Ethereum will undergo these major changes in 3 days.

- 核心观点:以太坊Fusaka硬分叉提升网络扩容与安全性。

- 关键要素:

- PeerDAS实现高效数据可用性采样。

- 多项EIP优化执行安全与Gas机制。

- 新增操作码与预编译增强开发兼容性。

- 市场影响:降低Layer2成本,提升以太坊可扩展性。

- 时效性标注:长期影响

Original text by Sahil Sojitra

Compiled by Odaily Planet Daily Golem ( @web3_golem )

The Fusaka hard fork, scheduled to activate on December 3, 2025, is another major network upgrade for Ethereum after Pectra, marking another significant step for the crypto giant toward scaling.

Pectra's upgraded EIP focuses on improving performance, security, and developer tools. Fusaka's upgraded EIP, on the other hand, emphasizes scaling, opcode updates, and execution security.

PeerDAS (EIP-7594) improves data availability by allowing nodes to verify blobs without downloading all the data. Several upgrades also enhance execution security, including limiting ModExp (EIP-7823), limiting transaction gas limits (EIP-7825), and updating ModExp gas costs (EIP-7883). This Fusaka upgrade also improves block generation through a deterministic proposer lookahead mechanism (EIP-7917) and maintains stable blob fees by setting a "reservation price" linked to execution costs (EIP-7918).

Other enhancements include limiting the block size of the RLP format (EIP-7934), adding a new CLZ opcode to speed up bit operations (EIP-7939), and introducing the secp256r1 pre-compilation (EIP-7951) for better compatibility with modern cryptography and hardware security keys.

Fusaka is a combined name for Fulu (the execution layer) and Osaka (the consensus layer). It represents another step forward for Ethereum towards a highly scalable, data-rich future where Layer 2 Rollups can operate at lower costs and faster speeds.

This article will provide an in-depth analysis of the nine core EIP proposals of the Fusaka hard fork.

EIP-7594: PeerDAS — Node Data Availability Sampling

Ethereum needs this proposal because the network wants to provide greater data availability for users, especially Rollup users.

However, under the current EIP-4844 design, each node still needs to download a large amount of blob data to verify whether it has been published. This causes scalability issues because if all nodes have to download all the data, the network's bandwidth and hardware requirements increase, and the degree of decentralization is affected. To solve this problem, Ethereum needs a way to allow nodes to confirm the availability of data without downloading all of it.

Data Availability Sampling (DAS) addresses this issue by allowing nodes to examine only a small amount of random data.

However, Ethereum also needs a DAS method that is compatible with the existing Gossip network and does not impose a heavy computational burden on block producers. PeerDAS was created to meet these needs and safely increase blob throughput while keeping node requirements low.

PeerDAS is a network system that allows nodes to download only small fragments of data to verify whether the complete data has been published. Instead of downloading the entire data, nodes utilize regular gossip network sharing to discover which nodes hold a specific portion of the data and request only the necessary small sample. The core idea is that by downloading only a random small portion of a data fragment, a node can still be certain of the existence of the entire fragment. For example, a node might download only about 1/8 of the data instead of the complete 256 KB fragment—but because many nodes will sample different parts, any missing data will be quickly detected.

To achieve sampling, PeerDAS uses a basic erasure coding method to expand each data segment in EIP-4844. Erasure coding is a technique that adds extra redundant data so that the original data can be recovered even if some data segments are missing—similar to a jigsaw puzzle that can be put together even if some pieces are missing.

The blob is transformed into a "row" containing the original data along with some additional encoded data to allow for subsequent data reconstruction. This row is then divided into smaller pieces called "cells," which are the smallest verification units associated with a KZG commitment. All "rows" are subsequently reorganized into "columns," each containing cells from the same positions across all rows. Each column is assigned to a specific gossip subnet.

Each node is responsible for storing certain columns based on its node ID and sampling some columns from its peers in each time slot. If a node collects at least 50% of the columns, it can fully reconstruct the data. If it collects less than 50%, it needs to request the missing columns from its peers. This ensures that if the data has indeed been published, it can always be reconstructed. In short, if there are a total of 64 columns, a node only needs approximately 32 columns to reconstruct a complete blob. It retains some columns itself and downloads others from its peers. As long as half of the columns are present in the network, a node can reconstruct everything, even if some columns are missing.

Furthermore, EIP-7594 introduces an important rule: no transaction can contain more than 6 blobs. This restriction must be enforced during transaction verification, gossip propagation, block creation, and block processing. This helps reduce the extreme case where a single transaction can overload the blob system.

PeerDAS has added a feature called "cell KZG proof." A cell KZG proof demonstrates that a KZG commitment does indeed match a specific cell (a small unit) in the blob. This allows nodes to download only the cells they want to sample. Obtaining the complete blob while ensuring data integrity is crucial for data availability sampling.

