Replaying 1929: The Historical Cycle of Bitcoin Treasury Companies and Investment Trusts

- 核心观点:比特币财库公司与1920年代投资信托泡沫高度相似。

- 关键要素:

- 两者均依赖资产净值溢价和杠杆放大收益。

- 均通过金融炼金术创造投机性证券。

- 反身性循环推高泡沫后加速崩溃。

- 市场影响:警示比特币生态系统性风险。

- 时效性标注:中期影响。

Original author: Be Water

Original translation: TechFlow

Speculative Attacks Part 3

Roaring 20s

In financial markets, frenzy often has powerful vested interests, even when it borders on madness—as was the case in 1929. This should serve as a cautionary tale for anyone commenting on or writing about current financial market trends. However, there are fundamental rules in these matters that cannot be ignored, and the cost of ignoring them is far from negligible. Those who scorn all current warnings often suffer the most.

—JK Galbraith, “Parallels to 1929,” The Atlantic Monthly, January 1987, before the 1987 Crash

While Bitcoin treasury companies are currently just a minor blemish in the vast financial matrix—and, with Fartcoin's market capitalization at $1.5 billion, even examining them closely seems absurd—their similarities to the investment trusts of the 1920s reveal recurring speculative pathologies that transcend their current scale. In fact, they provide a universal blueprint for pervasive reflexive bubbles. Therefore, the shared mechanisms between trusts and treasury companies offer a perfect lens through which to understand the broader dynamics of financial history and the current financial matrix.

In Part 1 of The Speculative Attack , we explored how Michael Saylor’s MicroStrategy weaponized Wall Street’s own financial engineering against the traditional financial system by subverting the alchemy of risk ; now hundreds of companies are racing to copy his blueprint.

Part Two of "Speculative Attack" explores the parallels between today's Bitcoin Treasury companies and the "investment trusts" of the 1920s. These trusts began as distorted versions of revered British investment vehicles , but were gradually corrupted by American financiers through leverage. By mid-1929, trust mania reached its peak. Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation became the "MicroStrategy" of its time, and new trusts were launched at a rate of one per day, fueled by investor enthusiasm, willing to pay double or even triple the value of the underlying "scarce" assets.

Yet, how could a futuristic concept like the Bitcoin Treasury Company possibly have anything to do with the financial trusts of the 1920s? Back then, computers weren't commonplace, let alone blockchains, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) hadn't even been established, let alone begun to curb the frivolous abuses of Wall Street. At first glance, the structural differences between the trusts of 1929 and the treasury companies of today seem both obvious and inevitable.

We believe these differences are inherently unimportant. Each era in financial history has exhibited its own unique characteristics within its own unique context. Excessive focus on superficial distinctions has long rationalized reasonable warnings about emerging financial risks and excesses, informed by historical lessons. Market participants treat each event as if it were humanity's first encounter with financial alchemy , ignoring the "warning to posterity" documented in The Great Mirror of Folly (1720). However, this approach is tantamount to preparing for the last war rather than striving to master enduring principles of warfare and apply them to the current battle.

In recent decades, this pattern has been particularly evident across a range of sectors, from "private credit" to trillions of dollars in negative-yielding bonds to the historic (and now seemingly unwinding) real estate bubbles in Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Market participants have dismissed concerns about these real estate bubbles by citing the lack of complex American-style derivatives (such as CDOs and NINJA loans), rampant fraud, non-recourse lending, and bank failures during the 2008 financial crisis. Like purists who insist that champagne must come from a specific French slope, many now believe that only the hallmarks of the subprime mortgage crisis popularized by "The Big Short"—including CDO cubic managers eating sushi in Las Vegas—can be considered a genuine real estate bubble.

Excerpt from the movie "The Big Short"

The result is a kind of historical literalism: structural differences are seen as evidence of security, when in fact they are often exaggerated, misleading, or simply irrelevant. For example, in practice, each of the above countries has simply developed its own unique mechanisms, which function like alchemy.

Bitcoin Treasury proponents make a similar argument, arguing that comparisons to 1920s investment trusts are fundamentally flawed: those trusts were built on opaque pyramid structures, hidden leverage, and unregulated market fees, while Bitcoin Treasury companies are transparent single-entity companies with no management fee layer, subject to modern SEC disclosure rules, and holding currently desirable market-valued assets. In short, they argue that any superficial similarities mask profound differences in structure, agency relationships, and information flows.

While we agree with some, if not all, of these points, we nonetheless arrive at different conclusions. What's striking isn't the stark differences between Bitcoin Treasury companies and the trusts of the 1920s, but rather the recurring fundamental dynamics that make their deeper similarities impossible to ignore. Both feature large premiums to net asset value, "magic" appreciation, and reflexive feedback loops where purchases drive up the price of the underlying asset, thereby increasing their own value and borrowing power. Investors in both eras embraced "smart" long-term leverage and the alluring promise of easy money through financial alchemy to capitalize on "sure-win" bets.

These patterns represent more than just historical parallels; they reveal the enduring invariants of human nature and financial reflexivity that are at the root of credit bubbles, transcending time and asset classes. The fate of these early trusts thus provides an objective lens through which to examine not only the emerging Bitcoin Treasury company phenomenon, but also the recurring financial alchemy that has defined bubble formation for centuries.

Twitter/X: @bewaterltd . Have a suggestion? Feedback is always welcome.

Not investment advice. For educational/information purposes only. See disclaimer.

