Analyzing the status quo of the aggregator track: What are the advantages of Li.Fi?

Original title: Revisiting Aggregation Theory

Original compilation: Kxp, BlockBeats

Original compilation: Kxp, BlockBeats

A year ago, we wrote about Aggregation Theory in the Web3 Era. In the Web 2.0 era, aggregators benefit from reduced distribution costs and bring together a multitude of service providers. Platforms like Amazon, Uber, and TikTok profit handsomely from the service or value provided to users by hundreds of suppliers, creators, or drivers. At the same time, users also get endless choices. For creators, scale is key. I chose to tweet on Twitter instead of Lens because my followers are mostly on Twitter.

In Web 3.0, aggregators rely primarily on the reduction of verification and trust costs. If you use the correct contract address, then you don't have to worry about exchanging to fake USDC on Uniswap. Marketplace platforms like Blur don't need to expend resources to verify the authenticity of every NFT traded on the platform, because the network itself bears this part of the cost.

Aggregators in Web3 can more easily check asset prices or find their listing location by examining on-chain data. Over the past year, most aggregators have focused on aggregating on-chain datasets and making them easily accessible to users. This data may relate to prices, yields, NFTs, or asset bridging pathways.

The assumption at the time was that those companies that rapidly expanded as the aggregator interface would establish a monopoly. I specifically mentioned Nansen, Gem, and Zerion as examples. Ironically, however, looking back over the past year, my assumption wasn't accurate -- and that's what I want to explore today.

Weaponized Token

Don't get me wrong. Gem was acquired by OpenSea a few months later. Nansen raised $75 million and Zerion raised $12 million in October. So, from an investor's perspective, my assumption is correct. Each of these products is a leader in its field, but what prompted me to write this article is that the relative monopoly I predicted did not materialize. Instead, they have all faced the emergence of competitors over the past year. This is a desirable trait in an emerging field.

So, what has happened in the past few years? As I wrote in "Royalty Wars", the relative monopoly of Gem (and OpenSea) was threatened when Blur entered the market. Likewise, Arkham Intelligence combines an exciting user interface, possible token issuance, and a clever marketing strategy of rewarding tokens through referrals to compete with Nansen. Zerion may feel relatively at ease, but Uniswap's new wallet launch could erode their market share.

Do you see a trend here? Aggregators that had no tokens in the past and relied on equity investors to support steady growth are now facing the risks posed by companies that issue tokens. This concept of “community ownership” will become increasingly important as we move deeper into a bear market, as finite consumers who hold their ground look to get the most out of every dollar they have. Additionally, there is a novelty in using the platform to earn rewards instead of paying to use it.

