Vitalik: Decentralization Without Losing Commercial Viability, A "Symbiotic" Solution from the Perspective of Power Balance

- Core Viewpoint: Technological progress intensifies power concentration, requiring forced diffusion for checks and balances.

- Key Elements:

- Technology, automation, etc., strengthen economies of scale.

- The proliferation of proprietary technology hinders the natural diffusion of control.

- Diffusion must be forcibly promoted through policies, adversarial interoperability, etc.

- Market Impact: May drive the development of open-source, interoperable technologies, challenging monopolies.

- Timeliness Note: Long-term impact.

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Original Compilation: Saoirse, Foresight News

Many of us harbor fears about "Big Business." We appreciate the products and services companies provide, yet we recoil from the trillion-dollar monopolistic closed ecosystems, the quasi-gambling video games, and the corporations that manipulate entire governments for profit.

Many of us also fear "Big Government." We need police and courts to maintain public order and rely on the government for various public services, but we resent governments arbitrarily picking "winners" and "losers," restricting people's freedom of speech, freedom to read, and even freedom of thought, and we oppose governments violating human rights or waging wars.

Finally, many of us fear the third corner of this triangle: the "Big Mob." We recognize the value of an independent civil society, charities, and Wikipedia, but we detest mob lynchings, cancel culture, and extreme events like the French Revolution or the Taiping Rebellion.

At its core, we desire progress—whether technological, economic, or cultural—but we simultaneously fear the three primary historical forces that have driven this progress.

A common approach to resolving this dilemma is the concept of checks and balances. If society needs powerful forces to drive development, then these forces should check each other: either through internal balance within a single force (e.g., competition among businesses) or through checks between different forces, ideally both.

Historically, this balance largely emerged naturally: due to geographical constraints or the need to coordinate large-scale human efforts for global tasks, natural "diseconomies of scale" prevented excessive concentration of power. However, in this century, this dynamic no longer holds: the three forces mentioned are simultaneously becoming more powerful and inevitably interacting frequently.

In this article, I will delve into this theme and propose several strategies to protect the increasingly fragile "balance of power" characteristic of today's world.

In a previous blog post, I described this emerging world where "Big X" will persist long-term in all domains as a "dense jungle."

Why We Fear Big Government

People's fear of government is not without reason: governments possess coercive power and are fully capable of harming individuals. The power a government has to destroy an individual far exceeds anything Mark Zuckerberg or a cryptocurrency practitioner could ever hope to wield. This is why, for centuries, liberal political theory has centered on the core problem of "taming the leviathan"—enjoying the benefits of government maintaining law and order while avoiding the pitfalls of a "monarch who can arbitrarily dispose of subjects."

(Taming the leviathan: a political science concept referring to institutional designs like the rule of law, separation of powers, and decentralization to constrain the government—a "public power entity with strong coercive force that may infringe on individual rights"—ensuring its function of maintaining social order while preventing power abuse and balancing public order with individual freedom.)

This theoretical framework can be condensed into one sentence: government should be a "rule-maker," not a "player." That is, the government should strive to be a reliable "arena" that efficiently resolves interpersonal disputes within its jurisdiction, rather than an "actor" actively pursuing its own goals.

This ideal state can be approached in various ways:

- Libertarianism: Holds that the rules government should enforce are essentially only three—no fraud, no theft, no killing.

- Hayekian liberalism: Advocates avoiding central planning; if market intervention is necessary, it should specify goals rather than means, leaving implementation to market exploration.

- Civil libertarianism: Emphasizes freedom of speech, religion, and association, preventing government from imposing its preferences in cultural and ideological spheres.

- Rule of law: Government should clearly define "what is and is not allowed" through legislation, with courts responsible for enforcement.

- Common law supremacism: Advocates abolishing legislative bodies entirely, with a decentralized court system making rulings on individual cases, each forming a precedent that gradually evolves the law.

- Separation of powers: Divides government power into multiple branches that supervise and check each other.

- Subsidiarity principle: Holds that problems should be addressed by the lowest-level institution capable of handling them, minimizing centralization of decision-making.

- Multipolarity: At a minimum, avoid a single country dominating the globe; ideally, achieve two additional checks:

- Prevent any country from establishing excessive hegemony in its region;

- Ensure each individual has multiple "backup options" to choose from.

Even in governments not traditionally considered "liberal," similar logic applies. Recent research has found that among governments classified as "authoritarian," "institutionalized" governments often foster more economic growth than "personalized" ones.

Of course, completely preventing government from being a "player" is not always possible, especially when facing external conflict: if a "player" declares war on the "rules," the "player" will ultimately win. But even when government needs to temporarily act as a "player," its power is usually strictly limited—for example, the Roman "dictator" system: a dictator held immense power during emergencies, but once the crisis passed, power returned to normal.

Why We Fear Big Business

Criticism of corporations can be succinctly categorized into two types:

- Corporations are bad because they are "inherently evil";

- Corporations are bad because they are "soulless."

