From Libya to Iran: Countries in Blackout, Bitcoin Miners Uninterrupted

- Core Argument: The article reveals how Bitcoin mining in countries like Iran and Libya exploits heavily subsidized, cheap electricity for arbitrage, leading to the crowding out of public resources, exacerbating already fragile power crises, and evolving into a form of resource extraction where a few benefit while society bears the cost.

- Key Elements:

- Industrial electricity prices in Iran and Libya are extremely low, approximately $0.01 and $0.004 per kilowatt-hour respectively, creating a massive arbitrage opportunity for Bitcoin mining, making even obsolete old mining rigs profitable.

- In Iran, despite the government legalizing mining and attempting to regulate it, about 85% of mining activities are unlicensed, and "privileged mining farms" connected to power structures enjoy exemptions, rendering regulation ineffective.

- In Libya, due to national division and fragmented governance, mining bans are difficult to enforce. Mining activities grow wildly in a gray area, primarily operated by foreigners using smuggled old mining equipment.

- Mining consumes vast amounts of electricity, peaking at about 2% of Libya's total national power generation and worsening electricity shortages in Iran caused by sanctions and an aging grid, directly impacting public services like hospitals and schools.

- The profits from mining (Bitcoin) are highly globalized and easily transferable, but the cost of the electricity consumed is borne by the local society, creating an asymmetric structure of privatized gains and socialized costs.

- Mining has not brought the expected foreign exchange earnings or substantive industrial development to either country. Instead, it resembles a privatization of public resources facilitated by institutional loopholes and price distortions, with ordinary citizens ultimately bearing the cost.

Introduction: The "Export Industry" of Power-Outage Nations: How Electricity Becomes Bitcoin

On a summer night in Tehran, the heatwave feels like an airtight net, making it hard to breathe.

Amid the recurring power crises of recent years, the summer of 2025 became the most unbearable moment for this Iranian capital city; that year, the city experienced one of the most extreme heatwaves in nearly half a century, with temperatures repeatedly exceeding 40 degrees Celsius, forcing 27 provinces to implement power rationing and leading to the closure of numerous government offices and schools. In local hospitals, doctors had to rely on diesel generators to maintain power—if the blackouts lasted too long, ventilators in intensive care units could stop working.

