Original author: a16z

Original compilation: RR,

Original compilation: RR,old yuppie

old yuppie

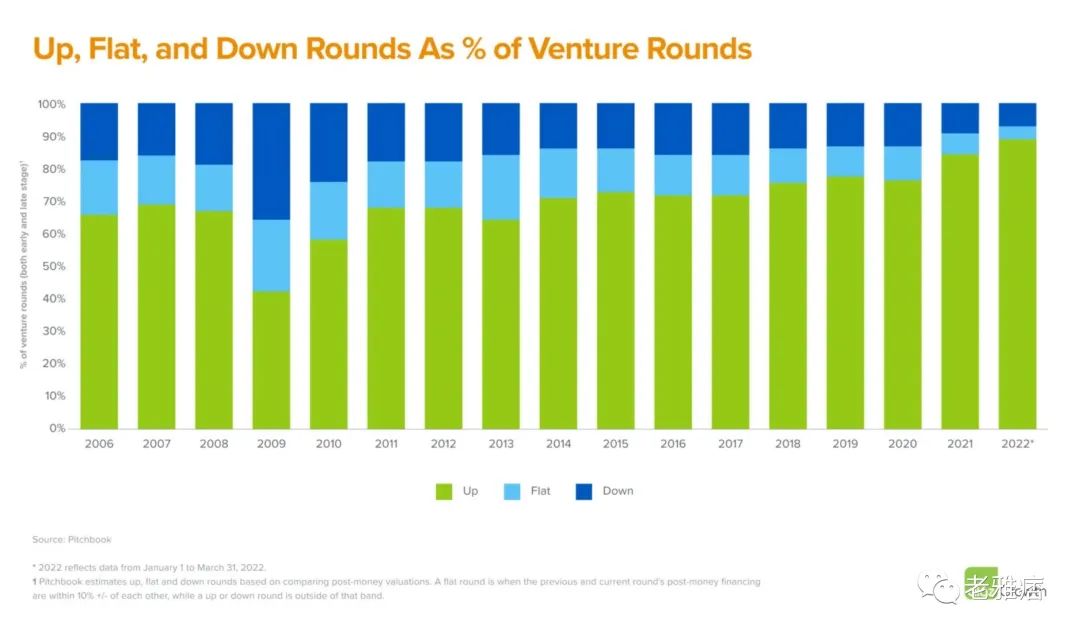

How do you evaluate and decide on the best financing options for your company when capital becomes more expensive?

Founders tend to think in terms of valuation and dilution, while investors may be more interested in knowing their minimum guarantee of earnings on the downside and the size of their potential earnings on the upside.

The purpose of this article is to help startups understand the different contractual terms used to increase overall valuation, how investors perceive and use these terms, and the implications to consider before signing, particularly on dilution.