However, generating all these unit proofs is costly. Block producers need to repeatedly compute these proofs over many blobs, which is too slow. However, the cost of proof verification is very low; therefore, EIP-7594 requires blob transaction senders to pre-generate all unit proofs and include them in the transaction wrapper.

For this reason, the transaction gossip (PooledTransactions) now uses a modified wrapper:

rlp([tx_payload_body, wrapper_version, blobs, commitments, cell_proofs])

In the new wrapper, `cell_proofs` is simply a list containing all proofs for each cell of each blob (e.g., `[cell_proof_0, cell_proof_1, ...]`). The other fields `tx_payload_body`, `blobs`, and `commitments` are identical to those in EIP-4844. The difference is that the original single "proofs" field has been removed and replaced with a new list of `cell_proofs`, and a new field called `wrapper_version` has been added to indicate the currently used wrapper format.

PeerDAS enables Ethereum to improve data availability without increasing node workload . Currently, a node only needs to sample approximately 1/8 of the total data. In the future, this proportion could even drop to 1/16 or 1/32, thus improving Ethereum's scalability. The system works well because each node has numerous peers, so if a peer cannot provide the required data, the node can request it from other peers. This naturally establishes redundancy and improves security. Nodes can also choose to store more data than actually needed, further enhancing network security.

Validator nodes bear more responsibility than regular full nodes. Because validator nodes run on more powerful hardware, PeerDAS allocates a corresponding data hosting load to them based on the total number of validator nodes. This ensures that there is always a stable group of nodes available to store and share more data, thereby improving network reliability. In short, if there are 900,000 validator nodes, each validator node may be allocated a small portion of the total data for storage and servicing. Because validator nodes have more powerful machines, the network can trust them to ensure data availability.

PeerDAS uses column sampling instead of row sampling because this greatly simplifies data reconstruction. If a node samples an entire row (the whole blob), it would require creating an extra "extended blob" that wouldn't have existed originally, which would slow down block producers.

Column sampling allows nodes to pre-prepare additional row data, and the necessary proofs are computed by the transaction sender (rather than the block producer). This maintains the speed and efficiency of block creation. For example, suppose a blob is a 4x4 grid of cells. Row sampling means taking all four cells from a row, but some extended rows are not yet ready, so the block producer must generate them on-the-spot; column sampling, on the other hand, extracts one cell from each row (each column), and the additional cells needed for reconstruction can be pre-prepared, allowing nodes to verify data without slowing down block generation.

EIP-7594 is fully compatible with EIP-4844, so it will not break any existing functionality on Ethereum. All tests and detailed rules are included in the consensus and enforcement specifications.

The primary security risk of any DAS system is a "data concealment attack," where a block producer pretends the data is available but actually hides parts of it. PeerDAS prevents this by using random sampling: nodes inspect random portions of the data. The more nodes sampled, the harder it is for an attacker to cheat. EIP-7594 even provides a formula to calculate the probability of such an attack succeeding based on the total number of nodes (n), the total number of samples (m), and the number of samples per node (k). On the Ethereum mainnet, with approximately 10,000 nodes, the probability of a successful attack is extremely low, therefore PeerDAS is considered secure.

EIP-7823: Sets the maximum size of 1024 bytes for MODEXP

The necessity of this proposal lies in the fact that Ethereum's current MODEXP pre-compilation mechanism has led to numerous consensus vulnerabilities over the years. These vulnerabilities largely stem from MODEXP's allowance of extremely large and impractical amounts of input data, forcing clients to handle countless exceptions.

Because each node must process all inputs provided by a transaction, the lack of an upper limit makes MODEXP more difficult to test, more prone to errors, and more likely to behave differently on different clients. The excessively large input data also makes gas cost formulas difficult to predict, as pricing becomes challenging when the data volume can grow indefinitely. These issues also make it difficult to replace MODEXP with EVM-level code using tools like EVMMAX in the future, because without fixed constraints, developers cannot create safe and optimized execution paths.

To mitigate these issues and improve Ethereum's stability, EIP-7823 adds a strict cap on the amount of MODEXP input data, making the pre-compilation process more secure, easier to test, and more predictable.

EIP-7823 introduces a simple rule: all three length fields used by MODEXP (base, exponent, and modulus) must be less than or equal to 8192 bits, or 1024 bytes. MODEXP input follows the format defined in EIP-198: <len(BASE)> <len(EXPONENT)> <len(MODULUS)> <BASE> <EXPONENT> <MODULUS>, therefore this EIP only restricts the length values. If any length exceeds 1024 bytes, preprocessing will immediately stop, return an error, and consume all gas.

For example, if someone tries to provide a 2000-byte radix, the call will fail before any work begins. These limits still satisfy all practical application scenarios. RSA verification typically uses key lengths of 1024 bits, 2048 bits, or 4096 bits, all of which are within the new limits. Elliptic curve operations use smaller input sizes, typically less than 384 bits, and are therefore unaffected.

