誰在預測市場反常識下注?

- 核心觀點:預測市場「反常識」合約流動性由三類理性策略提供。

- 關鍵要素:

- 彩票人:以小博大,追逐高賠率黑天鵝事件。

- 機器人:自動化交易,通過價差和刷量策略獲利。

- 預測平台:通過掛單和持倉獎勵激勵流動性。

- 市場影響:揭示預測市場深層流動性來源與博弈邏輯。

- 時效性標註:長期影響。

Original | Odaily (@OdailyChina)

Author|Golem (@web3_golem)

This week, I wrote an article reviewing absurd event contracts on Polymarket, pointing out that betting on some seemingly utterly ridiculous contracts at this moment could be profitable.

This led me to ponder: who exactly is going against "common sense" to provide "free money" for the market?

Bets opposing smart players like us aren't completely impossible; there are certainly some people who firmly believe in their judgment (for example, some still believe the Earth is flat). However, prediction markets are not a "greater fool market." I believe when players use real money to predict whether an event will occur, they will try their best to think as "rational actors," meaning their decisions are the most economical and profitable. Therefore, from this perspective, users betting "Yes" on seemingly impossible event contracts must also have some profit-making strategy; they aren't fools providing us with "high-certainty" investment opportunities for free.

After consideration and discussion, I believe those providing counterparty liquidity in these absurd event markets likely fall into the following three categories (this article aims to stimulate discussion; feedback and corrections are welcome, X @web3_golem):

Lottery Players

The logic of lottery players is simple: they focus solely on odds, aiming for a small stake to win big.

Sometimes, reality is far more bizarre than we imagine; even seemingly outrageous events can happen. Moreover, while prediction markets settle based on real-world outcomes, settlement results can sometimes be distorted due to settlement conditions, system failures, etc. Polymarket has had multiple instances where settlement results diverged from reality due to issues with UMA's dispute resolution mechanism. A recent example is Polymarket ruling that the US military operation in Venezuela did not constitute an "invasion."

Thus, long-tail odds discrepancies emerge. Even for extremely low-probability events, the "Yes" side might still have a 1%-3% price. As long as the odds are sufficiently high, "lottery players" will buy, becoming one of the firm bottom bids.