first level title

Range from Equity to Debt

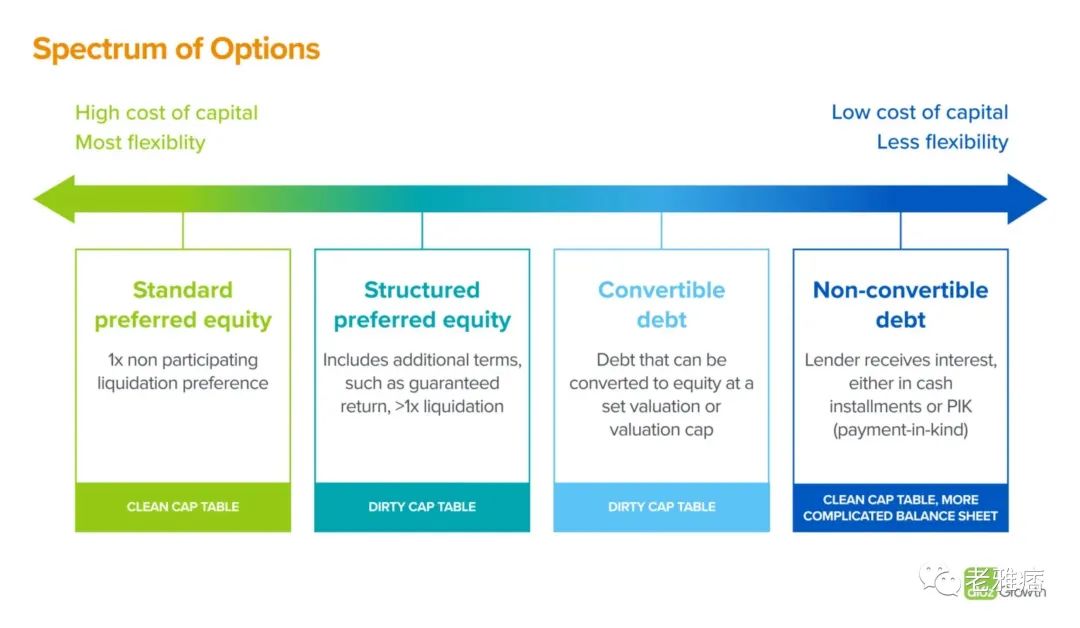

In practice, different options and terms can be combined, and in later sections we delve into the specific terminology used to optimize equity proposals and provide side-by-side comparisons of common scenarios. For simplicity, though, let's look at four advanced options: standard preferred stock, structured preferred stock, convertible notes, and non-convertible notes. These options can roughly be considered to be in the range of flexibility at the cost of capital cost and dilution.

Among them, structured preferred shares and convertible bonds are often considered "dirty term sheets" because they add deal terms that provide sweeteners to investors, such as increased potential earnings increments or higher guaranteed minimum returns.

first level title

The sweetness of the economic deal

Structuring terms and deals, despite being called "dirty", are not inherently good or bad, and we're not here to tell founders what the right terms are for their businesses. However, we do want to make sure founders understand the tradeoffs of structured deals. Regardless of the term sheet, founders focus on valuation. If the same amount of capital is raised on the same terms but at a higher price, the financing will be less dilutive to existing shareholders.

In reality, the best way to raise capital is to find the right balance between valuation and dilution to align incentives among investors, boards, founders, and employees. Here, we'll take a deep dive into some of the most common "sweeteners" used to boost overall valuations, and how they affect dilution and stakeholder alignment.

first level title

Warrants

Why it matters: The strike price is the core lever used to boost valuations, but the lower the warrant's strike price, the greater the chance of dilution. Penny warrants, in particular, are essentially free incremental stock in the company, so they depress the "real" price of financing.

first level title

secondary financing

What is a secondary financing: In a secondary financing, investors buy stock from existing shareholders. This is in contrast to primary financing where a company issues new shares in exchange for cash on the company's equity structure sheet. Investors can buy preferred stock at a higher valuation in one financing and also buy secondary equity (usually unprotected common stock) from a previous investor at a lower price.

Sometimes, investor demand may be relatively fixed, so any investment in secondary sales reduces the amount available for primary sales. Therefore, for companies with downstream funding needs, they may prioritize Tier 1 over Sub-tier.

first level title

conversion price

Why it matters: Convertibles allow lenders to earn returns (including interest) while participating in the company's upside, much like debt in less rosy scenarios. Founders typically want to set a switch price as high as possible, like pricing a funding round, to minimize dilution.

first level title

anti-dilution clause

Why it matters: For investors, anti-dilution offers greater safety at higher overall valuations. If the valuation falls later, especially at an IPO, they will get more shares to make up some or all of the difference. If valuations fall, it means (often significant) dilution for founders and other unprotected shareholders. While nearly all equity financings have price-based anti-dilution protections, "ratchet" protections are typically only present in structured transactions.

first level title

liquidation preference

What is a liquidation preference: A liquidation preference refers to who gets paid first, and how much, in the event of a liquidation. Priority refers to the order in which investors are paid back, with the highest priority investors getting paid first, which makes them the safest.

