Concept-driven or data-driven? Vitalik's new article offers in-depth reflections on blockchain decision-making.

- 核心观点:理念驱动与数据驱动需平衡。

- 关键要素:

- 理念驱动提升社区凝聚力。

- 数据驱动确保决策理性。

- 分工协作需不同目标。

- 市场影响:促进行业决策更稳健。

- 时效性标注:长期影响。

Original Article | Vitalik Buterin

Compiled by Odaily Planet Daily ( @OdailyChina )

Translator | Dingdang ( @XiaMiPP )

Editor's Note: Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin published an article yesterday titled "On Idea-Driven Ideas," delving into the role and balance of "idea-driven" and "data-driven" thinking in decision-making. He addressed Conjecture's Gabriel's criticism of his d/acc (defensive/decentralized/differentiated acceleration) framework. Gabriel argued that Vitalik's approach relies too heavily on "ideologies" like decentralization and should instead be more pragmatic and oriented toward the values of humanity as a whole. Using the metaphor of "piece-based" and "situational" chess, Vitalik argued that blockchain and decentralization are not merely technological tools but also enable community cohesion and collaboration. While acknowledging that ideology can interfere with rationality, he emphasized its necessity in complex decision-making and community collaboration, proposing data-driven selection of ideas and the use of limited principles rather than comprehensive ideology to guide action.

Long ago, in the century before the COVID-19 pandemic, I heard economist Anthony Lee Zhang talk about an interesting distinction between "concept-driven thinking" and "data-driven thinking."

The so-called "concept-driven" approach is to first establish a macro-philosophical framework - such as "the market is rational", "concentration of power is dangerous", and "traditions that have stood the test of time are wise" - and then derive more specific conclusions from it through logical reasoning.

On the other hand, "data-driven" approaches start from a null hypothesis, draw conclusions by analyzing data, and accept whatever results the data leads to. The subtext is clear: data-driven ideas seem more worthy of holding on to and promoting.

Last month, Gabriel from Conjecture criticized my approach to the d/acc issue. He argued that rather than starting with an “ideological” approach and then trying to make it compatible with other human goals, it’s better to take a pragmatic approach and use a neutral attitude to find strategies that maximize the satisfaction of the entire set of human values.

Odaily Planet Daily Note: d/acc stands for defensive/decentralized/differential acceleration. It's a philosophy of technological development that advocates prioritizing defensive, decentralized, and differentiated strategies while accelerating technological development to ensure that technological progress maximizes the overall benefit of humanity while avoiding potential risks (such as the concentration of power, technological abuse, or social inequality). It can be understood as a refinement of "accelerationism" (which advocates unrestrained technological progress), emphasizing the selective acceleration of technologies that benefit humanity rather than the blind pursuit of speed.

This view is not uncommon. But it also raises the question: What role should things called "ideology," "principles," "cohesive goals," or "coherent guiding ideas" play in personal thinking? What are their limitations?

My views on this issue can be summarized as follows:

- The world is too complex to deduce every decision from scratch. To be efficient, we must rely on and reuse certain intermediate conclusions.

- Ideology isn’t just a tool for personal cognition; it’s a social construct. Communities need cohesion, and without a shared philosophy or narrative, they often coalesce around a single individual or small group—and this can lead to even worse consequences.

- Encouraging different people to pursue different specific goals helps to form division of labor and collaboration.

- In reality, ideology is often a mixture of means and ends, and we must face this fact.

- Ideology does interfere with rational thinking in many ways, and this is a real and serious problem.

- Good decision-making requires finding a balance between "concept-driven" and "pragmatic mode" and establishing mechanisms to adjust concepts when necessary.