" Investment trusts are multiplying like locusts "

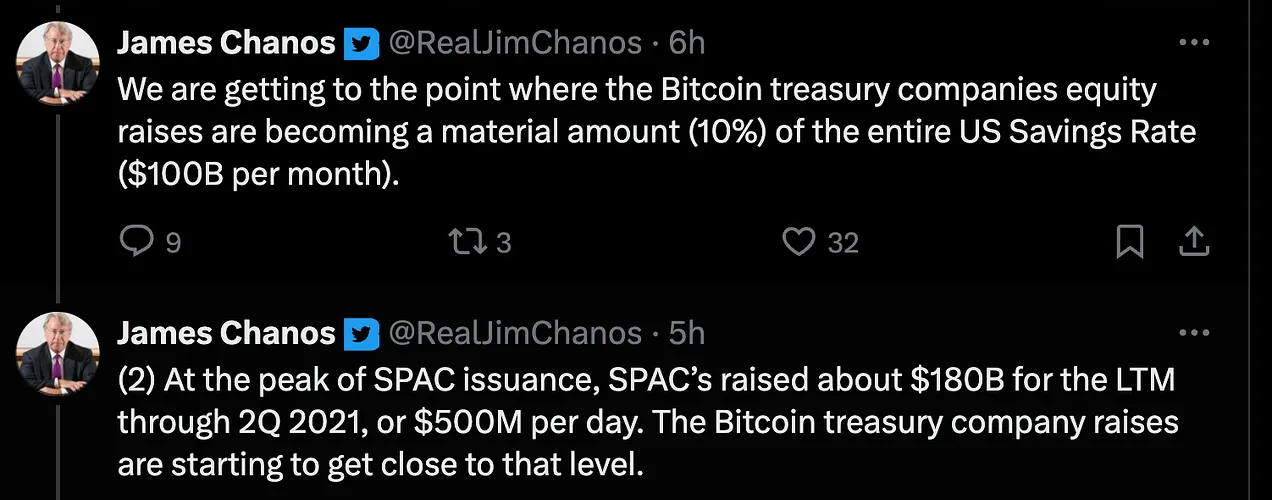

The explosive growth of Bitcoin treasury companies mirrors the growth of investment trusts in the 1920s. Both gold rushes were fueled by a perfect storm of greed: intense investor demand for scarce assets created a premium to net asset value, and promoters rushed to liquidate it. If Goldman Sachs could rake in massive profits from its trusts in the 1920s, why couldn't other firms do the same? If MicroStrategy can liquidate its net asset value premium, why shouldn't others follow suit?

JK Galbraith documented the explosive growth of trusts in the 1920s:

An estimated 186 investment trusts were established in 1928. By early 1929, these were being established at a rate of about one per business day , for a total of 265 investment trusts established throughout the year.

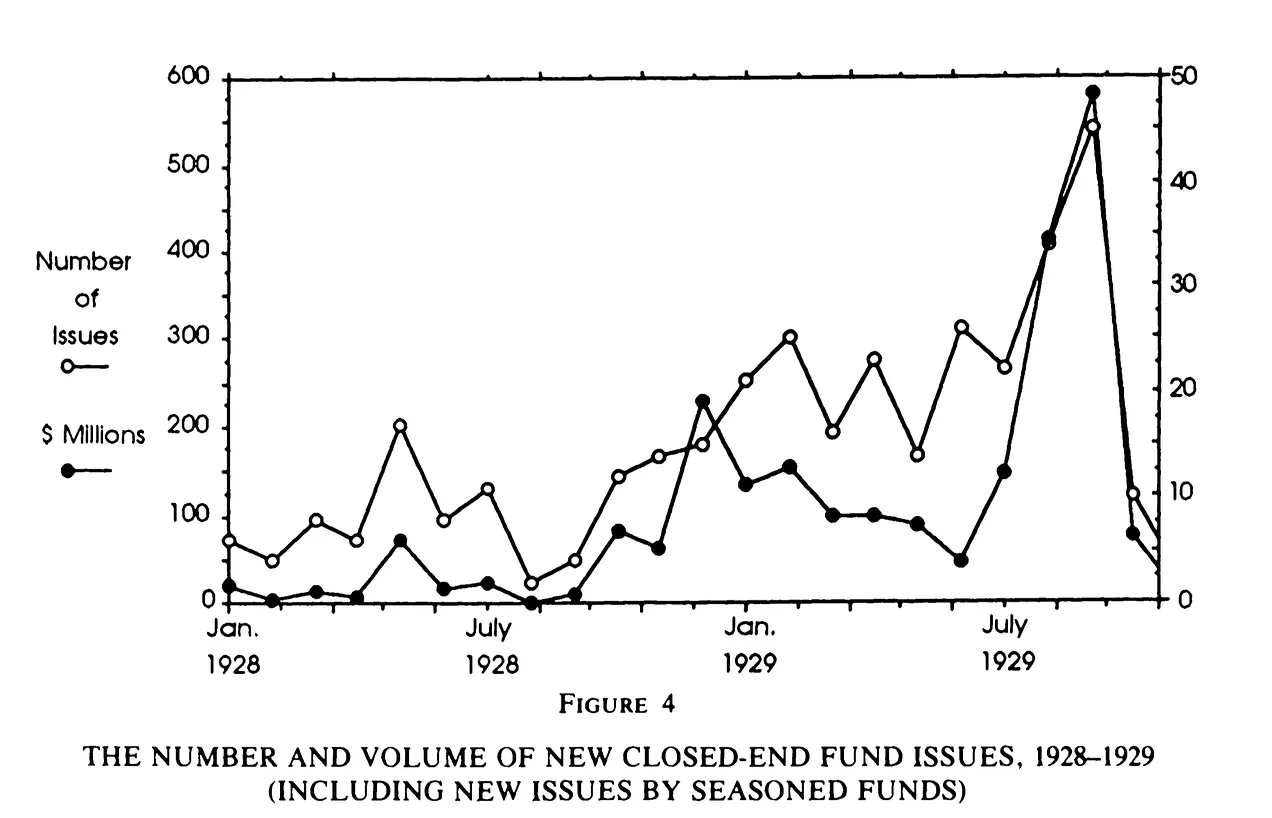

The amount of money raised was equally impressive, representing 70% of all funds issued in the 1920s. In August and September 1929 alone, new trust issuances totaled $1 billion—equivalent to $20 billion at today’s purchasing power parity, or $130 billion of today’s economy:

In 1927, these trusts sold about $400 million worth of securities to the public. In 1929, they sold an estimated $3 billion worth of securities. This represented at least one-third of all new capital issued that year.

By the fall of 1929, total assets of the investment trusts were estimated to be over $8 billion, an increase of about eleven times since the beginning of 1927.