Multiples refer to the multiples that must be paid out on the original investment before lower tier investors are paid out. Typically, investors take a liquidation multiple of 1x, so they get their money back before the common stockholders get anything. However, the liquidation preference multiple can be greater or less than 1 times.

Liquidation preferences can also be participating or non-participating. A non-participating liquidation preference means that the investor receives the greater of the base liquidation preference or the value of the investor's pro-rata ownership of the company. Participating liquidation preference refers to the liquidation preference that investors receive after paying the liquidation preference and their pro rata ownership of the company's value.

For example, suppose a company is valued at $1 billion and there is an investor with a liquidation preference of 1x who invested $100 million and owns 20% of the shares. At the time of the sale, investors will receive the first $100 million and the remaining $900 million. They will then receive 20% of the $900 million based on their ownership stake: a total of $280 million, or 28% of the total equity value.

Why it matters: Liquidation preferences matter most in a down situation. If the company exits at a price per share that is higher than what investors paid for the preferred stock multiplied by the liquidation preference multiple, the preferred stock converts to common stock and, if they do not participate, the common stockholders receive Earnings are not affected. However, if the company exits at a lower price per share, or in the unfortunate event of bankruptcy, investors will get their investment (or a portion of it) back before common stockholders receive any gains.

1x liquidation preference is the standard for investors. It protects investment capital by guaranteeing investors' returns, preventing entrepreneurial teams from distributing dividends to investors' cash in proportion, and running away with investors' money. However, in down markets, when investors become more risk-averse, it is more common to liquidate at higher multiples.

first level title

PIK interest

What PIK Interest is: Unlike quarterly or annual cash payments, a "PIK" combines the original investment in securities with all the structure and protections. These in-kind payments can appear as dividends in structured equity transactions or as accrued interest in structured debt transactions.

Why it matters: PIK interest means no cash outflow during accrued equity or debt outstanding periods, but results in more shares, structured equity transactions, or more principal at the end of the term. This could mean more dilution or a larger repayment cash outlay. Typically, these PIK payments are compounded, so investors receive additional dividends or interest, which can add up to a considerable amount.

first level title

governance terms

Why it matters: Options are valuable to investors, especially given that many of the protections in structured deals (liquidity preferences, minimum returns, ability to repay in the form of debt) lapse at IPO.

first level title

Recapitalization / Forced Approval / Paid to Participate

Why it matters: A "restatement" or "force-approval" term sheet usually occurs when a company is having a relatively difficult time. This structure allows new investors to invest protected new funds as they are now top priority, and allows new investors to invest new funds in companies with lower liquidation priorities (for later stage companies that have raised significant funds, This point may become quite important). A "pay to participate" term sheet can have the same effect, but it also has the added effect of incentivizing existing investors in the company to continue participating in the company's financing.