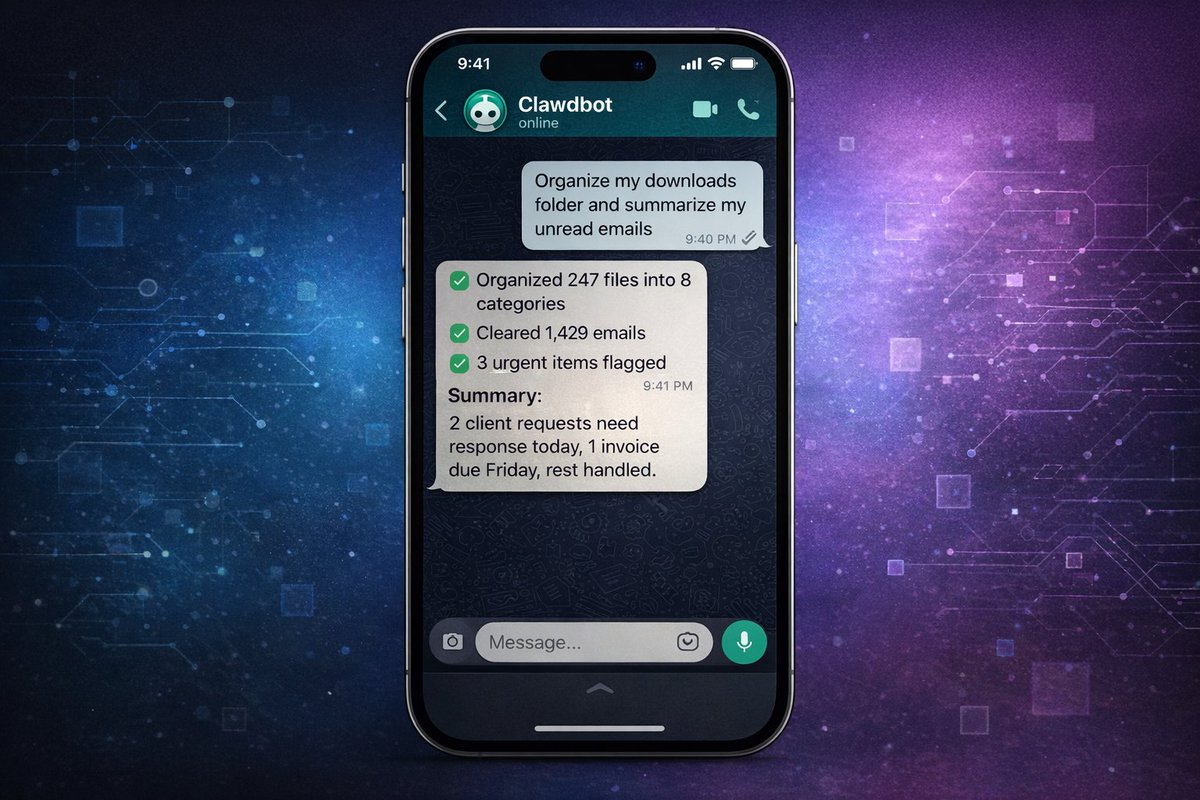

Yet, at the city's edge, behind walls, another sound is more piercing: the deafening roar of industrial fans as rows of Bitcoin mining rigs operate at full capacity; LED indicators of all sizes twinkle like a sea of stars in the darkness, and the electricity here almost never cuts out.

Across the Mediterranean in the North African nation of Libya, the same scene plays out daily. Residents in the eastern region have long grown accustomed to daily rolling blackouts lasting 6 to 8 hours; food in refrigerators often spoils, and children do their homework by candlelight. But in abandoned steel mills outside the cities, smuggled-in old mining rigs run day and night, converting the country's nearly free electricity into Bitcoin, which is then exchanged for dollars via cryptocurrency exchanges.

This is one of the most absurd energy stories of the 21st century: in two nations ravaged by sanctions and civil war, electricity is no longer just a public service but is treated as a hard currency that can be "exported."

Image description: Two Iranian men sit outside their mobile phone shop, with only emergency lights illuminating the interior as a power outage leaves the street in darkness.

Chapter One: The Power Run: When Energy Becomes a Financial Instrument

The essence of Bitcoin mining is a game of energy arbitrage. Anywhere in the world, as long as electricity is cheap enough, mining rigs can be profitable. In places like Texas, USA, or Iceland, mine operators meticulously calculate the cost per kilowatt-hour, and only the latest generation of efficient miners can survive the competition. But in Iran and Libya, the rules of the game are entirely different.

Iran's industrial electricity price is as low as $0.01 per kilowatt-hour, and Libya's is even more extreme—around $0.004 per kilowatt-hour, one of the lowest electricity prices in the world. Such low prices are possible due to massive government subsidies on fuel and artificially suppressed electricity tariffs. In a normal market, such prices wouldn't even cover the cost of generation.

But for miners, this is paradise. Even old, obsolete mining rigs from China or Kazakhstan—equipment long considered electronic waste in developed countries—can still turn a comfortable profit here. According to official data, Libya's Bitcoin hash rate accounted for about 0.6% of the global total in 2021, surpassing all other Arab and African nations and even some European economies.

This figure might seem small, but in Libya's context, it is profoundly absurd. This is a country with a population of only 7 million, a grid loss rate as high as 40%, and daily rolling blackouts. At its peak, Bitcoin mining consumed about 2% of the nation's total electricity generation, equivalent to 0.855 terawatt-hours (TWh) annually.

