Author: CONCODA

Original compilation: Block unicorn

The banking panic is nearing its end, but the Fed has returned to tightening policy, which will not only lead to the inevitable bankruptcy and subsequent bailout, but will also strengthen the global influence of the US central bank, and the Fed will soon act to tighten the financial system. policy.

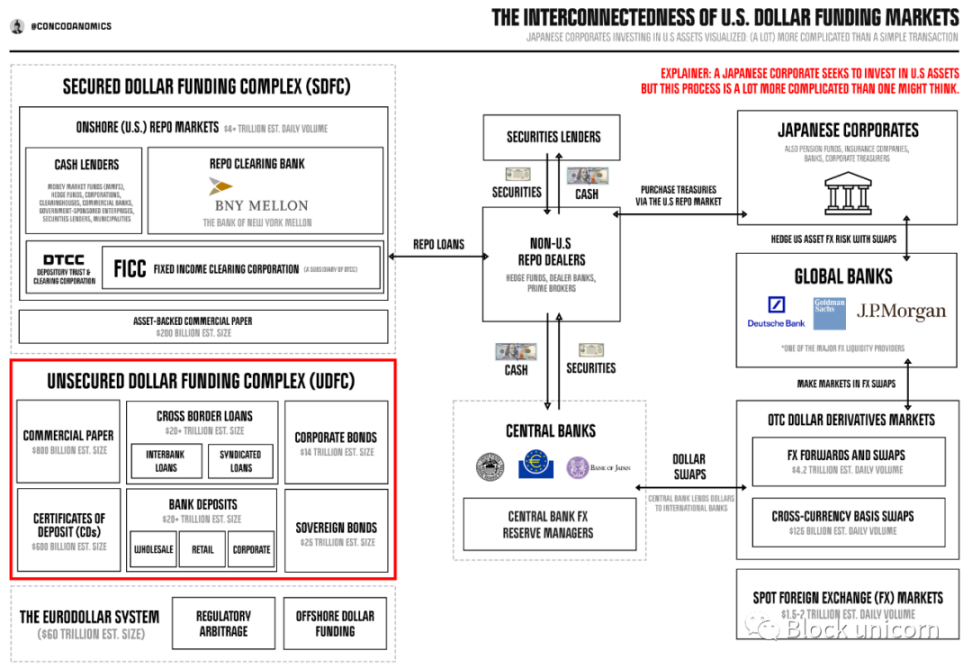

The global financial crisis of 2007/08 changed the global monetary system forever. Monetary leaders and financial titans have shaped a new paradigm that the American empire will absorb any systemic risk, especially if it threatens the status quo. The bank bailout marks a shift from "unsecured" to "secured" monetary standards. The powerful unsecured dollar financing system (UDFC), in which banks and global corporations finance their operations by borrowing from each other, is about to lose its supremacy.

