The Moat of the Web3 Token War

Original compilation: Block unicorn

Original compilation: Block unicorn

A year ago, we talked about Aggregation Theory in the Web3 era. In the Web 2.0 era, aggregation platforms benefit from breaking distribution costs, bringing together many service providers. Platforms like Amazon, Uber, or TikTok benefit from hundreds of suppliers (suppliers, creators, or drivers) serving users. For users, they can get endless choices. For creators, using these platforms can reach audiences at scale.

In Web3.0, aggregation platforms mainly rely on the reduction of verification and trust costs. If you use the correct contract address to trade USDC tokens on Uniswap, you don't need to worry about the tokens being fake. NFT trading platforms like Blur also don't need to spend resources verifying the authenticity of each NFT traded on the platform, the network bears these costs.

In Web3, aggregation platforms can more easily check asset prices or find out where they are listed by examining on-chain data. Over the past year, most aggregation platforms have focused on aggregating on-chain datasets and making them available to users. This data may involve prices, yields, NFTs, or paths to bridged assets.

The assumption at the time was that companies that scaled fast enough to interface with the aggregator would establish a monopoly. I specifically cite Nansen, Gem, and Zerion (wallet aggregators) at the time as examples. Ironically, in retrospect, my assumption was wrong, which is what I wanted to write about today.

weaponization of tokens

Don't get me wrong, Gem (the NFT trading platform) was acquired by OpenSea a few months later. Nansen raised $75 million and Zerion raised $12 million in October. So, if you look at them as investors, my assumption is correct. Each product is a leader in its own category, but the reason I'm writing this is that the relative monopoly I'm assuming they'll have doesn't exist yet. Instead, they all face the rise of competitors, a desirable feature in emerging industries.

So what happened in the years that followed? As I wrote about in "Royalty Wars", the relative monopoly of Gem and OpenSea has been called into question by the launch of Blur in the market. Likewise, Arkham Intelligence combined an exciting user interface, a possible token launch, and clever marketing strategies, including referral reward tokens, to challenge Nansen. Zerion may be comfortable, but Uniswap's new wallet launch could erode their market share.

Are you seeing a trend? Aggregators that historically had no tokens and grew easily on the back of equity backers are now at risk as companies offer tokens to users. As the bear market deepens, the concept of "community ownership" will become very important, as the limited number of consumers who are still here will want to maximize every dollar they spend. Also, getting rewarded for using the platform rather than paying to access it is a novel experience.

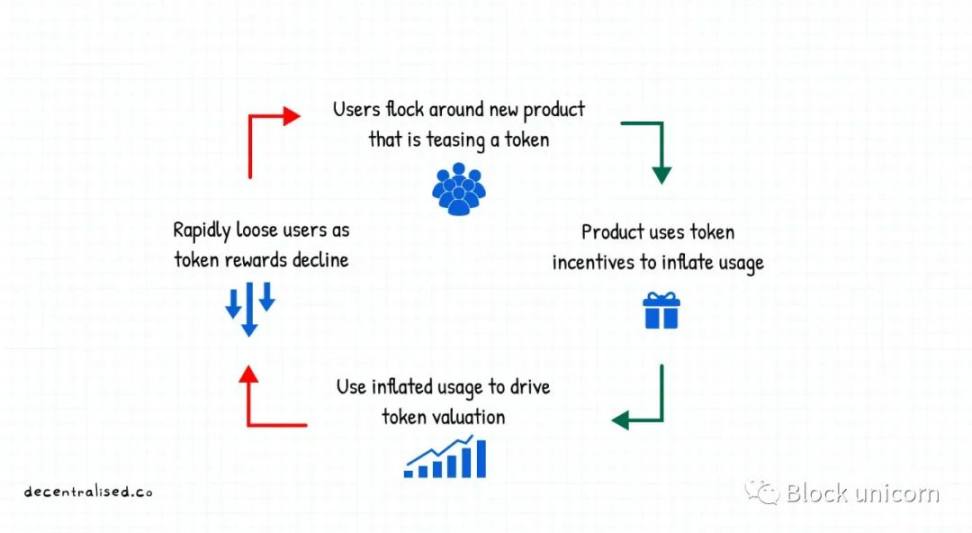

So, on the one hand, companies that have had good cash flows for a long time will see revenues decline, and on the other hand, they will see users flock to competitors. Is this sustainable? Definitely not sustainable, but it's a great example, and here's how it works:

The company launches a compelling token offering, especially if that offering is combined with a referral program. Arkham Intelligence provides tokens for referring users to their platform. Considering the possibility of airdrops, more and more users will spend time on the product. This is kind of a point, not a bug.

