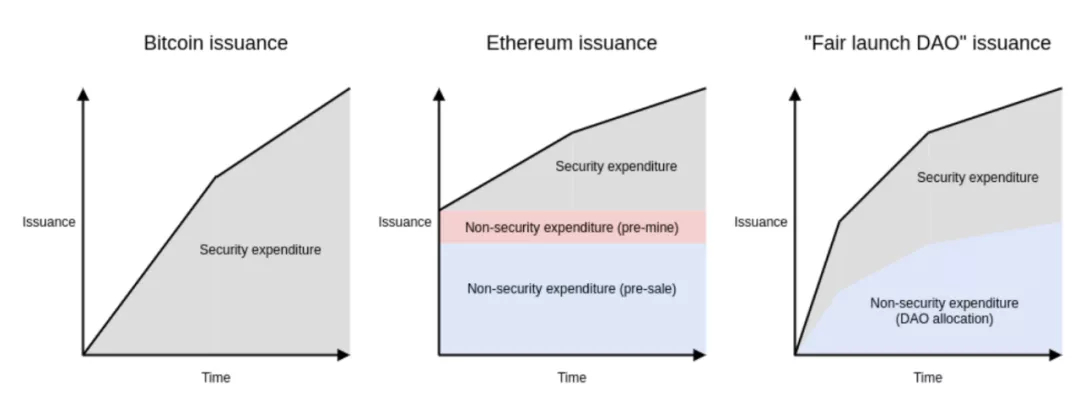

Enter DAOs. a from day one as"pure"A project launched by DAO that can realize the combination of two properties that were previously impossible to combine. (i) sufficiency of developer funding, and (ii) credible neutrality of funding (the coveted “fair launch"). Instead of funding developers from a hard-coded list of receiving addresses, decisions can be made by the DAO itself.

Of course, it's hard to make a launch perfectly fair, and the unfairness of information asymmetry is often worse than that of explicit preconditions (considering that at the end of 2010 when 1/4 of the supply had been released , so few people have had a chance to hear it, is Bitcoin really a fair launch? But even so, in-protocol compensation for non-secure public goods from day one seems to be a step toward getting enough and more A potentially significant step forward for credible neutral developer funding.

DeGov needs protocol maintenance and upgrades

In addition to public goods funding, another equally important issue requiring governance is protocol maintenance and upgrades. While I advocate minimizing all non-automated parameter tuning (see the "Limited Governance" section below) and am a fan of RAI's "non-governance" strategy, sometimes governance is unavoidable. Price oracle inputs have to come from somewhere, and sometimes somewhere needs to change. Improvements must be coordinated somehow before the agreement "zooms" into its final form. At times, the protocol's community may think they are ready to ossify, but then the world throws a curveball that requires a complete and contentious reorganization. What would happen if the dollar collapsed and RAI had to scramble to create and maintain its own decentralized CPI index to keep its stablecoin stable and relevant? Here too, DeGov is necessary, so avoiding it entirely is not a viable solution.

An important distinction is whether off-chain governance is feasible. I have long been a fan of supporting off-chain governance wherever possible. In fact, off-chain governance is absolutely possible with the underlying blockchain. But for application layer projects, especially defi projects, the problem we encounter is that application layer smart contract systems often directly control external assets, and this control cannot be forked. If Tezos' on-chain governance is captured by an attacker, the community can hard fork without any loss of (admittedly high) coordination costs. If MakerDAO's on-chain governance is captured by an attacker, the community can absolutely launch a new MakerDAO, but they will lose all ETH and other assets held in the existing MakerDAO CDP. Therefore, while off-chain governance is a good solution for base layer and some application layer projects, many application layer projects, especially DeFi, inevitably require some form of formal on-chain governance.

DeGov is dangerous

However, all current instances of decentralized governance come with significant risks. For followers of my articles, this discussion is not new; the risks are much the same as those I discuss here, here and here My concerns about token voting fall into two main categories. (i) inequality and incentive misalignment even in the absence of an attacker, and (ii) outright attack through various forms of (often vague) ticket buying. For the former, there are already a number of suggested mitigations (like authorization), and there are more to come. But the latter is the more dangerous elephant in the room and I don't see a solution in the current token voting paradigm.