first level title

What-If Scenario/Term Sheet

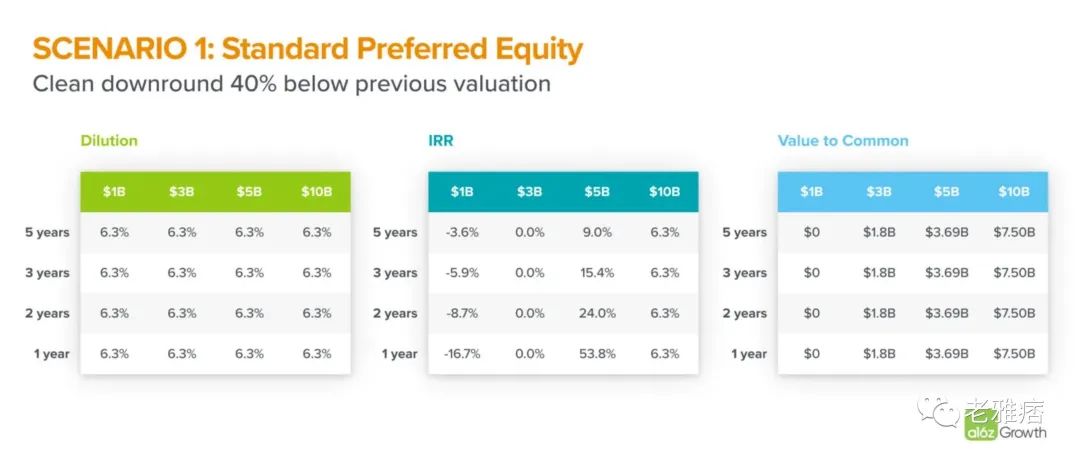

In each scenario, we present a sensitivity table that we use at a16z to quantify the company's internal rate of return (IRR), which is a way for investors to assess potential returns and dilution. For each proposal with a given structure, we will plug into the model to assess the cost of capital and dilution for the expected time frame and potential exit value.

secondary title

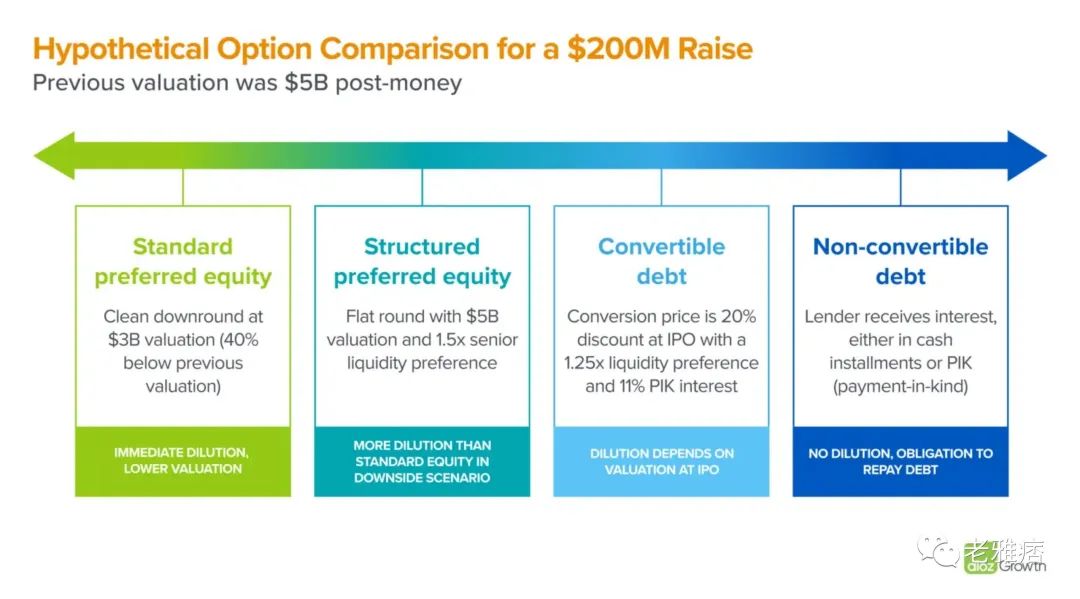

Scenario 1: Bleeding financing is about 40% lower than the previous valuation

A bleed financing is a financing method in which a company sells equity at a price per share lower than that issued in its previous financing. In our first scenario, the company would raise $200 million at a pre-money valuation of $3 billion, or 40% less than its previous valuation, in a bloodbath round via standard preferred stock. New investors now own about 6.3% of the company (excluding any anti-dilution adjustments to existing investor holdings that might be triggered). The new investors would own about 3.8 percent of the company if the company had done a parallel round of funding in its $5 billion pre-funding round.

As investors, we value a bleed round in much the same way as a premium round: we start from scratch, rather than being fixed at a previous valuation. We evaluate a company's performance, business model, market opportunity, management team to determine the valuation we are willing to pay. Sometimes this will be higher than the previous round's valuation, sometimes lower, but we try not to rely too heavily on the previous round's valuation and form our valuation based on our current assessment of the company's potential future cash flow generating capabilities. value perception.