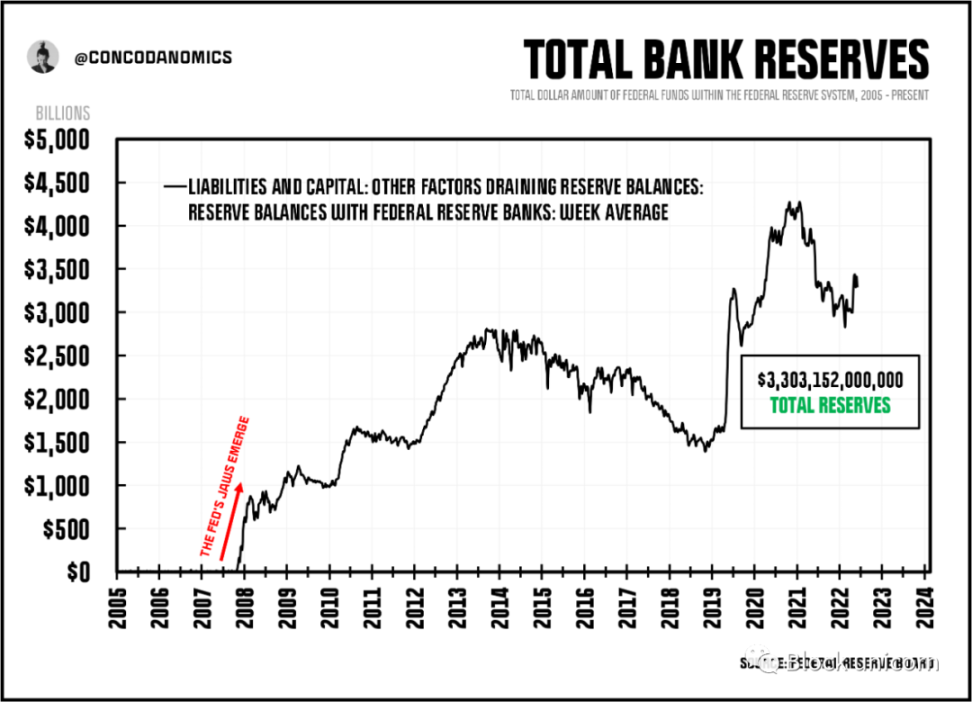

After a massive restart of the global financial machine by the Federal Reserve, the unsecured dollar funding system was doomed. By injecting trillions of dollars into the interbank system in "bank reserves," the currency that banks use only to settle payments, central bankers have led to the beginning of the era of "excess reserves" in financial markets.

As more and more reserves were poured into the financial system, the secured dollar funding system (SDFC) gradually replaced the unsecured dollar funding system (UDFC). The regulator's decision to require banks to stop relying on each other for funding means taking loans from shadow banks in the repo market while attracting more retail deposits - the cheapest and most regulatory-compliant source of funding.

The co-financing boom among the big banks is over as the Fed keeps pumping more reserves into the system. Gone are the days when a big bank like JPMorgan would borrow federal funds (interbank reserves) from smaller regional banks to cover a funding shortfall. The Fed pumped trillions of dollars in reserves into the system through QE (quantitative easing) asset swaps with major dealers, but Wall Street banks were the biggest beneficiaries. The most systemic entities in the global financial system will no longer experience major liquidity problems. At least in theory. In effect, the Fed has switched from a rather unstable system to a fairly stable successor.

The old "federal funds corridor" (the monetary policy framework the Fed used before 2007) system of setting interest rates by adding or subtracting settlement balances by flooding the system with reserves has broken down. Instead, the Fed has implemented a "Fed via massive injection of bank reserves" system, in which officials influence interest rates within a range of targets they deem appropriate. Meanwhile, the monetary architects of the BIS (the Bank that calls itself the Central Bank) decided to try and completely dispel the notion of a big bank collapse, and their solution was to turn reserves into the main safety mechanism of the financial system.

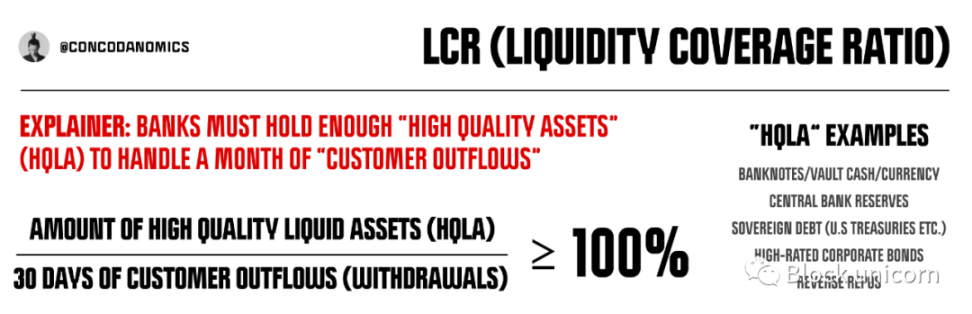

Through years of trial and error, global regulators have transformed most financial institutions, primarily central banks, from prudent speculators into currency bastions by implementing the Basel framework. However, they pay a price for security. Regulatory ratios, namely Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), etc., limit the ability of banks to engage in anything other than tedious financial activities. Not only is exotic trading in the foreign exchange market eliminated, even servicing the financial markets has become challenging.

The first is the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), designed in December 2010 and fully endorsed by regulators in early 2013. This regulation limits the ability of banks to increase the size (and therefore leverage) of their balance sheets by forcing them to raise corresponding equity capital (i.e. retained earnings and common shares). But that's not all. In addition, banks must hold sufficient “HQLA” high-quality asset portfolios at all times, mainly composed of bank reserves and US Treasury bonds, and a certain proportion of other “safe assets”. According to the methodology provided by the Basel Committee, banks need to hold more high-quality assets (HQLA) than the 30 days of customer outflow funds. This complex calculation will vary from bank to bank, but can be simplified into an easy-to-understand score.

The regulator further encouraged banks to cap the LCR at 100%, seeing 125% as an adequate buffer against any systemic catastrophe. Most financial institutions followed this rule, and most banks increased their LCR to 125% and kept it unchanged, such as JPMorgan Chase.

