cryptocurrency

Original translation: zik

This article is from the WeChat public account The SeeDAO.

cryptocurrencyThe open source and permissionless nature of the protocol has reignited the debate about public goods. In fact, the transparency and accessibility of the blockchain has reshaped the model of free exchange and federation. However, while an encryption protocol operates as an open network, is an encryption protocol really public if it is all composed of private capital? Issues of scope, access, and ownership complicate our understanding of public goods on the Internet. Public goods also depend on shared moral conditions, since any "good" must be defined in terms of a particular community's value system. Based on these considerations, we advocate strengthening the definition of "public goods" in order to serve others and promote the prosperity of civilization.

To live in this world together essentially means that this world of things exists among those who share it, just as a table exists among those who sit around it. – Hannah Arendt, 1958

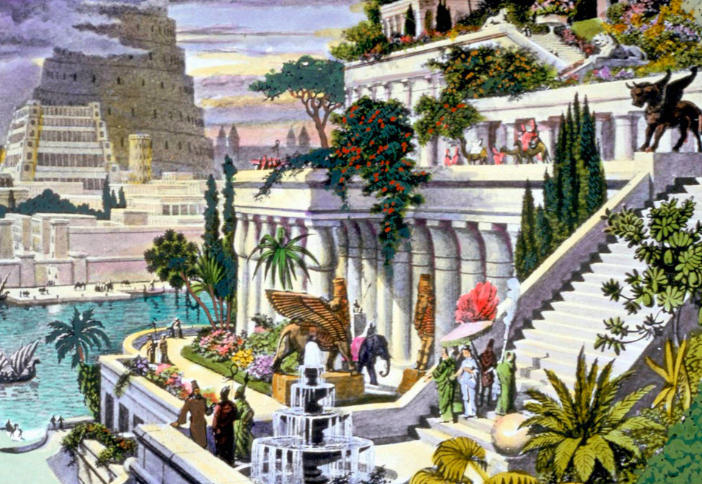

image description

Artist unknown, 19th century.

Commons, whether natural resources or human creations, pervade our interconnected world. We as a society manage, share and maintain them. Although not perfect in the way they are structured and managed, they still engage us in conversations, debates, and shared concerns (Honig, 2017). The natural landscape and the built environment are not just things, they are also points of contact with culture that draw our attention to the common good.

The Roman aqueduct of the Pont du Gard has been recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Painting by Hubert-Robert, 1787.

privacyprivacyIt is itself a public good. Online media archives and open digital infrastructures also seem to fit this definition.

decentralizeddecentralizedA type of finance. Fundamentally, these token holders only care about one common goal: price.

When we think that encryption protocols should be regarded as public goods in the economic sense, further discussions on what is beneficial to the public? Some crypto communities declare their ambitions to solve large-scale coordination problems, establish post-state forms of sovereignty, and level the global playing field. But to create a grand and egalitarian society requires a broader vision of public goods, and imagination based on economics alone is not enough.

Ancient ruins used as public baths. Hubert-Robert (1798).

first level title

01

public range

Our new understanding of public goods begins with exploring the notion of commons. What makes something "public"? And what constitutes "public"?

The term "public" in its colloquial sense is understood as something that belongs to the people and is free to use—such as parks, roads, and public lands. The strongest "publicity" of encryption protocols is based on the principles of openness and permissionless access. Blockchains overcome a key limitation of Web 1 and Web 2 "publicness": they cannot meet the criteria of "unimpeded access". The so-called "public spaces" on the Internet are nothing like the parks in our cities. They are just other people's private servers, and access to them can be revoked at will. By contrast, encryption protocols deliberately enforce "unimpeded access".

