专访区块链之父:区块链是为NFT诞生的,而不是加密货币

Interview: Jason Bailey

Interviewee: Scott Stornetta and Stuart Haber

Translation: Luffy, Foresight News

When Scott Stornetta and Stuart Haber invented the blockchain, they were thinking of something similar to NFTs, not digital currency. Jason Bailey, the founder of the art and technology blog Artnome.com, had an in-depth discussion with Scott Stornetta and Stuart Haber to explore the vision of blockchain in its early years and its subsequent evolution.

Translator's note: Scott Stornetta and Stuart Haber implemented the blockchain architecture in code in 1991, and it has been in commercial use since January 1995.

Jason Bailey: I often introduce you both as my good friends who "invented the blockchain." And then, I usually see a look of disbelief, "No, Satoshi Nakamoto invented the blockchain," even from those who have been studying Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies for years. Can you help people better understand your contributions and how these contributions formed the foundation for Satoshi Nakamoto to build the Bitcoin network?

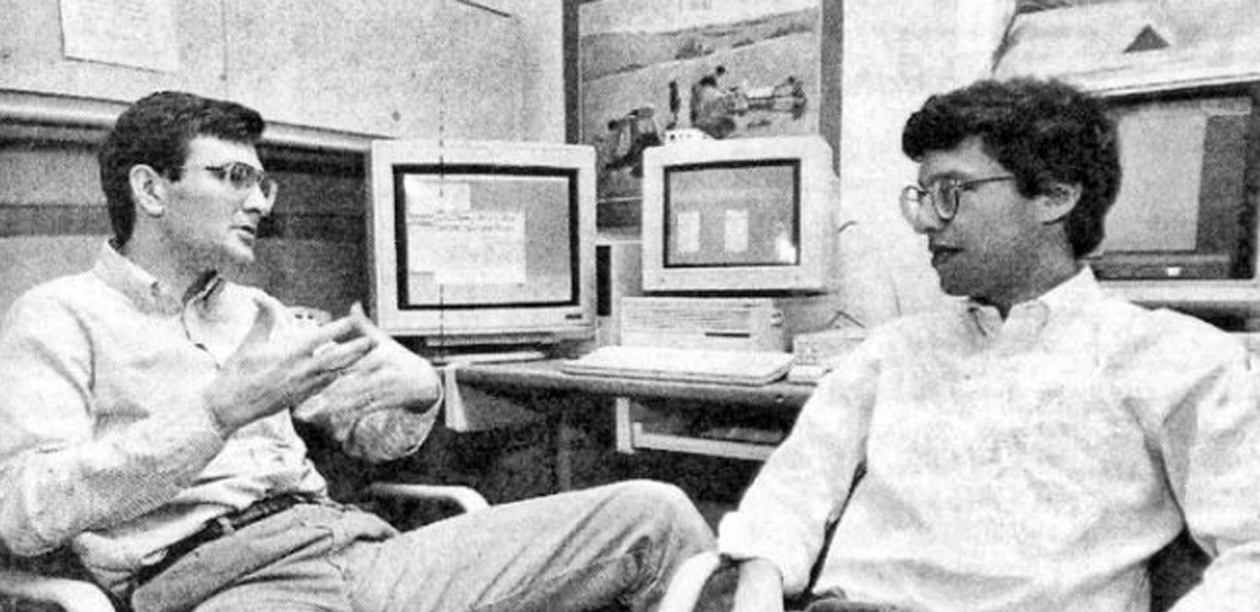

Stuart Haber: Well, let me tell the story by looking back at the history of about thirty years. From my perspective, that marked the beginning of the blockchain. It all happened in 1989 when Scott Stornetta and I were young scientists at Bellcore.

I was a cryptographer, and Scott had just joined Bellcore. He wanted to find a solution to ensure the integrity of digital records could be proven, guaranteed, and maintained through some program or algorithm. Scott strongly suspected that cryptography would play a role in it. So, we wrote a few papers and created an architecture together with Dave Bayer to solve this problem.

Scott Stornetta: Stuart and I formed a unique collaborative style characterized by a dynamic interplay of opposing viewpoints and constant exchange of ideas. I tend to immerse myself in thinking about such problems. The challenge was that I was not familiar with the foundational mathematics or cryptography that could be used to solve this problem. I had a question, but I didn't know how to find the solution. This knowledge gap has always been the driving force behind our productive collaboration.

SH: For those familiar with these concepts, digital signatures and cryptographic hash functions were proposed, implemented, and well understood as early as the fall of 1989. These tools offered a relatively simple solution to the problem of ensuring the integrity of records within a specific domain, requiring a trusted entity (whether it be an individual, software, or hardware) to ensure this. For many, this solution was considered satisfactory. However, Scott and I were not satisfied with this because we sought a solution that didn't require trusting any party and minimized trust in individuals, entities, and mathematical assumptions.