The root of the first problem (corporate "evil") lies in the fact that corporations are essentially efficient "goal-optimization machines," and as their capabilities and scale expand, the core goal of "profit maximization" increasingly diverges from the goals of users and society at large. This trend is visible in many industries: initially driven by enthusiasts, full of vitality, but over time becoming profit-oriented, eventually conflicting with user interests. For example:

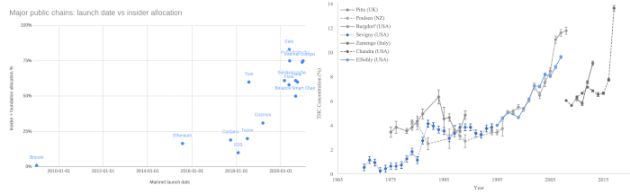

Left chart: Proportion of tokens directly allocated to insiders in newly issued cryptocurrencies during 2009-2021; Right chart: Concentration of THC (the psychoactive component) in cannabis during 1970-2020.

The video game industry exhibits the same trend: an area originally centered on "fun and achievement" now increasingly relies on built-in "slot machine mechanisms" to maximize extraction of funds from players. Even mainstream prediction markets are beginning to show worrying tendencies: shifting focus away from pro-social goals like "optimizing news media" or "improving governance" towards sports betting.

The above examples stem more from the combination of increased corporate capability and competitive pressure, while another category of examples relates directly to corporate scale expansion. Generally, the larger a corporation, the more capable it is of "distorting its surrounding environment" (including economic, political, cultural) to serve its interests. A corporation 10 times larger can gain 10 times the benefit from distorting the environment to a certain degree—therefore, it will engage in such behavior far more frequently than a small corporation, and when it acts, the resources deployed will be 10 times those of a small corporation.

Mathematically, this aligns with the logic of "why a monopoly sets price above marginal cost, increasing profit at the expense of social deadweight loss": in this scenario, the "market price" is the "environment" being distorted, and the monopoly "distorts the environment" by restricting supply. The strength of distortion capability is proportional to market share. But stated more generally, this logic applies to various scenarios, such as corporate lobbying, De Beers-style cultural manipulation campaigns, etc.

The second problem (corporate "soullessness") manifests as corporations becoming dull, rigid, risk-averse, and producing massive homogenized outcomes, both within and between corporations. (The homogenization of architectural styles is a typical manifestation of corporate "soullessness.")

Architectural homogenization is a classic form of corporate mediocrity.

The term "soulless" is interesting—its meaning lies between "evil" and "lifeless." It fits perfectly to describe corporations "making users addicted for clicks," "forming cartels to raise prices," or "polluting rivers." It also fits seamlessly to describe corporations "making global cityscapes uniform" or "producing 10 Hollywood movies with identical plots."

I believe both types of "soulless" phenomena stem from two factors: motivational homogeneity and institutional homogeneity. All corporations are highly driven by the "profit motive." If many powerful entities share the same strong motive and lack powerful countervailing forces, they will inevitably develop in the same direction.

"Institutional homogeneity" stems from corporate scale expansion: the larger the scale, the greater the incentive to "shape the environment." A $1 billion corporation will invest far more in "shaping the environment" than 100 $10 million corporations; simultaneously, scale expansion exacerbates homogenization—Starbucks contributes more to "urban homogenized atmosphere" than the sum of 100 competitors each 1% of its size.

Investors may exacerbate both trends. For a (non-sociopathic) startup founder, growing a company to $1 billion while benefiting the world might be more satisfying than growing it to $5 billion while harming society (after all, the yachts and planes $4.9 billion can buy are hardly worth being hated by the world). But investors are more distant from the "non-financial consequences" of their decisions: as market competition intensifies, investors willing to pursue $5 billion scale will achieve higher returns, while those content with $1 billion scale will get lower (or even negative) returns, struggling to attract capital. Furthermore, investors holding shares in multiple portfolio companies often passively push these companies to form, to some extent, a "merged super-entity." However, both trends face an important constraint: investors' "monitoring ability" and "accountability" regarding the internal affairs of portfolio companies are limited.

Meanwhile, market competition can alleviate "institutional homogeneity," but whether it alleviates "motivational homogeneity" depends on whether different competitors possess "differentiated, non-profit-oriented motives." In many cases, corporations do have such motives: for example, sacrificing short-term profit in the name of "publicly disclosing innovations," "adhering to core values," or "pursuing aesthetic value." But this is not inevitable.

If "motivational homogeneity" and "institutional homogeneity" lead to corporate "soullessness," then what is "soul"? I believe, in this context, "soul" is essentially diversity—the non-homogenized qualities between corporations.

Why We Fear the Big Mob

When people speak positively of "civil society"—the part of society that is neither profit-oriented nor governmental—they always describe it as "composed of numerous independent institutions, each focusing on different areas." If you ask an AI to explain "civil society," the examples it gives are largely the same.

When people criticize "populism," the opposite scenario often comes to mind: a charismatic leader inciting millions to follow them, forming a massive group pursuing a single goal. Populism, while flying the banner of "ordinary people," is more about constructing the illusion of "people united as one"—and this "unity" often manifests as support for a certain leader and opposition to a "hated external group."