It's an incredible way to stress test your product. Reduce the customer acquisition cost of the product and guide the network effect. The challenge is retaining users, who often move to other products once token rewards are no longer offered. As such, most developers of "bait" tokens have no idea how broad their user base is.

Here's a summary from the guy below, outlining the philosophical underpinnings for the average person in the cryptocurrency space today. Very deep and meaningful, symbolizing the power of self-interest that drives our world.

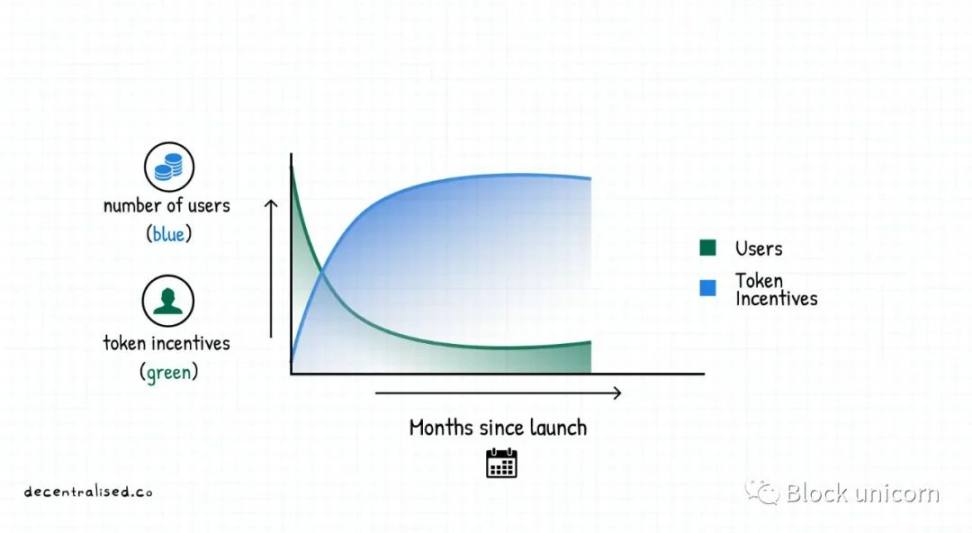

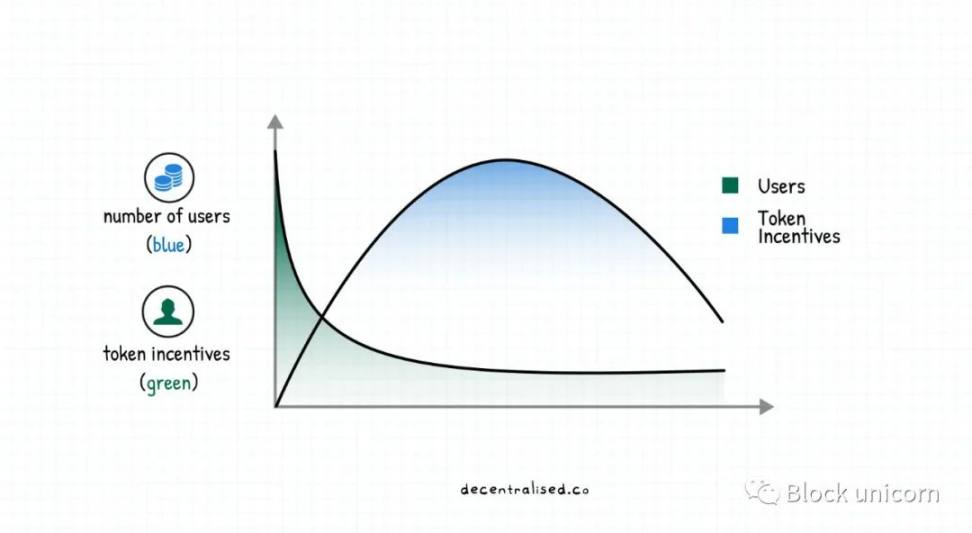

It is worth mentioning that in the past users have given up supporting projects with tokens in favor of existing giants. The trap is that the founders (probably) think that the users acquired through token incentives are sticky. Ideally, the relationship between token incentives and product users should look like the picture below.

But what actually happens is that users who initially flocked to a project almost completely abandon the project as token incentives dwindle. There is no reason why they can continue to attract users to contribute, a phenomenon that has plagued DeFi and P2P for the past two years.

Those users who have accumulated tokens and held them are new “community” members who want to know when the price of an asset can skyrocket, giving them an exit. (I point out that market participants are rational actors, driven by self-interest)