Source: DeLong/Shleifer

Frederick Lewis Allen's account corroborates JK Galbraith's account; in The Days of yore: An Informal History of the 1920s , Allen vividly describes how "investment trusts multiplied like locusts":

There are now said to be nearly five hundred such trusts, with a total paid-in capital of about $3 billion and holdings of about $2 billion in stock—many of which were purchased at present high prices. These trusts include both honest and shrewdly managed companies and wildly speculative enterprises started by ignorant or greedy promoters.

The Cambrian Explosion of Bitcoin Treasury Companies

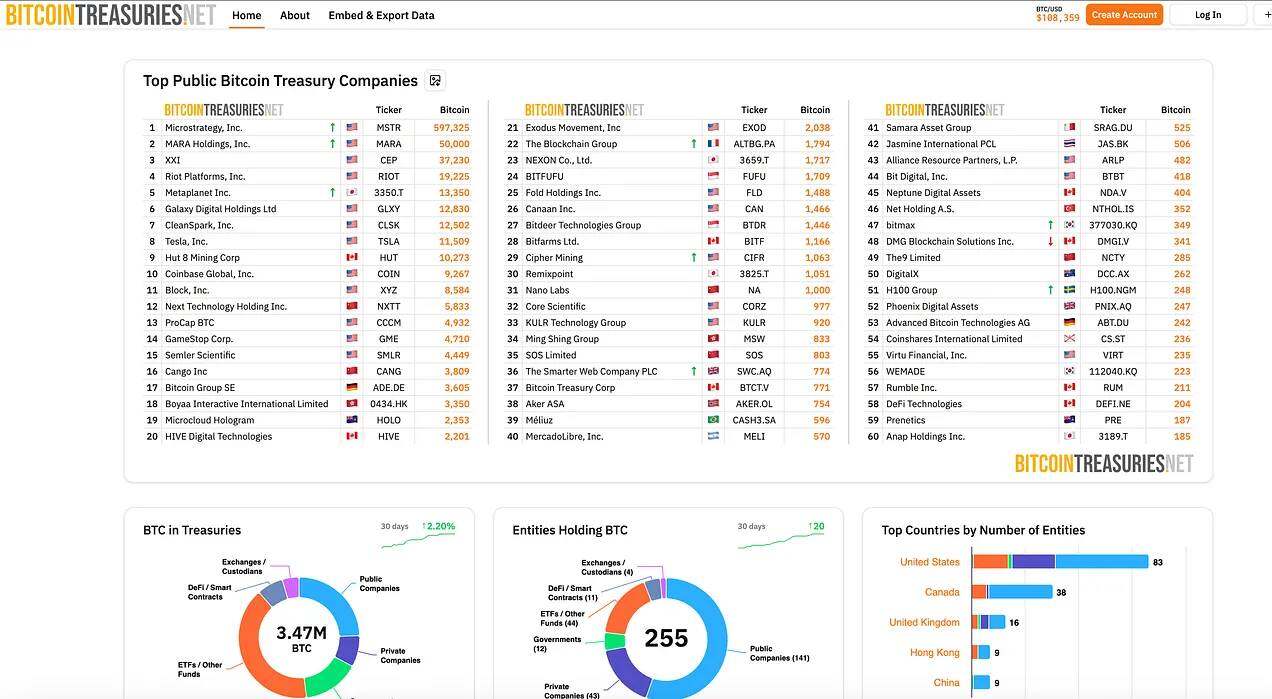

Today, Bitcoin Treasury companies are exhibiting a strikingly similar pattern; new entities are launching weekly as companies around the world race to replicate MicroStrategy’s success. This “Cambrian explosion” of Bitcoin Treasury companies can be tracked in real time via the web dashboard:

Source: BitcoinTreasuries.net

The Golden Age of Scams

What began as innovation quickly devolved into exploitation. JK Galbraith and Frederick Lewis Allen emphasized that this was not an era of individual bad actors but rather an era of systemic opportunism driven by soaring prices and a lack of ethics.

The most profitable role in the trust boom is not the investor, but the promoter. JK Galbraith clearly points out that insiders, through the fees they collect, can capture value both upfront and over time, while public buyers bear the ultimate risk:

The public's enthusiastic embrace of investment trust securities has yielded the greatest returns. Almost without exception, people are willing to pay a premium significantly above the issue price. The sponsoring company (or its sponsors) typically receives a quota of shares or warrants entitling them to purchase shares at the issue price. They then immediately sell them at a profit at the higher market price.

New shares are typically offered to insiders or favored clients at a slight premium to net asset value, but many quickly rise to significant premiums. For example, Lehman Brothers Corporation's offering at $104 per share was significantly oversubscribed, effectively purchasing $100 worth of assets (note, however, that its management contract stipulated that a 12.5% profit be paid to Lehman Brothers as a management fee; the fund's true net asset value was likely only $88). Upon public trading, the fund's share price immediately soared to $126. The organizers not only profited from the $4 per share price difference and future high management fees but also became significant initial investors on terms better than the public. Furthermore, they retained the right—worthless when the fund trades at a discount but invaluable when it trades at a premium—to collect management fees in the form of new shares purchased at current net asset value.

