Exiting the Liquidity Machine: Inside the Pumpfun Token Launch

Original author: Pine Analytics

Original translation: GaryMa Wu talks about blockchain

summary

This report investigates a widespread and highly coordinated meme token farming pattern on Solana: token deployers transfer SOL to “sniper wallets”, enabling them to buy the token in the same block as the token is listed. By focusing on clear, provable funding chains between deployers and snipers, we identify a set of high-confidence extractive behaviors.

Our analysis shows that this strategy is neither an isolated phenomenon nor a fringe activity — in the past month alone, over 15,000 SOL in realized profits have been extracted from over 15,000 token issuances in this way, involving over 4,600 sniping wallets and over 10,400 deployers. These wallets exhibit an unusually high success rate (87% of sniping profits), clean exits, and a structured operating model.

Key findings:

Deployer-sponsored sniping is systematic, profitable, and often automated, with sniping activity most concentrated during U.S. business hours.

Multi-wallet farming structures are very common, often using temporary wallets and coordinated exits to simulate real demand.

· The obfuscation methods are constantly upgraded, such as multi-hop funding chains and multi-signature sniping transactions, to evade detection.

Despite its limitations, our one-hop funding filter still captures the clearest, most repeatable examples of “insider” behavior at scale.

This report proposes a set of actionable heuristics to help protocol teams and front-ends identify, flag, and respond to such activity in real time — including tracking early position concentrations, tagging deployer-associated wallets, and issuing front-end warnings to users on high-risk issuances.

While our analysis covers only a subset of same-block sniping activities, their scale, structure, and profitability suggest that Solana token issuance is being actively manipulated by a coordinated network and that existing defenses are insufficient.

Methodology

This analysis started with a clear goal: to identify behaviors on Solana that indicate coordinated meme token farming, specifically where deployers are funding hacked wallets on the same block as the token launch. We divided the problem into the following phases:

1. Filter the same block sniping

We first filter for wallets that were sniped in the same block after deployment. Due to: Solana has no global mempool; the addresses of tokens must be known before they appear on the public frontend; and the extremely short time between deployment and first DEX interaction. This behavior is almost impossible to occur naturally, so "same-block sniping" becomes a high-confidence filter to identify potential collusion or privileged activity.

2. Identify the wallet associated with the deployer

To distinguish between highly skilled snipers and coordinated “insiders”, we tracked the SOL transfers between deployers and snipers before the token went live, and only marked wallets that met the following conditions: directly received SOL from deployers; directly sent SOL to deployers. Only wallets with direct transfers before the launch were included in the final dataset.

3. Linking sniping to token profits

For each sniping wallet, we map its trading activities on the sniped token, specifically calculating: the total amount of SOL spent on buying the token; the total amount of SOL sold on DEX; and the realized net profit (not nominal profit). This allows us to accurately attribute the profit extracted from the deployer of each sniping.

4. Measuring size and wallet behavior

We analyze the scale of such activities from multiple dimensions: the number of independent deployers and sniper wallets; the number of confirmed coordinated same-block sniping; the distribution of sniping profits; the number of tokens issued by each deployer; and the reuse of sniper wallets across tokens.

5. Traces of machine activity

To understand how these operations work, we grouped sniping activity by UTC hour. The results show a concentration of activity in specific time windows, with a significant drop-off in the late evening UTC hours, suggesting that this is more of a cron job or manual execution window aligned to the United States than a global, continuous automation.

6. Exit Behavior Analysis

Finally, we study the behavior of the deployer's associated wallets when selling the targeted tokens: measuring the time between the first purchase and the final sale (holding time); counting the number of independent sell transactions used by each wallet to exit. This allows us to distinguish whether the wallet chooses to liquidate quickly or sell gradually, and examines the correlation between exit speed and profitability.

