Vitalik: Why try to achieve finalization in a single slot?

Author: Vitallik Buterin

Special thanks to Justin Drake, Dankrad Feist, Alex Obadia, Hasu, and others for their feedback and comments on various versions of this post.

Currently, (beacon chain) Ethereum blocks take 64-95 slots (about 15 minutes) to achieve finalization. On the decentralization/finalization time/cost trade-off curve, it is reasonable to choose such a medium-length trade-off that is not bad in any dimension: 15 minutes is not too long, which is comparable to the confirmation time of current exchanges, and this Allows users to run nodes on regular computers, even with a large number of validators who have staked 32 ETH (instead of the earlier requirement of 1500 ETH). However, there are many good arguments for reducing finalization time to a single slot. This article is a research post evaluating some possible strategies for doing this.

01. How and why current Ethereum staking works

Currently, there are about 285,000 validators, and these accounts have deposited 32 ETH, so they can participate in Ethereum staking. The number of validators does not exactly correspond to the number of users (stakers) actually participating in staking: some wealthy stakers may control hundreds of validators. The minimum stake requirement of 32 ETH limits the number of possible validator accounts, ensuring that the Ethereum chain still has the computing power to process these accounts.

Every slot (12 seconds) a new block is added to the chain. In each slot, there are also thousands of attestations (submitted by validators) used to vote on the (beacon chain) chain head. There is a fork choice rule called LMD GHOST that takes these proofs as input to determine the head of the chain. This parallel voting by thousands of proofs makes Ethereum much more robust than traditional longest-chain systems: barring an active attack or a major network failure, even a single slot will almost always be unavailable. Will not be reversed (reverted).

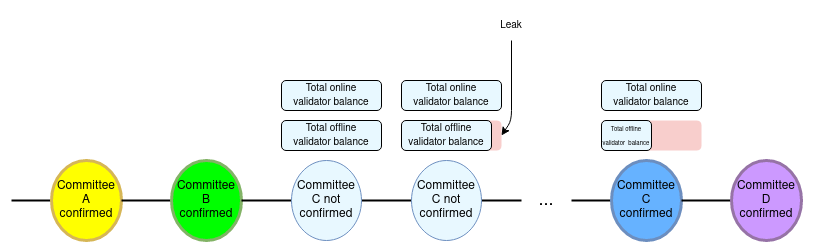

These proofs also serve a second purpose: they act as votes in a large-scale consensus algorithm called Casper FFG. Every epoch (every 32 slots is called an epoch, about 6.4 minutes), all active verifiers have the opportunity to make a proof. After two rounds, if all goes well, the previous epoch (and all blocks within it) will be finalized. Once a block is finalized, reversing that block would require at least 1/3 of all validators to destroy their deposits (stakes): the cost of the attack is over 3 million ETH.

Continuously censoring validators or transactions is also costly, although resistance to censorship attacks requires additional protocol intervention. If 51% of validators start censoring (validators or transactions), victims and users can coordinate a minority soft fork where they build on each other's blocks and ignore the attacker. On this handful of soft forks, the attacker's deposit would lose millions of ETH due to an inactivity leak, and the chain would resume finalization in a few weeks.

02. Why try to achieve finalization in a single Slot?

Try to change the status quo and shorten the finalization time to a single Slot. There are several key reasons for this:

user experience.Most users don't want to wait 15 minutes for finalization. Today, even exchanges often see user deposits as "finalized" after only 12-20 confirmations (about 3-5 minutes), although (compared to true PoS finalization) this offers 12-20 PoW confirmations are less secure. The finalization of a single slot will meet the speed that users are becoming more and more accustomed to, and at the same time provide a very high level of security.

Anti-MEV recombination.This articleThis article, for a more detailed exposition of this argument.

Opportunity to reduce protocol complexity and bugs.secondary title

Idea 1: Realize the finalization of a single slot through the "Super Committee"

Instead of all validators participating in each round of Casper FFG consensus, only a medium-sized super-committee (a medium-sized super-committee) composed of several thousand validators participates, allowing each round of consensus to be in a single Slot occur. Relevant technical ideas are first in this articleetheresear.ch postis introduced in .

This post goes into more detail about the idea, but the core principles are as follows:

Instead of running BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) consensus every epoch, it runs every slot. This means that once a transaction is included in a block, after one slot, the cost of reversing the transaction will be thousands of ETH.

We don't rely on all active validators to finalize a single slot. Instead, we rely on a randomly selected "super-committee" of several thousand validators to finalize individual slots.

image description

secondary title

Sub-benefits of shifting to "super committees"

Moving from global validators to supercommittees also has some incentive benefits:

Computational loads for running validator nodes have become more stable.The computing requirements of running a validator node no longer need to be proportional to the total number of validators, forcing the validator to have a powerful machine to cope with the large increase in the number of validators, but to make the computing load of running the validator node more stable, so that the verification users know exactly what computing needs they need.

Most of the time, validators can withdraw instantly.secondary title

How big must the supercommittee be?

The supercommittee should be "large enough to be a secure committee" in terms of the number of validators. But the committee must also be large enough in terms of its total ETH (i.e. the total stake of all validators in the committee). The amount of ETH slashed and sabotaged needs to be greater than what can actually be gained from the attack, and it needs to be large enough to deter or bankrupt a powerful attacker who has a huge external incentive to disrupt the chain.

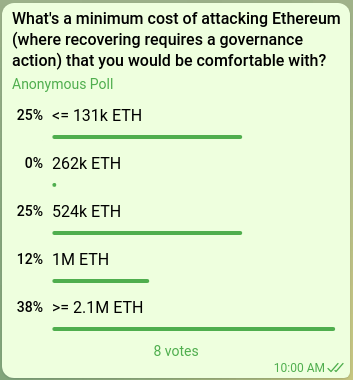

This question of how much ETH is needed is inevitably a matter of intuition. Here are some questions you can ask to guide your intuition:

Assuming the Ethereum chain is 51% attacked, it will take a few days for the community to coordinate an off-chain governance event to recover, but X % of ETH will be destroyed. How large does this X need to be to have a net benefit to the Ethereum ecosystem?

Let’s say a major exchange has had millions of ETH stolen, and the attacker staked the proceeds and gained more than 51% of the validator count. So how many 51% attacks can the validator have on the blockchain before all the stolen funds are destroyed (slashed)?

Suppose a 51% attacker starts repeatedly reorganizing the blockchain in a very short time to capture all MEV. What level of cost per second do we want the attacker to achieve?

image description

Above: Results of an internal survey of Ethereum researchers on "What do you think is the lowest cost to attack Ethereum?"

If we only focus on 51% attacks that do not rely on latency, then an attack cost of 1 million ETH would imply a "supercommittee" size of 2 million ETH (approximately 65,536 validators), if we also involve complex malicious A combined 34% attack on validators and network manipulation would result in a supercommittee size of 3 million ETH (approximately 97,152 validators). But if we want the load on the Ethereum chain to remain at today's levels (about 9,000 validators per slot, or about 288,000 ETH), this corresponds to an attack cost of 96,000 to 144,000 ETH. There is still a large gap between the two figures.

secondary title

Idea 2: Try to get as many attesters as possible to work

Suppose we really want a blockchain with a large number of validators participating in each slot (say, 131,072 validators per slot, which equates to a conservative 4 million ETH). So what will the performance numbers look like on that basis?

It turns out that having a large number of validators to prove that the on-chain cost per slot is not as high as it seems:

The state space required to store validator records will be exactly the same as today (about 150 bytes per validator).

Verifying a signature would require adding together a random subset of 131,072 public keys. Each elliptic curve addition can be done in about 1 microsecond, so this can be done in about 130 milliseconds. Each slot needs to be executed twice (possibly more if a block contains redundant proofs).

The on-chain addition cost can be further optimized if we assume that a validator active at slot N is usually also active at slot N+1; this means that for each slot, we only need to compute the Variable (delta), under good conditions, the aggregate public key may consist of thousands or even hundreds of validator public keys. You should always be able to do at least a 2x optimization (ie ~65 ms) even in the worst case.

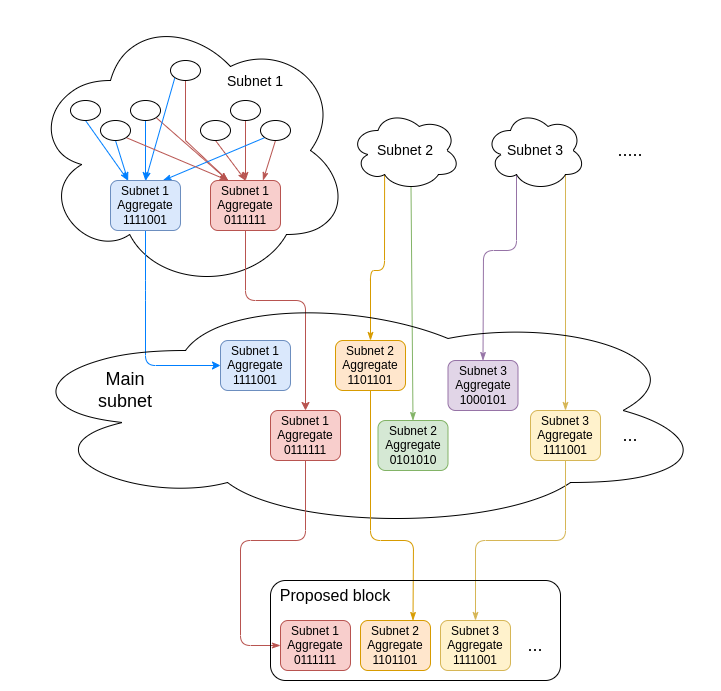

The biggest problem that remains issignature aggregation. There are 131,072 verifiers generating and sending signatures in a single Slot, and these signatures need to be quickly combined into a large aggregate signature.

Today, signature aggregation is done in p2p subnetworks. Each committee of 256 validators has its own subnetwork of signature aggregates. There are 16 randomly selected privileged aggregators who can aggregate signatures and submit them to the main subnet. The block proposer then takes the best signature aggregate from each committee and adds them together to form one large signature aggregate. As shown below:

This puts a load on each subcommittee, where validators need to verify signatures individually, especially in the event of an attack that floods the network with invalid signatures, and in a global subnet, if there are n committees, the proposer 16*n signatures must be verified.

Aggregation is likely to be the target of significant optimization over the next two years. Currently, the biggest bottleneck in practical applications is the load of each subnet, especially for nodes that need to be in multiple subnets.

Significant improvements can be obtained by two promising simple approaches:

Increase the number of subnets, to allow more total attestations without increasing the load on each subnet. The load on the main subnet will increase, but this can be compensated by dank-sharding, which allows all verifiers in a slot to sign the same data, improving efficiency and making these signatures easier to verify in batches.

Change network rules so that even nodes with many validators only need to participate in one subnetsecondary title

A more specialized aggregator

A possible more aggressive strategy to support more validators is to turn signature aggregation into a more specialized role (similar toBlock Builders in PBS (Proposer/Builder Split) Scheme), in this role we expect professional actors to be persistently present in each subnet (or even all subnets) and be able to collect signatures well. These participants can be paid or a voluntary role (since this additional cost is very low for users who have already staked many validators).

A simple protocol for this situation is to allow a verifier to sign a ProposedAggregate message containing (i) an aggregate signature, (ii) the participant's bitfields (16 kB assuming 131,072 verifiers), and (iii) The aggregator's signature on these two objects.

first level title

03. How do we achieve finalization in a single Slot?

Moving to single slot confirmations is a multi-year roadmap; even if a lot of development work starts soon, it will be after Ethereum completes PoS, sharding, and Verkle tree rollout. One of the major changes. In general, the implementation path is roughly as follows:

Step up work on optimizing proof aggregation.Regardless, this is an important question as the number of validators is expected to increase. We need more focused research and development efforts on this issue.

Agree on general parameters:How big are we aiming for the "supercommittee" (or will the size of the supercommittee be the set of all active validators and we implement some different mechanism to control how many active validators there can be)? What level of overhead is acceptable to us? What techniques will we use to reduce overhead?

In order to finalize a single slot, it is necessary to research, reach consensus and clarify an ideal consensus and fork selection mechanism.This would combine a BFT consensus mechanism (Casper FFG or another more traditional mechanism) with a fork choice rule where the fork choice rule only makes sense if ≥1/3 of the validators are offline.

Agree on a path to implementation and execute.This may require multi-step implementation, one of which introduces the super committee mechanism, and then adds a new consensus and aggregation mechanism in the next step.

The ultimate benefit of implementing finalization in a single slot would be significant, and the technology could improve over time to achieve other benefits not described in this paper (eg, using an increased maximum validator count to reduce the minimum ETH stake). Therefore, the technical challenges described in this article deserve deeper and more focused research and development to begin as soon as possible.