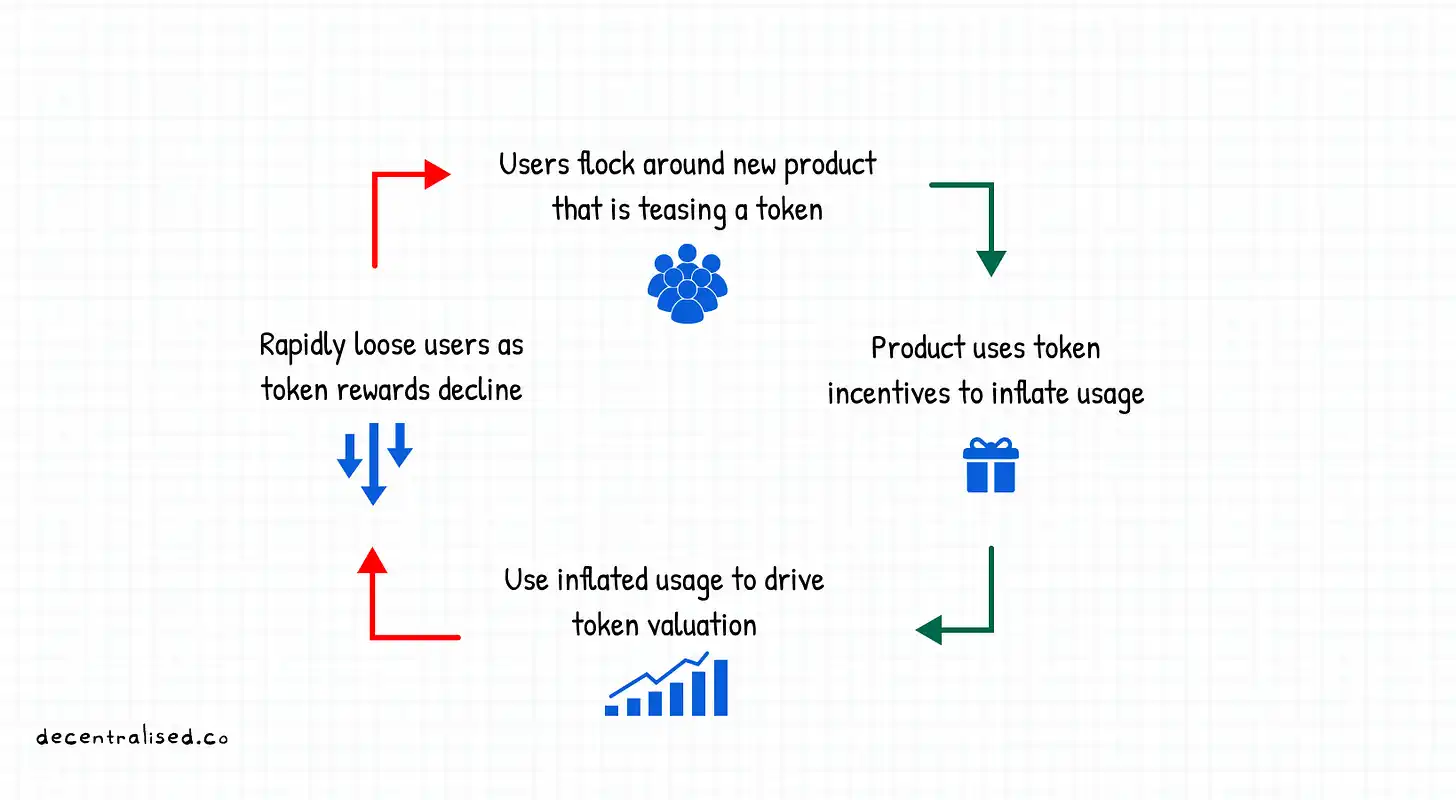

So, on the one hand, companies that have been cash-flow positive for a long time will see revenue decline; on the other hand, they will see users flock to competitors. Is this sustainable? Absolutely not possible, here's how it works:

The company launches a product that implies a token, and it would be even better if the launch was tied to a referral program. For example, Arkham Intelligence provides Tokens to users who visit their platform, and considering the possibility of airdrops, more and more users will spend time on this product. This is a feature, not a bug.

It’s an incredible way to stress test a product, reduce customer acquisition costs, and channel network effects into a product. The challenge lies in the retention rate of users. Once the Token reward is no longer available, users usually switch to other products. Therefore, most developers who "hint" Token do not know how big their user base is.

Here’s a guy who sums up the philosophical underpinnings of the average person in crypto today, and pretty well sums up the self-interested behavior that drives our world:

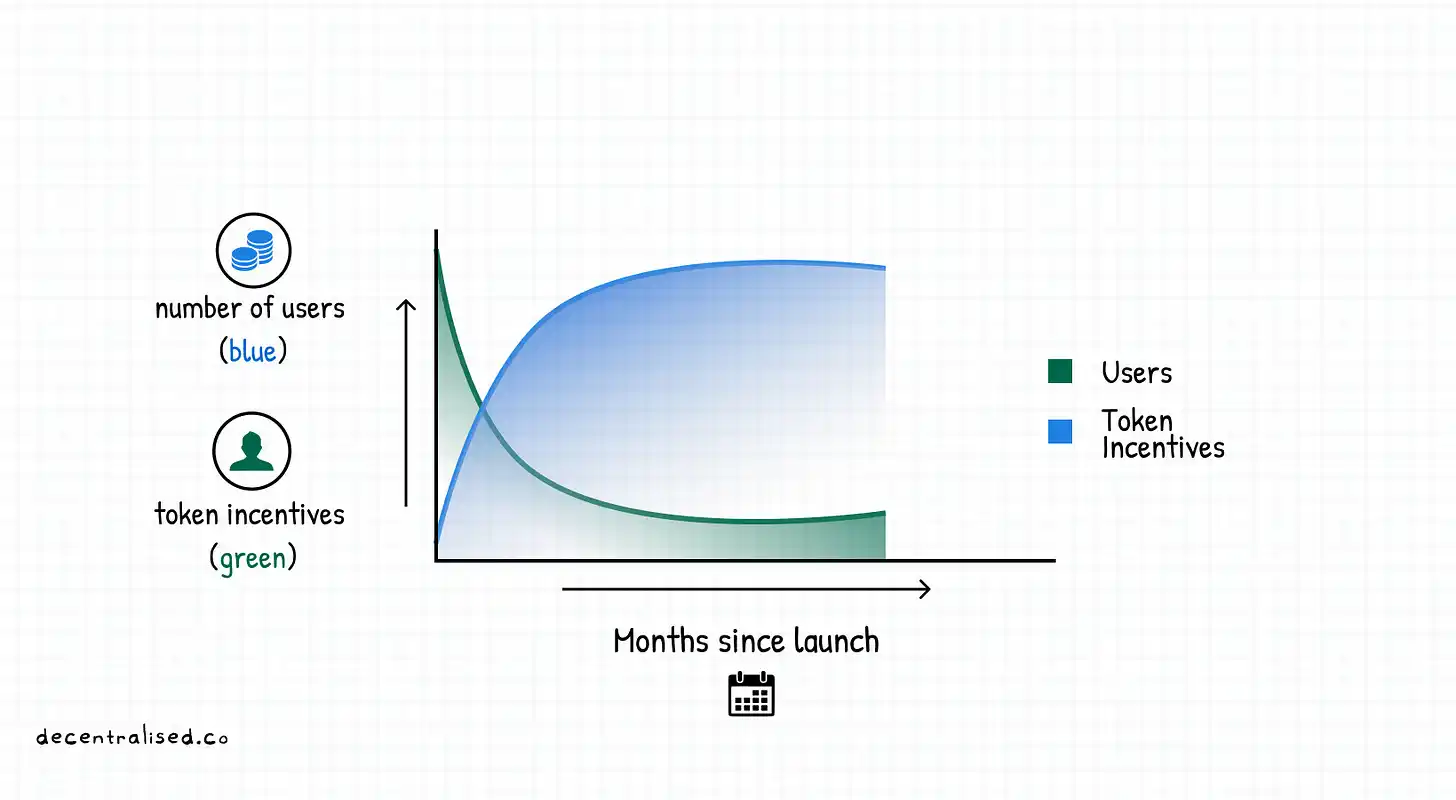

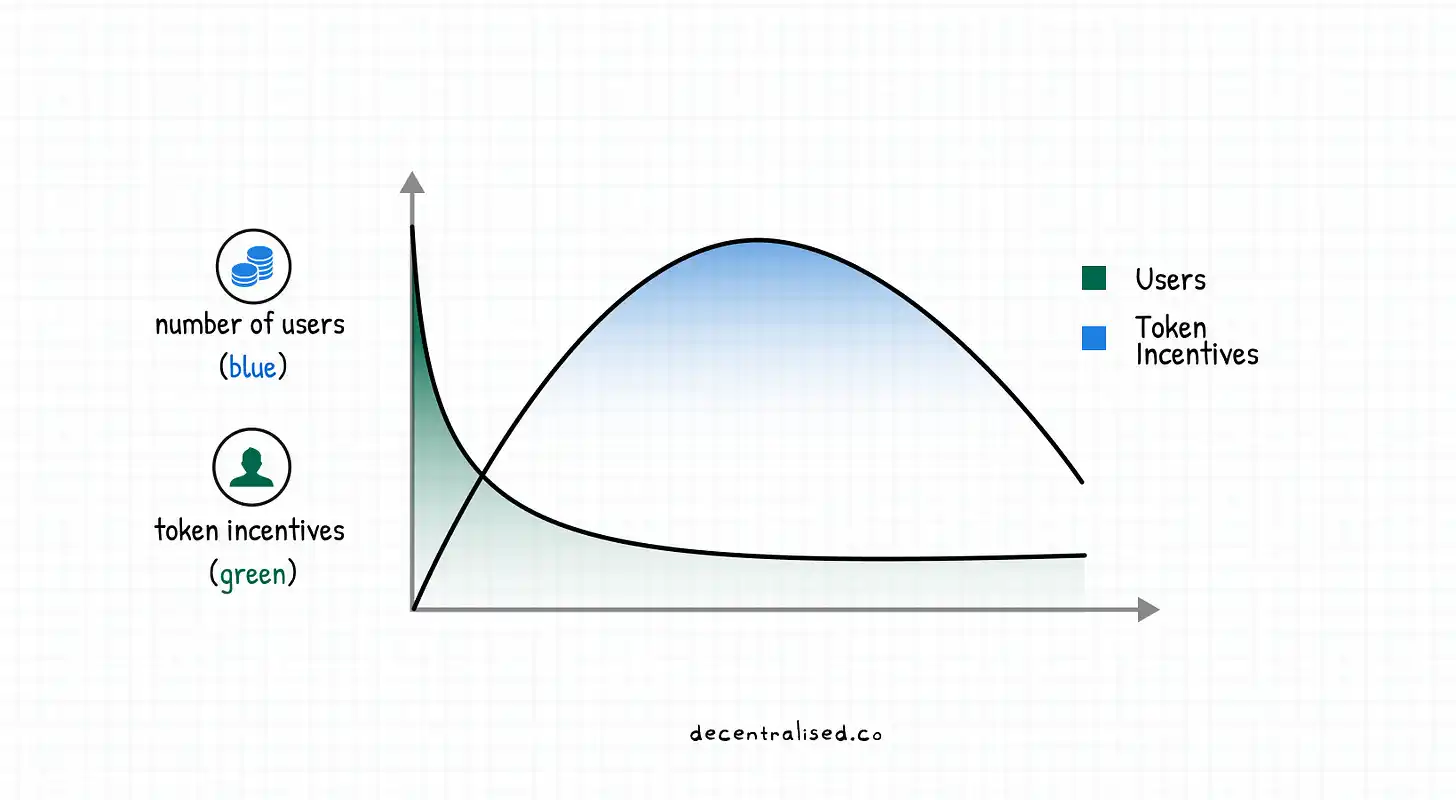

It is worth noting that there was a historical trend in the past, that is, users abandoned Token issuance projects and turned to existing projects. The trap here is that the founder (probably) thinks that the users acquired through Token incentives are sticky. Under ideal conditions, the relationship between Token incentives and product users should be as shown in the following figure:

But the reality is that the initial influx of users has almost completely abandoned the project as token incentives have diminished. They have no reason to keep contributing to the product after losing the incentive that attracted them in the first place. This phenomenon has plagued DeFi and P2E for the past two years.

Users who accumulate tokens and hold them become new "community" members who want to know when the asset price will rise significantly so that they can exit.

(I have argued that market participants are self-interested actors acting rationally.)

My original thesis of simply centralizing the feature sets of multiple products onto a single interface, using the blockchain as the backbone of the infrastructure, as a durable moat, is most likely wrong. I wonder why leaders with relative advantages are replaced by other companies in Web3. Binance toppled Coinbase and they faced competition from FTX. OpenSea sees competition from Blur. Sky Mavis, maker of Axie Infinity, could face the heat as new entrants such as Illuvium enter the market. Why are Web3 users leaving over time? How to retain a user long enough?