We ultimately developed a solution, explained it with a metaphor: "digital fingerprint". In fact, every blockchain project worldwide relies on cryptographic hash functions, mathematical algorithms with input and output processes that efficiently generate digital fingerprints of files. When you apply this process multiple times to the same file, you always get the same fingerprint output. It's an efficient process, even for large files, especially when we forget to close it and let it run continuously.

Now, another important property of cryptographic hash functions is that when you take two different files and calculate their fingerprints, you get two different results. Even if you make a minor change to the file, such as changing 0 to 1, the resulting fingerprints of these two different files will change significantly and unpredictably. For example, when it comes to financial records, even slight changes can have a profound impact on the meaning of the file. Changing the leading digit from 0 to 1 may be more advantageous for one party than another. Hence, the metaphor of fingerprint recognition is appropriate here: two different fingers have two different fingerprints.

Another important property of fingerprints is that they don't reveal detailed information about me. You cannot discern my height, hair color, or even if I have more than one finger from my fingerprint. Similarly, the fingerprint in a cryptographic hash function is just a sequence of numbers and letters, which doesn't reveal any information about the original file. However, if you have a fingerprint and claim to have a file that matches that fingerprint, you can easily verify its authenticity by "retrieving its fingerprint" again. This ability of digital fingerprint recognition is called cryptographic hash function, and these concepts were already established at that time.

JB: Allow me to summarize to ensure my understanding is correct. Hash or fingerprint is a well-understood concept. Your team's goal is to prove the integrity of records and make them tamper-proof. Are these hash values or fingerprints similar to blocks in a blockchain to some extent? Have you found a way to link these fingerprints into a blockchain?

SS: You're right. As Stuart mentioned, we realized that hash values can represent files more concisely and efficiently. The key innovation is combining them together (and constructing each block as a Merkle tree), then linking these blocks together, all using the same hash function. With Dave Bayer's involvement, we were able to link groups of records in such a way that each participant and their documents became holders of the record proof, acting as early nodes. This means that all the records are uniquely connected and widely distributed, containing many fundamental elements that Satoshi Nakamoto later used to create Bitcoin. We're not taking anything away from Nakamoto and his creation, but we see Bitcoin as an application built on top of the early blockchain. It's worth noting that Nakamoto explicitly references all publications related to the foundational work we were involved in. Our work is cited three times in the Bitcoin whitepaper, which references a total of eight external sources, of which we account for 3/8.

JB: So, how can we help bridge the gap between your work in the late 80s and early 90s and today's Bitcoin for all cryptocurrency enthusiasts who consider Nakamoto as the founder of blockchain?

SH: When you mention your contributions to blockchain to a general audience, they usually immediately associate it with Bitcoin or cryptocurrencies in a broader sense.

Scott and I weren't trying to invent cryptocurrency. In fact, the cryptographic community had already started working on creating purely digital currencies back in the 80s. Our focus was broader: we were truly concerned about the integrity of all records (including electronic records).

SS: This includes financial records, but our scope extends to every important record ever created, believing that all these records can be registered on the blockchain.

SH: Since it's impossible to predict which records will become significant in the years to come, why not include every record ever created?

JB: Essentially, you align more with the concept of NFTs rather than cryptocurrencies, right? When we see NFTs as tools for verifying art, contracts, patents, and various applications, it seems to align with your initial goals.

SH: Exactly. When discussing algorithm methods for digital records, we used the term "provenance." We focused on various types of records. However, when Satoshi Nakamoto aimed to establish a digital currency system and needed a method to ensure the integrity of financial transactions within the system, he directly adopted our solution. The data structure of Bitcoin transactions precisely reflects the data structure of our timestamp system, which was implemented in experimental code starting from October 1991 and put into commercial use in January 1995.