My original idea was to combine the functions of multiple products into a single interface, using the blockchain as the support of the infrastructure to form a long-term moat, but this idea is likely to be wrong. I have been wondering why in Web3, those relatively leading companies will lose their advantages, and other companies will take their place. Binance beat Coinbase, and they face competition from FTX. OpenSea has competition from Blur. Sky Mavis, maker of Axie Infinity, is likely to face pressure as new players enter the market such as Illuvium. Why do users in Web3 leave over time? How can we make users stay long enough?

What will be the moat in Web3 when everyone can publish a version with an embedded token? I've been thinking about this question a lot because we live in a market where narratives rotate. Each quarter has a new "hot" thing. That's why the venture capitalists I follow went from telecommuting experts to experts on Taiwan's geopolitical tensions overnight.

Of course, this certainly works if you are trading assets in and out (which IMHO is how most people are in crypto). But if you want to build an asset base that grows over time (like stakes in Google or Apple), frequent asset switching may not be a wise choice.

You ultimately want what you spend your time, money or energy on to grow without active management. And the only way to do that is for a product to do two things: first, and most importantly, retain the users they already have; How is this possible? (You know it's a bear market when one has to start thinking about moats and user retention)

Competition is for losers.

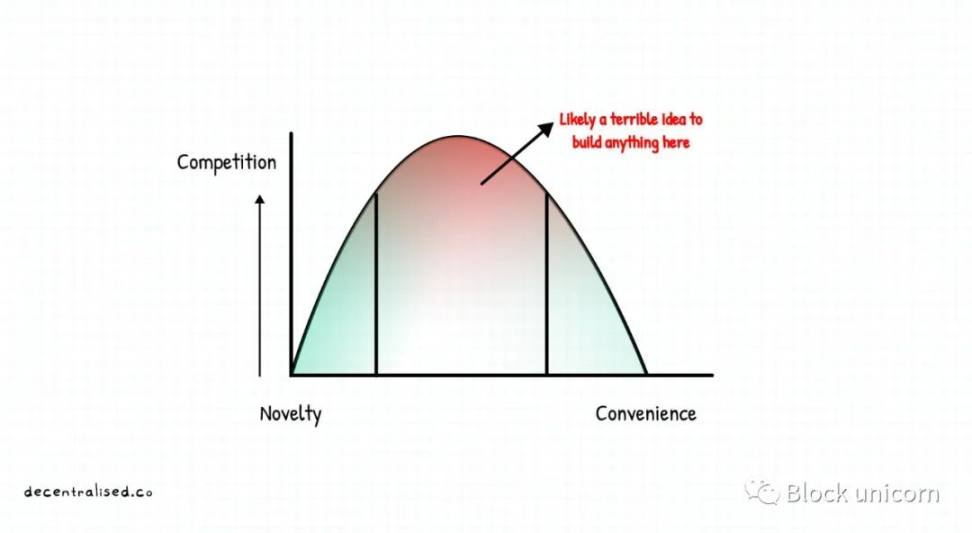

Part of what explains this phenomenon is ranking companies on a spectrum between novelty and convenience. In the early days, original products like NFTs were novelty, attracting people to go out of their way to try the product.