Focus on the clearest threats

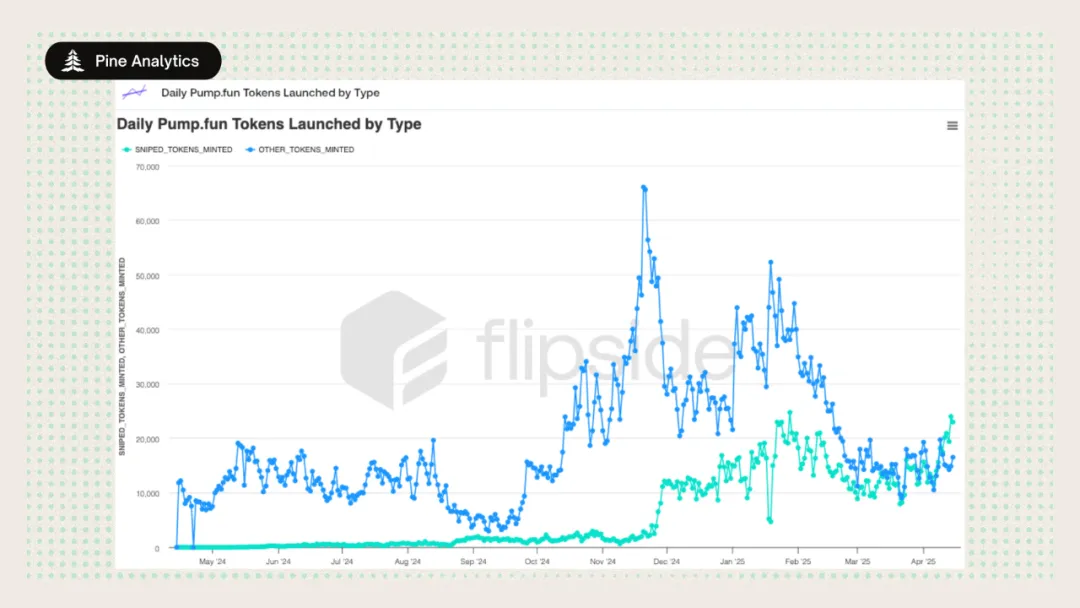

We first measured the scale of same-block sniping in the pump.fun issuance and the results were shocking: over 50% of tokens were sniped in the creation block — same-block sniping has gone from a fringe case to a dominant issuance pattern.

On Solana, same-block participation typically requires: pre-signed transactions; off-chain coordination; or deployers and buyers sharing infrastructure.

Not all same-block sniping is equally malicious, and there are at least two types of actors: “cast-the-net” bots — testing heuristics or small-scale speculation; and coordinated insiders — including deployers who fund their own buyers.

To reduce false positives and highlight true coordinated behavior, we added strict filtering to the final indicator: only sniping with direct SOL transfers between the deployer and the sniping wallet before launch is counted. This allows us to confidently lock in: wallets directly controlled by the deployer; wallets acting under the command of the deployer; wallets with internal channels.