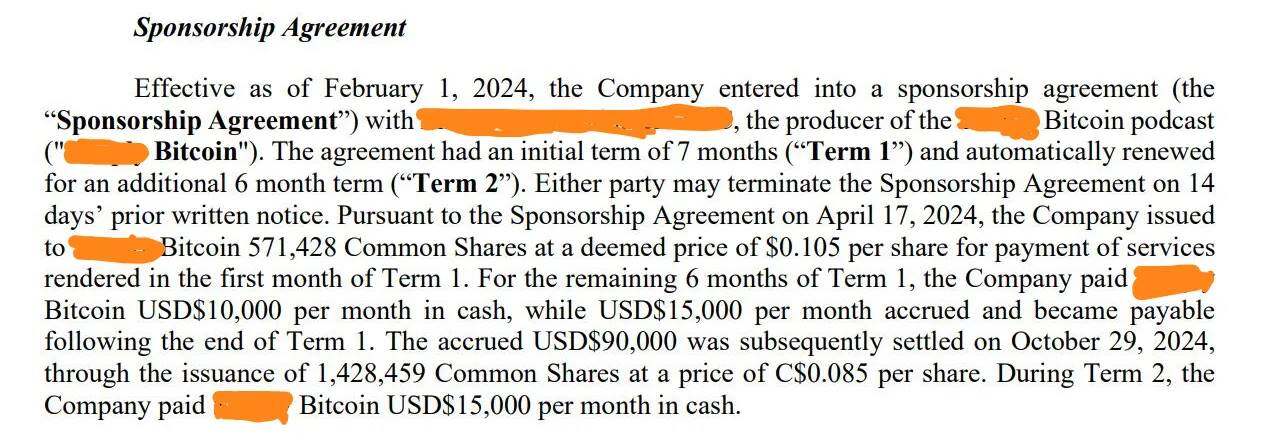

Similar to the trusts of the 1920s, today's Bitcoin treasury companies often employ similar arrangements—founder stock grants, internal stock options, and incentive programs for promoters and podcasters. This time, however, these mechanisms are publicly disclosed under SEC rules designed to address the abuses of the 1920s. But transparency can neither eliminate risk nor dispel incentive distortions:

The speculative frenzy and rapid pace of trust company formation in the 1920s provided excellent cover for abuses by ill-intentioned promoters. The proliferation of illicit investment trusts and holding company structures exemplified what J.K. Galbraith considered the financial excesses of the 1920s. He noted that American businesses had "admitted an extraordinary number of promoters, corrupt officials, swindlers, imposters, and frauds," describing the phenomenon as "a flood of corporate theft." Frederick Lewis Allen agreed:

As long as prices rose, people could indulge in all kinds of questionable financial behavior with peace of mind. The bull market concealed countless sins. For the promoters, it was a golden age, and "his" name was too numerous to mention.

These observations resonate with other periods of frenzied financial speculation and fraud, including today’s “ Golden Age of Swindle ,” as well as historical episodes like John Law’s Mississippi Bubble—discussed in our “ Alchemy of Risk ” series and wryly documented in The Great Mirror of Folly (1720). But behind the outright fraud lies another kind of risk—perhaps less obvious, but no less dangerous: the structural risk alchemy inherent in the design of trust capital structures.

Financial Alchemy

Some call it alchemy, I call it valuation.