These new limitations also facilitate future upgrades. If MODEXP is rewritten as EVM code using EVMMAX in the future, developers can add optimized paths for common input sizes (such as 256-bit, 381-bit, or 2048-bit) and use slower fallback schemes for rare cases. By fixing the maximum input size, developers can even add special handling for very common moduli. Previously, this was not possible because the input size was unlimited, resulting in an excessively large and unsafely manageable design space.

To confirm that this change would not disrupt past transactions, the authors analyzed all MODEXP usage from block 5,472,266 (April 20, 2018) to block 21,550,926 (January 4, 2025). The results showed that none of the historically successful MODEXP calls used more than 513 bytes of input, well below the new 1024-byte limit. Most actual calls used smaller lengths, such as 32 bytes, 128 bytes, or 256 bytes.

There are some invalid or corrupted calls, such as empty input, input padded with duplicate bytes, and a very large but invalid input. These calls also behave invalidly under the new restrictions because they are invalid in themselves. Therefore, while EIP-7823 is a significant technical change, it does not actually alter the outcome of any past transactions.

From a security perspective, reducing the allowed input size does not introduce new risks. Instead, it eliminates unnecessary extreme cases that previously led to errors and inconsistencies between clients. By limiting the MODEXP input to a reasonable range, EIP-7823 makes the system more predictable, reduces strange extreme cases, and lowers the probability of errors between different implementations. These limitations also help prepare for a smoother transition should future upgrades (such as EVMMAX) introduce optimized execution paths.

EIP-7825: Transaction limit of 16.7 million Gas

Ethereum does indeed need this proposal, because currently a single transaction can almost consume the entire block's gas limit.

This causes several problems: a single transaction may consume most of the block's resources, leading to slow delays similar to a DoS attack; operations that consume a lot of gas will increase Ethereum's state updates too quickly; and block verification speed will slow down, making it difficult for nodes to keep up.

If a user submits a massive transaction that consumes almost all of the gas (e.g., a transaction that consumes 38 million gas in a 40 million gas block), then other ordinary transactions cannot be included in that block, and each node must spend extra time validating the block. This threatens the stability and decentralization of the network, as slower validation means weaker nodes will fall behind. To address this issue, Ethereum needs a secure gas cap to limit the amount of gas a single transaction can use, thereby making block load more predictable, reducing the risk of DoS attacks, and making the load on nodes more balanced.

EIP-7825 introduces a hard rule: any transaction must not consume more than 16,777,216 (2²⁴) Gas. This becomes a protocol-level cap, meaning it applies to all stages: users sending transactions, transaction pools checking transactions, and validators packaging transactions into blocks. If someone sends more Gas than this limit, the client must immediately reject the transaction and return an error like MAX_GAS_LIMIT_EXCEEDED.

This limit is completely independent of the block gas limit. For example, even if the block gas limit is 40 million, the gas consumption of any single transaction must not exceed 16.7 million. The purpose is to ensure that each block can accommodate multiple transactions, rather than allowing a single transaction to occupy the entire block.

To better understand this, suppose a block can hold 40 million Gas. Without this limit, someone could send a transaction that consumes 35 million to 40 million Gas. This transaction would monopolize the block, leaving no room for other transactions, much like someone chartering an entire bus, preventing anyone else from boarding. The new 16.7 million Gas limit will allow blocks to naturally accommodate multiple transactions, thus preventing such abuse.

The proposal also sets forth specific requirements for how clients should verify transactions. If a transaction's gas exceeds 16,777,216, the transaction pool must reject it, meaning such transactions won't even be queued. During block verification, if a block contains transactions exceeding the limit, the block itself must be rejected.

The number 16,777,216 (2²⁴) was chosen because it represents a clear power of 2 boundary, making it easy to implement, and it's still large enough to handle most real-world transactions, such as smart contract deployments, complex DeFi interactions, or multi-step contract calls. This value is approximately half the typical block size, meaning even the most complex transactions can be easily kept within this limit.

This EIP also maintains compatibility with existing gas mechanisms. Most users will not notice this change because almost all existing transactions consume well below 16 million gas. Validators and block creators can still create blocks with a total gas exceeding 16.7 million, as long as each transaction adheres to the new cap.

The only affected transactions are those that previously attempted to exceed the new limits and became extremely large. These transactions must now be broken down into multiple smaller operations, similar to splitting a very large file upload into two smaller files. Technically, this change is not backward compatible with these rare, extreme transactions, but the number of users affected is expected to be very small.

In terms of security, the gas cap makes Ethereum more resistant to gas-based DoS attacks because attackers can no longer force validators to process extremely large transactions. It also helps maintain the predictability of block validation times, making it easier for nodes to stay synchronized. The main extreme case is that a few very large contract deployments may not be able to meet the cap requirements, necessitating redesign or splitting into multiple deployment steps.