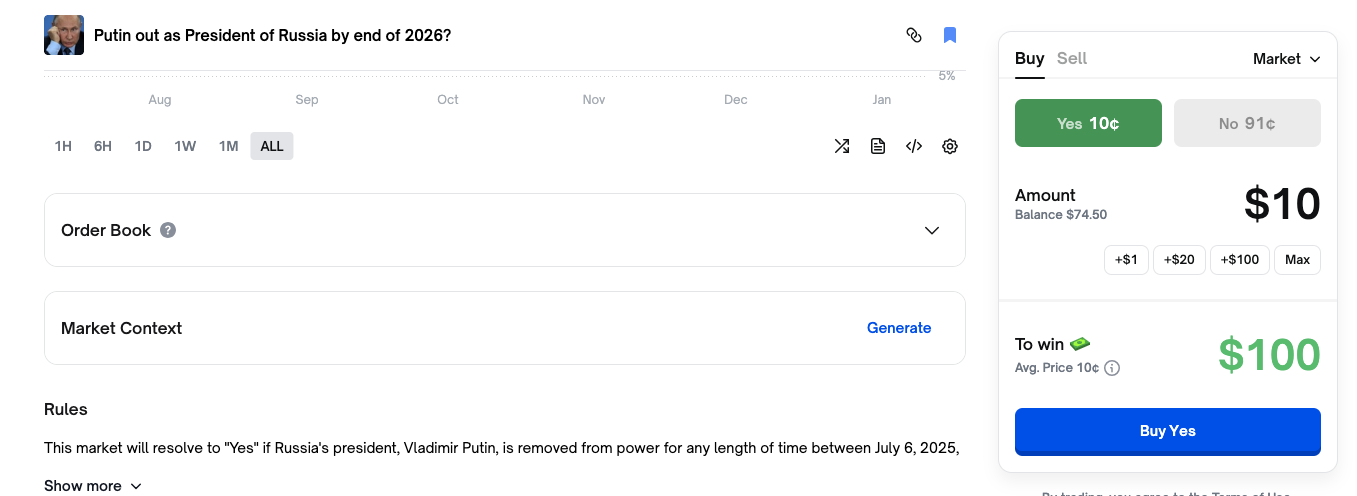

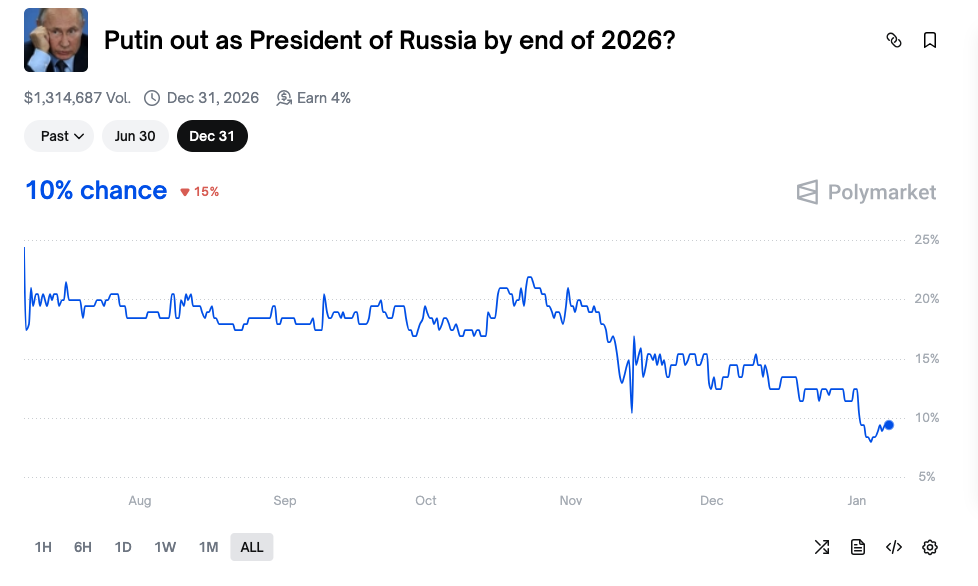

But actually, this "lottery player" psychology is also rational. For example, in the contract for "Will Putin step down before the end of 2026?", driven by common sense, most people would buy "No," and the probability already reflects people's attitude. However, the "Yes" side still has a 10% probability. This means if you bet $10 and Putin actually steps down before the end of 2026, you would get a $100 return—a 10x gain. So why not gamble?

Furthermore, lottery players don't necessarily place heavy bets on a single market. Since prediction markets are不缺 such high-odds events, by casting a wide net and hitting the jackpot a few times, there's still a chance to recoup costs or even profit.

They anticipate black swan events more than normal people. Therefore, they are happy to provide buy-side liquidity on the "Yes" side of "counter-common-sense" markets (Polymarket sometimes offers maker rewards and holding rewards in certain markets, but this is not the main driver for lottery players).

Bots

If an event contract itself has high certainty, the entry of tail-end players' funds can push one side's probability to 99%-100% before settlement. The existence of "lottery players" can partly explain why there are still players taking the "Yes" sell orders in these "counter-common-sense" markets (Odaily note: Because Polymarket uses a shared order book, meaning when the "No" side has a buy order for $0.99, a corresponding sell order for $0.01 will appear on the "Yes" side). However, they are always a minority and cannot explain why these markets still have large trading volumes and good depth.

So, who else injects substantial liquidity into these markets? The answer is bots.

Market-making bots on Polymarket have developed quite rapidly. Bots using the Polymarket API for automated trading actively monitor all newly created markets and are often among the first participants. These bots can profit by actively trading in these markets.