We are used to dealing with seed phrases/mnemonic and handling entry for wallets because the novelty of using "digital currency" is enough to pique our interest. Notice how patient users are by noticing the interest in Ordinals (Bitcoin’s ordinal NFT protocol).

Part of the reason for this patience comes from the early profit factor, speculation and profit make users willing to go through various ups and downs.

At the other end of the spectrum are highly convenient tools that we rely on every day. Amazon is an example of an aggregator that made us addicted to convenience. Consumers may benefit from not buying from niche stores on Amazon, and suppliers may be pricing them wrong on Amazon.

However, when making a decision, Amazon tells you that you don't need to consider payment methods, delivery times, or customer support. This "saved" mental effort translates into higher spending (attention or capital) on the aggregator.

Many sellers come to Amazon precisely because they understand that consumer behavior on the marketplace is different than that of consumers who shop directly in-store.

Tim Wu's 2018 article summarizes what people do for convenience:

Of course, we are willing to pay a premium for convenience, even more than we realize. For example, in the late 1990s, music distribution technologies like Napster made it free to get music online, and many people took advantage of this option. But while it's still easy to get music for free these days, no one really does it anymore. Why? Because the launch of the iTunes store in 2003 made it easier to buy music than to download it illegally, and convenience trumped free.

Going back to my original point, new technologies typically pay users to try them out. In contrast, high-convenience apps require users to pay high fees if they can satisfy users' desire for convenience.

The challenge with most consumer-facing apps today is that they lie in a middle ground, what I call the "valley of death." The products they created were not innovative enough, convenient enough to entice users to pay for their products, and not need to rely too much on them. Skiff, Coinbase Card, and Mirror (a decentralized creator platform) do well on the convenient side of this equation, as they can replace traditional comparable products.

But take topics like gaming, lending, or identity verification, and you can see why those topics haven’t scaled up on-chain yet.

Most apps in the middle make the fatal mistake of competing with each other. First, through advertising and recruitment, push up user acquisition costs and employment costs. Then, through toxic memes and encrypted narratives aimed at peers. As Peter Thiel said: Competition is for losers.

When startups start competing in small niche markets, there are generally no winners. In his words, the only way for startups to transition from the struggle for survival is to have monopoly profits, but how?

emergency moat

If companies in Web3 want to use tokens as levers for growth independently of tokens, they only have three levers to focus on: cost, use cases, distribution. This has happened in a few cases in the past, so let me break it down individually:

1. Cost

Stablecoins have become a killer use case for cryptocurrencies because they offer a better experience than traditional banking and are available globally. Innovations such as UPI in India may be more cost-effective for domestic payments, but transferring funds between South East Asia, Europe or Africa, or simply transferring balances between US bank accounts, makes more sense using on-chain transfers.

From the user's perspective, the costs incurred are not just the amount of money spent on the transfer, but also the time and effort required to move the funds. Debit cards have done for e-commerce what stablecoins have done for remittances: they reduce the cost of making transfers. By contrast, most consumer-facing revenue-generating mobile apps are different. While gains of up to two percent in dollars are possible, given the risk of collapse, its value proposition will fail.

2. Distribution

Distribution can be a moat if you gather some niche users in an emerging field. Consider how Compound and Aave have opened up a whole new lending market. Few people once thought that borrowing $50 of Ethereum with $100 pledged would bring much value. Some people are not served, mainly because these wealthy people do not want to sell their cryptocurrency in a bear market.

You would be wrong to think that people in emerging markets who do not have access to credit lines will drive the growth of DeFi lending volume. In fact, it’s the crypto rich, a previously underserved group, who use it. Being the "hub" for everything related to a niche allows you to focus on a single function, and Coingecko and Zerion are two businesses that do this very well.

Given that the marginal cost to a business of getting users to try a new feature is next to zero, it becomes cost-effective to add new revenue streams directly into the product itself. This is why businesses like WeChat (in Southeast Asia), Careem (in the Middle East) and PayTM (in India) tend to do well.