Overall, EIP-7825 aims to strengthen network protection against abuse, maintain reasonable node demand, improve the fairness of block space usage, and ensure that the blockchain can still operate quickly and stably as the gas cap increases.

EIP-7883: ModExp Gas Rates Increase

Ethereum needs this proposal because the price of ModExp pre-compiled (used for modular exponentiation) has consistently been low compared to the resources it actually consumes.

In some cases, the computational demands of a ModExp operation far exceed the fees users currently pay. This mismatch poses a risk: if complex ModExp calls are priced too low, they could become bottlenecks, making it difficult for the network to safely increase gas limits. This is because block producers might be forced to handle extremely heavy operations at very low costs.

To address this issue, Ethereum needed to adjust the ModExp pricing formula so that gas consumption accurately reflects the amount of work actually performed by the client. Therefore, EIP-7883 introduced new rules that increased the minimum gas cost, increased the total gas cost, and made operations with large input data volumes (especially exponentiation, base, or modulo operations exceeding 32 bytes) more expensive, thus matching gas pricing to the actual computational demands.

The proposal increases costs in several key ways, thereby modifying the ModExp pricing algorithm originally defined in EIP-2565.

First, the minimum gas consumption has increased from 200 to 500, and the total gas consumption is no longer divided by 3, meaning the total gas consumption has effectively tripled. For example, if a ModExp call previously consumed 1200 gas, it will now consume approximately 3600 gas under the new formula.

Secondly, the computational cost doubles for exponents longer than 32 bytes because the multiplier increases from 8 to 16. For example, if the exponent length is 40 bytes, EIP-2565 would increase the number of iterations by 8 × (40 − 32) = 64, while EIP-7883 now uses 16 × (40 − 32) = 128, doubling the cost.

Third, pricing now assumes a minimum radix/modulus size of 32 bytes, and computational costs increase dramatically as these values exceed 32 bytes. For example, if the modulus is 64 bytes, the new rule applies double the complexity (2 × words²) instead of the previous simpler formula, thus reflecting the actual cost of large number operations. These changes collectively ensure that small ModExp operations pay a reasonable minimum fee, and that the cost of large, complex operations is adjusted appropriately according to their size.

This proposal defines a new Gas calculation function and updates the rules for complexity and iteration count. The multiplication complexity now uses a default value of 16 for base/modulus lengths of 32 bytes or less, while for larger inputs, it switches to the more complex formula 2 × words², where "words" refers to the number of 8-byte blocks. The iteration count has also been updated so that exponents of 32 bytes or less use their bit length to determine complexity, while exponents greater than 32 bytes incur a larger Gas penalty.

This ensures that very large exponents, which are computationally expensive, now have higher gas costs. Importantly, the minimum returned gas cost is now forced to 500 instead of the previous 200, making even the simplest ModExp call more reasonable.

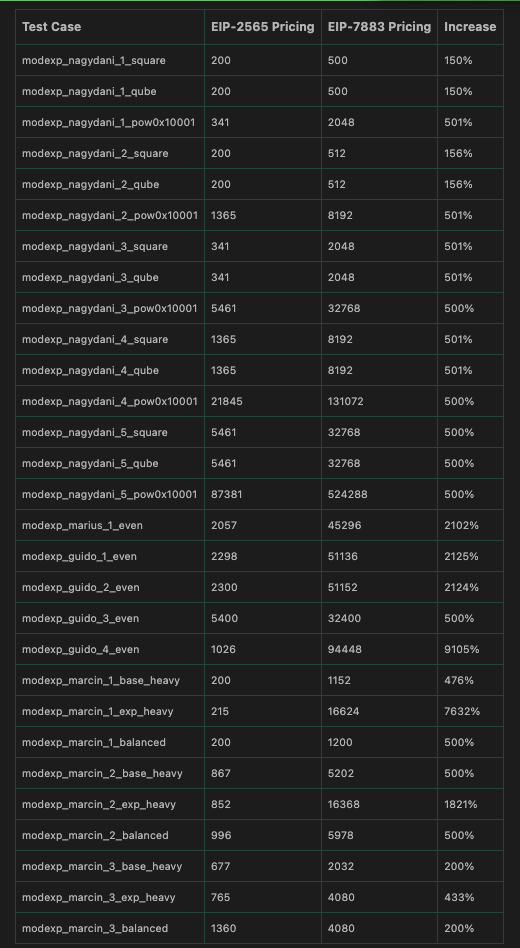

These price increases are motivated by benchmark tests that show ModExp pre-compiled pricing is significantly undervalued in many cases. The revised formula increases gas costs by 150% for small operations, about 200% for typical operations, and many times more, sometimes exceeding 80 times, for large or unbalanced operations, depending on the size of the exponent, base, or modulus .