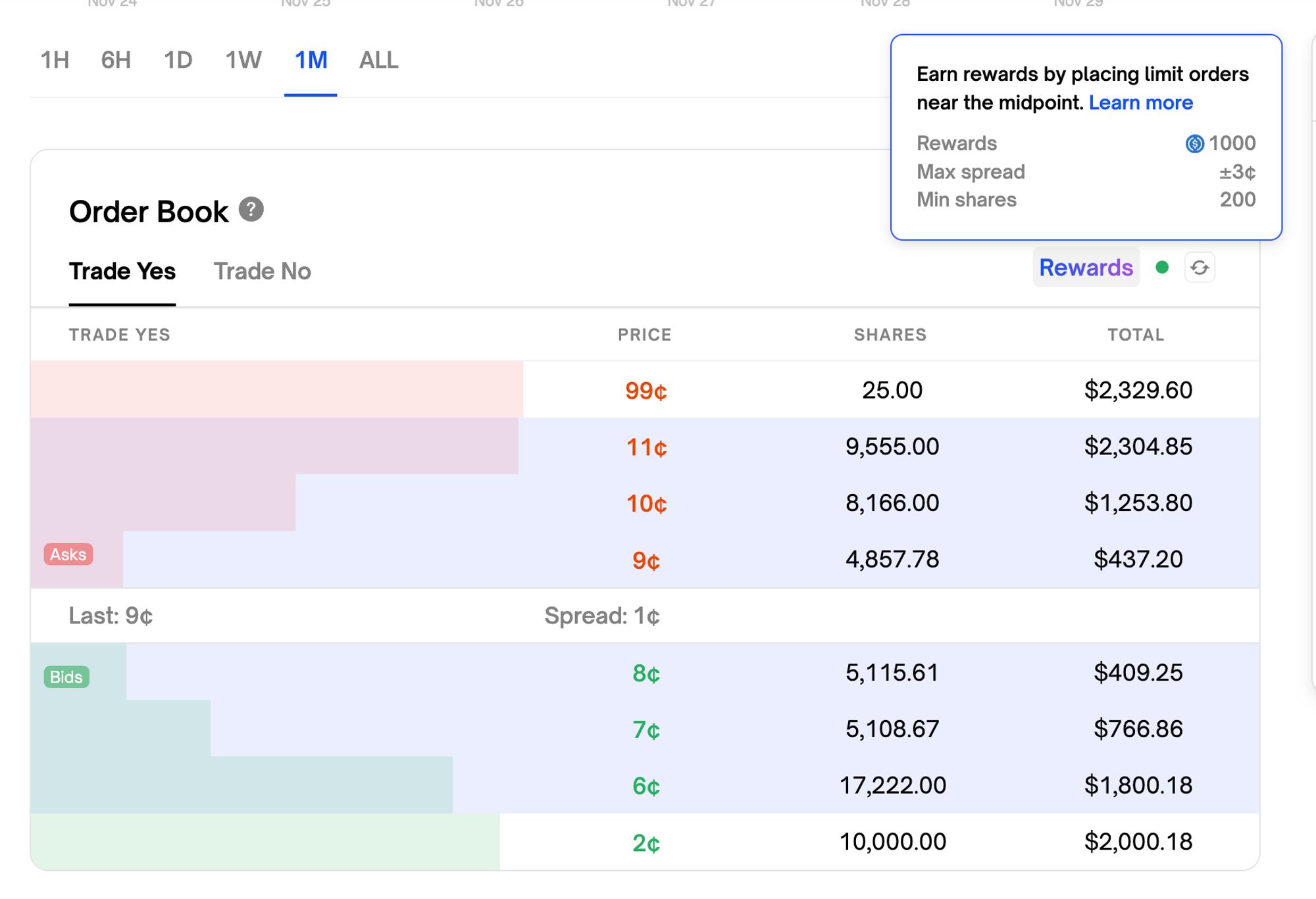

In these "counter-common-sense" markets, when the "No" side price is $0.99, due to the shared order book, sell orders for $0.01 will appear on the "Yes" side. Market-making bots, like "lottery players," will take these $0.01 sell orders. But immediately after, they will place sell orders on the "Yes" side at $0.02, $0.03, or even higher, waiting for "lottery players" or other bots to fill them. Buy orders for $0.98, $0.97, or even lower will also appear on the "No" side (Odaily note: again due to the shared order book). Thus, the order book gains significant depth.

However, after communicating with the team from crypto VC Jsquare (they invested in prediction market aggregator Rocket), they believe there aren't many bots executing this specific strategy in the market. In these "counter-common-sense" markets, the speculative psychology of "lottery players" or regular players is enough to support most of the opposing bets.

The existence of some wash-trading bots also provides market liquidity and trading volume for these "counter-common-sense" and somewhat niche markets (compared to events like the US election). One wash-trading bot places a buy order for $0.02 on the "Yes" side, and another wash-trading bot places a buy order for $0.98 on the "No" side to match it.

This behavior is mainly to farm potential future prediction market airdrops. In high-frequency markets, orders might be matched by other players, so these "counter-common-sense" event contracts are ideal tools for wash trading.

Prediction Platforms

Besides the aforementioned "lottery players" and bots, prediction platforms themselves also contribute significantly to the liquidity of these markets.

Polymarket's mechanism includes two liquidity incentive measures: maker rewards and holding rewards. Maker rewards mean that in some specific markets, players can earn rewards simply by placing orders within the maximum specified spread. Holding rewards mean that in some specific markets, players holding shares (either Yes or No) can receive a 4% annualized holding reward.

The highlighted area indicates the maximum spread range for maker rewards.

According to statistics, Polymarket has invested approximately $10 million in market maker incentives. At its peak, it paid over $50,000 daily to maintain order book liquidity. Now, these incentives have decreased to just $0.025 per $100 traded.

These investments have indeed been effective, driving trading in many "counter-common-sense" markets. For example, the contract for "Will Putin step down before the end of 2026?" has already seen over $1.3 million in trading volume. Holding shares in this contract yields a 4% annualized reward. For players holding "Yes" shares, this effectively translates to a 14% annualized return (10% tail-end profit + 4% platform reward), which is highly attractive. For players holding "No" shares, the maker rewards and holding rewards also hedge some of the risk.

There is also speculation that, besides openly providing liquidity incentives, prediction platforms themselves act as market makers, providing liquidity for these "counter-common-sense," niche markets to achieve advertising and marketing effects. But this is purely speculative and open for discussion.