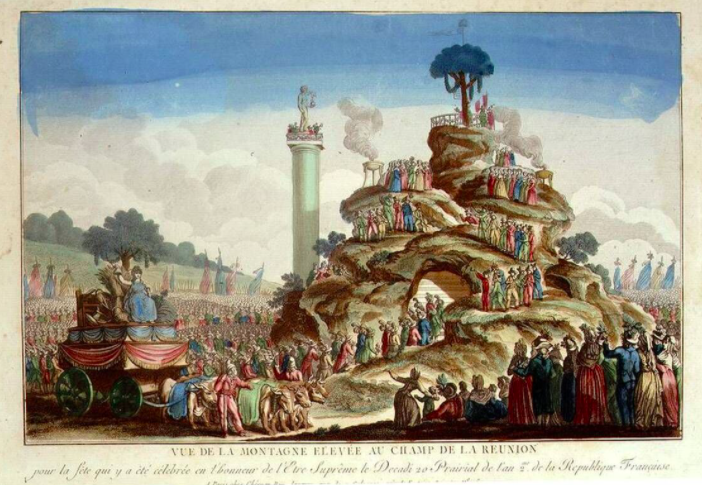

But "public" is not just permission to enter public space. Another key definition of "public" is "public", that is, a group related to certain political associations. In 17th-century England, there was a new uncensored press publishing articles of public opinion, including notes from salon meetings and critical journals. These publications often blamed the state and for the first time brought together "the private as the public" (Habermas, 1989). Less than a century later, French revolutionaries inspired a new national sense of self by organizing festivals, erecting monuments, and creating new public spaces (Ozouf, 1975). In both cases, political groups elevate themselves to the status of institutions by establishing new places for storytelling—places where people begin to identify themselves as part of a collective whole, the public.

The Festival of the Supreme Being, organized in 1794 to inaugurate the new state religion after the French Revolution.

This notion of the public as a self-aware entity also has a place on the Internet, fueled by the publication and distribution of media. Publishing a Web document or software application is more than making something public: it is a publicity in itself (Warner, 2002). Cryptocurrency advocates often draw on this notion, referring to token holders as “communities” and likening protocols to nations with citizens. Sovereign currencies created by blockchains can undoubtedly be compared to sovereign national fiat currencies, and their stability means that APIs cannot be modified or revoked without broad consensus.

These ideas inform the notion of cryptographic protocols as public goods, yet they intertwine to present a complex picture. Despite the "open" nature of encryption protocols, there is no satisfactory answer to the extent to which they are open to the public.

In today's crypto ecosystem, token-based membership determines key factors such as resource allocation, on-chain incentives, and off-chain decision-making. Blockchain’s censorship resistance looks like a solution that can protect the world, but in fact, “pay-to-participate” is another way to limit access. A protocol may be owned by thousands, even millions of stakeholders, but not everyone benefits from it - only those with the time, expertise, or resources to participate.

So what does it mean to define the public as a group of users? The Web 2 platform has taught us an important lesson. The social media platforms that dominate the web today claim to be tools for “communities” of users who choose to participate — but these platforms generate a wide range of negative externalities: effects on third parties who are unwilling to pay. In addition, platform externalities also include the invasion of personal privacy, the spread of misinformation, the devaluation of creative labor, and even the destabilization of democratic processes. These implications are often cited as the primary motivation for Web 3 practitioners today to create a sovereign space grounded in public accountability.

Social platforms provide us with an example of a misunderstood public, but the nascent Web 3 "public space" has similar problems with definition, scope, and representation. The equivalence of stake and voice in cryptocurrencies is reminiscent of early American democracy, when political representation was conditional on property ownership. Under this system, only 6 percent of the American population is eligible to vote—an exclusionary political system that is laughable by today's standards (Ratcliffe, 2013). Recall that universal suffrage, human rights, and public services that we enjoy today are the result of the struggle for a voice for those excluded from certain publics. In fact, "anti-public" theories specifically target groups that are not accepted in the larger public sphere, members of which may not be seen as individuals (Warner, 2002).

Therefore, it is clear that defining the scope of the public is the key to understanding what constitutes a public good. If we equate public membership with currency ownership, we ignore other important stakeholders and miss opportunities to build coalitions. The most important members of the crypto community today are those who hold the most tokens, meaning that even small holders are effectively excluded from discussions about their own interests. Furthermore, within this particular public there are those who hold very different views on the concept of public goods. By engaging with underrepresented and broadly marginalized groups in the crypto community, we can gain a deeper understanding of what the publics we are building really are, and how best to serve them.