Token voting is problematic even in the absence of an attacker

Even without a clear attacker, the problems of token voting are increasingly well understood (see, for example, a recent article by DappRadar and Monday Capital), and mainly fall into a few categories:

A small group of wealthy participants (“whales”) is better at successfully executing decisions than a large group of minority shareholders. This is because of the tragedy of the commons among minority shareholders: each minority shareholder has only negligible influence on the outcome, so they have no incentive to really vote without being lazy. Even with rewards for voting, there is little incentive to research and think carefully about what they are voting for.

Token voting governance empowers token holders and token holders at the expense of the rest of the community: the protocol community is made up of diverse voters with many different values, visions, and goals. However, token voting only gives power to one constituency (token holders, especially wealthy constituencies) and leads to disproportionate emphasis on the goal of increasing token prices, even if this involves harmful rent extraction.

Conflict of interest issues: Giving voting rights to a constituency (coin holders), especially the wealthy who over-delegate to that constituency, risks over-exposure to conflicts of interest of that particular elite (e.g. investing in funds or holding both Holders of tokens of other DeFi platforms that the platform interacts with).

To solve the first problem (and thus mitigate the third), one major strategy is being attempted: delegation. Minority shareholders don't have to judge every decision themselves; instead, they can delegate it to community members they trust. This is an honorable and worthwhile experiment; we'll see how well delegation alleviates the problem.

My vote delegation page in Gitcoin DAO

On the other hand, the problem of staker centricity is significantly more challenging: staker centricity is inherent in a system where staker votes are the only input. The misconception that stakeholder centralism is a desired goal, rather than a mistake, has caused confusion and harm; a (very excellent) article discussing blockchain public goods complains:

Can crypto protocols be considered public goods if ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few whales? Colloquially, these market primitives are sometimes described as “public infrastructure,” but if blockchain serves the “public” today, it is primarily a form of decentralized finance. Fundamentally, these token holders have only one common concern: price.

This complaint is misplaced; blockchain serves a richer and broader public than DeFi token holders. But our token voting-driven governance system completely fails to capture this, and it seems difficult to build a governance system that captures this richness without a more fundamental change in the paradigm.