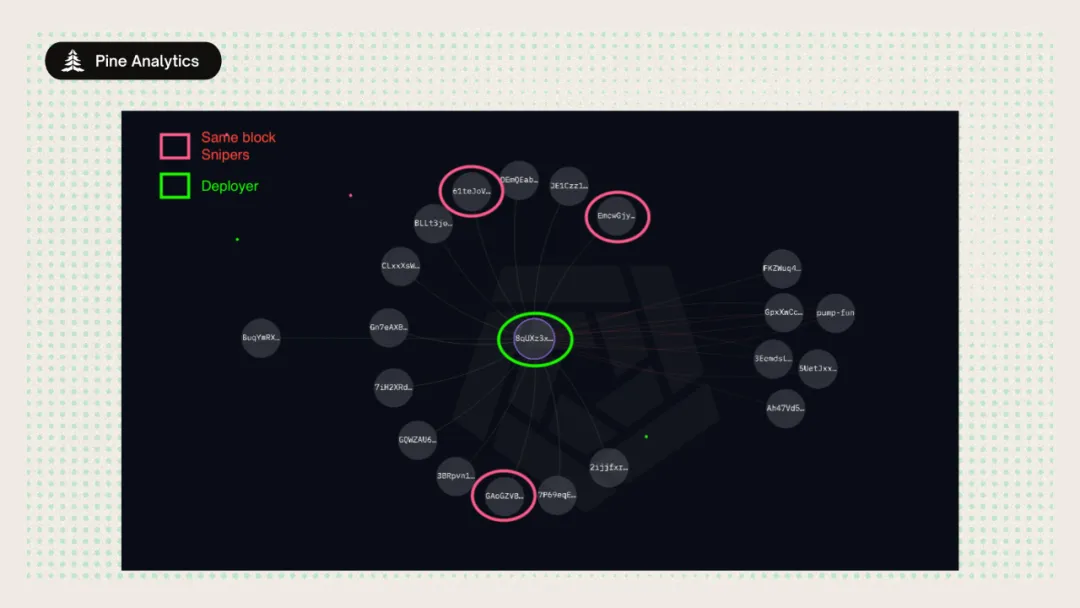

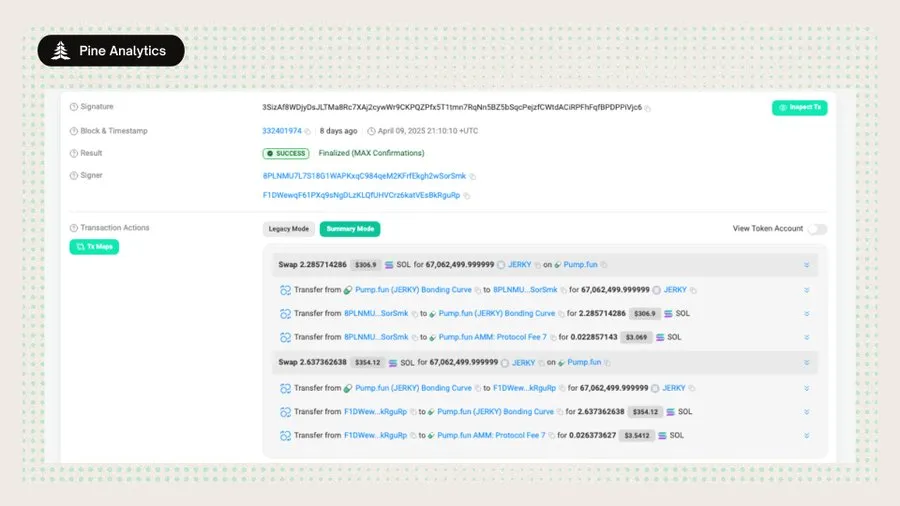

Case study 1: Direct funding

The deployer wallet 8qUXz3xyx7dtctmjQnXZDWKsWPWSfFnnfwhVtK2jsELE sent a total of 1.2 SOL to 3 different wallets, and then deployed a token called SOL > BNB. The 3 funded wallets bought the tokens in the same block they were created, before they were visible to the wider market. They then quickly sold their profits, performing a coordinated flash exit. This is a textbook example of farming tokens through pre-funded sniping wallets, and is directly captured by our funding chain method. Although the technique is simple, it is performed at scale across thousands of issuances.