But the central planners were not satisfied. In addition to the LCR, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) further constrains a bank's risk tolerance. Before the outbreak of the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, banks failed to adequately estimate, manage and control their liquidity risks. NSFR aims to enhance banks' ability to meet liquidity outflows for a longer period of time. This means that more "stable funds" need to be held to deal with the liquidity outflow of "stable assets".

To improve banks' liquidity, not just short-term but long-term, currency leaders hope to increase Bank liquidity. Used in conjunction with other regulations, NSFR forces banks to reduce liquidity risk by replacing "more drainable" deposits (such as deposits from institutional investors) with more retail deposits and long-term debt, and these forms of funding were the architects of NSFR It is believed that the most able to resist the liquidity crisis.

Even so, regulators believe there is one institutional weakness that must be addressed. During the subprime boom, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) were considered so safe that banks could not imagine them becoming worthless. In addition, the banks believe they have taken "risk-free" credit default swaps (CDS) against their MBS positions. However, the market believes that both CDS and MBS are worthless.

In order to prevent the recurrence of events similar to the subprime mortgage crisis, regulators created the SLR (Additional Leverage Ratio), the most stringent regulatory ratio. SLR's belief that all assets, even U.S. Treasuries and reserves (considered the most liquid and safest assets in the world), can be problematic was ultimately confirmed when the COVID-19 market crashed. The more systemically important you are, the more capital you need to hold to deal with your balance sheet leverage. But the SLR also goes a step further by stating that reserves and US Treasuries are as encumbered as mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps.

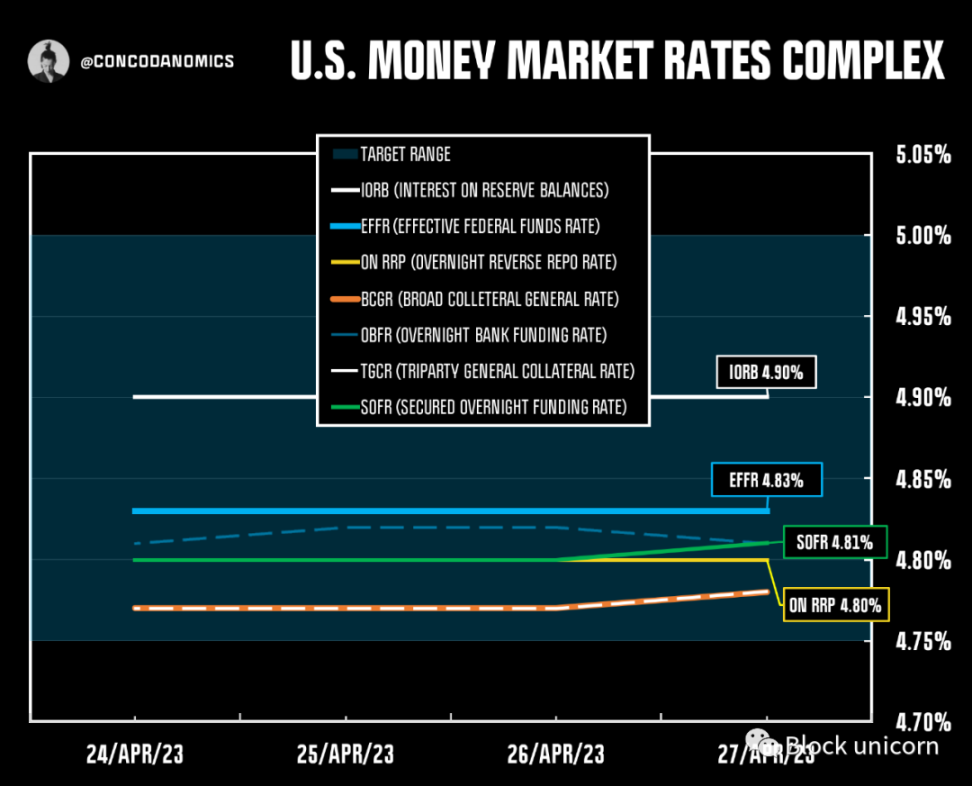

The ultimate goal of the regulation of the Basel Rules is to establish a global financial system centered on the holding of reserves. The LCR/NSFR standard combined with the trillions in reserves being pumped into the system by the Fed and other central banks makes the concept of "excess reserves" moot. As a result, large financial institutions have gradually adapted to this "substantial reserve" system over the past decade. Since central bankers could no longer control interest rates by adding or subtracting a small percentage of reserves, they tried a new technique. Through various monetary magic tricks, the Federal Reserve attempts to control many money market interest rates, including shadow interest rates, such as those in the repo market, to achieve its policy goals. This is known as the rise of the Jaws of the Fed™.