Token Voting's Deep Essential Vulnerability to Attackers: Buying Tickets

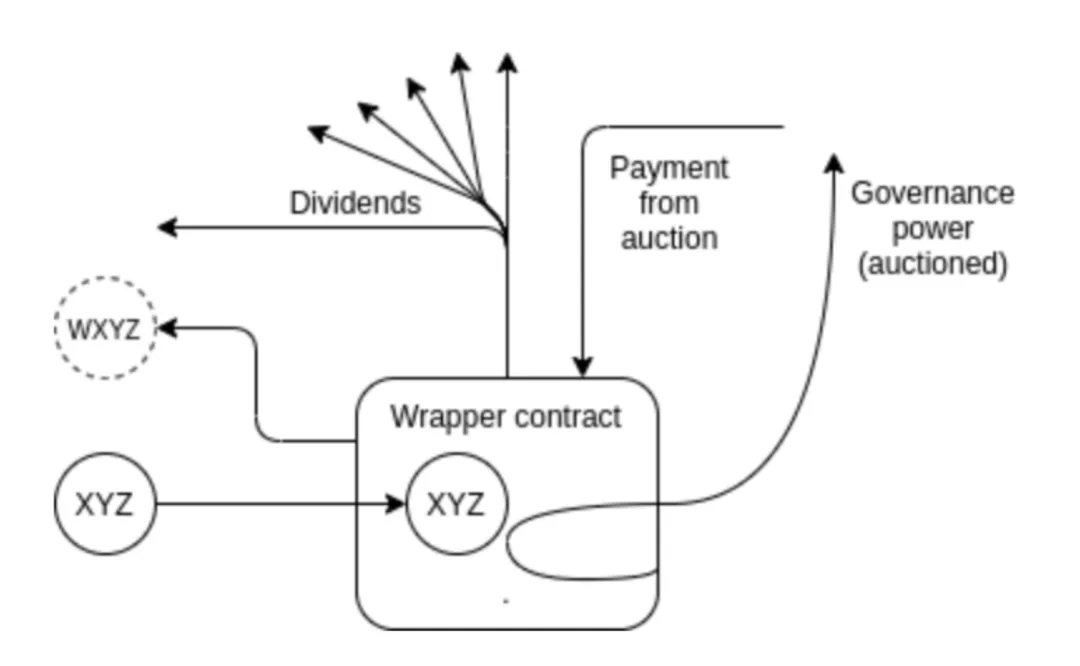

Once it is determined that an attacker trying to subvert a system enters the picture, the problem gets worse. The basic vulnerability of token voting is easy to understand. A token in a protocol with token voting is a bundle of two rights combined into a single asset: (i) some economic interest in protocol revenue and (ii) the right to participate in governance. This combination is deliberate: the goal is to align power and responsibility. But in practice, these two rights are easily separated from each other. Imagine a simple wrapper contract with these rules: If you deposit 1 XYZ into the contract, you get 1 WXYZ. WXYZ can be converted back to XYZ at any time, plus it accrues dividends. Where does the dividend come from? Well, while the XYZ tokens are in the wrapper contract, the wrapper contract is free to use them in governance (making proposals, voting on proposals, etc.). The wrapper contract simply auctions off this right on a daily basis and distributes the profits to the original depositors.

As an XYZ holder, is it in your interest to deposit your tokens into the contract? If you're a very large holder, it probably isn't; you like dividends, but you fear what a misplaced actor might do with the governance power you're selling. But if you're a smaller holder, it's a great fit. If the governance rights of the wrapper contract auction are bought by an attacker, you will personally only suffer a fraction of the cost of bad governance decisions made by your token, but you will personally receive the full benefit of the dividend governance auction. The situation is a classic tragedy of the commons.

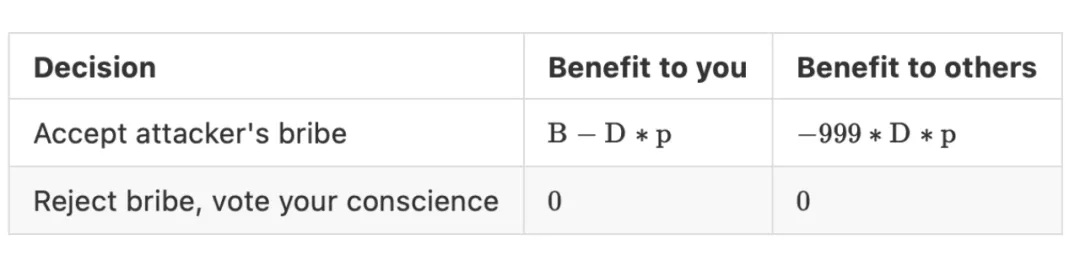

Suppose an attacker makes a decision that breaks the DAO, thus benefiting the attacker. What is the harm of decision success to each participant? What is the probability of a single vote skewing the outcome? Suppose the attacker is bribed? The game graph looks like this:

Decisions are good for you and good for others

accept bribes from attackers

Say no to bribes, vote for your conscience

If , you tend to accept bribes, but as long as , accepting bribes is harmful to the collective. Thus, if (usually much lower than ), the attacker has the opportunity to bribe users into taking net negative decisions, compensating each user much less than the harm they suffer.

A natural critique of the fear of voter bribery is: would voters really be so immoral as to accept such an obvious bribe? The average DAO token holder is a fanatic, and it is difficult for them to be satisfied with such a selfish and blatant sale of the project. But that misses the point that there are more confusing ways to separate profit-sharing rights from governance rights that don't require something as explicit as an encapsulation contract.