The purpose of this move is not to change how ModExp works, but to ensure that even under extreme resource-intensive conditions, it will no longer threaten network stability or hinder future increases in the block gas cap. Because EIP-7883 changes the number of gas required for ModExp, it is not backward compatible, but gas repricing has occurred multiple times in Ethereum and is well understood.

Test results show that the increase in gas costs is significant. Approximately 99.69% of historical ModExp calls now require either 500 Gas (previously 200 Gas) or three times the previous price. However, the increase in gas costs is even greater for some high-load test cases. For example, in an "exponential computationally intensive" test, gas consumption jumped from 215 to 16,624, an increase of approximately 76 times, because pricing for extremely high exponents is now more reasonable.

In terms of security, this proposal does not introduce new attack vectors, nor does it reduce the cost of any computations. Instead, it focuses on mitigating a significant risk: excessively low-priced ModExp operations could allow attackers to fill blocks with extremely computationally intensive computations at very low cost. The only potential drawback is that some ModExp operations might become too expensive, but this is far better than the current problem of excessively low pricing. The proposal does not introduce any interface changes or new features, so existing arithmetic behavior and test vectors remain valid.

EIP-7917: Accurately Predicting the Next Proposer

Ethereum needs this proposal because the schedule of proposers for the next epoch of the network cannot be fully predicted. Even if the RANDAO seed for the N+1th epoch is known in the Nth epoch, the actual list of proposers may still change due to updates to the effective balance (EB) within the Nth epoch.

These EB changes can stem from slashings, penalties, rewards exceeding 1 ETH, validator consolidation, or new deposits, especially after EIP-7251 increased the maximum effective balance to over 32 ETH. This uncertainty poses problems for systems that rely on knowing the next proposer in advance (such as pre-confirmed protocols), which require stable and predictable timelines to function smoothly. Validators might even attempt to "pump" or manipulate their effective balance to influence the proposer of the next epoch.

Because of these issues, Ethereum needs a way to make the proposer timeline fully deterministic over the next few epochs, so that it won't change due to last-minute EB updates, and is easily accessible to the application layer.

To achieve this, EIP-7917 introduces a deterministic proposer lookahead mechanism, which pre-computes and stores the proposer schedule for the next MIN_SEED_LOOKAHEAD + 1 epochs at the start of each epoch. Simply put, the beacon state now contains a list called `prosoperer_lookahead`, which always covers proposers for two full cycles (a total of 64 slots).

For example, when epoch N begins, the list already contains proposers for each slot in epoch N and epoch N+1. Then, when the network enters epoch N+1, the list is shifted forward: the proposer entry for epoch N is removed, the entry for epoch N+1 is moved to the front of the list, and a new proposer entry for epoch N+2 is added to the end of the list. This makes the scheduling fixed and predictable, and clients can read it directly without recalculating proposers for each slot.

To keep the list up-to-date, it moves forward at each epoch boundary: data from the previous epoch is removed, and a new set of proposer indices for the next future epoch is calculated and added to the list. This process uses the same seed and effective balance rules as before, but the scheduling is now calculated earlier, thus avoiding the impact of effective balance changes after the seed is determined. The first block after the fork also populates the entire lookahead range to ensure that all future epochs have correctly initialized scheduling.

Let's assume there are 8 slots per epoch instead of 32 (for simplicity). Without this EIP, during the 5th epoch, even though you know the seed for the 6th epoch, the actual proposer for slot 2 in the 6th epoch could still change if a validator is penalized or receives enough reward to alter their effective balance during the 5th epoch. With EIP-7917, Ethereum pre-computes all proposers for the 5th, 6th, and 7th epochs at the start of the 5th epoch and stores them sequentially in `prosopers_lookahead`. Therefore, even if the balance changes later in the 5th epoch, the list of proposers for the 6th epoch remains fixed and predictable.

EIP-7917 addresses a long-standing flaw in the Beacon Chain design. It guarantees that once the RANDAO of a previous epoch is available, the validator selection for future epochs cannot be changed. This also prevents "effective balance scrambling," where validators attempt to adjust their balances after seeing the RANDAO to influence the proposer list for the next epoch. This deterministic look-ahead mechanism eliminates the entire attack vector, significantly simplifying security analysis. It also allows consensus clients to know in advance who will propose upcoming blocks, which facilitates implementation and allows application layers to easily verify the proposer schedule via Merkle proofs of the beacon root.

Prior to this proposal, clients only computed the proposers for the current time slot. With EIP-7917, they now compute the list of proposers for all time slots of the next epoch all at once during each epoch transition. This adds a small amount of work, but computing the proposer index is very lightweight, mainly involving sampling the list of validators using a seed. However, clients need to benchmark to ensure that this additional computation does not cause performance issues.

EIP-7918: Blob base fees are limited by execution costs.

Ethereum needs this proposal because the current Blob fee system (derived from EIP-4844) fails when gas becomes the main cost of rolling.