Pros: Bleed financing keeps capital sheets clean, which is especially valuable for incentive alignment.

Cons: A bleed round dilutes existing equity more than a flat or premium round and may send a negative signal to the market. Additionally, bleed financing can affect employee morale, especially if it puts their options at risk.

For founders, taking a bleed round often means worrying: Will current employees who see their options and stock depreciate start looking for new jobs? Will future employees want to join? Will customers and partners be concerned about our ability to provide services? If we bleed financing now, will we have difficulties in financing in the future? These are legitimate concerns, and in bleeding financings, you need to be aware of them and be prepared to deal with them.

When a company is nearing an IPO, has more investors and employees with equity, and a clean cap table becomes more important, a bleed round may be the best option.

secondary title

Scenario 2: Structured preferred stock with 1.5x preferred liquidity preference

In our second scenario, the company raises $200 million at a $5 billion valuation. New investors will receive 1.5x preferred non-participating liquidity. Assuming no change in the share count, the new investor now owns approximately 3.8% of the company; in a merger, the new investor is also guaranteed a return of at least 1.5x before any prior investor or common equity holders share in the economic benefit . Most typically in an IPO situation, the preferred stock will convert on a 1:1 basis, so a liquidation preference above 1.0x does not ensure a return, although these investors may have negotiated a minimum return in the case of an IPO.

Pros: This structure results in an unchanged overall valuation with strong upside and less dilution than a bleed round.

Bottom Line: Structured preferred shares can help preserve overall valuations with less dilution on the upside. However, if the company does not perform as expected, the new investors will be rewarded before the old investors and common stockholders start to participate.

secondary title

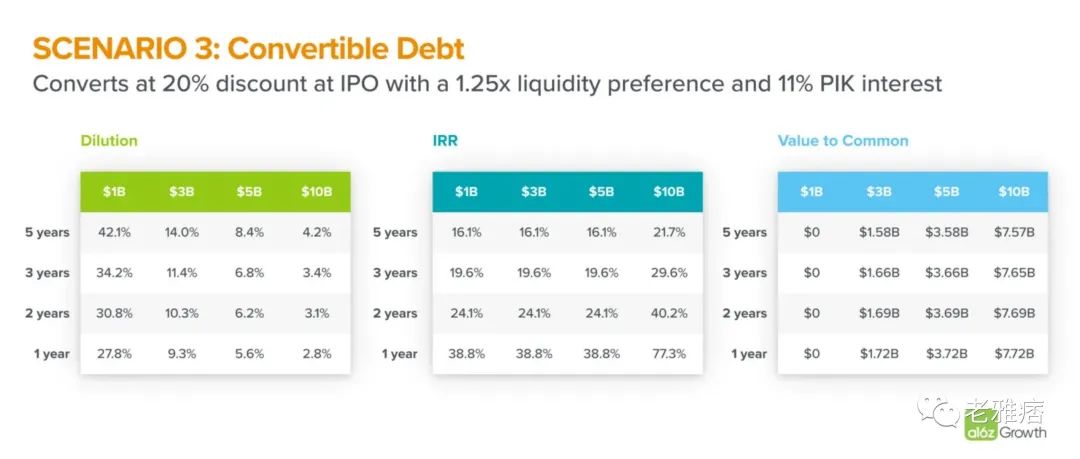

Scenario 3: USD 200 million convertible bond, convertible at 20% discount at IPO, with 1.25 times liquidity priority and 11% PIK interest

For our third scenario, the company would receive $200 million in convertible bonds at a conversion price of 20% discount to the IPO price, 11% PIK interest, and a preferred liquidity preference of 1.25 times. New investor ownership depends on IPO price and timing. As an example, if the company's valuation doubles from the previous round in two years, reaching $10 billion at the time of the IPO, the convertible bonds would convert to 2.4% of the company's shares. On the other hand, if the company's IPO price is $5 billion (the same as the previous valuation), the convertible bonds will convert to about 4.8% of the company's shares. If the company IPOs at $4 billion (20% below its previous valuation), the convertible bonds will convert to about 6.0% of the company's shares.

