Leading the introduction of Hong Kong in the United States: Detailed explanation of Singapores encrypted stable currency regulatory framework

Original author: William, Wu Shuo blockchain authorized release

With the development of financial technology and changes in global geopolitical relations, governments around the world are gradually realizing the huge potential of stablecoins. Countries and regions such as the European Union, the United States, Singapore and Hong Kong have successively launched consultation and legislative activities in order to seize opportunities in the future. On August 15, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) announced the final regulatory framework for stablecoins, becoming one of the first jurisdictions in the world to incorporate stablecoins into the local regulatory system. In the near future, Hong Kong, China, and the United States will both introduce stablecoin regulations. Therefore, the regulatory framework released by Singapore this time is of great value and will become a reference template for regulatory agencies in various countries to a certain extent. To this end, this article will analyze in detail the Singapore stablecoin regulatory framework and gain insight into the future development trends of global stablecoin regulation.

1. Key Points of Singapore’s Stablecoin Regulatory Framework

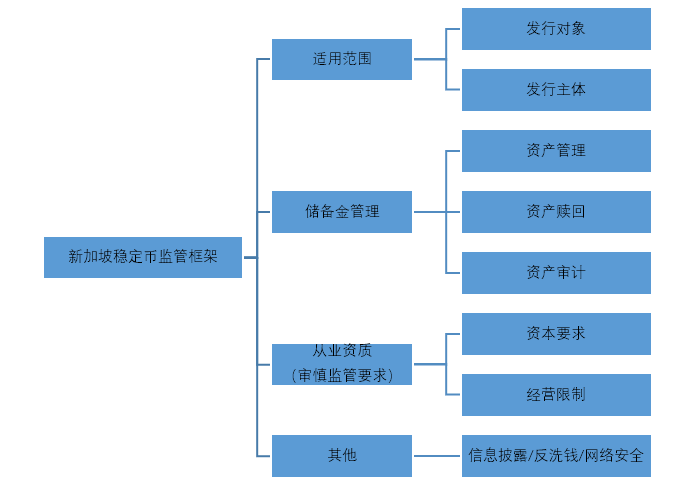

MASs earliest regulatory attempt on stablecoins can be traced back to the PS Act introduced in December 2019, and then issued a consultation document in December 2022 to solicit public opinions on the proposed stablecoin regulatory framework, and finally in this years The final stablecoin regulatory framework was finalized on August 15. Therefore, Singapore’s complete regulatory framework for stablecoins involves the contents of the above three regulatory documents, not just one of them. According to the author’s review, Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework mainly includes the following parts:

Figure 1 Highlights of Singapore’s Stablecoin Regulatory Framework

1. Scope of application

The regulatory framework for stablecoins introduced by Singapore this time has aroused market concern about the openness of the objects of stablecoin issuance. MAS allows the issuance of a stable currency [1] (Single-currency stablecoin, referred to as SCS) anchored to a single currency, and the anchor currency is the Singapore dollar (SGD) + G 10 currency [2]. Generally speaking, a countrys currency is a symbol of its sovereignty and other countries have no right to manage it. But MAS allows stablecoins to be anchored to other countries’ currencies, which is a major breakthrough. It shows that MAS has a certain degree of openness and innovation, fully taking into account the national conditions of G 10 countries and communicating with them.