Even when people criticize civil society, the argument always revolves around "it fails to fulfill its mission of 'numerous independent institutions each playing to their strengths,' instead promoting some spontaneously formed common agenda"—such as the phenomenon criticized by "The Cathedral" theory.

Balance Between Forces

In all the above cases, we discussed power balances within each of the three "forces." But different forces can also check each other, with the most typical case being the balance of power between government and business.

Capitalist democracy is essentially a theory of power balance between "Big Government" and "Big Business": entrepreneurs possess legal tools to challenge government overreach and gain independent action capability through capital concentration, while government can regulate businesses.

"Palladium-ism" admires billionaires, but specifically those who are "eccentric, taking unconventional actions to pursue their specific vision, rather than directly pursuing profit." From this perspective, "Palladium-ism" can be seen as an attempt to "capture the benefits of capitalism while avoiding its drawbacks."

Although both government and market created necessary conditions for the "Starship" project, what ultimately drove its birth was neither profit motive nor government directive.

My personal view on philanthropy is, in some aspects, similar to "Palladium-ism." I have explicitly supported billionaire philanthropy multiple times and hope more engage in it. But the philanthropy I advocate is philanthropy that "checks other social forces." Markets are often unwilling to fund public goods, and governments are often unwilling to fund projects that are "not yet elite consensus" or whose beneficiaries are not concentrated in a single country. Some projects fit both categories and are thus ignored by both market and government—and wealthy individuals can恰好 fill this gap.

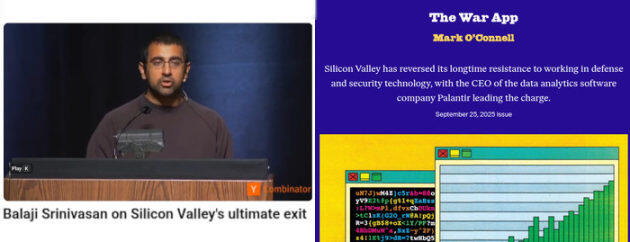

But billionaire philanthropy can also take a harmful direction: when it ceases to be a "checking force" on government and instead replaces government in wielding power. This has happened in Silicon Valley in recent years: powerful tech CEOs and venture capitalists have become less libertarian, less supportive of "exit," and more focused on directly pushing government towards their preferred goals—in exchange, they have made the world's most powerful government even stronger.

I prefer the scene on the left (2013) over the one on the right (2025): because the left embodies a balance of power, while the right shows two powerful factions that should check each other instead merging.

The other two pairs within the triangle can also form power balances. The Enlightenment-era concept of the "Fourth Estate" (the press) essentially positions civil society as a force checking government power (simultaneously, even without censorship, power flows the other way: government funding of primary, secondary schools, and universities profoundly influences educational content, especially in primary and secondary education). On the other hand, the media reports on business, and successful businesspeople fund the media. As long as there is no monopoly of power in a single direction, these mechanisms are healthy and enhance societal robustness.

Balance of Power and Economies of Scale

If one were to find an argument explaining both America's 20th-century rise and China's 21st-century development, the answer is simple: economies of scale. This is often used by Americans and Chinese to criticize Europe: Europe has many small-to-medium-sized countries with diverse cultures, languages, and institutions, making it difficult to cultivate pan-European large corporations; whereas in a large, culturally homogeneous country, corporations can easily scale to hundreds of millions of users.

The impact of economies of scale is crucial. For human development, we need economies of scale—because it is by far the most effective way to drive progress. But economies of scale are a double-edged sword: if my resources are twice yours, the progress I can achieve is more than double; therefore, by next year, my resources might be 2.02 times yours. Over time, the most powerful entity will eventually control everything.

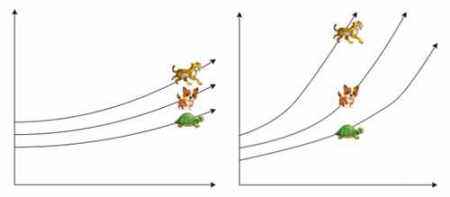

Left: Proportional growth—small initial differences remain small; Right: Growth under economies of scale—small initial differences become enormous over time.

Historically, two forces offset the effects of economies of scale, preventing power monopolies:

- Diseconomies of scale: Large institutions are inefficient in many ways, such as internal conflicts of interest, communication costs, costs from geographical distance, etc.

- Diffusion effects: When people move between companies or countries, they bring their ideas and skills; less developed countries can achieve "catch-up growth" through trade with developed ones; industrial espionage is ubiquitous, innovations are reverse-engineered; companies can use one social network to attract users to another.

If the "scale leader" is a cheetah and the "scale laggard" a tortoise, then "diseconomies of scale" slow the cheetah, while "diffusion effects" act like a rubber hand pulling the tortoise closer to the cheetah. But in recent years, several key forces are altering this balance:

- Rapid technological progress: Makes the "super-exponential growth curve" of economies of scale steeper than ever.

- Automation: Allows global tasks to be accomplished with few people, drastically reducing human coordination costs.

- Proliferation of proprietary technology: Modern society can produce proprietary software and hardware products that are "open for use but not for modification or control." Historically, delivering a product to consumers (whether domestically or across borders) necessarily meant allowing inspection and reverse engineering—but