Vitalik Buterin: The Incomplete Guide to Stealth Addresses

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Compilation of the original text: The Way of DeFi

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Compilation of the original text: The Way of DeFi

One of the biggest remaining challenges in the Ethereum ecosystem is privacy. Anything that goes onto a public blockchain is public by default. Increasingly, this means not just money and financial transactions, but ENS names, POAPs, NFTs, soulbound tokens, and more. In practice, using the entire suite of Ethereum applications involves exposing important parts of your life for anyone to view and analyze.

How to improve this situation has become an important issue, which is widely recognized. However, so far, discussions on improving privacy have largely revolved around one specific use case: privacy-preserving transfers (often self-transfers) of ETH and mainstream ERC 20 tokens. This post will describe the mechanics and use cases of a different class of tools that can improve Ethereum's privacy status in many other contexts: stealth addresses.

first level title

What is Stealth Address System?

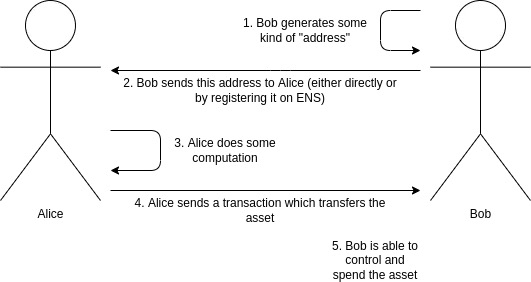

Suppose Alice wants to give Bob an asset. This could be a certain amount of cryptocurrency (e.g. 1 ETH, 500 RAI), or it could be an NFT. When Bob receives the asset, he doesn't want the world to know that he got it. It's impossible to hide the fact that a transfer happened, especially if it's an NFT with only one copy on-chain, but it might be more feasible to hide who the recipient is. Alice and Bob are also lazy: they want a system where the payment process is exactly the same as it is today. Bob sends Alice (or registers with ENS) some kind of "address" encoding how someone can pay him, and this information alone is enough for Alice (or anyone else) to send him the asset.

Note that this is different from the privacy offered by tools like Tornado Cash. Tornado Cash can hide transfers of mainstream fungible assets like ETH or major ERC 20 tokens (although it is easiest to use to send privately to yourself), but it is very weak at adding privacy to unknown ERC 20 transfers, and it There is no way to add privacy to NFT transfers.

Common workflow for payments with cryptocurrencies. We want to increase privacy (no one can know it was Bob who received the asset), but keep the workflow the same.

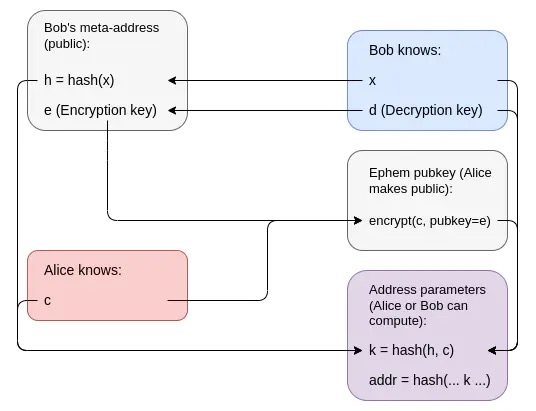

Stealth addresses provide such a solution. Stealth addresses are addresses that can be generated by either Alice or Bob, but only controlled by Bob. Bob generates and keeps a spending key secret, and uses that key to generate a stealth meta address. He passes this meta-address to Alice (or registers on ENS). Alice can perform calculations on this meta-address to generate a stealth address that belongs to Bob. She can then send any assets she wants to this address, and Bob will have full control over those assets. Along with the transfer, she publishes some additional encrypted data (a temporary public key) on-chain that helps Bob discover that this address belongs to him.

Another way: Stealth addresses provide the same privacy properties as Bob, generating a new address for each transaction, but without requiring any interaction from Bob.