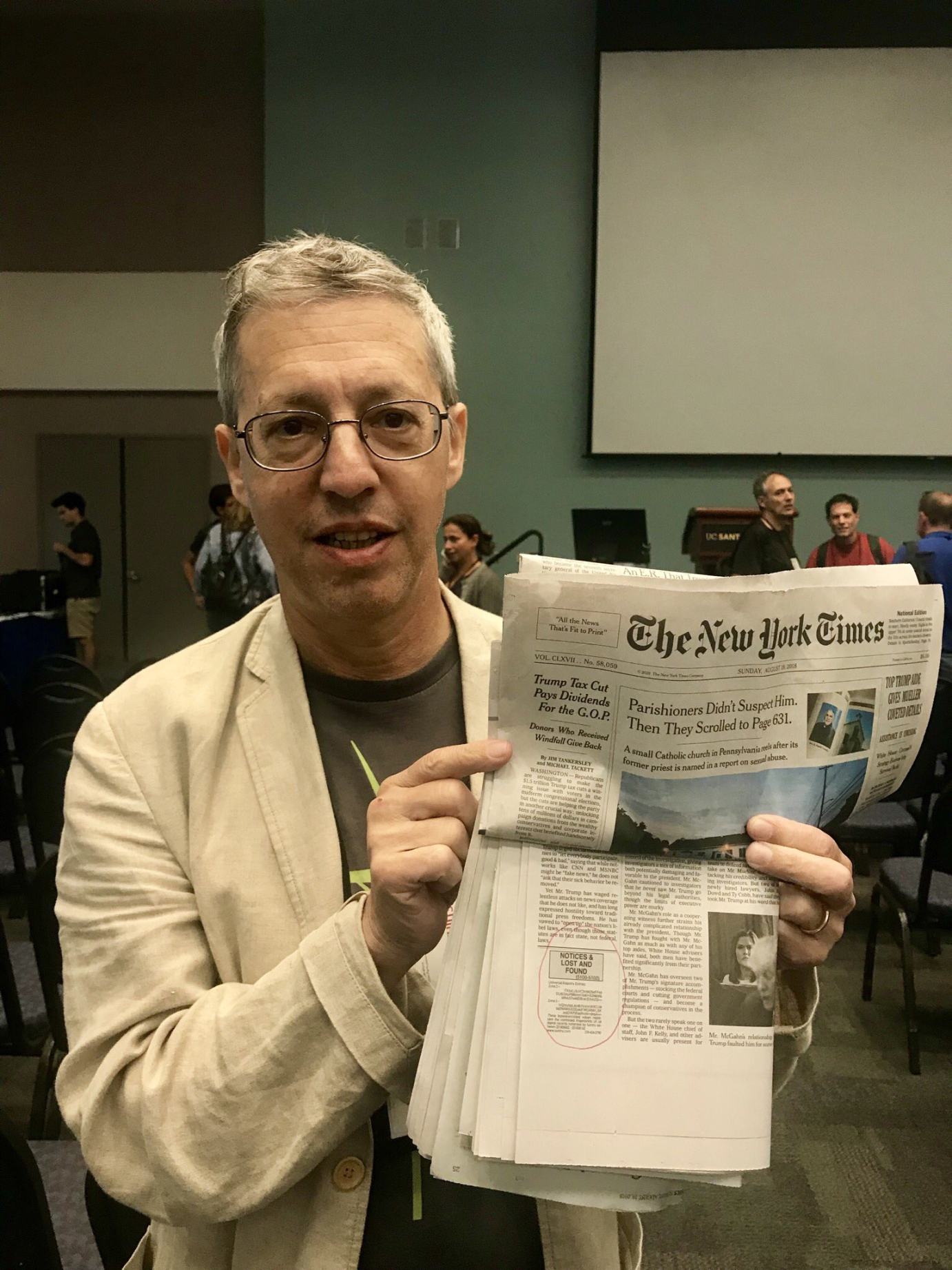

The longest-running blockchain started in 1995 and is still in operation. The timestamp is highlighted in red.

SS: I want to reiterate Stuart's point. Essentially, our vision of blockchain differs from Satoshi Nakamoto's. Nakamoto introduced an innovation in the field of currency but needed a robust record system. He seamlessly integrated that layer and built Bitcoin on top of it.

I want to emphasize that we don't overlook Nakamoto's contributions. On the contrary, he built Bitcoin on a blockchain formed by widely distributed Merkel trees, openly acknowledging that the concept had already been invented. Then, he directly created the mining mechanism using the same cryptographic hash function or digital fingerprint.

An interesting aspect is the recent popularity of ordinal plaintext in Bitcoin. If people delve into the footnotes of the Bitcoin whitepaper, they'll find that in our third joint paper, we hinted at the concept of leveraging blockchain plaintext or ordinals to create unique and non-fungible records. This concept is analogous to today's NFTs.

Your observation about cryptocurrency and NFTs is spot-on. To some extent, we consider NFTs as a more significant long-term realization of our initial goals.

It suggests that everything of importance, not limited to various cartoon primate postures, might eventually need unique registration as an NFT on the blockchain. Perhaps we should delve into our latest NFT series?