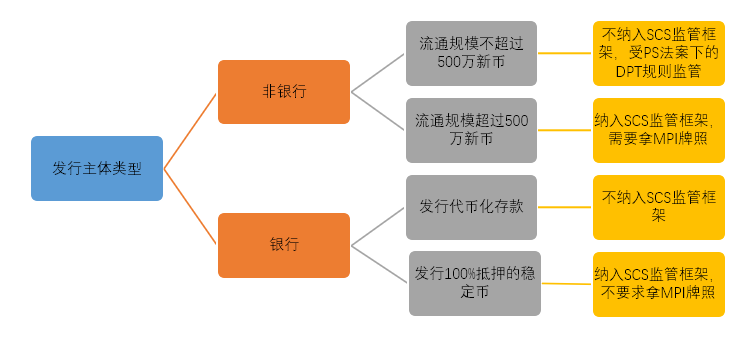

Secondly, MAS has made major adjustments in terms of issuing entities. MAS divides stablecoin issuers into two major categories: banks and non-banks. For non-bank issuers, MAS requires that only stablecoins with a circulation scale of more than 5 million Singapore dollars be included in the stablecoin regulatory framework, and they need to apply for an MPI license under the PS Act; otherwise, they do not fall under the scope of stablecoin supervision and only need to meet the PS Act. DPT regulations under. For banks, MAS originally planned to include tokenized deposits into the category of stablecoins, but there is a huge gap in the nature of the assets between the two (deposits are the product of the bank reserve system, are not 100% mortgaged, and are bank liabilities), and eventually they will be included. Eliminated, therefore banks must also issue 100% asset-backed stablecoins, but it should be noted that banks do not need to apply for an MPI license. The explanation given by MAS is that the Banking Act already requires banks to meet relevant standards.

Figure 2 Regulations on the scope of issuers

2. Reserve Management

Regarding reserve fund management, MAS has made detailed regulations, mainly in the following areas:

First of all, in terms of asset composition, MAS requires that reserves are only allowed to be invested in cash, cash equivalents, and bonds with a remaining maturity of no more than three months, and has detailed regulations on the qualifications of asset issuers: either issued by the government/central bank Currency Cash, either an international institution rated AA- or above. It is worth noting that MAS has a restrictive interpretation of cash equivalents: it mainly refers to bank institution deposits, checks and drafts that can be quickly paid into cash, but does not include money market funds. Therefore, investing 90% of assets in money market funds like USDC, or even investing in some commercial papers like USDT, does not meet MAS regulatory requirements.

Secondly, in terms of fund custody, MAS requires the issuer to set up a trust and open a segregated account to separate its own assets from reserves; it also makes clear regulations on the qualifications of the fund custodian: it must have custody services in Singapore A licensed financial institution, or an overseas institution with branches in Singapore and a credit score of no less than A-. Therefore, stablecoin issuers who want to be included in the MAS regulatory framework in the future must find a financial institution that is local or has a branch in Singapore.

Finally, in terms of daily management, MAS requires that the daily market value of the reserve fund be higher than 100% of the SCS circulation scale, and that the redemption shall be redeemed at face value, and the redemption period shall not exceed 5 days, and the monthly report shall be published on the official website Audit Report.

3. Qualifications

What is striking about this regulatory framework is that MAS has detailed regulations on the qualifications of stablecoin issuers as part of prudential supervision. MAS mainly stipulates the qualifications of issuers in three aspects:

The first is the Base Capital Requirement, which is similar to the Basel Accord’s requirements for the banking industry’s own capital. MAS stipulates that the capital of a stablecoin issuer shall not be less than S$1 million or 50% of annual operating expenses (OPEX).

The second is the solvency requirement (Solvency), which requires liquid assets to be higher than 50% of annual operating expenses or to meet the needs of normal asset withdrawals, and this scale needs to be independently verified. It should be noted that MAS clearly stipulates the categories of liquid assets, which mainly include cash, cash equivalents, claims on the government, certificates of deposit, and money market funds.

Finally, there is the business restriction requirement (Business Restriction), which requires the issuer not to engage in lending, staking, trading, asset management and other businesses, and the issuer is not allowed to hold shares of any other entity. However, MAS also made it clear that stablecoin issuers can engage in the business of hosting stablecoins and transferring stablecoins to buyers. This actually restricts stablecoin issuers from conducting mixed operations. Furthermore, MAS clearly stated that stablecoin issuers are not allowed to pay interest to users through activities such as lending, staking, and asset management. But other companies could provide similar services for stablecoins, including sister companies in which the stablecoin issuer does not have a stake.