Currently, the execution gas (the cost of including a Blob transaction in a block) paid by most Rollups is far higher than the actual Blob fee. This creates a problem: even as Ethereum continuously reduces the base Blob fee, the total cost of a Rollup doesn't actually change because the highest cost remains the execution gas. Therefore, the base Blob fee will continue to decrease until it reaches an absolute minimum (1 wei), at which point the protocol can no longer use Blob fees to control demand. Then, when Blob usage suddenly surges, the Blob fee takes many blocks to recover to normal levels. This makes prices unstable and unpredictable for users.

For example, suppose a Rollup wants to publish its data: it needs to pay approximately 25,000,000 gwei in execution gas (approximately 1,000,000 gas requires 25 gwei), while the Blob fee is only about 200 gwei. This means the total cost is approximately 25,000,200 gwei, with almost all of the cost coming from execution gas, not the Blob fee. If Ethereum continues to reduce the Blob fee, for example from 200 gwei to 50 gwei, then to 10 gwei, and finally to 1 gwei, the total cost will hardly change, remaining at 25,000,000 gwei.

EIP-7918 addresses this issue by introducing a minimum “reservation price” based on execution base costs, thereby preventing Blob prices from becoming too low and making Rollup’s Blob pricing more stable and predictable.

The core idea of EIP-7918 is simple: the price of a blob should never be lower than a certain amount of execution gas cost (called BLOB_BASE_COST). The value of calc_excess_blob_gas() is set to 2¹³, and this mechanism is implemented by making a small modification to the calc_excess_blob_gas() function.

Typically, this function increases or decreases the Blob base fee based on whether the blob gas used by the block is above or below a target value. Under this proposal, if the blob becomes "too low" relative to the execution gas, the function will stop deducting the target blob gas. This allows excess blob gas to grow more rapidly, preventing the Blob base fee from decreasing further. Therefore, the Blob base fee now has a minimum value, equal to BLOB_BASE_COST × base_fee_per_gas ÷ GAS_PER_BLOB.

To understand why this is necessary, let's look at the demand for blobs. Rollups focus on the total cost they pay: execution cost plus blob cost. If the execution gas cost is very high, say 20 gwei, then even if the blob cost drops from 2 gwei to 0.2 gwei, the total cost remains almost unchanged. This means that reducing the base cost of a blob has almost no impact on demand. In economics, this is called "cost inelasticity." It creates a situation where the demand curve is almost vertical: lowering the price does not increase demand.

In this scenario, the Blob base fee mechanism becomes blind—it continues to lower the price even when demand doesn't respond. This is why the blob base fee often drops to 1 gwei. Then, when actual demand increases later, the protocol needs an hour or more of nearly full blocks to raise the fee to a reasonable level. EIP-7918 addresses this issue by establishing a reserve price linked to execution gas, ensuring that the Blob fee remains meaningful even when execution costs dominate.

Another reason for adding this reservation price is that nodes need to do a lot of extra work to verify the KZG proofs of the blob data. These proofs guarantee that the data in the blob matches its promise. Under EIP-4844, nodes only need to verify one proof for each blob, which is inexpensive. However, in EIP-7918, nodes need to verify a much larger number of proofs. This is entirely because in EIP-7594 (PeerDAS), blobs are divided into many small pieces called cells, each with its own proof, which significantly increases the verification workload.

In the long run, EIP-7918 also helps Ethereum prepare for the future. As technology advances, the cost of storing and sharing data will naturally decrease, and Ethereum is expected to allow for the storage of more Blob data over time. As Blob capacity increases, Blob fees (in ETH) will naturally decrease. This proposal supports this because the retention price is pegged to the execution gas price, rather than a fixed value, so it can adjust as the network grows.

As the Blob space and execution block space expand, their price relationship will remain balanced. Only in rare cases, where Ethereum significantly increases Blob capacity without increasing execution gas capacity, could the reserve price become excessively high. In such a scenario, Blob fees could ultimately exceed actual needs. However, Ethereum has no plans to expand in this way—Blob space and execution block space are expected to grow in tandem. Therefore, the chosen value (BLOB_BASE_COST = 2¹³) is considered safe and balanced.

When execution gas fees suddenly spike, there's a small detail to be aware of. Since the price of a blob depends on the base execution cost, a sudden increase in execution costs can temporarily put the blob fee into a state dominated by execution costs. For example, suppose the execution gas fee suddenly jumps from 20 gwei to 60 gwei within a block. Because the price of a blob is pegged to this value, the blob fee cannot fall below the new higher level. If the blob is still being used, its fee will continue to grow normally, but the protocol won't allow it to decrease until it grows sufficiently to match the higher execution costs. This means that within a few blocks, the blob fee may grow slower than the execution cost. This temporary delay is harmless—it actually prevents drastic fluctuations in the blob price and makes the system smoother.