—Phong Le, CEO of MicroStrategy

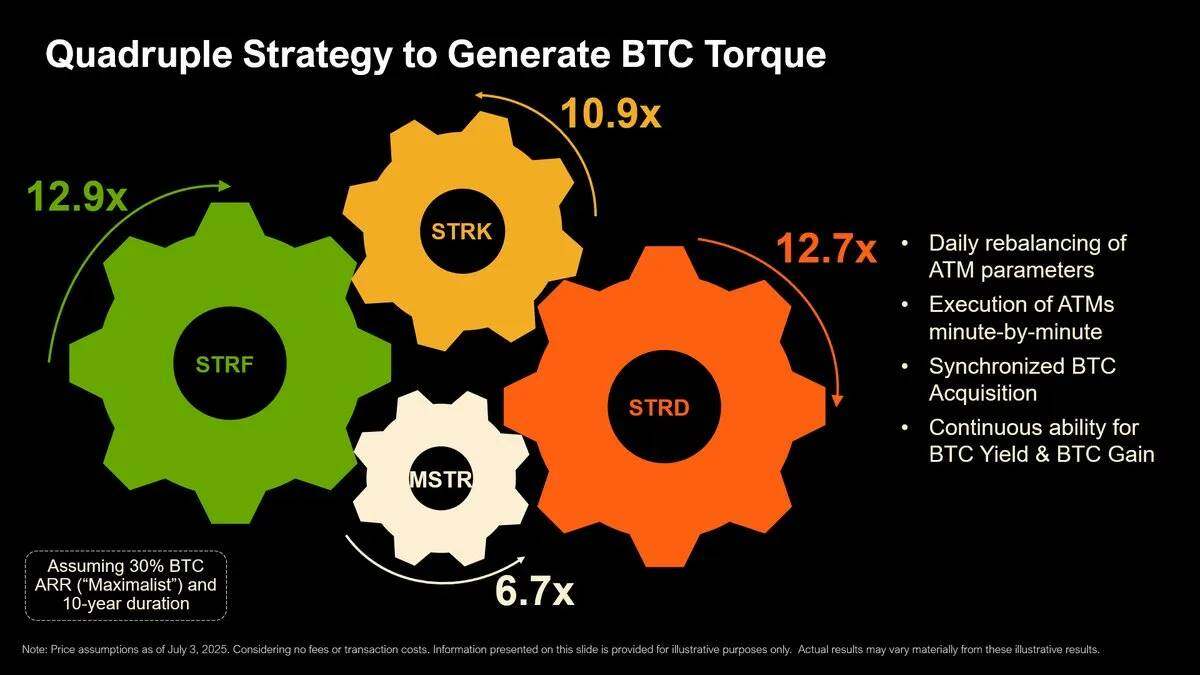

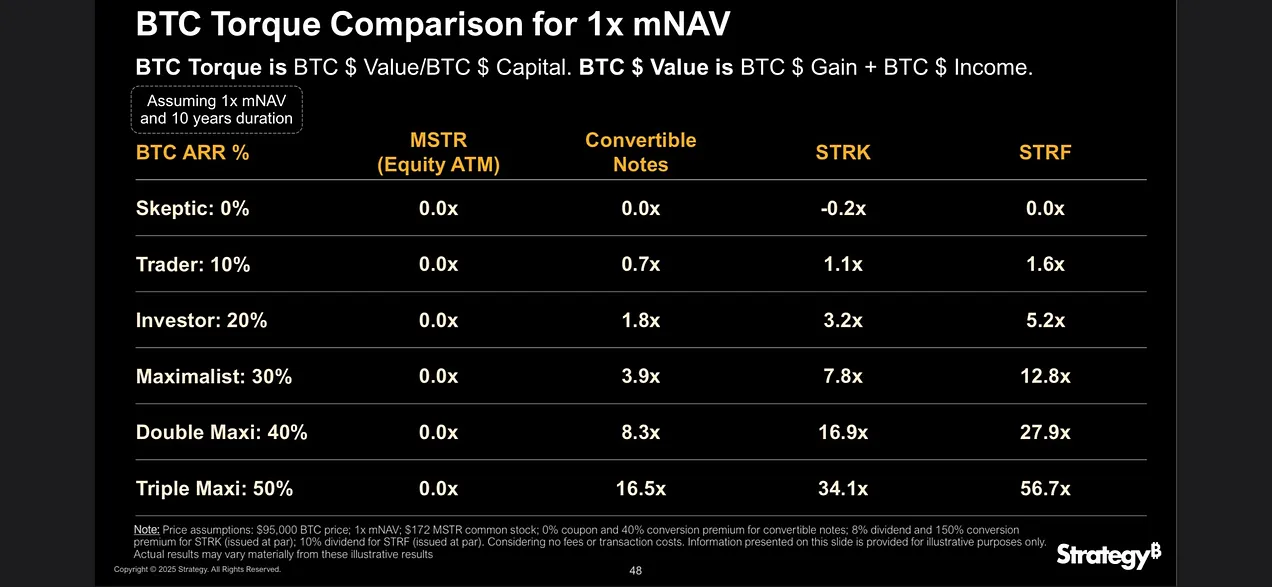

Source: MicroStrategy

MicroStrategy provided a video and table showing the “leverage effect” of the different layers of its capital structure (equity, convertible bonds, preferred stock, etc.) — essentially, the amplified exposure to Bitcoin price movements:

Michael Saylor refutes the comparison to closed-end funds like GBTC (see part two here), noting that MicroStrategy has greater flexibility as an operating company:

Sometimes I see... an analyst on Twitter say, "Oh, this is just like when GBTC and Grayscale's P/E ratios fell below 1x mNAV. What they're missing is that Grayscale (GBTC) is a closed-end fund. We're an operating company."

[A fund like GBTC]…does not have the operational flexibility to manage its capital structure…It does not have the option to refinance or assume leverage or sell securities, buy securities, recapitalize or repurchase its own stock.

An operating company like MicroStrategy has greater flexibility. We can buy stock, sell stock, recapitalize, and even take on debt to fill or address funding gaps.

However, this distinction ignores a certain historical irony: the investment trusts of the 1920s pioneered the capital structure innovations that make today’s Bitcoin Treasury companies so attractive to investors, and created in the 1920s the same reflexive dynamics that we observe today.

As JK Galbraith documented, the investment trust has evolved into something far more complex than a simple collective investment vehicle like GBTC – it has become a flexible corporate structure of the kind Michael Saylor touts today:

An investment trust effectively becomes an investment company. It sells its securities to the public—sometimes just common stock, more often a combination of common stock, preferred stock, bonds, and other types of debt instruments—and management then invests the proceeds as it sees fit. By selling non-voting shares to common shareholders or transferring their voting rights to a voting trust controlled by management, common shareholders are prevented from interfering with any potential management actions.

The Investment Company Act of 1940 explicitly restricted these practices precisely because they had proven so effective—and so dangerous—in market speculation leading up to the Great Crash of 1929. When Greyscale and its lawyers structured GBTC, they likely chose this form, at least in part, to avoid registration under the '40 Act (the Investment Company Act of 1940) . The inability of funds like GBTC to deploy MicroStrategy's full suite of tools isn't an inherent limitation, but rather a deliberate policy of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to prevent a repeat of the excesses and consequences of the investment trusts of the 1920s.

The capital structure of the trusts of the 1920s is nearly indistinguishable from that of MicroStrategy today: both issue securities—stock, bonds, convertible bonds, and preferred stock at a premium to their mNAV—to attract investors with varying risk (“leverage”) preferences and return demands. For example, the convertible bonds at the heart of MicroStrategy’s financing strategy are also a hallmark of the trusts of the 1920s documented by Frederick Lewis Allen in his research:

It became fashionable to convert new bonds issued by the trust into shares or attach warrants to buy shares at some future time, giving them an acceptable speculative flavor.

During the 1929 boom, the business model of many investment trusts was rooted less in asset management than in financial alchemy. Complex capital structures and layers of leverage were not merely passive financing tools to boost returns; they were the core of the enterprise. Their goal was to create a continuous supply of speculative securities to satisfy an insatiable public demand. This demand was driven by the belief—captured by J.K. Galbraith—that the underlying stocks the trusts purchased had acquired a certain "scarcity value" and that the most sought-after stocks were about to disappear from the market.

Yet, the public isn’t simply buying a diversified portfolio of scarce stocks; it’s betting on the trusts’ own financial alchemy: the real “products” are the trusts’ own securities and net asset values. They act like alchemical laboratories, transforming the public’s desire for speculative returns into new securities conjured out of thin air.

Smart long-term debt

This MicroStrategy-like strategy allowed trust managers in the 1920s to access high-quality leverage: long-term corporate bonds (sometimes as long as 30 years), rather than margin loans or “call” loans that needed to be liquidated immediately. In theory, these extended maturities allowed trusts to maintain leverage throughout the business cycle without facing immediate refinancing pressures, while their relatively low yields reflected widespread investor complacency and systemic mispricing of risk.

Lyn Alden makes a similar observation about contemporary Bitcoin treasury companies:

Publicly listed companies have access to better leverage than hedge funds and most other types of capital. Specifically, they have the ability to issue corporate bonds…typically with maturities of many years. If they hold Bitcoin and the price declines, they don't have to sell prematurely. This makes them more resilient to market fluctuations than entities relying on margin lending. While some bearish scenarios could still force company liquidations, these scenarios would result in a more prolonged bear market and are therefore less likely to occur.

Long-term debt and reflexivity

Lyn’s analysis, while accurate for any given company, ignores the systemic risks that can arise when these “safer” leverage structures proliferate. Just as 30-year mortgages failed to prevent the 2008 financial crisis, no amount of long-term debt can inherently eliminate systemic risk and may even exacerbate it.