In Iran, the situation is even more extreme. The country possesses the world's fourth-largest oil reserves and second-largest natural gas reserves, so theoretically, it shouldn't lack power. However, U.S. sanctions have cut off its access to advanced power generation equipment and technology, coupled with an aging grid and chaotic management, leaving Iran's power supply perpetually strained. The explosive growth of Bitcoin mining is pulling this taut string to its breaking point.

This isn't ordinary industrial expansion. It's a run on a public resource—when electricity is treated as a "hard currency" that can bypass the financial system, it no longer prioritizes hospitals, schools, and residents but flows to the mining rigs that can convert it into dollars.

Chapter Two: Two Countries, A Tale of Dual Mining

Iran: From "Exporting Energy" to "Exporting Hash Rate"

Under extreme sanction pressure, Iran chose to legalize Bitcoin mining, transforming its cheap domestic electricity into globally tradable digital assets.

In 2018, the Trump administration withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed "maximum pressure" sanctions. Iran was kicked out of the SWIFT international settlement system, could not use dollars for international trade, saw its oil exports plummet, and its foreign exchange reserves dried up. In this context, Bitcoin mining provided a convenient "energy monetization" side door: no SWIFT needed, no correspondent banks, just electricity, mining rigs, and a pipeline to sell the coins.

In 2019, the Iranian government formally recognized cryptocurrency mining as a legal industry and established a licensing system. The policy design seemed "modern": miners could apply for licenses to operate mines at preferential electricity rates, but were required to sell the mined Bitcoin to the Central Bank of Iran.

In theory, this was a win-win-win solution—the state exchanged cheap electricity for Bitcoin, then used Bitcoin for foreign exchange or imports; miners gained stable profits; and grid load could be planned and regulated.

However, reality quickly veered off course: Licenses existed, but the gray area was vast.

By 2021, then-President Rouhani publicly admitted that about 85% of Iran's mining activity was unlicensed; underground mines sprang up like mushrooms, from abandoned factories to mosque basements, from government office buildings to ordinary homes, mining rigs were everywhere. The deeper the electricity subsidy, the stronger the arbitrage motive; the laxer the regulation, the more electricity theft resembled a "default benefit."

Faced with worsening power crises and illegal mining consuming over 2 gigawatts, the Iranian government announced a temporary ban on all cryptocurrency mining activities from May to September that year, lasting four months. This was the harshest nationwide ban since legalization in 2019.