When we think of the public, we should think broadly. That's not to say we have to see everyone in the world as part of our public. As we emphasize in our article on small groups, we also promote small, self-selected communities and groups based on trust. But, taking into account possible impacts (both positive and negative) on marginalized groups—whether non-coin holders, non-technical family members, or simply future participants in this public domain—we at least increase access to The potential for greater public good and reduces the risk of negative externalities.

Simply put: who belongs to the great post-state society this crypto community aims to build? To paraphrase Michael Warner: The public always goes beyond a known agreement. It is a relationship between strangers, with its historical contingencies and cultural complexities. The public is made up of friends you've never met, with whom you share cultural coordinates without knowing it. How can the things we build benefit the greatest number of people?

first level title

02

The Moral Basis of Public "Wellbeing"

How do we determine what constitutes the public's "well-being"? So far, we have started to question "who is the public?" However, even with the understanding that the public = token holders, it seems that we still have not been able to find the final answer. Who are these token holders? What beliefs do they hold?

Consider a typical public good: a park. We can generally say that park visitors are "users" of this public space, or anyone within driving distance is adequately served. But this categorization feels distinctly unsatisfactory. "User" fails to capture meaningful details about this group, such as the fact that they all value free access to protected forests or coastlines. Why are parks more popular than public parking lots? This brings us to an important realization: any definition of a public good presupposes a shared understanding of the public good, and why.

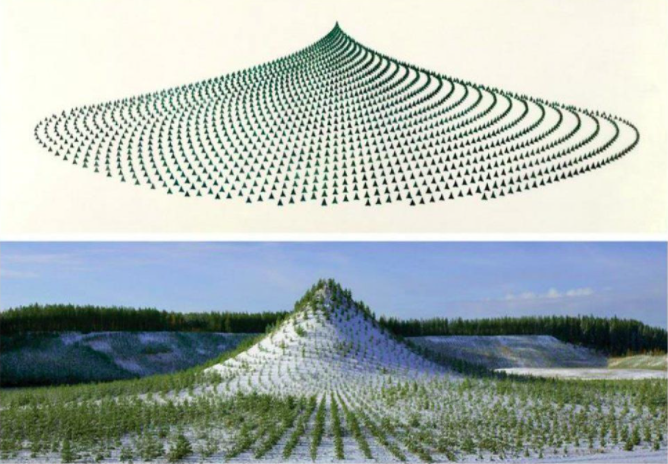

Tree Hill - A Living Time Capsule - 11,000 trees, 11,000 people, 400 years (1992-96) Ylojarvi, Finland.

A social group is united not only by the things it uses, but by many shared characteristics, including geography, race, religion, taste, culture, history, and values. This is why, regardless of their claimed universality, instances of public goods are always local. Locality is created and felt through shared space, time or experience. Without the assumptions and norms that have developed in this common context, it is impossible to identify what is in the public interest and create the space for it. Thus, even by economists' definition, public goods will always reflect the common background, common beliefs, and moral sensibilities of certain groups, in other words, their value systems.

Public libraries, public education, national cultural relics, and clean running water are the four public things that embody the moral basis of public goods. Communities that value independent learning and shared knowledge spaces build public libraries. Public schools are valued when a culture sees a common ground in math, science, language, and history as enriching civic life. Nations designate and protect historical artifacts because their people see them as something of intrinsic value connected to their heritage. Finally, we provide clean water for all because we believe all life is equally valuable. This humanistic value is why accidents like the Flint water crisis (failure of basic infrastructure) are generally perceived as humanitarian crises: certain lives are seen as worthless and not treated as they should be.

Each of the above examples is a different idea of the meaning of life: based on a perception of what constitutes "well-being" (Taylor, 1977). Public goods are non-excludable and non-rivalrous, but more importantly, they are items that satisfy shared values.

The four public goods mentioned above are maintained by social institutions that share a belief in their value to the wider public. But how many people pay attention to the "public goods" funded in the cryptocurrency space, and notice whether their value is reflected? UNI holders, or Ethereans holders, what are their common values?

The crypto community has an ostensibly libertarian spirit, where "decentralization" often represents the self-sovereignty of the community. With wealth creation in the space, cryptocurrencies should indeed create public goods for the different values of their different communities. There's even a popular meme called "crypto allows communities to encode value into currencies". But in practice, there is little room for discussion or implementation of different values. Lack of ways to live up to our shared values - which is why we can only default to the lowest common denominator: profit.

governancegovernanceIn the situation where the weight is too high. In our view, this poses a risk of centralization. When protocol politicians are not empowered or formally charged to represent the interests of all, but only their own, the result is a homogeneous and self-interested group of whales that can dictate what is deemed good for the network. There is no concept of "public servant" in the encryption field.

financingfinancingMechanism basis) proposes a model that equates public goods with market signals (Vert et al., 2018). One could argue that values are "priceable" in this model, and if people "vote with their dollars to determine their values," then the market acts as a vehicle for funding those values, whether they are explicit or not. In fact, quadratic voting does seem to be able to boost the relative voice of an enthusiastic minority.

But while voting has symbolic power, this model ignores an important fact: We do not discover shared value through personally revealed preferences. Open discussions about what is valuable are important if public goods are to satisfy shared values. Many protocols have learned this lesson in governance: discussion and consensus building are necessary prerequisites for voting. Again, the discussion of value is as important, if not more important, than the act of voting itself. Value systems are cultivated through narrative and negotiation in public forums.

first level title

03

Public goods, a new definition: positive externalities

What we have learned so far about the complex ways in which publics can be defined suggests that extending our concept of publics to include more dimensions may lead to better results. We also see that public goods are based on shared values in certain regions. So, with these concepts, can we give a better definition of public goods?

We need the types of public goods that can be crafted by the digital community while avoiding the disruptive scaling effects of Web 2 platforms. along with

text

Other examples of positive externalities for cryptocurrencies are more in the bud. Today, core contributors to open source projects remain underfunded, even though entire industries are built on their software. With the infrastructure provided by companies like Gitcoin and Radicle, protocol vaults are poised to significantly expand their funding support for open source code, both within and outside the cryptocurrency industry. We are already seeing signs of this shift, with more private and public funding being channeled into the support of open source projects, both within and outside the cryptocurrency industry.

Likewise, normalizing open organization APIs and civic engagement are objects of public interest to any contemporary liberal and democratic advocate. APIs that are open, immutable, and publicly governed greatly curb the power of centralized organizations and empower user agency, who can now dictate their own interfaces and services. If blockchains put pressure on centralized corporations and governments to make their APIs open and irrevocable, it will mark a major paradigm shift towards accessible and accountable institutions. Finally, cryptographic protocols reintroduce participatory governance of public systems as part of everyday life. We can only hope that increasing people’s participation in local governance with transparency and ease is one of the external effects of cryptocurrencies.

Any one of these public goods, whether current or potential, is a good beyond economic meaning itself. They satisfy the values of privacy, the virtues of free sharing of work, libertarianism, accountability, and democratic participation, and combine common interests for parties beyond today's Web 3 users.

This points to a useful feature of our new definition. Understanding public goods as positive externalities allows us to treat as our beneficiaries people who are not normally members of the public. This definition stands in stark contrast to economic discourse, in which non-contributing users of certain public goods are seen as "free riders," suggesting a market failure. How can we treat these users as “free riders” when it is clearly in the interest of society to promote the creation and consumption of public goods—whether they be vaccines, public libraries, or open source code? The concept of positive externalities makes the interests of others self-evident. In fact, this quality is consistent with the principle of trusted neutrality. Applied to public goods, credible neutrality suggests that there should be no privileged class of "citizens" and that all should benefit equally.

Positive externalities are thus an important variation on a familiar theme in the cryptosphere: positive-sum games. By now, most crypto natives recognize that relationships and value creation are largely of this type, that the building of the game and the contributions of the shillings have a synergistic additive effect. As protocols and infrastructure evolve and become more culturally entrenched, the degree of their positive externalities should increase proportionally.

An interesting case study is Fair Launch Capital. While the project does not explicitly state a mission of public interest, it hints at a possible social model worthy of further exploration. In simple terms, Fair Start Capital is a small group of facilitators who fund promising projects. The founders of these projects must be willing to forego their token distribution as founders, distributing their tokens “fairly” in exchange for startup capital. If the founders made some money in the process of deploying the protocol, they will be required to "pay it forward", funding subsequent project teams to launch their protocol, and distribute tokens in the same way.