During the boom of the late 1920s, financial alchemy amplified returns through the same self-fulfilling prophecy that Bitcoin Treasury companies benefit from today: rising asset prices and mNAV premiums led to greater leverage and "leverage," which in turn drove up asset prices even further. But this reflexive cycle made the system inherently unstable. As we've seen, these complex capital structures were far more than passive financing vehicles—they played an integral role in fueling both the bubble's spectacular expansion and its subsequent collapse.

Just as cheap hurricane insurance fueled a building boom after several quiet storm seasons, the seeming safety of regularly maturing debt in a bull market can encourage increased leverage, creating larger positions and asset inflation that ultimately amplifies rather than dampens downside volatility. Newly discovered "affordable" forced liquidation protections triggered a spectacular expansion of risk-taking along the coast—until the inevitable hurricane arrived and the insurance market itself collapsed. When hundreds of companies with the same capital structure and business model engage in speculative "one-way bets," what appears individually prudent can easily become collectively destabilizing. In financial "progress," the dose is the difference.

Path Dependence and Pyramid Schemes

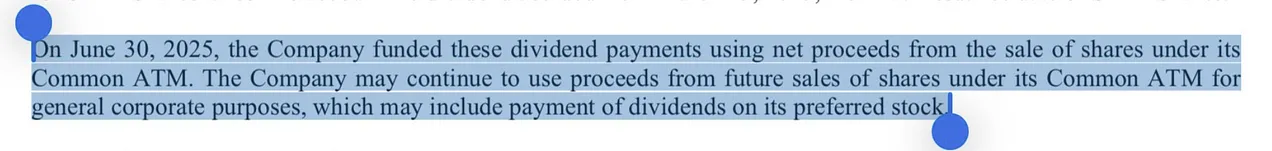

Like some of the extreme mortgages of 2005-2006 that were so designed they were almost guaranteed to default on the first payment, many investment trusts near the end of the 1920s bubble were, from the outset, variations on pyramid schemes—reliant on new inflows or price increases to meet their obligations—despite holding diversified portfolios of dividend-paying stocks and interest-paying bonds:

Some of these companies…are so well capitalized that they cannot even pay preferred stock dividends out of the income from their securities holdings and must rely almost entirely on the hope of profitability.

This creates an unstable dependency: To pay bondholders and preferred shareholders, the trust must either issue new shares (reliant on its mNAV premium) or count on future portfolio appreciation. These two mechanisms are intertwined: portfolio gains drive up the mNAV premium, which in turn encourages the issuance of more shares to fund further portfolio expansion.

Essentially, they use new investors’ money or future price appreciation to repay existing debt – a classic pyramid scheme structure – which leaves them vulnerable to market downturns when new capital dries up and portfolio returns evaporate, causing their mNAV premiums to collapse in a self-reinforcing spiral.

Since Bitcoin Treasury companies have no cash flow (yet), they tend to follow a similar strategy of raising capital from investors to pay down debt:

Similar to the trusts of the 1920s, this pyramiding strategy works effectively while Bitcoin appreciates, the companies maintain their net asset value (mNAV), and the capital markets remain open to them. However, if all of these conditions deteriorate simultaneously over an extended period of time—perhaps due to overextended, leveraged Bitcoin treasury companies themselves—these companies will face the same structural vulnerabilities that devastated the trusts of the 1920s.

Indeed, a key difference between the investment trusts of the 1920s and today’s Bitcoin Treasury companies lies in the assets they actually hold. These trusts held (seemingly) diversified portfolios of dividend-paying stocks and interest-paying bonds, and the cash flows from these portfolios funded the repayments of their preferred stocks and bonds—at least during the Great Depression, when they were correlated due to the widespread credit bubble.

While "hyperbitcoinization" and "Bitcoin banks" may change this dynamic in the future, Bitcoin currently generates no cash flows, pays no dividends, and earns no interest. This creates a structural vulnerability that the trusts of the 1920s, for all their flaws, never faced. Bitcoin treasury companies lack even the revenue streams of the 1920s trusts, making them more susceptible to these pyramid dynamics, not less. Even in the context of a secular bull market where Bitcoin appreciates tenfold, their viability depends entirely on their path: on sustained appreciation, access to credit, and investor enthusiasm. A break in this chain—perhaps due to oversaturation of leveraged Bitcoin treasury companies themselves—ultimately leads to structural collapse, which we will discuss in the upcoming fourth part of this series.