Decision-making in complex situations always has "structure"

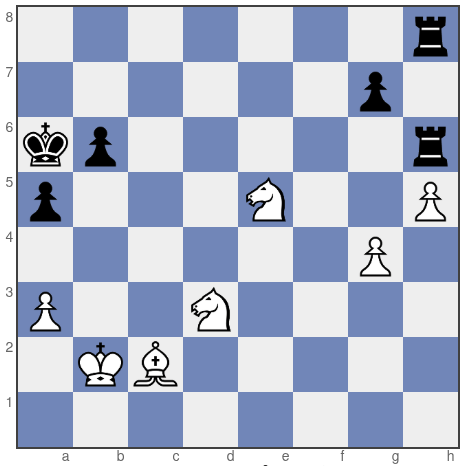

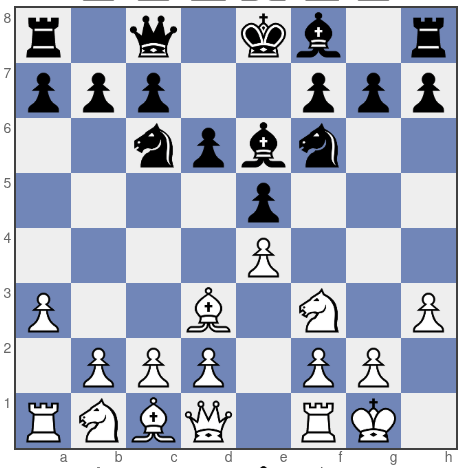

Let's say you want to improve your chess skills. A common rule of thumb in chess is that a queen is worth approximately nine pawns, a rook is worth five pawns, and a bishop or knight is worth three pawns.

Therefore, it is reasonable to exchange "one chariot and one soldier" for "one elephant and one horse", but it is obviously not cost-effective to exchange "one chariot" for "one horse" alone.

This rule leads to a variety of strategic ideas. For example, you can look for opportunities to use your knight to "fork" two high-value pieces—perhaps two rooks, or a rook and a queen. This forces your opponent to choose between having your knight capture one of the strong pieces and then using another piece to capture your knight (a weaker piece) in exchange.

White makes a move. The knight jumps to f 7. The knight jumps to f 7. It is a good move, but you must first know the rule "knight = 3 pawns, rook = 5 pawns" to quickly judge its value.

Here, the rule of "Queen = 9 pawns, Rook = 5 pawns, Knight/Bishop = 3 pawns" is actually a generator of tactical inspiration , which can help you start from a more effective starting point rather than searching blindly.

If we regard this rule as a kind of "ideology", given that chess pieces are called "material" in chess, we can call it "materialism".

Of course, some people partially or completely disagree with "piece-ism." There are times when sacrificing pieces is worthwhile, such as to expose the opponent's king or seize the center of the board. The value of pieces also varies depending on the position. In endgames, I've found that a single knight is often more useful than a single bishop, and two bishops are often stronger than two knights. A chess player who focuses on these positional characteristics in developing strategy might call himself a "positionist."

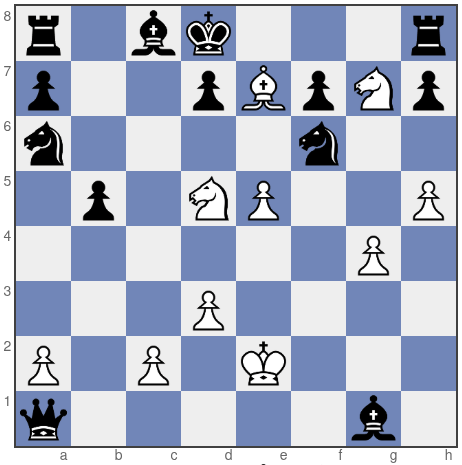

Pawnists and situationists may disagree on certain positions, such as whether to trade two pawns for a bishop:

To eat h3, or not to eat? That is the question.

An ideal chess player might be able to combine the ideas of piece-based and situationalism, switching flexibly according to the situation, which is somewhat similar to the Hegelian synthesis.

But to truly achieve this, a set of clear judgment criteria is needed - when to prioritize sub-force factors and when to focus on situational factors. This set of judgments itself is also a new ideology.

The value of principles in social collaboration

In modern society, effective action often requires collective effort—hundreds, thousands, or even millions of people working simultaneously toward a common goal. While some things can be driven by money (or physical force), this is ultimately limited; much of what we do relies more on intrinsic and social motivation to truly be effective.