The complete workflow of the stealth address scheme is as follows:

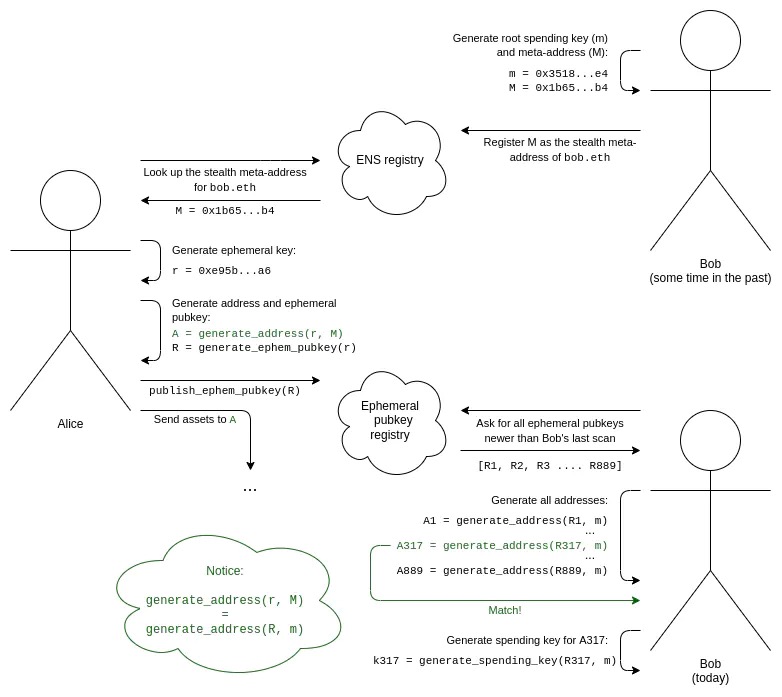

1. Bob generates his root spending key (m) and stealth meta address (M).

2. Bob adds an ENS record to register M as the stealth meta address for bob.eth.

3. Let's assume Alice knows that Bob is bob.eth. Alice looks up his stealth meta-address M on ENS.

4. Alice generates an ephemeral key that only she knows, and she uses only once (generating this particular stealth address).

5. Alice uses an algorithm that combines her ephemeral key with Bob's meta address to generate a stealth address. She can now send assets to this address.

6. Alice also generates her ephemeral public key and publishes it to the ephemeral public key registry (this can be done in the same transaction as the first transaction that sent the asset to the stealth address).

7. In order for Bob to discover the stealth address that belongs to him, Bob needs to scan the ephemeral public key registry to find the entire list of ephemeral public keys issued by anyone for any reason since the last scan.

It all relies on two uses of password spoofing. First, we need a pair of algorithms to generate the shared secret: one algorithm that uses Alice's secret thing (her ephemeral key) and Bob's public thing (his meta address), and another algorithm that uses Bob's secret thing (his root spend key) ) and Alice's public transaction (her ephemeral public key). This can be done in a number of ways; the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, one of the fruits that founded the field of modern cryptography, does exactly that.

But the shared secret alone is not enough: if we just generate a private key from the shared secret, then both Alice and Bob can spend from this address. We could stop there and have Bob transfer the funds to the new address, but that would be inefficient and unnecessarily reduce security. So we also added a key blinding mechanism: a pair of algorithms, Bob can combine the shared secret with his root spending key, Alice can combine the shared secret with Bob's meta address, so that Alice can generate stealth address, and Bob can generate a spending key for that stealth address, all without creating a public link between the stealth address and Bob's meta address (or between one stealth address and another).

first level title

Stealth addresses using elliptic curve cryptography

Stealth addresses using elliptic curve cryptography were first introduced by Peter Todd in 2014 in the context of Bitcoin. The technique works as follows (this assumes prior knowledge of basic elliptic curve cryptography; see here, here and here for some tutorials):

• Bob generates a secret key m and computes M = G * m, where G is the mutually agreed generation point of the elliptic curve. The invisible meta-address is the encoding of M.

• Alice generates a temporary key r, and publishes the temporary public key R = G * r.

• Alice can compute a shared secret S = M * r, and Bob can compute the same shared secret S = m * R.

• To compute the private key for this address, Bob (and Bob alone) can compute p = m + hash(S) which satisfies all our requirements above and is very simple!

There is even an EIP today that attempts to define a stealth address standard for Ethereum that both supports this approach and leaves room for users to develop other approaches (e.g. enabling Bob to have separate spending and viewing keys, or use different cryptography to achieve quantum-resistant security). Now you might be thinking: Stealth addresses are not hard, the theory is solid, adoption is just an implementation detail. The problem, however, is that a truly efficient implementation needs to go through some pretty big implementation details.

first level title

Stealth addresses and paying transaction fees

Suppose someone sends you an NFT. With your privacy in mind, they send it to a stealth address that you control. Your wallet will automatically discover this address after scanning the ephem public key on the chain. You are now free to prove ownership of this NFT or transfer it to someone else. But there is a problem! The account has 0 ETH, so transaction fees cannot be paid. Even ERC-4337 token payers won't work because they only work with fungible ERC 20 tokens. And you can't send ETH to it from your main wallet, because then you create a publicly visible link.

There is an "easy" way to solve this problem: just use ZK-SNARKs to transfer funds to pay fees! But this will consume a lot of gas, and a single transfer will cost hundreds of thousands of gas.

Another clever approach involves trusting specialized transaction aggregators (“seekers” in MEV lingo). These aggregators will allow users to pay once to purchase a set of "tickets" that can be used to pay for on-chain transactions. When a user needs to spend an NFT in a stealth address that contains nothing else, they provide the aggregator with one of their tickets, encoded using a Chaumian blinding scheme. This is the original protocol used in the centralized privacy-preserving electronic cash proposals proposed in the 1980s and 1990s. Seekers accept "tickets" and repeatedly include the transaction in their bundle for free until the transaction is successfully accepted in a block. Since the amount of funds involved is small and can only be used to pay transaction fees, the trust and regulatory issues are much lower than a "full" implementation of such a centralized privacy-preserving e-cash.

first level title

Stealth addresses and separate spending and viewing keys

Suppose instead of just having one master "root spend key" that does everything, Bob wants a separate root spend key and view key. Looking at the key can see all of Bob's stealth addresses, but cannot spend from them.

In the elliptic curve world, this can be solved using a very simple cryptographic trick:

• Bob's meta-address M is now of the form (K, V), encoded as G * k and G * v, where k is the spending key and v is the viewing key.

• The shared secret is now S = V * r = v * R, where r is still Alice's ephemeral key and R is still Alice's ephemeral public key.

• The public key of the stealth address is P = K + G * hash(S), and the private key is p = k + hash(S).

Note that the first clever encryption step (generating the shared secret) uses the viewing key, and the second clever encryption step (Alice and Bob's parallel algorithm generating the stealth address and its private key) uses the root spending key.

This has many use cases. For example, if Bob wants to receive POAPs, then Bob can give his POAP wallet (or even a less secure web interface) his viewing key to scan the chain and view all his POAPs without giving the interface Spend those POAP powers.

To more easily scan the entire set of ephemeral public keys, one technique is to add a view tag to each ephemeral public key. One way to do this in the above mechanism is to make the view label a byte of the shared secret (eg, the x coordinate of S modulo 256, or the first byte of hash(S)).

This way, Bob only needs to perform one elliptic curve multiplication for each ephemeral public key to compute the shared secret, and only 1/256 the time that Bob needs to do the more complex computation to generate and check the full address.

first level title

Stealth addresses and quantum-resistant security

The above scheme relies on elliptic curves, which is fine, but unfortunately vulnerable to quantum computers. If quantum computers become a problem, we will need to switch to quantum-resistant algorithms. There are two natural candidates: elliptic curve homology and lattices.

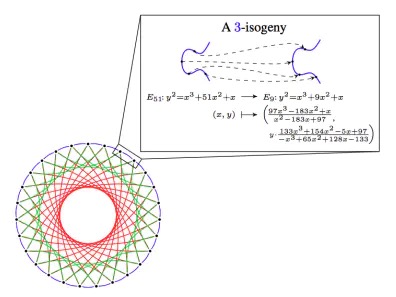

Elliptic curve homology is a very different mathematical construction based on elliptic curves that has linear properties that allow us to use similar cryptographic tricks to what we did above, but neatly avoids the construction that might be vulnerable to quantum computers discrete logarithms A cyclic group of attacks.

The main weakness of identity-based cryptography is its highly complex underlying mathematics, and the risk of possible attacks hidden under this complexity. In the last year, some homogeneous-based protocols were compromised, but others remain secure. The main advantages of homology are relatively small key sizes, and the ability to port directly to many elliptic curve-based methods.

3-homology in CSIDH, source here.

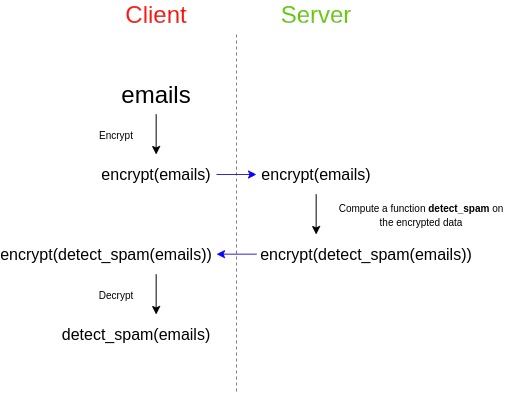

Lattices are a very different cryptographic structure that relies on much simpler mathematics than elliptic curve isomorphisms and is able to do some very powerful things (such as fully homomorphic encryption (FHE)). Stealth address schemes can be built on lattices, although designing the best scheme is an open problem. However, lattice-based structures tend to have larger key sizes.

Fully homomorphic encryption, which is an application of lattice. FHE can also be used to help the stealth address protocol in a different way: to help Bob outsource the calculation of the stealth address that checks whether the entire chain contains an asset, without revealing his view key.

A third approach is to build stealth address schemes from generic black-box primitives: basic ingredients that many people need for other reasons. The shared secret generation part of the scheme maps directly to the key exchange, which is an important component in public key encryption systems. The harder part is the parallel algorithm of having Alice generate only the stealth address (not the spending key) and Bob generating the spending key.

Unfortunately, you can't build a stealth address using simpler ingredients than what you need to build a public-key cryptosystem. There's a simple proof: you can build a public-key encryption system with a covert address scheme. If Alice wants to encrypt a message to Bob, she can send N transactions, each transaction is sent to either one of Bob's stealth addresses, or to one of her own stealth addresses, and Bob can see which transactions he has received to read Get news. This is important because there is mathematical proof that you can't do public key encryption with just hashes, and you can do zero-knowledge proofs with just hashes -- and therefore, stealth addresses can't be done with just hashes.

The encryption of c tells Bob nothing about anyone else, and k is a hash, so it reveals almost nothing about c. The wallet code itself only contains k, and c is private, meaning k cannot be traced back to h.

However, this requires a STARK, and STARKs are large. Ultimately, I think the post-quantum Ethereum world will likely involve many applications using many Starks, so I advocate an aggregation protocol like the one described here to combine all these Starks into one recursive Stark to save space.

first level title

Stealth addresses and social recovery and multi-L2 wallets

I've been a fan of social recovery wallets for a long time: wallets with a multi-signature mechanism whose keys are shared among institutions, your other devices, and your friends, some of which overwhelmingly can be recovered against access to your account unless you lose your master key.

However, social recovery wallets don't mix well with stealth addresses: if you have to restore your account (meaning, change the private keys that control it), you also have to perform some steps to change the account verification of your N stealth wallets Logically, this would require N transactions, at the expense of high fees, convenience, and privacy costs.

There are similar concerns with social recovery and the interplay of worlds of multiple layer 2 protocols: if you have an account at Optimism, Arbitrum, Starknet, Scroll, Polygon, and maybe some of those rollups have a dozen in parallel for scaling reasons instances, and you have an account on each instance, changing keys can be a very complex operation.

Changing the keys of multiple accounts in multiple chains is a huge amount of work.

This allows many accounts, even across many layer 2 protocols, to be controlled by a single value of k somewhere (on the base chain or some layer 2), where changing one value is enough to change the ownership of all accounts, all without would reveal the link between your accounts.

in conclusion

first level title

in conclusion