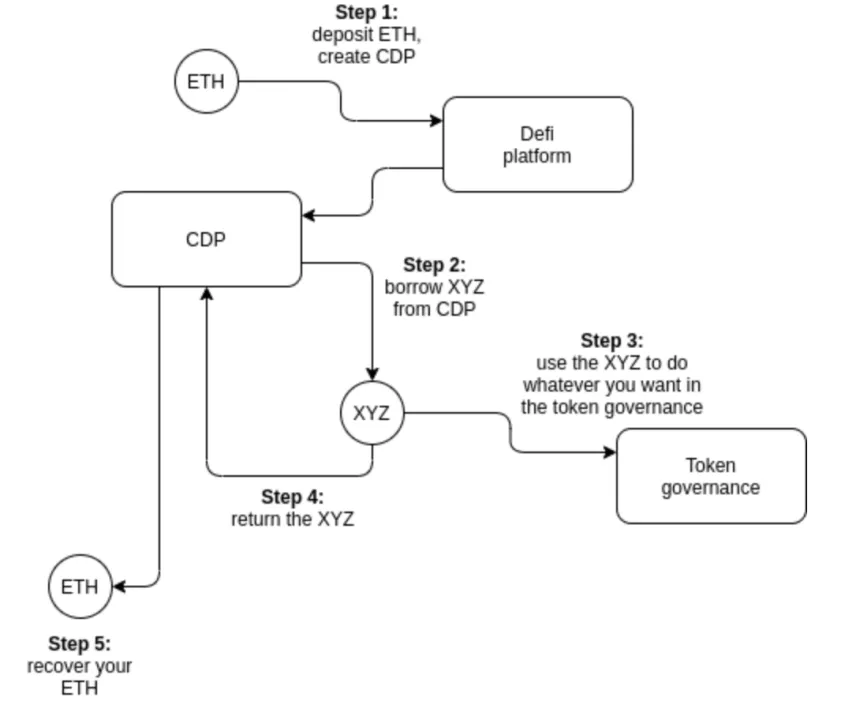

The simplest example is borrowing from a defi lending platform such as Compound. People who already hold ETH can lock their ETH in a CDP (“Collateralized Debt Position”) on one of these platforms, and once they do so, the CDP contract allows them to borrow a certain amount of XYZ, for example. Half the value of the ETH they put in. Then they can do whatever they want with this XYZ. In order to get their ETH back, they will eventually need to pay back the XYZ they borrowed plus interest.

Note that the borrower has no financial risk to XYZ throughout the process. That is, if they use their XYZ to vote for a governance decision that destroys the value of XYZ, they don't lose a penny. What they hold in XYZ is XYZ, which they eventually have to pay back to the CDP anyway, so they don't care if its value goes up or down. So we achieved unbundling: Borrowers have governance rights but no economic interest, and lenders have economic interest but no governance rights. Some DAO protocols are using techniques like timelocks to limit people's ability to participate in such attacks, but ultimately timelocks are bypassable; in terms of security systems, timelocks are more like a paywall on a newspaper website, Instead of lock and key.

There are also centralized mechanisms that separate profit-sharing rights from governance rights. Most notably, when users deposit their tokens into a (centralized) exchange, the exchange holds full custody of those tokens, and the exchange has the ability to vote with those tokens. This is not pure theory; there is evidence that exchanges use their users' tokens in several DPoS systems. The most obvious recent example is the hostile takeover attempt of Steem, where exchanges used their customers’ tokens to vote for some proposals that would help solidify the acquisition of the Steem network, while the majority of the community strongly opposed it. The situation was only resolved by a complete mass exodus, with most of the community moving to another chain called Hive.