The model of a fair launch is interesting for several reasons. First, the facilitation group does not directly capture financial value; it exists to perpetuate the organization. Second, fair startup capital is not a hard infrastructure, but a social agreement, an institution that relies on dedication and value alignment to maintain. Third, those who benefit are not the same as those who provide services. This brings us to a surprising feature of this new form of public goods: One way to embody positive externalities is to regard other people's success as your own.

Zilker Park Kite Festival, held annually in Austin, Texas.

With this idea of positive externalities, what kind of public goods can we create, and how? If a public good always serves its user base at a level of local value, then the best inspiration should be found by looking at the public goods we are already in. In addition to our on-chain identities, we, the authors of this article, are from Berlin and New York. As citizens of these places, we benefit from parks, clean air, sanitation, and public transportation; at the same time we are disturbed by excessive policing, deforestation, and slow vaccine deployment. We have friends who have received public art grants and writing grants to make sure they can provide education to students who have lost access to school.

As “members” of these local spaces, we connect with those who share our needs, desires, and concerns. We would all benefit from more green space, quality low-cost housing, and better access to healthy products. Can public goods funders and builders from the crypto space intervene in these areas? The crypto world has managed to build infrastructure that exists outside of nation-state systems, yet our lives are still embedded in localities, communities, and nations. The vision of a truly global DAO representing billions of people is an illusion. However, if we apply the principle of "positive externalities" to future citizens living locally, the public goods constructed by the agreement can appear more like community-driven industrial policy.

This might look like Equity Startup Capital provides start-up capital to small local businesses. also like

first level title

04

Ethereum

EthereumThe project envisions a "world computer," a coordinated system for global prosperity. Along with thousands of others, we joined the crypto world in 2016 and 2017 with the ambition to make society a better place. Right now, however, most of us are stuck checking our portfolio balances. Are we ignoring this core belief?

Each of us is a beneficiary of past social public goods. We are humbled by these grandiose projects: cathedrals, the Grand Canal, sanitation, the expansion of mass literacy—they teach us that the “well-being” of public goods can also be measured by their longevity. To be worthy of these great works, we must extend our timelines. We want to ensure positive outcomes, not just for token holders or protocol participants, but for the world that co-extenses with these infrastructures. How do we take advantage of the immutability provided by encryption protocols to create something that outlasts us and lay the groundwork for a long-lasting civilization?

To answer this question, we need only consider public goods that satisfy this definition. Permanent land reserves, the global seed vault, the Internet itself as the underlying communication technology of the contemporary world. These are not only public goods, but cultural practices that sustain these goods from generation to generation. Public goods are enacted by social institutions that reset patterns of behavior for the public good.

Cryptographic protocols provide the building blocks of social institutions that enable them to meet the challenges of today's online culture. Many are already ambitiously looking for impactful ways to spend their multibillion-dollar coffers. And it’s not just economic value that flows through these cryptoeconomic systems: people’s time, attention, and energy are all resources that can be channeled. However, much of what is being built in cryptocurrency today is a self-referential, self-serving money game. "

Buckminster Fuller,1/2,000.000 scale "Playground Map", developed by World Game Research Institute, scaled by Kara Kittel.

references

references

Arendt, Hannah. 'The Human Condition.' 1958.

Buterin, Vitalik et al. 'Liberal Radicalism: A Flexible Design For Philanthropic Matching Funds.' 2018.

Habermas, Jürgen. 'The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society.' **(T. Burger, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

Honig, Bonnie. 'Public Things: Democracy in Disrepair.' New York: Fordham University Press, 2017.

Ratcliffe, Donald. 'The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787–1828.' Journal of the Early Republic, 2013. pp. 33.

Taylor, Charles. 'What Is Human Agency?' In Theodore Mischel (ed.), The Self: Psychological and Philosophical Issues. Rowman & Littlefield. 1977. pp. 103.

Warner, Michael. 'Publics and Counterpublics.' New York: Zone Books, 2002.