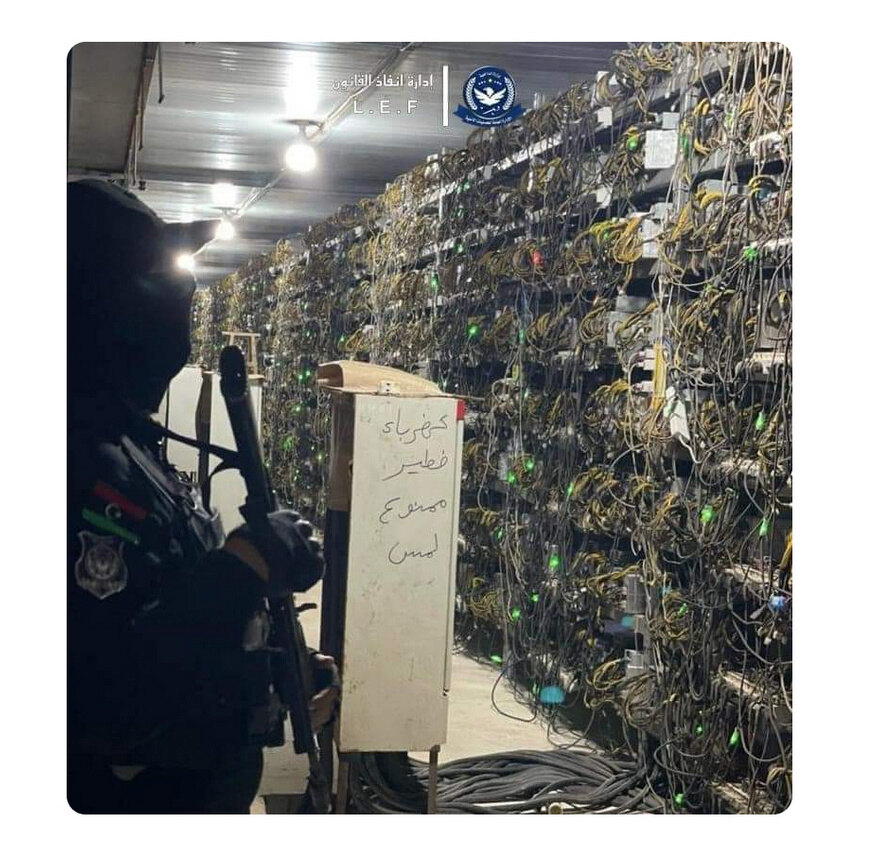

During this period, the government organized large-scale raids: the Ministry of Energy, police, and local authorities stormed thousands of illegal mines, confiscating tens of thousands of mining rigs in the second half of 2021 alone.

Yet, after the ban ended, mining activity quickly rebounded. Many confiscated rigs were put back into use, and the scale of underground mines grew rather than shrank. This "crackdown" was seen by the public as a brief performance: ostensibly targeting illegality, but in reality failing to address the underlying issues, while allowing some well-connected mines to expand.

More crucially, multiple investigations and reports pointed out that entities closely linked to power structures had entered the industry on a large scale, forming "privileged mines" enjoying independent power supply and law enforcement immunity.

When mines are backed by "untouchable hands," so-called crackdowns become political theater; and the public narrative is more pointed: "We endure the darkness just to keep the Bitcoin machines running."

Source: Financial Times

Libya: Cheap Electricity, Shadow Mining

A street wall slogan in Libya condemns "buying and selling relief materials is illegal," reflecting public moral anger over unfair resource distribution—similar sentiments simmer quietly against the backdrop of electricity subsidies being diverted for mining.

Libya's mining script is more like "wild growth in the absence of institutions."

Libya, this North African nation (population approx. 7.3-7.5 million, area nearly 1.76 million sq km, the fourth largest in Africa by area) is located on the southern coast of the Mediterranean, bordering Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and others. Since the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, the country has been mired in prolonged turmoil: recurring civil war, numerous armed factions, and severely fragmented state institutions, creating a state of "managed fragmentation" (relatively controlled violence levels but a lack of unified governance).

What truly propelled Libya into a mining hotspot is its absurd electricity pricing structure. As one of Africa's largest oil producers, the Libyan government has long provided massive subsidies, keeping electricity prices at around $0.0040 per kilowatt-hour—a price even lower than the fuel cost of generation. In a normal country, such subsidies aim to ensure public welfare. But in Libya, it became a massive arbitrage opportunity.

Thus, a classic arbitrage model emerged:

- Old mining rigs obsolete in the West and Europe remain profitable in Libya;

- Industrial zones, abandoned factories, and warehouses are naturally suited to hide high-power loads;

- Equipment imports are restricted, but gray channels and smuggling keep machines flowing in;

Although the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) declared virtual currency transactions illegal in 2018, and the Ministry of Economy banned the import of mining equipment in 2022, mining itself has not been explicitly prohibited by nationwide law. Enforcement often relies on peripheral charges like "illegal electricity use" or "smuggling," and is weak in the fragmented reality of power, leading to the continuous expansion of gray areas.

This state of "banned but not eradicated" is a typical manifestation of power fragmentation—bans from the Central Bank and Ministry of Economy are often difficult to enforce in eastern Benghazi or southern regions. Local militias or armed groups sometimes tacitly allow or even protect mines, leading to wild growth in the gray zone.