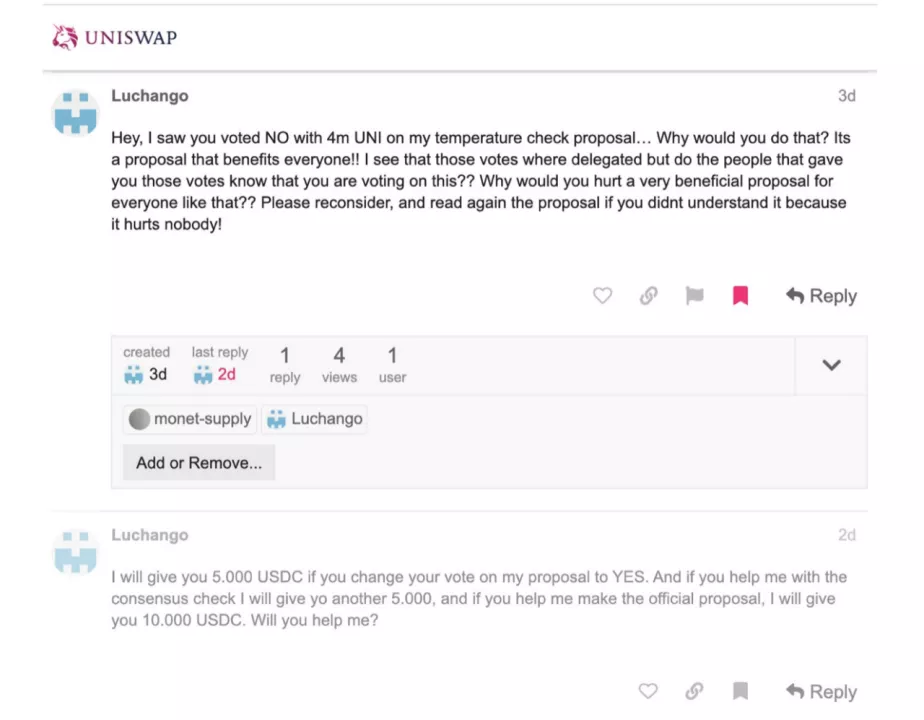

Currently, many token-voting blockchains and DAOs have managed to avoid these worst forms of attacks. Occasionally there were signs of attempted bribery.

But despite all these important problems, simple economic reasoning suggests far fewer examples of direct voter bribery, including in obscure forms such as exploiting financial markets. The question to ask is: Why haven't more direct attacks happened yet?

My answer is,"Why not yet" relies on three chance factors that are true today but may become less and less true over time.

Community spirit comes from having a tight-knit community where everyone feels camaraderie in a shared tribe and mission.

The wealth of token holders is highly concentrated and coordinated; large holders have a higher ability to influence outcomes and are invested in long-term relationships with each other (both the "old boys club" of VCs and many others as well). powerful but low profile group of wealthy token holders), and this makes them harder to bribe.

The financial market for governance tokens is immature: off-the-shelf tools for making wrapped tokens exist in proof-of-concept but not widely used, bribery contracts exist but are equally immature, and the lending market is illiquid.

secondary title

Solution 1: Limited Governance

One possible mitigation to the above problems, and one that has been tried to varying degrees, is to place limits on what token-driven governance can do. There are several ways to do this.

Use on-chain governance for applications only, not the base layer: Ethereum already does this because the protocol itself is governed via off-chain governance, and DAOs and other applications on top of that sometimes (but not always) Yes) Governance through on-chain governance - on-chain governance.

Limit governance to fixed parameter choices: Uniswap does this because it only allows governance to influence (i) token distribution and (ii) 0.05% fees on Uniswap exchanges. Another good example is RAI's "non-governance" roadmap, where governance has control over fewer and fewer features over time.

Added time delay: Governance decisions made at time T only take effect at e.g. T + 90 days. This allows users and applications that find the decision unacceptable to move to another application (possibly a fork). Compound has a time delay mechanism in its governance, but in principle, the delay could (and ultimately should) be longer.