4. Other regulatory requirements

MAS also has regulations on information disclosure, qualifications and restrictions of stablecoin intermediaries, network security, and anti-money laundering, but there is nothing worthy of attention. Therefore, this article does not expand the analysis. Interested readers can read relevant documents by themselves .

2. On the pros and cons of Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework

The promulgation of Singapore’s stablecoin regulatory framework has a huge impact on both the compliance development of the global stablecoin industry and the demonstration and leadership of other countries, so I won’t go into details here. Here we mainly focus on several areas where MAS can continue to be improved in the future.

This MAS stablecoin regulatory framework has shelved or obscured the following important issues, which may cause hidden dangers in the near future.

The first is the issue of the type of reserves. The denominated currency of MASs original planned reserves must be consistent with the anchor currency, that is, the issuance of a Singapore dollar stable currency, and its reserve assets must be Singapore dollar assets rather than US dollar assets. But this will bring about a serious problem: users are very concerned about whether stablecoin deposits and withdrawals are in mainstream currencies such as the US dollar. If the Singapore dollar stable currency can only be exchanged for the Singapore dollar, the stable currency will not have a competitive advantage, and the issuance volume will be very small; secondly, the types and depth of investable assets in some anchor currencies are very limited, and reserve management will be difficult. A major challenge. MAS should also be aware of these issues, but it does not explicitly allow reserves to be invested in different currency assets, but only reiterates that issuers need to control risks and meet the 100% reserve requirement.

Secondly, there is the issue of cross-jurisdictions. MAS has proposed two solutions to solve this problem. One is that issuers submit a certification document every year to prove that stablecoin issuance in other regions also meets the same standards; the other is that with different jurisdictions To establish cooperation. However, in the end, both of the above solutions could not be realized due to practical factors. For this reason, MAS could only settle for the next best thing and require stablecoin issuers to not allow cross-jurisdictional issuance at the initial stage. However, some stablecoins have now become global stablecoins, issued in different regions and on different public chains. If the issuer fulfills the above requirements, it may lose its market competitiveness.

The final regulatory issue for systemically important stablecoins. In last years consultation paper, MAS described what systemically important stablecoins are, and hopes to regulate them according to the standards of financial market infrastructure. However, based on practical factors, MAS has currently chosen to put aside the dispute to see the consequences.

Putting aside the regulatory content itself, an important question that the market is also concerned about is: What are the gains and losses of issuing compliant stablecoins in Singapore?

On the one hand, the advantage of compliant stablecoins lies in their compliance. For example, due to its own compliance and security, compliant stablecoins give users greater confidence. Furthermore, MAS requires that compliant stablecoins be labeled MAS-Regulated Stablecoin to distinguish them from other stablecoins. It is conducive to the promotion of stable coins; for example, because compliance is more recognized by traditional financial institutions, there are fewer obstacles from banks when depositing and withdrawing funds.

On the other hand, we should also pay attention to the cost of compliant stablecoins. First of all, MAS clearly stipulates the qualifications for issuance, and makes clear regulations on its own capital, solvency and business scope, while the existing stablecoin issuers are not restricted by such regulations; secondly, the issue of market fairness, MAS stipulates that banks issue Stablecoins do not need an MPI license, but non-bank issuers need to apply for an MPI license. At present, the cycle of applying for MPI is about 1-2 years, and there are many review requirements for enterprise qualifications. Since the implementation of the PS Act in 2019, the number of enterprises that have obtained MPI licenses is not large. Therefore, if you want to issue compliant stablecoins in Singapore, you need to pay a lot of time, manpower and material costs.

To sum up, under the current MAS stablecoin regulatory framework, banks or large and powerful companies are more likely to issue MAS-Regulated Stablecoin; for non-bank small and medium-sized enterprises, the current policy is not friendly.

[ 1 ] Note: MAS does not allow the issuance of stablecoins linked to a basket of currencies, nor does it allow the issuance of stablecoins linked to digital assets and algorithms.

[ 2 ] Note: G 10 currencies include Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, British pound, Euro, Japanese yen, New Zealand dollar, Norwegian krone, Swedish krona, Swiss franc and U.S. dollar