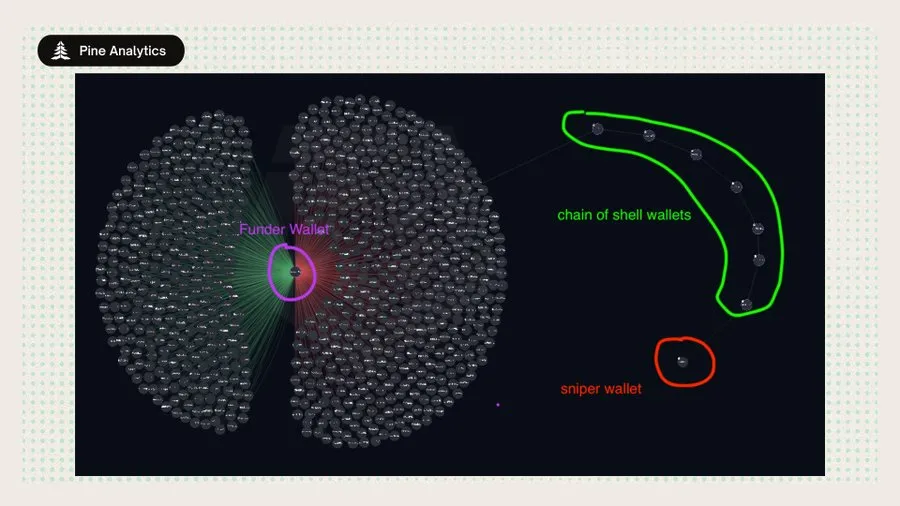

Case Study 2: Multi-hop Funding

The wallet GQZLghNrW9NjmJf8gy8iQ4xTJFW4ugqNpH3rJTdqY5kA was associated with multiple token sniping. This entity did not directly inject funds into the sniping wallet, but instead transferred SOL through 5-7 layers of transit wallets to the final sniping wallet, thus completing the sniping in the same block.

Our existing methods only detect some initial transfers by the deployer, but fail to capture the entire chain of the final sniper wallet. These relay wallets are usually "one-time use" and are only used to transfer SOL, making them difficult to associate through simple queries. This gap is not a design flaw, but a trade-off in computing resources - tracing multi-hop fund paths in large-scale data is feasible, but the cost is huge. Therefore, the current implementation prioritizes high-confidence, direct links to maintain clarity and reproducibility.

We used Arkham’s visualization tool to show this longer chain of funds, graphically showing how the funds flowed from the initial wallet to the shell wallet and finally to the deployer wallet. This highlights the complexity of the obfuscation of the source of funds and also points the way for future improvement of detection methods.

Why focus on “wallets that directly fund and sniped on the same block”

In the remainder of this article, we only study wallets that directly received funds from the deployer before going live and sniped in the same block. The reasons are as follows: they contribute significant profits; they have the least obfuscation methods; they represent the most operational malicious subset; and studying them provides the clearest heuristic framework for detecting and mitigating more advanced extraction strategies.

Discover

Focusing on the subset of “same-block sniping + direct funding chain”, we reveal a widespread, structured and highly profitable on-chain coordination behavior. The following data covers March 15 to date:

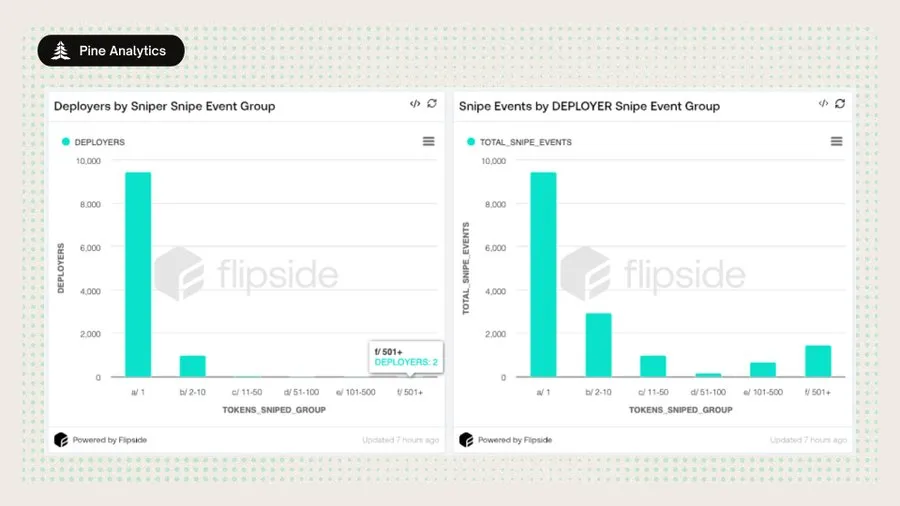

1. Sniping on the same block and funded by the deployer is very common and systematic

a. In the past month, it was confirmed that 15,000+ tokens were directly sniped by the funded wallets at the launch block;

b. Involving 4,600+ sniper wallets and 10,400+ deployers;

c. It accounts for approximately 1.75% of the total issuance of pump.fun.