In the Web3 era, when everyone can publish a version with an embedded Token, what can become a kind of moat? I've been thinking about this question a lot because we live in a narrative shifting market where every quarter there's a new "hot" thing. That's why the venture capitalists I'm following went from experts on remote work to experts on Taiwan's geopolitical tensions overnight.

image description

This also applies to how consultants can change their LinkedIn resumes

You ultimately want an investment of time, money, or energy to grow without the need for active management. And the only way this can be done is for products that do two things: first, retain the users they already have, and second, scale aggressively to prevent competition from eroding their market share. So, what can be done to achieve this? (You know it’s a bear market when people start thinking about moats and user retention)

competition is only for losers

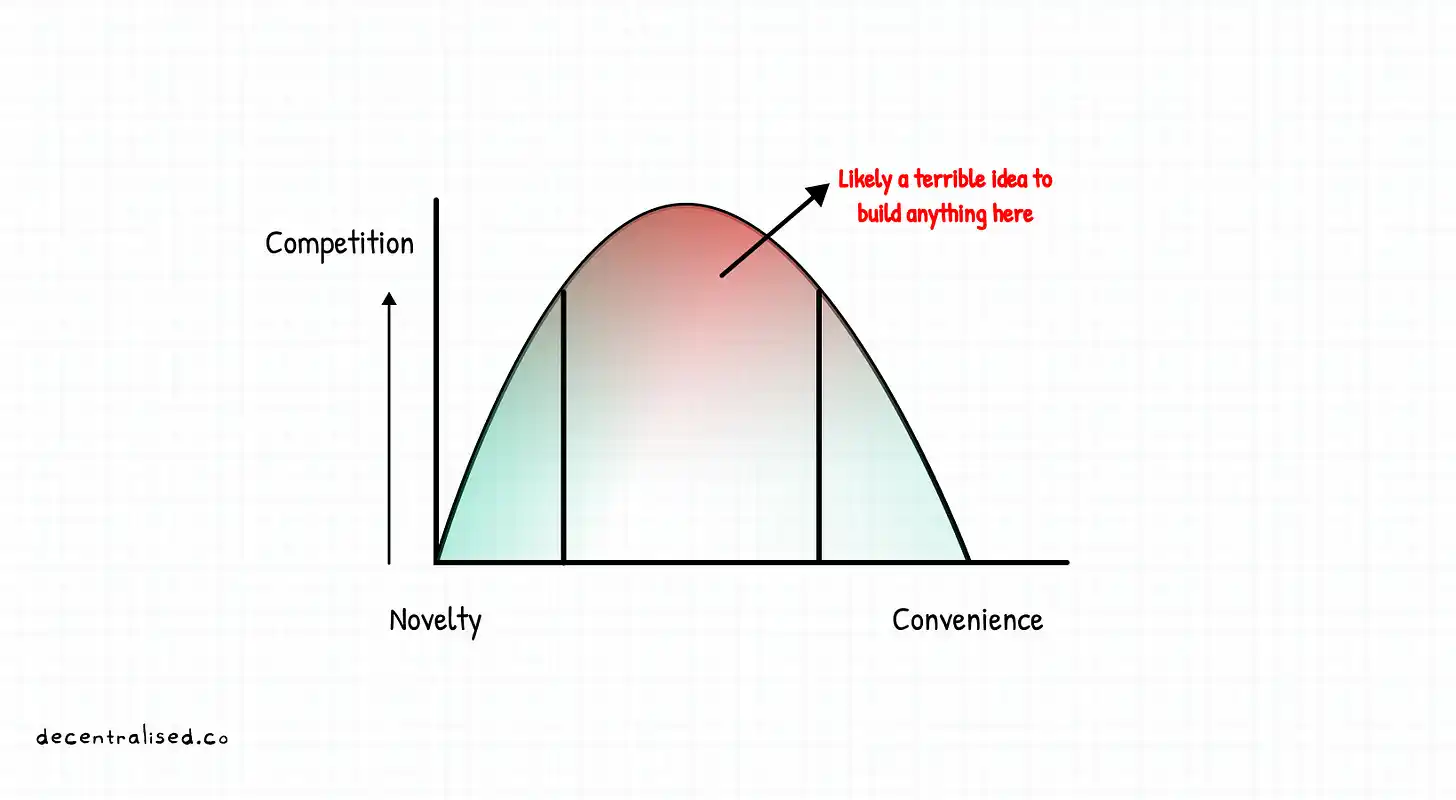

Part of the reason for this phenomenon is to place the company rankings on a spectrum between innovation and convenience. In the early days, the novelty of an original product like an NFT attracted those willing to go to any lengths to try the product.