In my article on Plurality, I mentioned that there are three main ways communities can collaborate on this:

Collaboration around a mission is incredibly powerful. If you can convince a large number of people that a moonshot is valuable, then once they start moving, they'll invest significant effort, creativity, and energy into achieving it. Ethereum's 2022 merger from Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake is an example of this kind of mission-based collaboration for many community members.

But tasks are one-time, and you don’t want the social capital you’ve accumulated to dissipate after a task is completed. The power of principles and leaders is that they continually generate new tasks: when old tasks are completed, they can continue to lead to new and valuable work.

There's a well-known risk associated with collaboration around leaders : leaders are fragile. History is replete with examples of leaders losing their minds, or, in more benign but equally profound ways, experiencing drift in priorities and values. This applies not only to leadership by a single individual but also to leadership by a group of individuals.

Collaborating around principles —especially those that are not outcome-oriented (non-utilitarian)—can be more robust.

A key characteristic of (well-chosen) principles is what I call their "galaxy brain resistance." The weakness of utilitarianism is that leaders can easily bypass it with clever arguments—they might claim that almost any action they choose will lead to the best outcome because of some complex, "four-dimensional chess"-style second-order reasoning. Principles act as a brake on this tendency: "No matter how clever your reasons, there are some things we won't do because there are clear and well-understood bottom lines."

Seen from this perspective, one of ideology’s main flaws—that it sometimes appears “dumb”—can actually be an advantage.

Another important form of collaboration is internal collaboration , which we often call " motivation ."

I've discovered that some insights into interpersonal collaboration can be applied to the different "sub-agents" within a person—sub-agents that may have different perspectives and goals. Having a clear and consistent principle or goal within not only motivates you at work but also prevents you from straying off track and rationalizing yourself into doing the wrong thing.

Solidify the goal into a professional division of labor

In an organization, if different people belong to different sub-departments and each has a specific mission, it is beneficial to let them have different goals.

A company has a marketing department, a software development department, and many other departments. You don't want people in the marketing department to be too scattered and think about all the ways to make the company successful; you want them to focus on marketing.

This seems to deviate from pure utilitarianism, but strict division of labor and cooperation are the key to enabling the company to complete its tasks in an orderly and stable manner.

I think the grand project of human civilization actually has similar characteristics - we hope that different people can internalize and focus on different sub-goals of civilization.

There’s a subtle but often underestimated reason for this: it makes performance measurable.

If an actor's goal is to "do all useful things," then it is difficult to judge whether he is performing well or poorly, whether he is improving himself or being held accountable externally.

But if the goals are more specific and narrow, you can more clearly evaluate how well they are being accomplished and where improvements can be made.

The benefits can be significant—sometimes significant enough to offset some possible coordination failures between actors with different goals.

Ideology is a mixture of means and ends

So far, I have thought of ideologies primarily as means: they are sets of propositions about how to achieve certain generally agreed-upon goals.

In Gabriel's article , ideology is more about the goals themselves, that is, which goals should be focused on first.

In reality, ideology is always a complex and confusing combination of the two.

So, since ideology also involves goals, how do I fit this into the previous discussion?

Here I will give a slightly "lazy" answer: I think that those goals that we have made specific enough to form an ideology or write down are actually also a means in essence.

Why do we say this? Imagine someone who values freedom very much. Initially, they might say that they value freedom because it leads to a more efficient economy and a more stable society.

But suppose you tell him there's a way to achieve a very efficient and robust economy—one that relies on almost no freedom. For example, you design an advanced computer to manage the economy, telling everyone where to work, and the stability of society depends on a democratic vote held every month to adjust or completely replace the parameters of the computer.

The liberal was very uneasy when he heard this idea. He knew that if this plan was implemented, he would immediately begin planning a rebellion.

Why is this? I believe that “fixed values” are actually a strategy or prediction, while the true ultimate goal (the “victory condition” they pursue) is very complex and difficult to interpret, a bunch of conditions and preferences hidden in each of our minds.

When the liberal hears this proposal for an efficient and robust, yet illiberal, society, he realizes that efficiency and robustness are like “pieces” in chess—an important part of winning the game, but by no means the whole story.