When players like Uniswap launch wallets, they are essentially trying to aggregate users on one interface in order to drive more features (such as their NFT marketplace) at a lower cost.

3. Use cases

Tools like ENS, Tornado Cash, and Skiff have carved out their own unique user bases. These users depend on the product in a way that traditional alternatives cannot provide today. For example, Facebook does not tie your wallet address to your identity. Your bank doesn't offer the same privacy protections as Tornado Cash.

The user stickiness of these products is very high, and there is no substitute that can compare with this product. First movers in new use cases will take a while to educate users and understand what the utility does, but they also have the advantage of capturing a significant share of the new market.

In the early days of LocalBitcoins, it was the only peer-to-peer trading place. This helped them amass liquidity for access to emerging markets such as India and kept them at the top until 2016. (RIP LocalBitcoins)

It is difficult for a bear market to gain scale by focusing on these levers. The examples I mentioned above have been through multiple market cycles. Part of the reason for Axie Infinity's rise is that the team has been building for two years before 2020. Before the next bull market arrives, the team has developed the "strength" needed to build the community, maintain the token, and balance the interests of investors (selling tokens) and users (earning tokens).

This explains why, from a VC perspective, investing in developer tools and infrastructure is popular, when the market is flagging. To counter the disinterest of retail investors, you want to focus on business-to-business matters. You build shovels for developers and let them attract retail investors themselves.

Well-known companies like Coinbase recognize this, which is why they release tools like wallet APIs during bear markets. We can see this phenomenon in terms of cross-chain bridges. I observed LI.FI closely and observed that the team is actively building an aggregated multi-chain basic ecosystem.