It is easy for us to deal with the seed phrase in the wallet, because the novelty of using "digital currency" is enough to attract us. If you notice how curious users are about Ordinal, you realize how patient they are. The early profit factor is what drives users to persevere through tough times to speculate and profit.

At the other end of the spectrum are the high-convenience tools we rely on every day. Amazon is an example of an aggregator that has us addicted to convenience. Consumers may benefit from buying from a niche store that is not on Amazon, and may not be reasonably priced on Amazon.

But the last thing you need to worry about when making your decision is payment options, delivery times, or customer support. This psychological "saving" translates into spending more attention or capital on the aggregator. Many sellers come to Amazon precisely because they understand that consumer behavior in the marketplace is different than if the user came directly to the store.

A 2018 article by Tim Wu summed up the efforts people made for convenience:

Of course, we are willing to pay a premium for convenience, and often more so than we realize. For example, in the late 1990s, music distribution technologies like Napster made it cheap to get music online and attracted a lot of people to use it. But while it's still easy to get music for free today, no one really does because the iTunes store, introduced in 2003, made buying music much more convenient than illegal downloads.

Going back to the spectrum I mentioned initially, novel technologies often pay users to try them. Conversely, high-convenience apps make users pay top dollar for the convenience.

The challenge with most consumer facing applications today is that they are in the middle of the "valley of death", what I call the middle ground. They are neither novel enough to be tempted to try nor convenient enough to be relied upon without outside intervention. Skiff, Coinbase Card, and Mirror are great at substituting their traditional counterparts on the convenience spectrum of this equation.

However, take gaming, lending, or identity tracks as examples, and you'll see why these topics haven't scaled on-chain yet.

Most apps in the middle make the fatal mistake of competing with each other. First by advertising and recruiting, increasing customer acquisition costs and employment costs, and then by creating memes and posting narratives against peers to compete. As Peter Thiel said: Competition is for the losers.

When startups start competing in niche markets, there are usually no winners. In his words, the only way startups can turn from the struggle to survive is to have monopoly profits. But how can this be achieved?

emerging moat

In Web3, if a company wants to realize a development path other than Token, it can focus on three aspects: cost, application cases and distribution. There have been a few instances in the past, so I'll cover those one by one.

cost

Stablecoins have become the killer use case for cryptocurrencies because they provide a better experience than traditional banking on a global scale. In India, innovations such as UPI may be more cost-effective, but to move funds between Southeast Asia, Europe or Africa, or simply move balances between bank accounts in the US, it makes more sense to use on-chain transfers.

From the user's perspective, the costs incurred are not just the money spent on the amount transferred, but also the time and effort required to move the funds. Debit cards are to e-commerce what stablecoins are to remittances: reducing the cognitive cost required to transfer money. You can offer slightly higher yields than most consumer-facing yield-generating mobile apps, but the value proposition will fail given the risk of crashes.

distribution

If you gather niche users in emerging industries, distribution can become a moat. Just think about how Compound and Aave unlock a new lending market. Very few people would find it worthwhile to take out a $50 loan against $100 of Ethereum collateral. But many people ignore that there is a market that is not being served-mainly those crypto rich who do not want to sell their assets in a bear market.

You would be wrong to think that people in emerging markets without access to credit lines would drive the volume of DeFi lending. But in reality, the driving force is the crypto-rich, a population that was previously unbanked. Becoming a “hub” related to a field can attract users’ attention, which in turn can promote the development of a single function. Coingecko and Zerion are two companies that have done well in this regard.

Given that the marginal cost to a company of driving users to a new feature is next to zero, it becomes cost-effective to iterate and add new revenue streams to the product itself. This is why platforms like WeChat (in Southeast Asia), Careem (in the Middle East) and PayTM (in India) tend to do well.

When players like Uniswap release wallets, they are actually trying to bring users together in an interface where they can push more features (like their NFT marketplace) at a lower cost.

Example

Products such as ENS, Tornado Cash, and Skiff have built loyal user bases who value unique features that these traditional alternatives cannot offer. For example, Facebook does not associate wallet addresses with user identities, while Tornado Cash offers unrivaled privacy that is more user-friendly than banks.