The potential negative impact of ideology

Radical climate change advocates often say they support “degrowth” policies because they are the only way to prevent the planet from overheating.

But if you propose using solar power (or, more extreme, solar geoengineering) to prevent the Earth from overheating without affecting material wealth or capitalism, they can always enthusiastically come up with all sorts of reasons why these options are not feasible or would have too many "unintended consequences."

Cryptocurrency enthusiasts often say they hope to improve global financial access, establish trusted property rights, and use blockchain to solve various social problems.

But if you show a way to solve the same problem without relying on blockchain at all, they will also enthusiastically find various reasons to reject your solution, perhaps because it is "too centralized" or "lacks sufficient incentive mechanisms."

These two examples are somewhat similar to the liberals I mentioned earlier, but they are not exactly the same.

It is reasonable to regard freedom as the ultimate goal (provided that freedom is not your only value). After all, freedom as a goal is deeply embedded in human genes after millions of years of evolution.

But it’s less plausible to view the abolition of capitalism, or the mass adoption of blockchain, as the same ultimate goal.

I think that's essentially the failure mode we have to be wary of: elevating something to be the ultimate goal when it's not, and ultimately severely undermining the underlying goals we're actually trying to achieve.

"But I still have more and stronger pieces in my hand, so even if I am checkmated, mentally I am the real winner."

How do I reconcile these two perspectives?

In the previous sections, I pointed out two positive uses of what you might call “ideology,” “principles,” or “idea-driven thinking”:

- The concept of a "department" drives thinking and action. Just as a company has a dedicated marketing department, society has reason to have a dedicated "department" responsible for protecting the environment. Similarly, chess players should have a dedicated thinking process to answer questions like "Which strategy will help me capture my opponent's pieces while protecting my own?"

- Principles as a coordination tool. Rather than rallying around a leader or elite, rallying around an idea is more resilient and less susceptible to failure or manipulation.

Social movements often encompass both. Externally, they strive to defend a principle and reduce society's over-reliance on elites; internally, they focus deeply on a specific theme, fostering valuable ideas and strategies for improving the world. For example, libertarian economists defend social freedom while also developing beneficial ideas like prediction markets and congestion pricing. Environmentalists use political advocacy to prevent irreversible environmental damage while also promoting technological innovations like clean energy and synthetic meat.

Two failure modes I see

First, some instrumental goals are overly solidified and pursued to an extreme, which in turn subverts the original fundamental goals.

Second, coordination around an open-ended goal can easily slide into a situation where an elite class is responsible for interpreting the goal.

This is what Balaji Srinivasan calls "democracy is essentially the rule of Democrats," and why the effective altruism movement has been criticized for shifting from broadly promoting effective philanthropy to narrowly addressing AI safety and only funding people within its own circle.

I propose two compromises that attempt to balance these pros and cons:

- Use data to drive your choice of ideas. Maintain a set of knowledge topics that can generate hypotheses, then use data analysis to determine which to prioritize and which to ignore. Bryan Caplan does this well. While he has a strong liberal ideology, he also values empirical rigor, so his core advocates (such as more open immigration, reduced education, and deregulation of housing) are well-supported by the evidence. While his liberalism also leads him to believe in many things I disagree with, he rarely promotes ideas that lack substantial data support. You can still disagree with his extreme views, but I find him more rational among the extremes, so I think his approach does have merit.

- Principles, not ideologies. The subtle difference between the two is that principles are often restrictive, while ideologies are often comprehensive. Principles give you a set of dos and don'ts, and then stop there; ideologies have no boundaries; you can pursue them indefinitely. This distinction is only a rough one, but I think it's profoundly significant. Focusing social coordination on principles that "keep us from going off the rails" allows a movement (or individual) to benefit from more pragmatic thinking under normal circumstances while maintaining considerable robustness.

The complexity and internal structure of the world and our minds (individually and collectively) mean that simply "rationally weighing all values and making the best data-driven choice" often fails in practice in various ways. At the same time, over-reliance on any one structure can also break down, sometimes even worse. Only by finding a balance between the two can we best achieve greater benefits while minimizing the drawbacks on both sides.