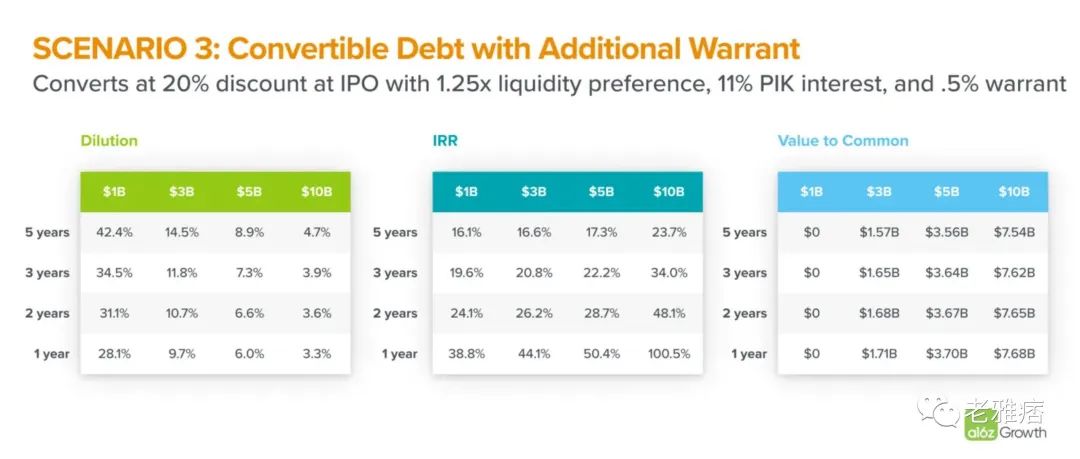

If we add a 0.5% warrant to the above scenario, this further benefits investors.

Note that since the dilution of the warrants is set before the conversion of the convertible debt, the warrants are also diluted along with the earlier preferred and common shares. The lower the value of the exit equity, the greater the dilutive effect of the convertible bond and therefore the dilution of the warrants and existing shareholders.

Advantages: This structure does not lead to changes in the overall valuation, and the specific degree of dilution can be determined based on the valuation at the time of IPO. If the company is temporarily in trouble and feels better about its future prospects at the time of IPO would be helpful.

Bottom Line: If the company outperforms standard preferred stock, convertible bonds help maintain overall valuation and will limit dilution. However, this introduces complications to the capital sheet and could cause serious dilution if the company does not perform as expected.

secondary title

Scenario 4: $200 million in debt, 5 years, 8% cash interest

In our final scenario, the company assumes $200 million in venture debt with a cash rate of 8% and a maturity of 5 years. The company pays an immediate fee of about $5 million at settlement (a direct deduction) and then has to pay $4 million quarterly over the next five years ($16 million in annual payments). At the end of the fifth year, the company must pay back $200 million. The company must also abide by the lender's agreement and submit detailed financial and other compliance reports to the lender.

Pros: Vanilla VC loans are cheap, easy, and keep the cap table clean.

Cons: Availability of venture debt depends on the health of the company. Risky loans may be less accessible during an economic downturn. As part of taking on risky debt, which is issued by a lender with a lower risk appetite, more covenants and reporting may be required. There can also be little flexibility as the company has to make regular cash interest payments and needs to make a lump sum principal payment at the end of 5 years which will affect cash flow.

Venture debt takes precedence over equity, so in the event of an adverse situation, the first capital to be distributed will be distributed to debt holders before any equity holders.

Getting the next round of funding or cash flow is the number one priority for founders, and that job gets harder when the market turns. But if you can achieve the right balance of dilution, valuation, and flexibility in your funding strategy, it can be a strategic advantage that will not only get you through the recession, but put you in a good position when the market recovers Gain market share and grow.