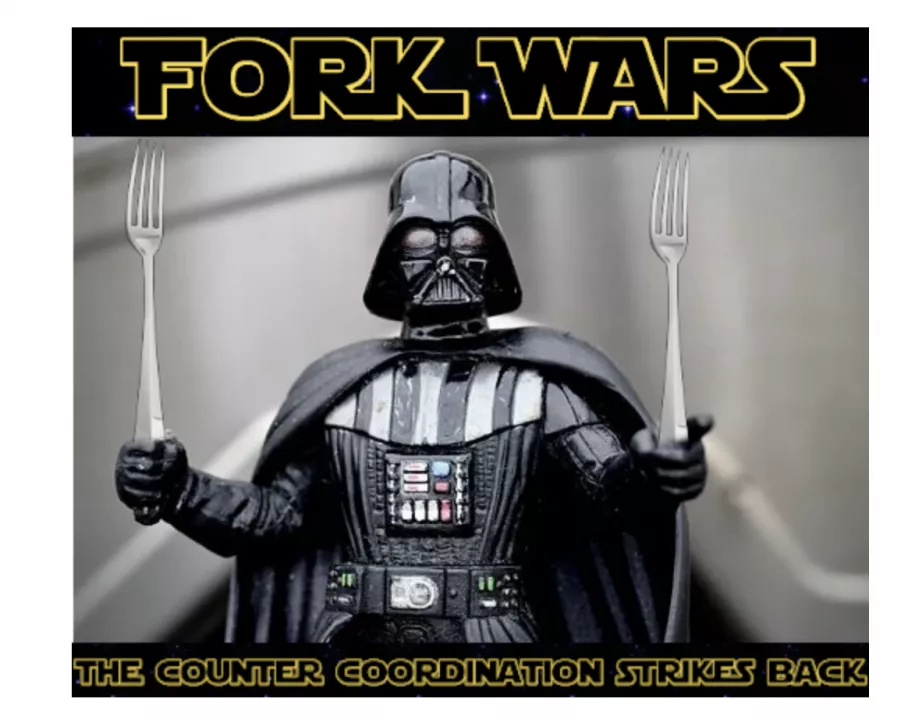

More friendly to forks: Make it easier for users to quickly coordinate and execute forks. This makes capturing governance less rewarding.

The Uniswap case is particularly interesting: this is an expected behavior, with on-chain governance funding teams that may develop future versions of the Uniswap protocol, but it is up to users to choose to upgrade to those versions. This is a hybrid of on-chain and off-chain governance, leaving only a limited role for the on-chain party.

secondary title

Solution 2: Non-Token-Driven Governance

The second approach is to use non-token voting driven forms of governance. But if tokens don't determine an account's weight in governance, what is? There are two natural options:

Proof-of-personality system: A system that verifies that accounts correspond to unique individuals so that governance can assign each individual a vote. Check here for a review of some of the technologies being developed, as well as two attempts by Proof Of Humanity and BrightID to make this happen.

Proof of Participation: A system that proves the fact that certain accounts correspond to people who participated in certain activities, passed certain educational training, or performed some useful work in the ecosystem. See POAP for how to do this.

There is also the possibility of mixing: one example is quadratic voting, which makes the power of individual voters proportional to the square root of their committed economic resources. Preventing people from gaming the system by allocating their resources to multiple identities requires proving a person's identity while still having a financial component that allows participants to credibly show how much they care about an issue and how much they care about the ecosystem degree. Gitcoin quadratic funding is a form of quadratic voting, and a quadratic voting DAO is being built.

Proof of participation is less well known. The key challenge is that determining the level of participation itself requires very strong governance structures. The simplest solution might be to bootstrap the system with a handpicked group of 10-100 early contributors, then gradually evolve over time as selected participants in round N determine the participation criteria for round N+1. centralized. The possibility of a fork helps provide a path to recovery from governance derailments and provides an incentive.

secondary title

Solution 3: Asymmetric Trap

A third way is to break the tragedy of the commons by changing the rules of voting itself. Token voting fails because while voters are collectively responsible for their decisions (if everyone votes for a bad decision, everyone's tokens go down to zero), each voter No personal responsibility (if a bad decision happens, those who supported it will suffer no more than those who opposed it). Can we make a voting system that changes this dynamic and makes voters individually, not just collectively, accountable for their decisions?

If the fork is done the way Hive forked from Steem, fork-friendliness could be a game tactic. If a disruptive governance decision succeeds and there is no longer opposition within the protocol, users can fork at their own discretion. Also, in that fork, tokens that voted for a wrong decision could be destroyed.