You can imagine that users of these products often stick with them because there are often no comparable alternatives. However, introducing new use cases requires educating users and raising user awareness, which takes time. However, being the first to market can capture the majority of the market share.

In its early days, LocalBitcoins was the only peer-to-peer trading platform and helped aggregate liquidity in emerging markets such as India, keeping it at the top until 2016.

Scaling a product by focusing on traditional means of growth is difficult in a bear market. The aforementioned products have survived multiple market cycles. The success of Axie Infinity is due to the team's two years of groundwork leading up to 2020, enabling them to build a strong community, manage the token, and balance the interests of investors and users.

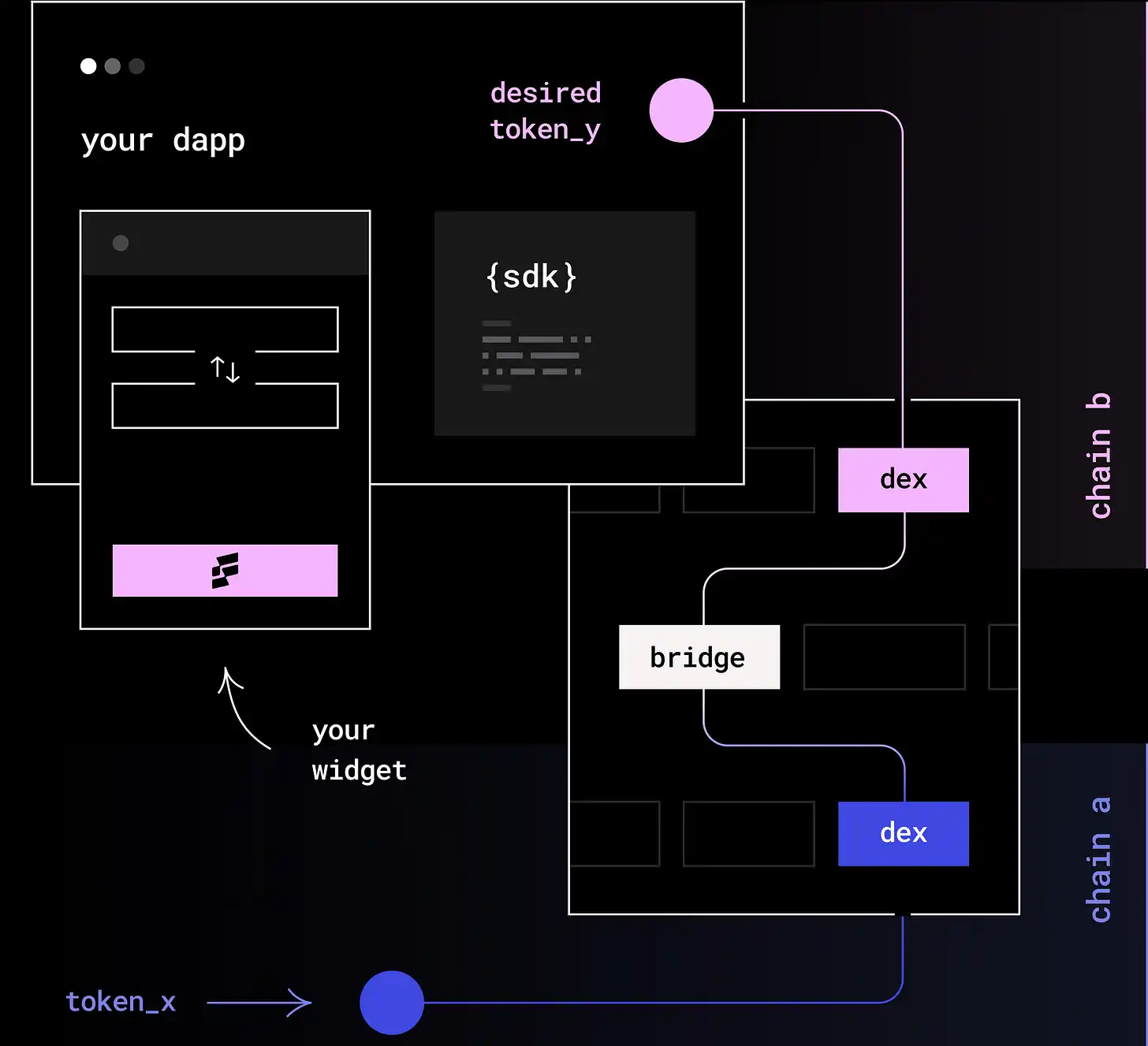

This is why VCs like to invest in developer tools and infrastructure during market downturns. In response to the lack of interest from retail users, companies turned their attention to enterprise-oriented solutions and built tools for developers so they could attract retail users. Coinbase has realized this, releasing tools such as wallet API in the bear market. LI.FI is the poster child for this trend, providing developers with an SDK to enable their applications and users to support multiple chains.

From Novelty to Convenience

image description

Think of aggregators (like Li.Fi) as building blocks that developers place in their applications to help users move assets between chains at minimal cost

Although there are many similar competitors in the market, LI.FI is a good example because they meet the criteria I mentioned before, and Philipp shared them with me eight months ago, and I have always used them as the basis of this article. But let's go back to LI.FI's strategy.

LI.FI has done several things to meet the criteria I mentioned earlier and built a strong moat:

· They focus on enterprises rather than retail investors and aim to attract developers building applications that require cross-chain transfers.

· Their products can save research and maintenance time and resources for enterprises, and are relatively easy to sell in a bear market.

· For end users, LI.FI provides the best transfer cost basis, increasing the willingness to use its SDK-integrated products.

· They are the first platform to integrate a new chain with less competition.

· Their target user group is mainly industry leaders who are already familiar with cryptocurrencies, and they don’t need much knowledge popularization work.

Although LI.FI is not the only cross-chain aggregator in the market, and even if they meet the cost, demographic and use case criteria I mentioned earlier, it will be difficult for any one aggregator to build a strong moat. I'm interested in how LI.FI gradually transforms from a novelty tool to a convenience tool.