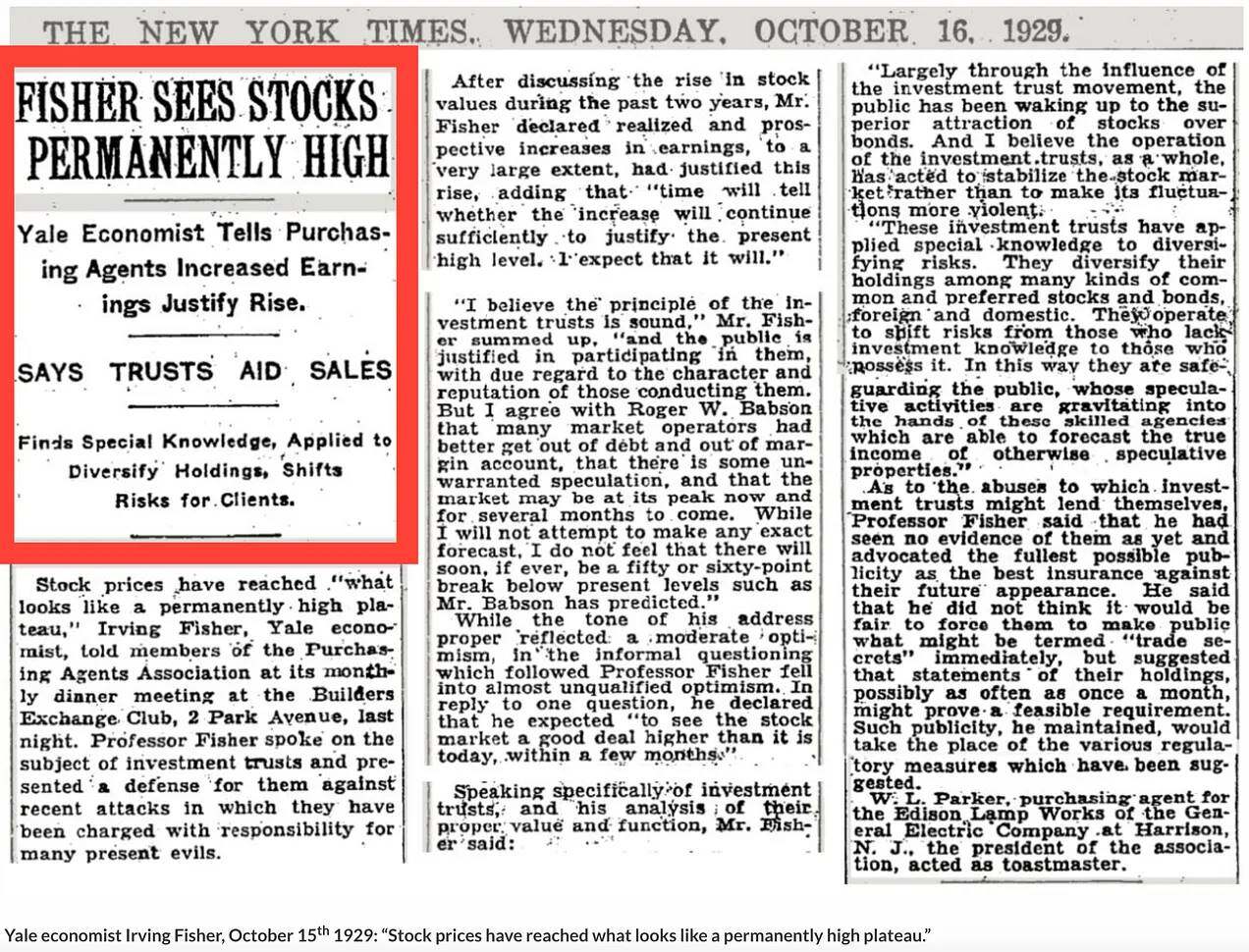

The collapse of the trusts and the financial crash of 1929

Renowned Yale economist Irving Fisher famously said that stock prices had reached a "permanently high level" on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash. Fisher's statement captured the euphoric confidence that often characterizes market tops. Even the most ardent Bitcoin bulls should be wary of such sweeping statements, at least in the short term:

Irving Fisher's famous quote about the market "high" is now well-known, but its lesser-known context reveals a deeper story. He was essentially defending investment trusts as a vital underpinning of stock valuations, much like Bitcoin supporters today point to the built-in demand for Bitcoin treasury companies. The New York Times reported at the time:

Professor Irving Fisher spoke on the subject of investment trusts and defended them against recent attacks that blame them for many of the current ills.

Irving Fisher defended the trusts on the grounds that these vehicles are awakening people to the advantages of stocks over bonds and providing investors with superior structures for gaining equity exposure — just as Bitcoin fund advocates claim today that MicroStrategy provides greater “leverage” than directly holding Bitcoin, which itself has advantages over traditional financial assets (TradFi) such as fiat currencies, stocks, bonds, and real estate:

I believe the principles of investment trusts are sound, and public participation in them is justified, but due consideration must be given to the character and reputation of the managers. It was largely due to the investment trust movement that the public gradually realized that stocks were more attractive than bonds. And I believe that, overall, the operation of investment trusts has helped stabilize the stock market, not exacerbate its volatility.

Reflexivity works both ways!

The stock market crash was more than just a price event—the forces that fueled the stock market boom amplified the decline in asset markets and the real economy as the reflexive cycle reversed. The investment trusts that Irving Fisher had championed just a week earlier, claiming they would guarantee “permanently high” stock values, were now the primary drivers of the crash:

By now, it was obvious that investment trusts, once considered the pillars of economic prosperity and the built-in defense against collapse, were now a profound weakness. The enthusiasm, even the fervor, for leverage that had been talked about just two weeks earlier had completely reversed.

It wiped out the entire value of a trust's common stock with astonishing speed. As before, let's consider the situation of a typical small trust. Assume that the company's public securities had a market value of $10 million at the beginning of October. Half of this was common stock, and half was bonds and preferred stock. These securities were fully covered by the current market value of the trust's holdings. In other words, the market value of the securities contained in the trust's portfolio was also $10 million.

A representative portfolio of securities held by such a trust would have lost perhaps half its value by early November. (By later standards, many of these securities were still quite valuable; on November 4th, Tel and Tel's lowest share price was $233, General Electric's $234, and Steel's $183.) The new portfolio, worth $5 million, would barely cover the losses on the bonds and preferred stock. The common stock would be wiped out. Beyond its pessimistic outlook, it was now worthless. This geometric cruelty wasn't isolated. Instead, it had a disproportionate impact on the shares of leveraged trusts. By early November, shares in most of these trusts were practically unsaleable. Worse still, many of these trusts' shares traded over-the-counter or off-the-counter exchanges, where buyers were scarce and market activity was thin.

Frederick Lewis Allen's account reaffirms JK Galbraith's statement:

Yet, the fear didn't linger for long. With the price structure collapsing, a sudden rush to the exits erupted. By 11 a.m., traders on the stock exchange were frantically scrambling to "sell." Long before the lagging ticker could predict the situation, phone and telegraph reports of the impending market bottom had arrived, and sell orders were doubling. Leading stocks dropped two, three, even five points between sell-offs. Down, down, down... Where were the bargain hunters who should have stepped in at a time like this? Where were the investment trusts who were supposed to cushion the market by buying new shares at low prices? Where were the big market makers who professed their bullish stance? Where were the powerful bankers who were supposed to be able to prop up prices at any moment? There seemed to be no support. Down, down, down. The clamor from the exchange floor had become a roar of panic.