Block unicorn note: "Jaws of the Fed™" is a term that refers to the Federal Reserve's attempt to control interest rates in various money markets, including the repo market, through the use of various monetary tools and techniques. to achieve its monetary policy objectives.

U.S. money market interest rate system

In the new system, many of the Fed's flaws quickly became apparent. Whenever the U.S. Treasury "prints money," interest rates on Treasury bonds fall below the lower end of the target range. Fast forward to September 2019, and both the federal funds rate (the Fed's benchmark rate) and repo market rates breached the upper end of their target ranges. The Fed was relying on its lead bank, JP Morgan, to reset interest rates. Since the superbank has the most reserves after endless quantitative easing injections, it should be the Fed's last line of defense.

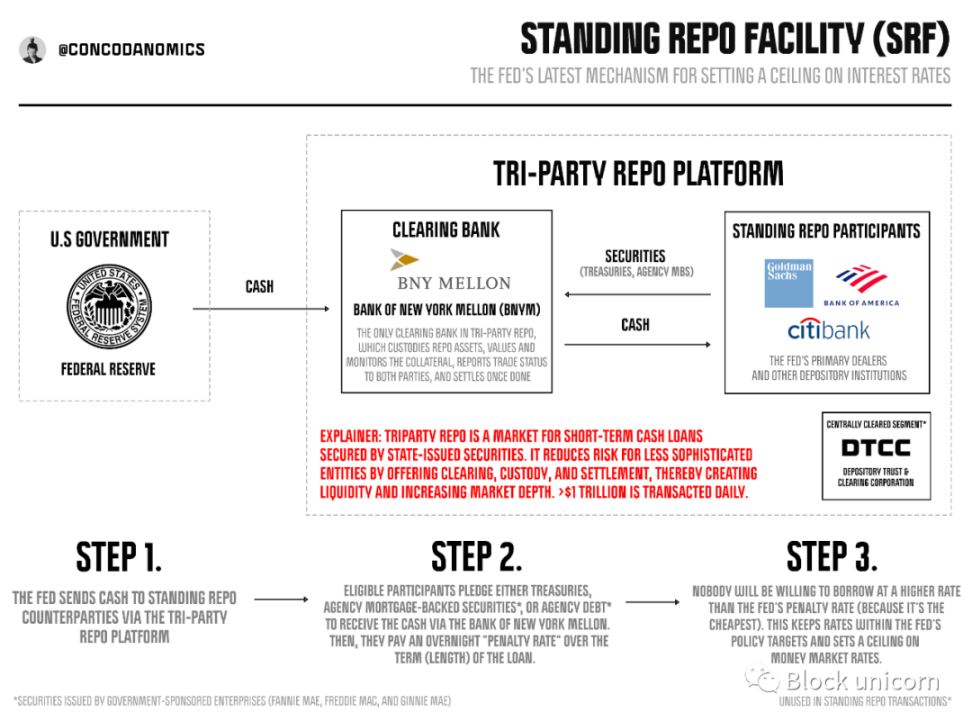

In this case, the Wall Street titans never met their obligations. The failure of the Fed's penultimate lender of last resort (JP Morgan) to step in led monetary officials to provide emergency cash through another Fed creation, the Standing Repo Facility (SRF). This puts a hard cap on borrowing costs for all market participants, since no one will borrow at a higher rate than the Fed rate. This creates what is known as the “Jaws of the Fed™.”

Finally, after numerous interventions and monetary operations, the Federal Reserve has imposed a hard cap on its local interest rate regime. Tools like the Fed's discount window and SRF provide unlimited dollars for a fee. But the Fed's mission is far from over. In the U.S.-dominated system, the Fed's grip is not only local, but global.

The meaning of this sentence is that the currency swap line opened by the Fed is its real mandible. The Fed opened up a currency swap line to provide the world with unlimited emergency dollar funding. Until last month's mini-bank panic, the world had forgotten that the Fed had opened dollar swap lines in both 2008 and 2020 to rescue nearly all sources of dollar funding, primarily the Eurodollar market.