Source: @emad_badi

Even more absurd is that a significant portion of these mines are operated by foreigners. In November 2025, a Libyan prosecutor sentenced nine individuals operating a mine inside the Zliten steel plant to three years in prison, with equipment confiscated and illegal gains recovered. In previous raids, authorities detained dozens of Asian nationals operating industrial-scale mines using old rigs phased out from China or Kazakhstan.

These old devices are long unprofitable in developed countries, but in Libya, they are still money-printing machines. Because electricity is so cheap, even the least energy-efficient miners can turn a profit. This is why Libya has become the resurrection ground for the global "mining rig graveyard"—electronic waste discarded in Texas or Iceland finds a second life here.

Chapter Three: Crumbling Grids and Energy Privatization

Iran and Libya took two different paths: one attempted to incorporate Bitcoin mining into the state apparatus, the other long allowed it to linger in the shadows of the system. But the destination is the same—widening grid deficits, and the political consequences of resource allocation are beginning to show.

This is not merely a technical failure but a result of political economy. Subsidized electricity creates the illusion that "electricity is worthless"; mining provides the temptation that "electricity can be monetized"; and the power structure determines who can cash in on this temptation.

When mining rigs share the same grid with hospitals, factories, and residents, the conflict is no longer abstract. Blackouts damage not just refrigerators and air conditioners, but also surgical lights, blood bank refrigeration, and industrial production lines. Every instance of darkness is a silent scrutiny of how public resources are allocated.

The problem lies in the highly "portable" nature of mining profits. Electricity is local, its cost borne by society; Bitcoin is global, its value can be transferred instantly. The result is an extremely asymmetric structure: society bears the electricity consumption and blackouts, while a few capture the cross-border mobile profits.

In countries with sound institutions and abundant energy, Bitcoin mining is typically discussed as an industrial activity; but in countries like Iran and Libya, the nature of the problem itself changes.

Emerging Industry, or Resource Plunder?

Globally, Bitcoin mining is seen as an emerging industry, even a symbol of the "digital economy." But in the cases of Iran and Libya, it more closely resembles an experiment in the privatization of public resources.

If it were to be called an industry, it should at least create jobs, pay taxes, accept regulation, and bring net benefits to society. But in these two countries, mining is highly automated, creating almost no jobs; a large number of mines operate illegally or semi-legally, contributing little tax revenue, and even licensed mines lack transparency in their revenue flows.

Cheap electricity originally existed to ensure public welfare. In Iran, energy subsidies have been part of the "social contract" since the Islamic Revolution—the government uses oil revenues to subsidize electricity, and the people accept authoritarian rule. In Libya, electricity subsidies were also a core part of the welfare system inherited from the Gaddafi era.

But when these subsidies are used for Bitcoin mining, their nature fundamentally changes. Electricity is no longer a public service but a means of production used by a few to create private wealth. Ordinary citizens not only do not benefit from it but pay the price—more frequent blackouts, higher costs for diesel generators, and more fragile medical and educational services.

More importantly, mining does not bring real foreign exchange income to these countries. In theory, the Iranian government requires miners to sell Bitcoin to the central bank, but the actual implementation is questionable. In Libya, no such mechanism exists. Most Bitcoin is exchanged for dollars or other currencies on overseas exchanges, then funneled out through underground banks or cryptocurrency channels. These funds neither enter the state treasury nor flow back into the real economy but become the private wealth of a few.

In this sense, Bitcoin mining resembles a new form of "resource curse." It does not create wealth through production and innovation but extracts public resources by exploiting price distortions and institutional loopholes. And those who pay the price are often the most vulnerable groups.

Conclusion: The True Cost of a Bitcoin

In a world of increasingly scarce resources, electricity is no longer just a tool to illuminate darkness but a commodity that can be transformed, traded, and even plundered. When a nation treats electricity as a "hard currency" for export, it is essentially consuming the future meant for public welfare and development.

The problem is not with Bitcoin itself, but with who controls the allocation of public resources. When such power lacks constraint, the so-called "industry" becomes merely another form of plunder.

And those sitting in the darkness are still waiting for the lights to come back on.

"Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced."