Only One in Ten Prediction Markets Will Survive to Year-End, Not an Exaggeration

- Core View: Prediction market making has a high barrier to entry, making liquidity construction difficult.

- Key Factors:

- The market making mechanism resembles an order book, requiring active management and carries high risk.

- Market volatility is intense and jumpy, prone to one-sided trends.

- Leading platforms have substantial capital, building moats through subsidies.

- Market Impact: Industry concentration will increase, making survival difficult for new projects.

- Timeliness Note: Medium-term impact.

Original | Odaily (@OdailyChina)

Author|Azuma (@azuma_eth)

There has been a lot of discussion on X in the past two days about the prediction market formula Yes + No = 1. The origin can be traced back to a detailed article by the influential figure DFarm (@DFarm_club) dissecting Polymarket's shared order book mechanism, which sparked a collective emotional resonance with the power of mathematics — original article link: "Demystifying Polymarket: Why Must YES + NO Equal 1?", highly recommended reading.

In the ensuing discussions, several influential figures including Lanhu (@lanhubiji) mentioned that Yes + No = 1 is another minimalist yet extremely powerful formula innovation following x * y = k, with the potential to unlock a trillion-dollar information flow trading market. I completely agree with this point, but I also feel that some discussions are overly optimistic.

The key lies in this point — "Anyone can add liquidity, become a market maker, earn trading fees, lower the participation barrier, and amplify liquidity." Many might think that Yes + No = 1 solves the barrier for ordinary people to become market makers, so prediction market liquidity will rise just like AMMs with x * y = k. However, the reality is far from it.

Prediction Markets Are Inherently More Difficult for Market Making

In practice, whether one can enter market making and build liquidity is not just a question of how to participate, but more importantly, an economic question of whether it can be profitable. Horizontally comparing to AMM markets based on the x * y = k formula, the difficulty of market making in prediction markets is actually much higher than the former.

For example, in a classic AMM market that strictly follows the x * y = k formula (like Uniswap V2), if I want to be a market maker for the ETH/USDC trading pair, I need to deposit both ETH and USDC into the pool in a specific ratio based on the real-time price relationship between the two assets in the liquidity pool. Subsequently, when that price relationship fluctuates, the amounts of ETH and USDC I can withdraw will fluctuate inversely (i.e., the familiar impermanent loss), but I can also earn trading fees. Of course, the industry later introduced many innovations around the basic x * y = k formula, such as Uniswap V3 allowing market makers to pursue a higher risk-reward coefficient by concentrating liquidity within specified price ranges, but the core model remains unchanged.

In this market-making model, if trading fees can cover the impermanent loss over a certain time frame (and often a longer time is needed to accumulate fees), it is profitable — as long as the price range is not too aggressive, I can be quite passive in market making, checking in occasionally when I remember. However, in prediction markets, if you try to market make with a similar attitude, the outcome will most likely be losing everything.

Using Polymarket as another example, let's first set up a basic binary market. For instance, if I want to market make in a market where "the real-time market price for YES is $0.58", I can place a buy order for YES at $0.56 and a sell order for YES at $0.60 — as DFarm explained in the article, this essentially means placing a buy order for NO at $0.40 and a sell order for NO at $0.44 — that is, providing order support at slightly wider specific points above and below the market price.

Now the orders are placed. Can I just leave them and forget? When I check next time, I might see one of the following four scenarios:

- Both orders remain unfilled;

- Both orders have been filled;

- One side's order has been filled, and the market price remains within the original order range;

- One side's order has been filled, but the market price has deviated further away from the remaining order — for example, bought YES at $0.56, the sell order at $0.60 is still there, but the market price has dropped to $0.50.

So, which scenario is profitable? I can tell you that in low-frequency attempts, different scenarios may lead to different profit/loss outcomes, but in a real-world environment, consistently operating with such passivity will ultimately result in losses. Why is that?

The reason is that prediction markets do not follow the liquidity pool market-making logic of AMMs but are closer to the order book market-making model of CEXs. Their operating mechanisms, operational requirements, and risk-reward structures are completely different.

- In terms of operating mechanism, AMM market making involves depositing funds into a shared liquidity pool for collective market making. The pool disperses liquidity across different price ranges based on the x * y = k formula and its variants. Order book market making requires placing specific buy and sell orders at specific price points; liquidity support exists only where orders are placed, and execution must happen through order matching.

- In terms of operational requirements, AMM market making only requires depositing both sides of the token pair into the pool within a specific price range, and it remains effective as long as the price stays within that range. Order book market making requires active and continuous order management, constantly adjusting quotes to respond to market changes.

- In terms of risk-reward composition, AMM market making primarily faces impermanent loss risk, earning fees from the liquidity pool. Order book market making faces inventory risk during one-sided market moves, with profits coming from the bid-ask spread and platform subsidies.

Continuing with the assumption from the earlier case, knowing that my main risk in market making on Polymarket is inventory risk, and profits mainly come from the bid-ask spread and platform subsidies (Polymarket provides liquidity subsidies for orders near the market price in some markets, see the official homepage for details), the potential profit/loss situations for the four scenarios are as follows:

- First scenario: No bid-ask spread profit, but can receive liquidity subsidies;

- Second scenario: Already profited from the bid-ask spread, but no longer receives liquidity subsidies;

- Third scenario: Has taken on a position in YES or NO (i.e., inventory risk), but can still receive some liquidity subsidies under certain conditions;

- Fourth scenario: Similarly has become a directional position, the position is already at a floating loss, and no longer receives liquidity subsidies.

Two additional points need attention here. First, the second scenario actually always evolves from the third or fourth scenario, because often only one side's order gets filled first, thus it temporarily becomes a directional position. The risk just didn't materialize, as the market price reversed and triggered the order on the other side. Second, compared to the relatively limited market-making profits (spread profits and subsidy amounts are often fixed), the risk of a directional position is often unlimited (the upper limit is that the held YES or NO tokens become worthless).

In summary, if I want to make money consistently as a market maker, I need to capture profit opportunities as much as possible and avoid inventory risk — so I must actively optimize my strategy to maintain the first scenario as much as possible, or quickly adjust the order range after one side's order is triggered to turn it into the second scenario, avoiding being stuck in the third or fourth scenario for long.

Doing this well consistently is not easy. Market makers need to first understand the structural differences of different markets, comparing subsidy intensity, volatility, settlement time, judgment rules, etc. Then, they need to track or even predict market price changes more accurately and quickly based on external events and internal capital flows. Subsequently, they must actively adjust orders promptly according to changes, while also designing and managing inventory risk in advance... This clearly exceeds the capability range of ordinary users.

A Wilder, More Volatile, Less Predictable Market

If it were only like this, it might still be okay. After all, the order book mechanism is not new; it remains the mainstream market-making mechanism on CEXs and Perp DEXs. Active market makers in these markets could theoretically migrate their strategies to prediction markets to continue profiting while injecting liquidity into the latter. However, reality is not that simple.

Let's think about this question together: What is the situation market makers fear the most? The answer is simple — one-sided markets, because one-sided markets tend to continuously amplify inventory risk, breaking through portfolio balance and causing huge losses.

However, compared to traditional cryptocurrency trading markets, prediction markets are inherently a wilder, more volatile, and less predictable place. One-sided markets always appear more exaggerated, more abrupt, and more frequently.

"Wilder" means that in conventional cryptocurrency trading markets, when viewed over a longer timeline, mainstream assets still exhibit a certain oscillating trend, with upward and downward trends often rotating in cycles. In prediction markets, the trading instruments are essentially event contracts. Each contract has a clear settlement time, and the Yes + No = 1 formula dictates that ultimately only one contract's value will become $1, while the other options will become zero — this means that bets in prediction markets will eventually end in a one-sided market starting from a certain point in time. Therefore, market makers need to design and execute inventory risk management more strictly.

"More volatile" means that fluctuations in conventional trading markets are determined by the continuous博弈 of sentiment and capital. No matter how剧烈 the波动, its price changes are continuous, leaving reaction space for market makers to adjust inventory, control spreads, and dynamically hedge. But fluctuations in prediction markets are often driven by discrete real-world events; price changes are often discontinuous — the price might be at 0.5 one second, and a piece of real-world news could directly push it to 0.1 or 0.9 the next second. Often, it's very difficult to predict at which time and due to which event the market will drastically change, leaving market makers with极小 reaction time.

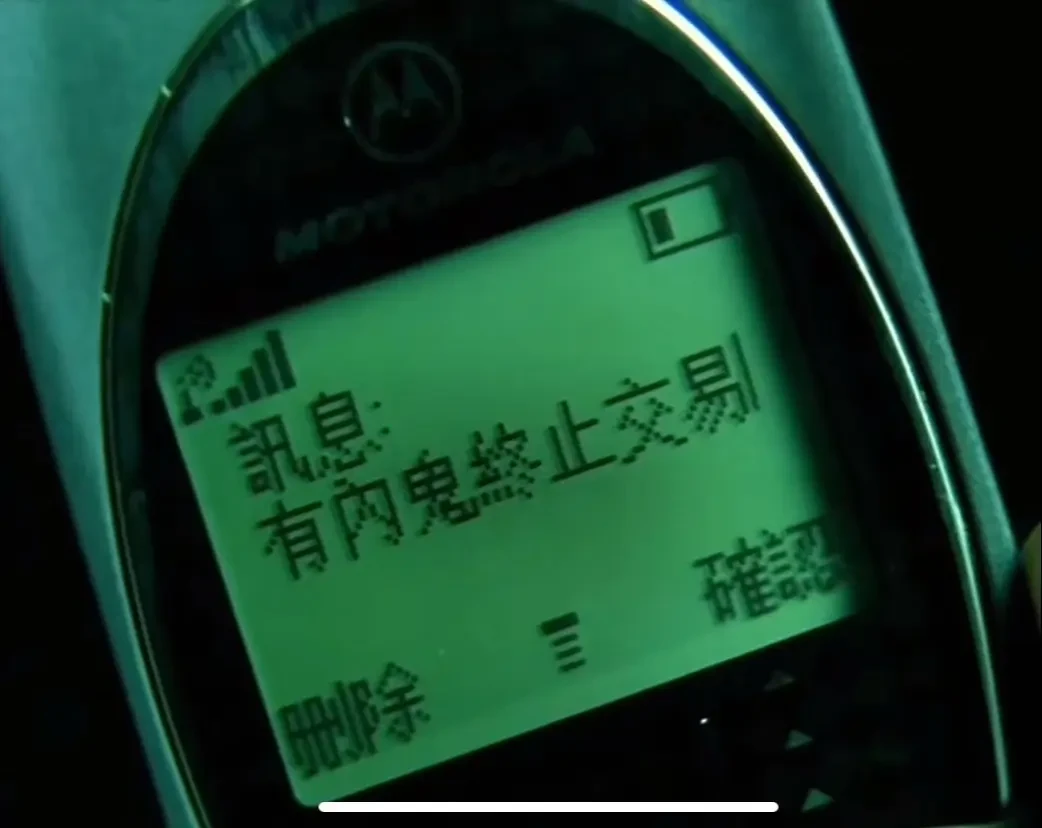

"Less predictable" means that there are many insider players in prediction markets who are close to information sources or are the sources themselves. They are not coming to博弈 with trading opponents based on predictions about future market movements but are coming with明确 results to harvest — in front of these players, market makers are naturally at an information disadvantage, and the liquidity they provide becomes the channel for these insiders to cash out. You might ask, don't market makers have inside information? This is a typical paradox. If I already knew inside information, why would I bother market making? I'd just bet on the direction directly and make more money.

It is precisely because of these characteristics that I have long agreed with the statement that "the design of prediction markets is structurally unfriendly to market makers" and strongly advise ordinary users against轻易 trying market making.

So, is there no profit to be made in prediction market making? That's not entirely true either. Luke, founder of Buzzing (@DeFiGuyLuke), once disclosed that based on market experience, a relatively稳健 expectation is that market makers on Polymarket can earn roughly 0.2% of trading volume as profit.

So, frankly, this is not an easy way to earn yield. Only professional players who can accurately track market changes, timely adjust order status, and effectively execute risk management can sustain operations over longer time cycles and earn money through real skill.

The Prediction Market Sector May Struggle to See a Hundred Flowers Bloom

The difficulty of market making in prediction markets, on one hand, imposes higher requirements on market makers' capabilities, and on the other hand, poses a challenge for platforms in building liquidity.

The difficulty of market making implies constraints on liquidity construction, which directly反馈 to users' trading experience. To address this issue, leading platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi have chosen to spend real money on liquidity subsidies to attract more market makers.

Nick Ruzicka, an analyst focused on the prediction market sector, cited a Delphi Digital research report in November 2025 in an article, stating that Polymarket has invested approximately $10 million in liquidity subsidies, at one point paying over $50,000 daily to attract liquidity. As its leading position and brand效应巩固, Polymarket has significantly reduced subsidy intensity, but on average, it still subsidizes $0.025 for every $100 in trading volume.

Kalshi has a similar liquidity subsidy program and has spent at least $9 million on it. Additionally, Kalshi leveraged its compliance advantage in 2024 (Odaily Note: Kalshi is the first prediction market platform licensed by the CFTC; Polymarket also obtained a license in November 2025) to sign a market-making agreement with the top-tier Wall Street market-making service provider Susquehanna International Group (SIG),极大 improving the platform's liquidity状况.

Whether in terms of available capital reserves or compliance barriers, these are real moats for leading platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi — a few months ago, Polymarket just accepted a $2 billion investment from ICE, the parent company of the NYSE, at an $8 billion valuation, and there are reports of planning another round of financing at a valuation exceeding $10 billion. On the other hand, Kalshi has also completed a $300 million financing round at a $5 billion valuation. Both leading players now have相当充裕 ammunition reserves.

Currently, prediction markets have become a hot创业 topic in the entire market, with various new projects emerging constantly. However, I am not very optimistic. The reason is precisely that the龙头效应 in prediction markets is actually stronger than many imagine. In the face of continuous real-money subsidies from leaders like Polymarket and Kalshi and their降维级 partners from the compliant world, what can new projects use to compete head-on? How much capital do they have to耗 with them? It's not impossible that some new projects backed by真爸爸 can爆金币, but clearly not every one is.

Haseeb Qureshi, the big光头 from Dragonfly, posted his predictions for 2026 a few days ago. He wrote, "Prediction markets are growing rapidly, but 90% of prediction market products will be completely ignored and gradually disappear by the end of the year." I don't know his reasoning, but I agree this is not alarmist talk.

Many are期待 a百花齐放 in the prediction market sector and畅想着 profiting from it based on past experience, but this scenario may be difficult to materialize. If you really want to bet, it's better to focus directly on the leaders.