In the early days, users relied on bridge aggregators because transferring assets between different blockchains was a time-consuming process that required going through centralized platforms and security checks. Today, DeFi users are sending billions of dollars across chains, but ordinary people are not interested.

So how do you survive when the novelty wears off? If you pay attention to how Nansen and LI.FI work, you can get the answer by looking at who they sell their products and services to: LI.FI sells mainly to developers, and yesterday Nansen launched Query, which is a A tool for corporates and large funds to directly access Nansen data, which they claim is sixty times faster than its closest counterpart at querying the data. So why are both companies focused on developers?

The key question for anyone using the Nansen query tool is whether the tool saves enough time and effort to justify the cost. Decision makers often avoid building from scratch if the cost of developing the tool in-house is lower than the cost of commissioning a third party (eg LI.FI).

To stand out as a convenience tool, businesses must focus on a small number of high-yield users who are willing to pay for the added value of the product. By catering to these users, a business can generate enough revenue to attract more users to its product and become the convenient tool of choice.

I talked to Alex from Nansen about this framework, and he made a different point of view. Users are always looking for value, regardless of market conditions. In a bear market, large customers such as enterprises and networks require specific data sets that are often not available from third-party vendors. By customizing a product to meet their needs and demonstrate its value, companies can generate more revenue and face less competition.

back to basics

In my previous article, I mistakenly believed that using blockchain is a competitive advantage and not just a product feature. Since then, many DeFi yield aggregators have launched, but most of them have failed. Simply integrating blockchain may not matter if competitors can use the same functionality and provide a better user experience or introduce tokens like gems. In this competitive environment, we need to think about what really differentiates products.

As I write this, a few trends are evident. First, acquiring users in a bear market is expensive because interest from retail investors is low. Unless the product is novelty or convenience, the product is in a tough position. Second, businesses that focus on building products for other businesses (B2B) can achieve sustainable growth and capture the market in a bull market, just like FalconX. Third, a poorly designed token can only become a competitive advantage for a while, but it will be a burden in the long run. Only a few communities have successfully increased the value of the token.

Original link