Global dollar injection is the solution to the global financial crisis

"Jaws of the Fed" means that the Federal Reserve uses various monetary policy tools, especially interest rates and asset purchases, to influence the range of market interest rates, so as to achieve the purpose of macroeconomic regulation. The word "Jaws" comes from the movie "Jaws", which means that the market interest rate range is constantly opening and closing like a shark's jaw, which is controlled by the Federal Reserve.

In early March of this year, the Federal Reserve's global mandible (tightening interest rates, because the mandible can bite objects tightly, and the mandible can loosen the mouth to release liquidity) came into play again, curbing the spread of global contagion and maintaining the status quo of the dollar, which Reminds the world of the Fed's global presence.

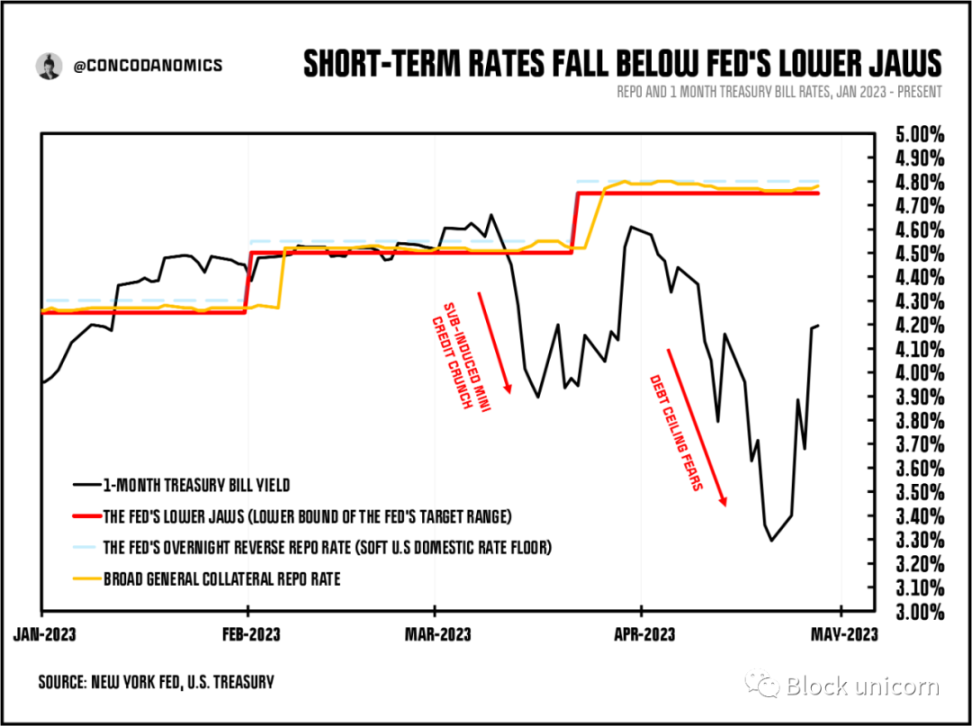

This credit crunch should have sparked discussion about the Fed's remaining woes. The Fed's upper jaw is still solid and reliable, but the lower jaw has a Death Star-like vulnerability that will eventually need to be addressed, and the global interest rate system that the Fed has established still has holes.

For the most part, the Fed has ample tools to address the leaky jaw and can push rates back into its target range by issuing large amounts of U.S. Treasuries, making "technical adjustments," or changing restrictions on and access to certain facilities.

The recent plunge in short-term Treasury yields has sparked rumors of a "collateral shortage," and some money market rates have fallen below the Fed's reverse repurchase rate (RRP), and even down to the Fed's lower limit, which is set by the Fed. lower bound on the interest rate. This shows that the Fed still has a weak link in the lower bound of interest rates globally, and not everyone who uses dollars can get the support provided by the Fed, so the lower bound of interest rates in dollars does not exist globally, but this situation is about to change .

Even so, this is not the catalyst for the Fed to address its floor. Whenever a "debt ceiling apocalypse" hits, a breach of the Fed's target range tends to follow, and monetary leaders have anticipated this. Instead, another trigger might prompt them to take action. However, the events that will force the Fed to establish a firm floor on global dollar interest rates remain unclear. But with the Fed's other flaws pushed to the point where officials have to step in, a global "hard floor" seems inevitable.

At some stage, likely when Fed tightening triggers an even worse credit crunch, monetary leaders will choose to patch the holes in their global financial systems once and for all. The Fed will open access and provide liquidity to anyone, especially those who pose a risk to the status quo. Foreign entities will gain access to U.S. dollar liquidity facilities at Fed-approved rates, and only then will the Fed's financial system be intact. The more important question now is what prompted the Fed to act like this.