Therefore, we should never forget that reflexivity works both ways and affects not only the market price of the underlying asset, but also the fundamentals of the underlying asset:

The most significant weakness of corporations lies in their new structure of vast holding companies and investment trusts. Holding companies control vast swathes of the utilities, railroads, and entertainment industries. Like investment trusts, these sectors are subject to the ever-present risk of devastating reverse leverage. In particular, dividends from operating companies are used to pay interest on the bonds of upstream holding companies. A halt in dividends means bond defaults, bankruptcy, and the collapse of the structure. Under these circumstances, the temptation to cut investment in operating plants in order to maintain dividends is clearly strong. This exacerbates deflationary pressures. Deflation, in turn, depresses profits and leads to the collapse of the corporate pyramid. When this occurs, further layoffs become inevitable. Revenues are diverted exclusively to repaying debt, making borrowing for new investment impossible. It is hard to imagine a corporate system more suited to perpetuating and exacerbating a deflationary spiral...

Stock market crashes are also an extremely effective way to exploit weaknesses in corporate structures. Operating companies at the end of the holding company chain are forced to retrench due to the stock market crash. The subsequent collapse of these systems, along with the investment trusts, effectively destroys both the ability to borrow and the willingness to invest and lend. What long appeared to be a pure trust effect quickly translates into declining orders and rising unemployment.

The crisis not only destroyed paper wealth, but also exposed bad investments in the real economy that were masked by debt-driven asset price inflation and forced a painful liquidation of unsustainable business models and debt structures.

Even in the context of a structural secular bull market, Bitcoin Treasury companies face the same risks. If Bitcoin were to decline significantly (perhaps due to excessive leverage and speculation by the treasury companies themselves), and the asset were to trade at a prolonged discount to net asset value, the common shares could be wiped out, much like the trust shares were in 1929, despite their "safe" leverage. Furthermore, as we will discuss in Part IV, the proliferation and subsequent collapse of Bitcoin Treasury companies could even negatively impact the adoption of Bitcoin itself for a period of time.

Born in mNAV, died in mNAV

If we are an operating company and we are trading at a discount to net asset value, then we can monetize it - that is a good thing for me.

Michael Saylor’s confidence in monetizing the discount to NAV (which may itself be justifiable for MicroStrategy) reflects the same logic that trust managers used to justify buybacks in the 1920s, only to find that this support strategy was ineffective when liquidity across the ecosystem disappeared and selling pressure dominated.

These trusts discovered that buying back shares as investors sold off and credit tightened was very different from issuing shares as investors bought in. To support the share price, these trusts began buying back shares at a discount to net asset value—a strategy likely employed by Bitcoin Treasury, but with similarly disappointing results for most:

The stabilizing effect of the investment trusts' vast cash reserves has also proven illusory. In early autumn, the investment trusts had abundant cash and liquidity... But now, as the effects of reverse leverage become apparent, the investment trusts' management is more concerned about the plummeting value of their own shares than about adverse fluctuations in the overall stock market...

In this situation, many trust companies are desperately using their available cash to prop up their own stocks. However, there's a huge difference between buying stocks now when the public wants to sell and buying them last spring (as Goldman Sachs did)—then the public's desire to buy drove up the stock price, creating competition. Now, cash is flowing out, and stock is flowing in, with either no noticeable impact on the stock price or a short-lived one. What seemed like a brilliant financial strategy six months ago has now become financial self-immolation. Ultimately, a company buying its own stock is the exact opposite of selling it. Companies typically grow by selling their stock.

As the crisis deepened, mNAV continued to trade at a discount, and trusts burned through their remaining cash reserves in a desperate (and ultimately self-defeating) attempt to prop up plummeting share prices:

However, these effects were not immediate. If a person was a financial genius, belief in their genius did not vanish immediately. For the battered yet unbowed genius, backing their own company's stock still seemed a bold, imaginative, and effective path. In fact, it seemed the only option to avoid a slow but inevitable death. So, given the financial constraints, the trust company's management opted for a faster but equally inevitable demise. They purchased stock that was worthless to them. People are often deceived by others. The autumn of 1929 was perhaps the first time people deceived themselves on such a large scale.

in conclusion

The investment trust mania of the 1920s provides a broad blueprint for understanding financial bubbles built on leverage, reflexivity, and the magic of premium/net asset value growth. What began as a financial innovation quickly evolved into a speculative tool, promising easy riches through financial alchemy. When the music stopped, the same reflexive mechanisms that had propelled prices to euphoric heights accelerated their catastrophic decline.

There are striking parallels with Bitcoin Treasury companies today—from the proliferation of new physical entities, to their reliance on a premium to net asset value, to their use of long-term debt to amplify returns. As we explored in "Tower of Babel," the primary root cause of the 2008 financial crisis wasn't the subprime crisis, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and mortgage fraud—and the primary cause of the collapse of the investment trusts of the 1920s wasn't fraud, bad bets, a lack of transparency and regulatory oversight, or their sometimes intertwined or pyramidal holdings. They collapsed because their success—built on the " alchemy of risk" —inherited the seeds of future failure; Bitcoin Treasury companies may be following the same path, heading towards the same precipice.

More worryingly, however, just as the trusts of the 1920s signaled the speculative excesses of that era, Bitcoin Treasury companies are symptomatic of today’s “multiple inflations”—a deeper malady distorting the current economic order. The emergence of a recently filed gold treasury company suggests that Saylor and Bitcoin Treasury companies’ speculative assault on fiat currencies is expanding beyond Bitcoin:

This broader assault on monetary orthodoxy may signal the beginnings of a "flight from real value" (Flucht in die Sachwerte)—a wave that could escalate into an all-out war against financial institutions. Indeed, the Gold Treasury Company's actual business model—tokenizing commodity markets—could accelerate this trend by channeling even more capital and credit into the real economy. Far from containing inflationary pressures safely within the virtual casino of the financial matrix, this could further exacerbate the inflationary supercycle.

Next up: Can Bitcoin break the curse of reflexivity?

In Part 4, we will explore whether Bitcoin’s unique monetary properties—confronted with the unprecedented scale of central bank money printing—might enable leveraged money firms to perform a game of financial jujitsu that completely reverses the historical dynamic: triggering a reflexive speculative attack on fiat currencies and creating a self-fulfilling prophecy akin to a bank run. Or, similar to the investment trusts of the 1920s, will they, within their very structure, sow the seeds of systemic vulnerability in the Bitcoin ecosystem.