2. The behavior is profitable on a large scale

a. Directly obtain funds from the sniper wallet and achieve a net profit > 15,000 SOL;

b. The sniping success rate is 87%, and there are very few failed transactions;

c. The typical income of a single wallet is 1-100 SOL, and a few exceed 500 SOL.

3. Repeated deployment and sniping to target farm networks

a. Many deployers use new wallets to batch create tens to hundreds of tokens;

b. Some sniping wallets perform hundreds of sniping in a day;

c. A “hub-and-spoke” structure is observed: one wallet funds multiple sniping wallets, all sniping the same token.

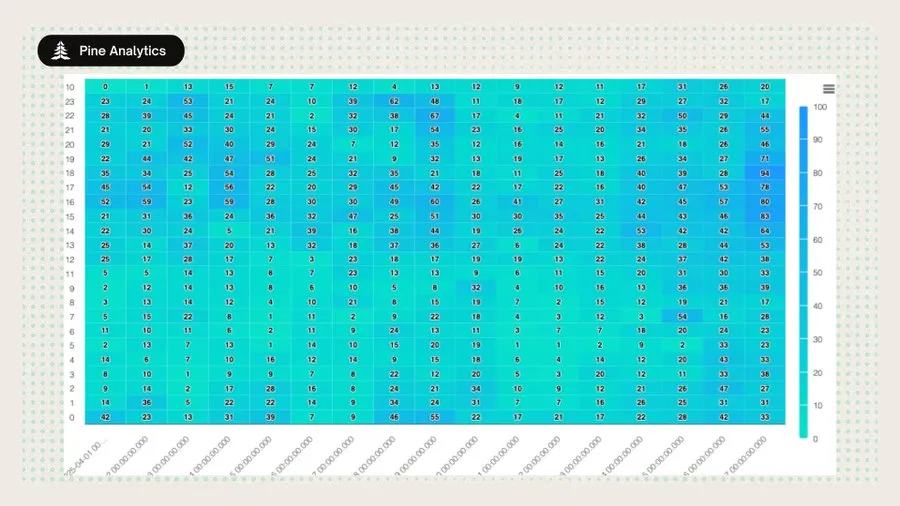

4. Sniping presents a human-centered time model

a. The peak activity is between UTC 14: 00 – 23: 00; it is almost stopped between UTC 00: 00 – 08: 00;

b. It matches the US working hours, which means it is manually/cron timed triggering, rather than fully automatic 24 hours a day around the world.

5. One-time wallets and multi-signature transactions confuse ownership

a. The deployer injects funds into several wallets at the same time and signs the same transaction to snipe;

b. These burned wallets will no longer sign any transactions;

c. The deployer splits the initial purchase into 2-4 wallets to disguise the real demand.