From Novelty to Convenience

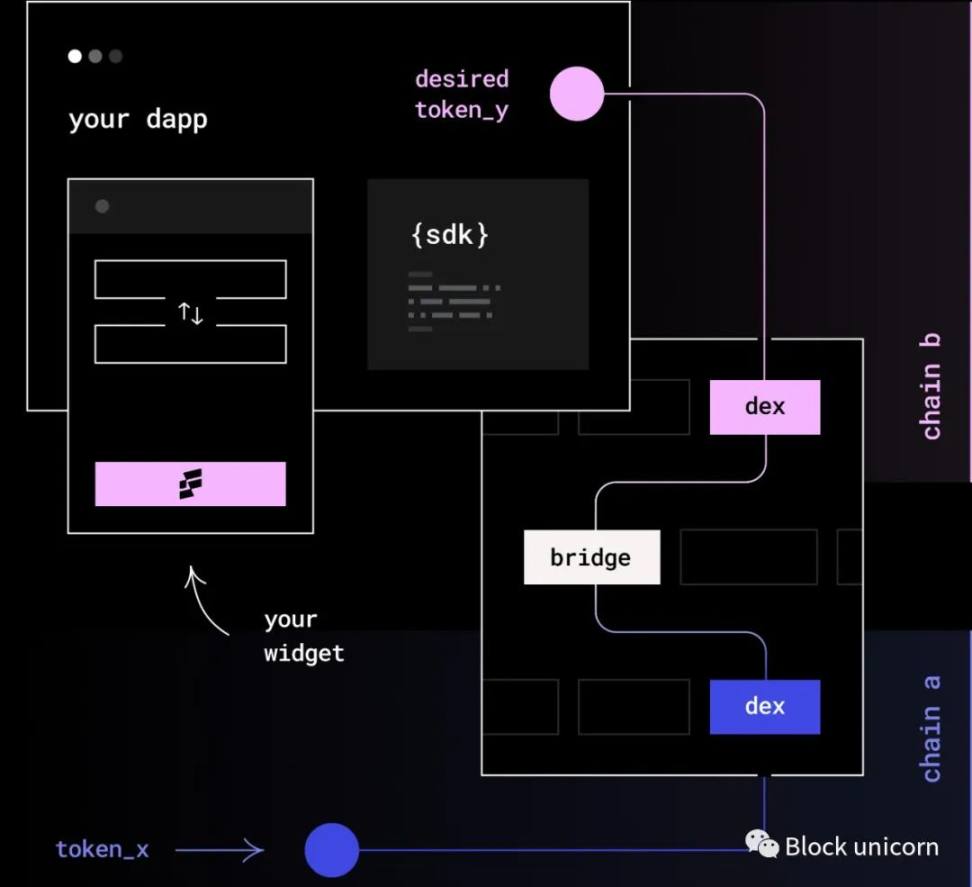

LI.FI is a homonym of "Liquid Finance", a multi-chain liquidity aggregator that provides an SDK for developers who want to make their applications or develop multi-chains.

Assuming that Metamask or OpenSea want to allow developers to easily allow users to transfer assets between chains, such as asset transfers between Polygon and Ethereum, LI.FI provides a simple SDK to determine the cross-chain bridge and DEX The best route to move funds so developers can focus on what they do best.

While there are several players in the same business, I'm using LI.FI as an example because they actually ticked off the aspects I mentioned earlier. (Also, Philipp originally shared with me how he sees the aggregator's eight months of development, which I've been basing this post on) But let's go back to LI.FI's strategy, they've been doing some Take the moat I mentioned earlier.

1. They focus on businesses from the start, not retail investors. If you catch the long tail of building applications that may require cross-chain transfers, you don't have to worry too much about attracting users directly.

2. Enterprises using this product can save research and maintenance time. In a bear market, you want to conserve resources as much as possible. So selling a product like LI.FI becomes relatively straightforward by default.

3. From an end-user perspective, an aggregator provides the best cost basis for transfers. Therefore, people want to use products that integrate their SDK.

4. They are often the first to integrate new blockchains - a frontier where competition is sparse.

5. Finally, their target group is mainly players who remain in the crypto industry. Generally speaking, in a bear market year, the people who speculate and trade in this industry are power users that you don't spend a lot of money to educate.

LI.FI is not the only cross-chain aggregator on the market, and while it fits the cost, crowd, and use case I mentioned earlier, it's hard to see how they can build their moat. However, I'm particularly interested in how they evolve from a novelty tool to a convenience tool.

In the earliest days, users relied on cross-chain aggregators because the process involved painfully waiting for transfers from exchanges. Instead of just a few clicks, you have to move funds through a centralized platform, go through a security check and hope it arrives.

So how to survive when the novelty wears off? You can see the answer if you pay attention to how Nansen and LI.FI operate, by looking at who they sell to. LI.FI is primarily sold to developers. Yesterday, Nansen launched a tool called Query to give corporates and large funds direct access to Nansen data. They claim the tool is 60 times faster than their closest competitor at querying data, so why are both companies focusing on developers?

It's about how a company can be both a novelty and a convenient tool if it sells to powerful users. For example, a developer decides whether to integrate with LI.FI - usually there is a simple calculation in their mind. Is the cost of an aggregator more effective in saving time and capital than integrating a single cross-chain bridge?

at last

at last

A year ago, I wrote about aggregators when I mistook a product feature (using blockchain) for a moat. Since then, DeFi yield aggregators have launched numerous products, most of which have failed. If competitors can launch products with the same features and better user experience, or introduce tokens like Gem's Blur, simply integrating the blockchain may not make much sense. In this environment, it is imperative to think about what can truly differentiate a product.

As I write these words, the pain of some patterns becomes apparent. First, the cost of acquiring users in a bear market will be very high because retail interest is low. Unless the product has a special novelty or convenience, it's in an odd position. Second, businesses building products for other companies (B2B) may be able to compound enough to survive and then dominate in a bull market, like FalconX (a cryptocurrency trading platform).

Third, if poorly designed, tokens are a temporary moat and a long-term liability, and few communities achieve meaningful appreciation of tokens for long enough.

When you think about retail-oriented niches like gaming or DeFi, it's clear that the average person doesn't care which chain to use or how decentralized something is, they care about the value they can get out of it, and blockchain can help Increase the value available to end users. However, founders often fall into the trap of building and selling for VCs (or token traders) without a moat built on top of cost, convenience, and community.