4D Discusses the Decentralization Road of Rollup Sorter

Original author:Jon Charbonneau

Original author:

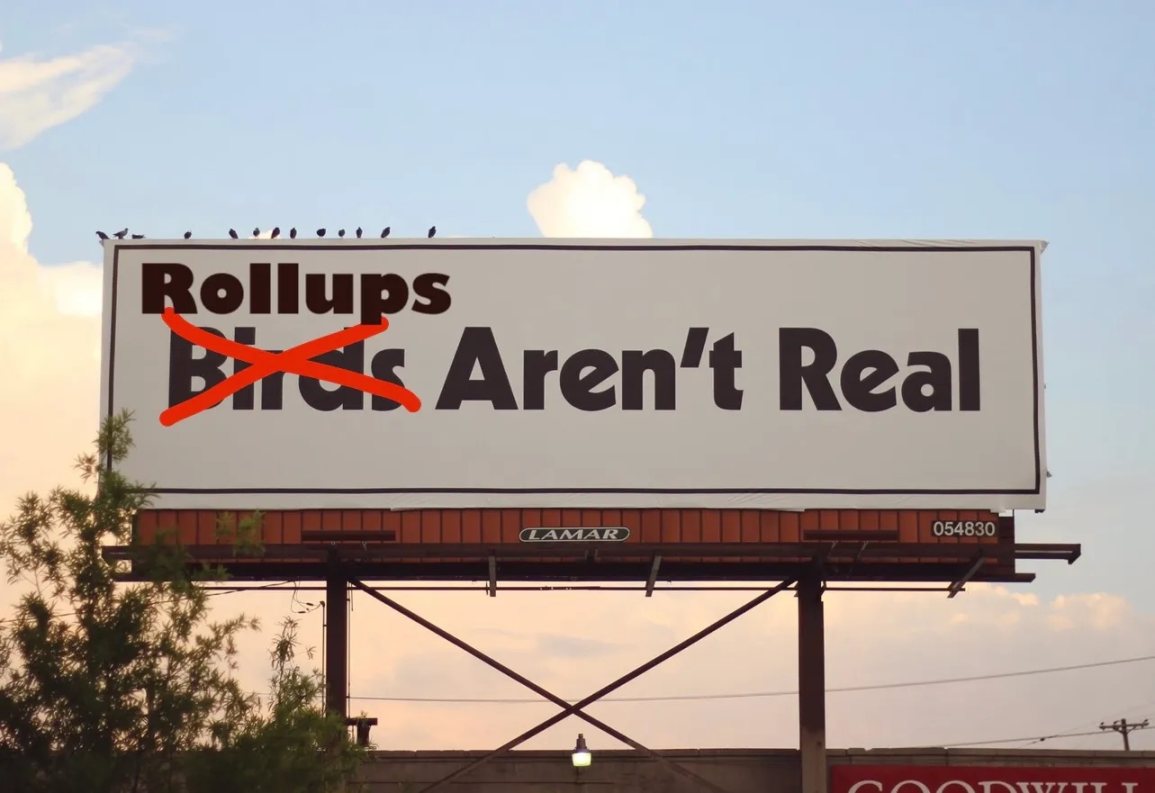

Original compilation: 0x11, Foresight NewsKelvin thinks "ZK Rollup" is not a real ZK Rollup, I think all "Rollup"Not a real Rollup

, at least not yet. So the question is, how do we make them true Rollups?

Most current Rollups require trust and permission:

Source: L2 Beat https://l 2b eat.com/scaling/risk

I will outline the situation in the following areas:

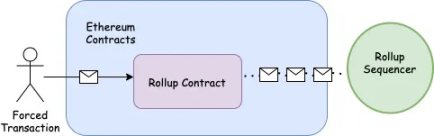

Forced Transaction Inclusion Mechanism: Even if a Rollup operator is censoring users, users should be able to force their transactions to be included to resist censorship.