The authors also conducted an empirical analysis of actual block transaction activity from November 2024 to March 2025, applying the reserve price rule. During periods of high execution fees (averaging approximately 16 gwei), the reserve threshold significantly increased the base block fee compared to the old mechanism. During periods of low execution fees (averaging approximately 1.3 gwei), block fees remained almost constant unless the calculated base block fee was lower than the reserve price. By comparing thousands of blocks, the authors show that the new mechanism creates more stable pricing while maintaining a natural response to demand. The block fee histogram for four months shows that the reserve price prevents block fees from plummeting to 1 gwei, thus reducing extreme volatility.

In terms of security, this change does not introduce any risk. The base block fee will always be equal to or higher than the BLOB_BASE_COST unit cost of executing gas. This is safe because the mechanism only raises the minimum fee, and setting a price floor does not affect the correctness of the protocol. It simply ensures healthy economic operation.

EIP-7934: RLP enforces block size limits

Prior to EIP-7934, Ethereum did not have a strict upper limit on the size of execution blocks encoded with RLP. Theoretically, if a block contained a large number of transactions or very complex data, its size could be extremely large. This caused two main problems: network instability and the risk of denial-of-service (DoS) attacks.

If a block is too large, it will take longer for nodes to download and verify it, slowing down block propagation and increasing the likelihood of temporary blockchain forks. Worse still, an attacker could intentionally create an extremely large block to overload nodes, causing delays or even taking them offline—a classic denial-of-service attack. Furthermore, Ethereum's consensus layer (CL) Gossip protocol already refuses to propagate any block larger than 10MB, meaning that excessively large execution blocks may fail to propagate through the network, causing on-chain fragmentation or disagreements between nodes. Given these risks, Ethereum needs a clear protocol-level rule to prevent excessively large blocks and maintain network stability and security.

EIP-7934 addresses this issue by introducing a protocol-level RLP encoding to enforce a block size cap. The maximum allowed block size (MAX_BLOCK_SIZE) is set to 10 MiB (10,485,760 bytes), but Ethereum adds 2 MiB (2,097,152 bytes) to this limit because beacon blocks also occupy some space (SAFETY_MARGIN).

This means the maximum allowed RLP encoded block size is MAX_RLP_BLOCK_SIZE = MAX_BLOCK_SIZE - SAFETY_MARGIN. If the encoded block exceeds this limit, it will be considered invalid, and the node must reject it. With this rule, block producers must check the encoded size of each block they build, and validators must verify this limit during block verification. This size cap is independent of the gas limit, meaning that even if a block is "below the gas limit," it will still be rejected if its encoded size is too large. This ensures that both gas usage and actual byte size limits are met.

The choice of a 10 MiB cap is intentional because it aligns with existing limits in the consensus layer's gossip protocol. Any data larger than 10 MiB will not be broadcast across the network, thus this EIP keeps the execution layer consistent with the consensus layer's limits. This ensures consistency across all components and prevents valid executed blocks from becoming "invisible" due to CL refusing to propagate.

This change is not backward compatible with blocks larger than the new limit, meaning miners and validators must update their clients to comply with the rule. However, since oversized blocks are inherently problematic and not common in practice, the impact is minimal.

In terms of security, EIP-7934 significantly enhances Ethereum's ability to resist DoS attacks targeting specific block sizes by ensuring that no participant can create blocks that would cripple the network. In summary, EIP-7934 adds an important security boundary, improves stability, standardizes the behavior of the Execution Logic (EL) and CL, and prevents various attacks related to the creation and propagation of oversized blocks.

EIP-7939: Calculate Leading Zeros (CLZ) Opcode

Prior to this EIP, Ethereum lacked built-in opcodes to calculate the number of leading zeros in a 256-bit number. Developers had to manually implement the CLZ function using Solidity, which required numerous bitwise operations and comparisons.

This is a significant problem because custom implementations are slow, costly, and consume a large amount of bytecode, increasing Gas consumption. For zero-knowledge proof systems, the cost is even higher; the proof cost of right-shift operations is extremely high, so operations like CLZ significantly slow down zero-knowledge proof circuits. Since CLZ is a very common low-level function widely used in mathematical libraries, compression algorithms, bitmaps, signature schemes, and many cryptographic or data processing tasks, Ethereum needs a faster and more economical computational method.

EIP-7939 addresses this issue by introducing a new opcode called CLZ (0x1e). This opcode reads a 256-bit value from the stack and returns the number of leading zeros. If the input number is zero, the opcode returns 256 because a 256-bit zero has 256 leading zeros.

This is consistent with how CLZ works in many CPU architectures such as ARM and x86, where CLZ operations are natively supported. Adding CLZ can significantly reduce the overhead of many algorithms: operations such as lnWad, powWad, LambertW, various mathematical functions, byte string comparisons, bitmap scans, data compression/decompression calls, and post-quantum signature schemes can all benefit from faster zero-lookahead detection.