This sounds harsh, and might even feel like a violation of an implicit norm that “ledger immutability” should remain sacrosanct when forking tokens. But from one perspective, the idea seems more plausible.

We maintain the idea of a strong firewall where individual token balances are not expected to be violated, but apply this protection only to tokens that do not participate in governance. If you participate in governance, even indirectly by putting your tokens into a wrapping mechanism, then you may be liable for the cost of your actions.

secondary title

Asymmetric Risks in Everyday Voting

But the above only works to prevent really extreme decisions. What about petty robberies? Unfairly favoring attackers to manipulate the economics of governance, but not bad enough to cause devastating damage? What about simple laziness, and the fact that token voting governance has no selection pressure in favor of higher quality opinions in the absence of any attackers at all?

The most popular solution to this type of problem is futarchy, introduced by Robin Hanson in the early 2000s. Voting becomes a bet: by voting yes, you are betting that the proposal will lead to a good outcome, and by voting against the proposal, you are betting that the proposal will lead to a bad outcome. The reason for Futarchy introducing personal liability is obvious: if you bet well, you get more tokens, and if you bet badly, you lose your tokens.

"Pure" futarchy has proven difficult to introduce because in practice the objective function is hard to define (people want more than token prices!), but various hybrid forms of futarchy can be quite effective. Examples of hybrid futarchy include:

Voting as a buy order: see ethresear.ch post. Voting for a proposal requires creating an executable buy order to purchase additional tokens at a price slightly lower than the current price of the token. This ensures that if a bad decision works out, those who backed it may be forced to buy out their opponent, but it also ensures that in more "normal" decisions, token holders would More decisions can be made based on non-price criteria.

Retroactive Public Goods Funding: See this post from the Optimism team. Public goods are retroactively funded by some voting mechanism after outcomes have already been achieved. Users can purchase project tokens to fund their project while demonstrating confidence in it; if the project is deemed to have achieved the desired goals, purchasers of project tokens will receive a reward.

Level up game: see Augur and Kleros. The value alignment of lower-level decisions is incentivized by the possibility of attracting higher-effort but more accurate higher-level processes; voters who vote for final decisions are rewarded.

secondary title

hybrid solution

There are also solutions that combine elements of the above technologies. Some possible examples:

Time Delay Plus Elected Expert Governance: This is a possible solution to the age-old conundrum of how to make a crypto-collateralized stablecoin whose funds locked up can exceed the value of the token in profit, without governance capturing risk. Stablecoins use a price oracle that is the median of values submitted by n (eg, n = 13) selected providers. The token votes for suppliers, but it can only cycle out one supplier per week. If a user notices that token voting leads to an untrustworthy price provider, they have N/2 weeks to switch to another stablecoin before the stablecoin breaks.

Futarchy + Anti-collusion = Reputation: Users vote in "Reputation", a non-transferable token. Users gain more reputation if their decisions lead to desired outcomes, and lose reputation if their decisions lead to undesired outcomes. See here for an article advocating reputation-based programs.

Loosely coupled (consultation) token voting: Token voting does not directly implement the proposed change, but only to publicize its results, establishing legitimacy for off-chain governance to implement the change.

This can provide the benefits of token voting while mitigating the risks, as the legitimacy of token voting is automatically reduced if there is evidence that token voting has been bribed or otherwise manipulated.

But these are just a few possible examples. There is still a lot of work to be done in researching and developing non-token-driven governance algorithms. The most important thing that can be done today is to move away from the idea that token voting is the only legitimate form of decentralized governance. Token voting is attractive because it feels neutral: anyone can earn some units of the governance token on Uniswap. In practice, however, token voting may only look safe today because of its flawed neutrality (i.e., the majority of the supply is in the hands of a small, tightly-coordinated group of insiders).

We should be wary of the idea that the current form of token voting is a "safe default". Much remains to be seen about how they will function under conditions of greater economic stress and maturing ecosystems and financial markets, and now is the time to start experimenting with alternatives in parallel.