JB: I'm eager to hear more, especially now that we've clarified your contributions and their continuity with Nakamoto's subsequent creation of Bitcoin. It's fascinating that the blockchain you invented was more geared towards NFTs rather than cryptocurrencies, which might surprise some people. How did you decide to collaborate with artists and use illustrated news as the art for your NFTs?

SS: The early main challenge was to achieve universal consensus, which became more difficult due to the lack of the World Wide Web or similar technology. Our solution was to regularly create snapshots (fingerprints) of the blockchain and widely distribute them to prevent manipulation.

To achieve this goal, we chose to publish these snapshots weekly in the national edition of The New York Times. This version is preserved in libraries and archives around the world. Imagine the immense effort required to tamper with a single element in the tampering chain, like infiltrating every library in the world and altering their copies of The New York Times.

This is consistent with our approach to NFT collections. We released the initial 12 NFTs, with each representing one edition from our consecutive 12 weeks of publication in The New York Times. We collaborated with an artist to curate weekly events, selecting something whimsical, historical, or noteworthy and illustrating it.

Additionally, our plan includes releasing subsequent collections on various chains and protocols to foster greater collaboration and unity within the blockchain community. We have received inquiries from different blockchains and artists interested in preserving a set of 12 consecutive blocks. Our intention is not to centralize everything on widely-used blockchains like Ethereum. Instead, we aim to demonstrate that every community can have a piece of blockchain history.

Our goal is to gradually encourage greater interoperability and collaboration. Our goal is to provide an opportunity for artists, including graphic artists, to interpret the 12 value-related histories published in The New York Times during these weeks. This initiative aims to invite creative artists and blockchain founders to join us in commemorating blockchain history, rather than merely promoting NFT sales.

JB: That's fascinating! I think some people might be confused when they hear about you using The New York Times for the blockchain because they typically associate blockchain with computer technology, not traditional media like newspaper advertisements. However, the newspaper serves as a means to widely distribute in a tamper-proof manner, where no individual can maliciously alter it without penetrating every library globally...

SH: You can mess up our ad copy in The New York Times by scribbling or doodling on it. But the key is, if there's an issue, you can find your own record copy and validate it against others' records. This plan was originally Bellcore's experimental code that eventually developed into a company called Surety, whose main focus is protecting clients' digital records.

JB: Has your personality or political leaning influenced the invention of the blockchain?

SS: Yes. We don't need any annoying central authority to decide what's true or not. We once humorously claimed that our system is inherently distributed and even if the mafia is overseeing it, it's still a trusted system. However, we quickly realized that this description was inappropriate since we're based in New Jersey, so we stopped using it.

Personally, I greatly appreciate the inherent decentralization of blockchain. While I acknowledge the presence of centralized power, especially in Bitcoin, the fundamental premise remains: every participant shares the responsibility of trust, making files trustworthy for everyone. I find this concept to be very important and believe it can serve as the foundation for many institutions with a similar spirit.

SH: In the current design of so-called blockchain, our idea is to ensure the integrity of records without the need to trust a central authority.

SH: It is worth noting that some blockchain maximalists claim that blockchain, particularly their own blockchain, will overthrow all forms of government and central entities. Personally, I believe this statement is overly simplistic and unrealistic. In terms of the transformative potential of blockchain, I may be more pessimistic than Scott. Under the influence of economic forces, seemingly decentralized systems (including Bitcoin and Ethereum) become centralized.

SS: Indeed, Stuart and I have had multiple discussions on this topic. Whether we agree or disagree is not important; what is important is to recognize that blockchain technology represents a turning point and a form of creative destruction, as described by Schumpeter. It introduces a healthy tension between the desire for decentralization for trustworthiness and the need for operational efficiency through centralization. This tension is more desirable than pure decentralization because it can achieve more balance and diversity.

JB: In the cryptocurrency community, people often exhibit strong extremism towards specific blockchains, almost to a religious degree. However, it's clear that you support a future with multiple chains. Can you share more about your views on this?

SH: Certainly. One aspect we haven't discussed is our choice to launch an original series composed of dozens of NFTs on the Kadena blockchain platform, which we appreciate for various reasons. However, as we expand our NFT products, we not only encourage but also require any other NFT products to have interoperability. Our goal is to facilitate interoperability between different blockchain networks, just as we have done ourselves.

SS: I believe that in the future, various blockchain networks can coexist and be differentiated based on factors like on-chain/off-chain functionality. This diversity of functionality is a positive indicator of a thriving ecosystem. Stuart and I, in our own way, aim to promote interoperability among these blockchain networks and foster community awareness. So, if you represent a blockchain network that wishes to express opinions and collaborate, please reach out to us. Perhaps the next NFT collection (with 12 weeks of blockchain history) can be released on your blockchain platform.