CLZ's gas cost is set at 5, similar to ADD, and slightly higher than the previous MUL price, to avoid the risk of denial-of-service (DoS) attacks due to underpricing. Benchmarks show that CLZ's computational cost is roughly the same as ADD's, and in the SP1 rv32im proof environment, CLZ's proof cost is actually lower than ADD's, thus reducing the cost of zero-knowledge proofs.

EIP-7939 is fully backward compatible because it introduces a new opcode and does not modify any existing behavior.

Overall, EIP-7939 makes Ethereum faster, cheaper, and more developer-friendly by adding a simple and efficient primitive that is already supported by modern CPUs—reducing gas fees, decreasing bytecode size, and lowering the cost of zero-knowledge proofs for many common operations.

EIP-7951: Supports signatures for modern hardware.

Prior to this EIP, Ethereum lacked a secure, native way to verify digital signatures created using the secp256r1 (P-256) curve.

This curve is the standard used by modern devices such as Apple Secure Enclave, Android Keystore, HSM, TEE, and FIDO2/WebAuthn security keys. Without this support, applications and wallets cannot easily perform signatures using device-level hardware security. A previous attempt (RIP-7212) had two serious security vulnerabilities, related to infinity point handling and incorrect signature comparisons. These issues could lead to verification errors and even consensus failures. EIP-7951 addresses these security issues and introduces a secure, native pre-compiled protocol, finally enabling Ethereum to securely and efficiently support signatures from modern hardware.

EIP-7951 adds a new pre-compiled contract named P256VERIFY at address 0x100, which performs ECDSA signature verification using the secp256r1 curve. This makes signature verification faster and less expensive compared to implementing the algorithm directly in Solidity.

EIP-7951 also defines strict input validation rules. If any invalid case exists, the pre-compilation will return failure without rollback, consuming the same gas as a successful call. The validation algorithm follows standard ECDSA: it calculates s⁻¹ mod n, reconstructs the signature point R', rejects it if R' is at infinity, and finally checks if the x-coordinate of R' matches r (mod n). This corrects an error in RIP-7212, which directly compares r' instead of first simplifying it modulo n.

The gas fee for this operation is set at 6900 gas, higher than the RIP-7212 version, but consistent with the actual performance benchmark verified by secp256r1. Importantly, the interface is fully compatible with Layer 2 networks that have already deployed RIP-7212 (same address, same input/output format), so existing smart contracts will continue to function normally without any changes. The only differences are the revised behavior and the higher gas fee.

From a security perspective, EIP-7951 restores the correct behavior of ECDSA, eliminates the plasticity issues at the pre-compiled level (leaving optional checks to the application), and explicitly states that pre-compilation does not require constant-time execution. The secp256r1 curve provides 128-bit security and has gained widespread trust and analysis, making it safe for use on Ethereum.

In short, EIP-7951 aims to securely bring modern hardware-supported authentication to Ethereum, fix security issues in earlier proposals, and provide a reliable, standardized way to verify P-256 signatures across the ecosystem.

Summarize

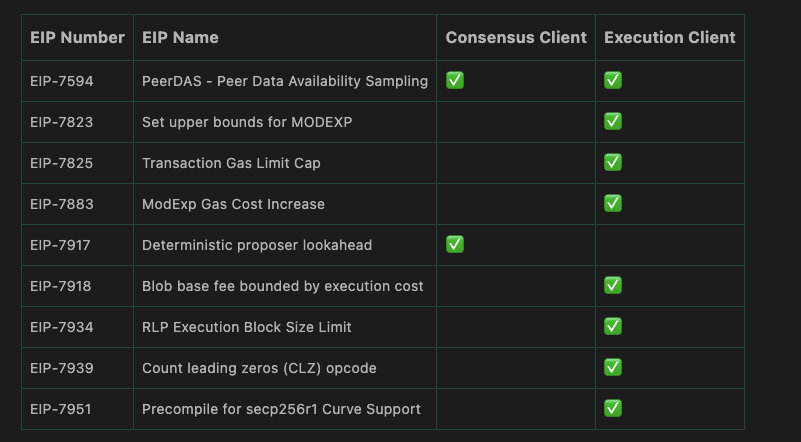

The table below summarizes which Ethereum clients require changes for different Fusaka EIPs. A checkmark under "Consensus Client" indicates that the EIP needs to update its consensus layer client, while a checkmark under "Execution Client" indicates that the upgrade affects the execution layer client. Some EIPs require updates to both the consensus and execution layers, while others only require updates to one of them.

In summary, these are the key EIPs included in the Fusaka hard fork. While this upgrade involves several improvements to consensus and execution clients, from gas adjustments and opcode updates to new pre-compiled versions, the core of this upgrade remains PeerDAS, which introduces peer-to-peer data availability sampling, enabling more efficient and decentralized processing of Blob data across the network.