Exit Behavior

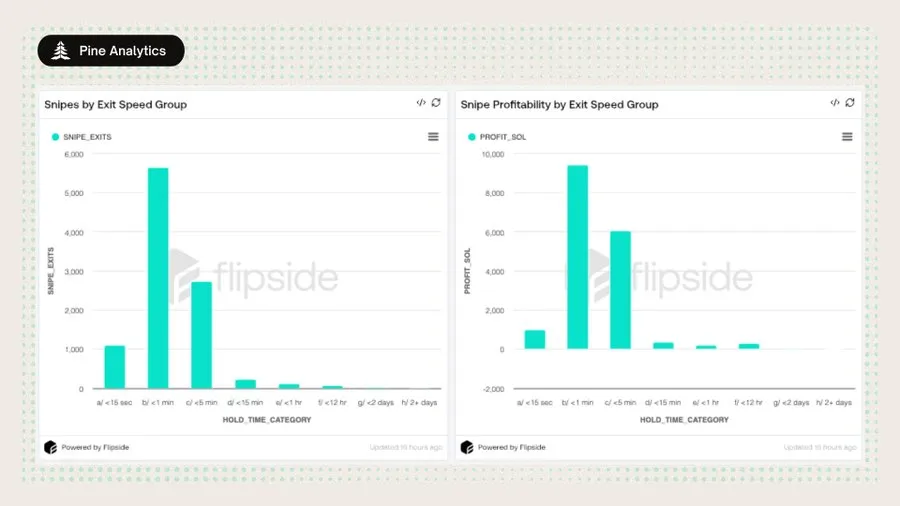

To gain a deeper understanding of how these wallets exit, we break down the data into two behavioral dimensions:

1. Exit Timing — the time from the first purchase to the final sale;

2. Swap Count — The number of separate sell transactions used to exit.

Data Conclusion

1. Exit speed

a. 55% of the snipers were sold out within 1 minute;

b. 85% of positions were cleared within 5 minutes;

c. 11% completed within 15 seconds.

2. Number of sales

a. More than 90% of sniper wallets exit with only 1-2 sell orders;

b. Gradual selling is rarely used.

3. Profitability Trend

a. The most profitable ones are wallets that withdraw money in < 1 minute, followed by wallets that withdraw money in < 5 minutes;

b. Although the average single profit from longer holding or multiple sales is slightly higher, the number is extremely small and the contribution to the total profit is limited.

explain

These patterns suggest that deployer-funded sniping is not a transactional activity, but rather an automated, low-risk extraction strategy:

· Buy first → sell quickly → exit completely.

Single sell means no concern for price fluctuations, just taking advantage of the opportunity to dump.

A few more complex exit strategies are the exception, not the mainstream.

Actionable insights

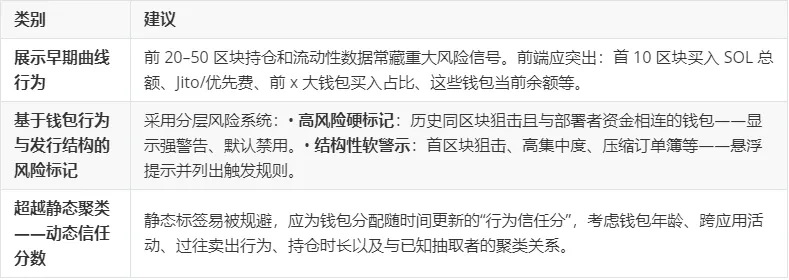

The following recommendations are intended to help protocol teams, front-end developers, and researchers identify and respond to extractive or collaborative token issuance patterns by transforming observed behaviors into heuristics, filters, and alerts to increase user transparency and reduce risk.

in conclusion

This report reveals a persistent, structured, and highly profitable Solana token issuance extraction strategy: deployer-funded same-block sniping. By tracking direct SOL transfers from deployers to sniping wallets, we pinpoint a group of insider-style behaviors that exploit Solana’s high-throughput architecture for coordinated extraction.

Although this method only captures a portion of the same-block sniping, its scale and pattern show that this is not scattered speculation, but an operator with a privileged position, a repeatable system and clear intentions. The importance of this strategy is reflected in:

1. Distorting early market signals to make a token appear more attractive or competitive;

2. Endangering retail investors — they become the exit liquidity without knowing it;

3. Undermine trust in open token issuance, especially on platforms like pump.fun that pursue speed and ease of use.

Mitigating this problem requires more than just passive defenses, but better heuristics, early warning, protocol-level guardrails, and ongoing efforts to map and monitor collaborative behavior. Detection tools exist — the question is whether the ecosystem is willing to actually apply them.

This report takes the first step: providing a reliable, reproducible filter to target the most obvious coordinated behaviors. But this is just the beginning. The real challenge lies in detecting highly obfuscated, evolving strategies and building an on-chain culture that rewards transparency rather than extraction.