L2 Sequencer Decentralization and (Optional) Consensus: Single Sequencer, PoA, PoS Leader Selection, PoS Consensus, MEV Auction, Rollup Based, Proof of Efficiency, etc.

Shared Sequencer & X-Chain Atomicity: This is really interesting new stuff.

MEV-Aware Design: I will briefly describe some variants of FCFS. Regarding the encrypted memory pool, you can refer to my recent article.

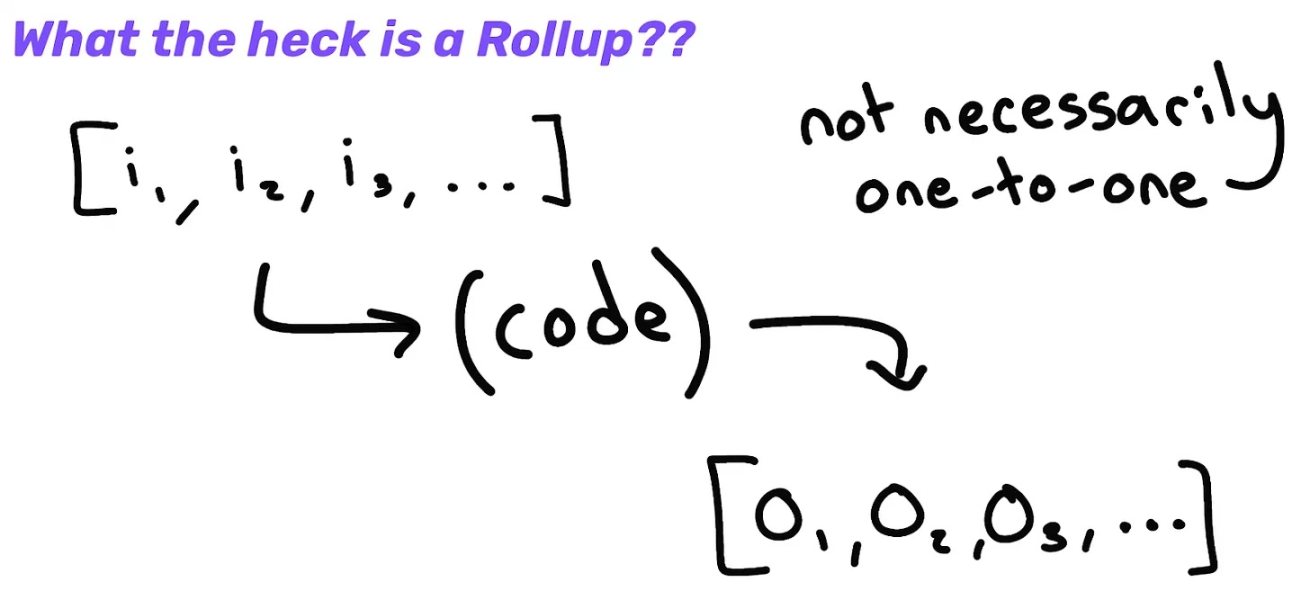

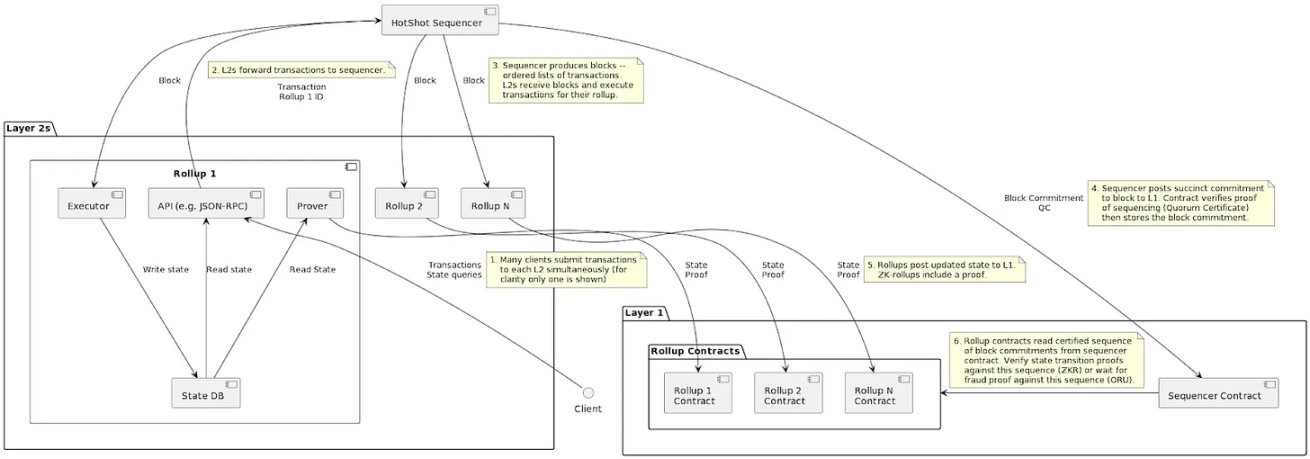

How do rollups work?

Smart Contract Rollup (SCR)

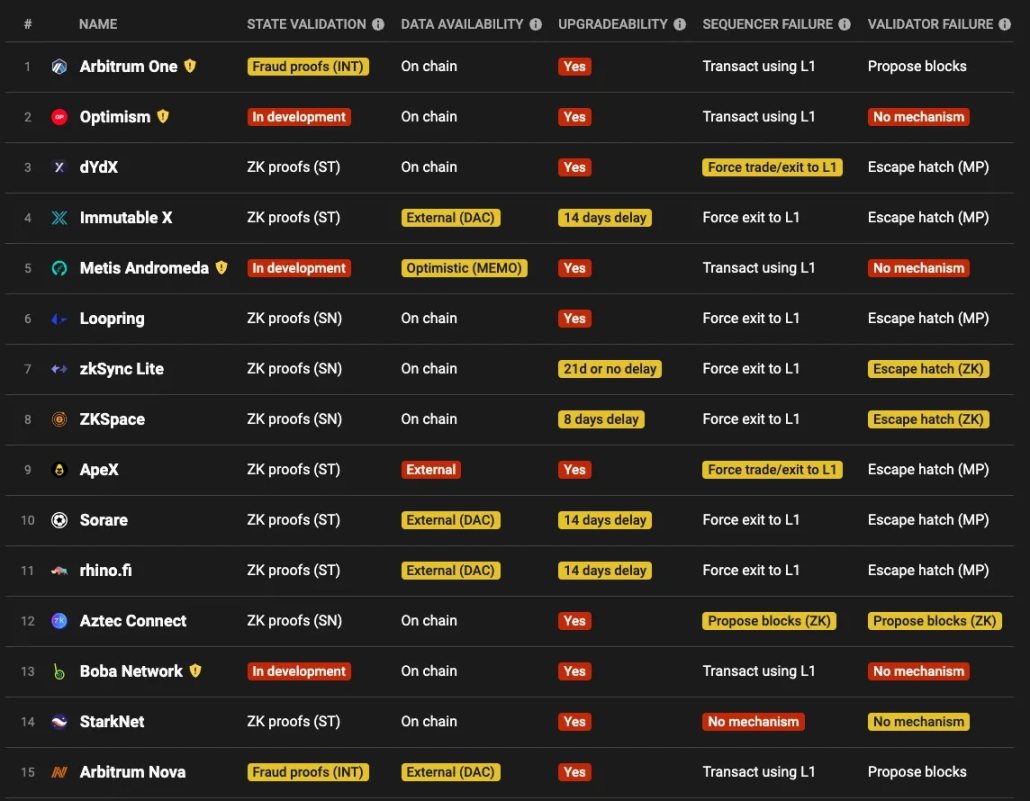

Smart Contract Rollup (SCR)First, a brief review of SCR'sworking principle

. The Rollups used on Ethereum today are all SCRs. At a high level, SCR is basically just:

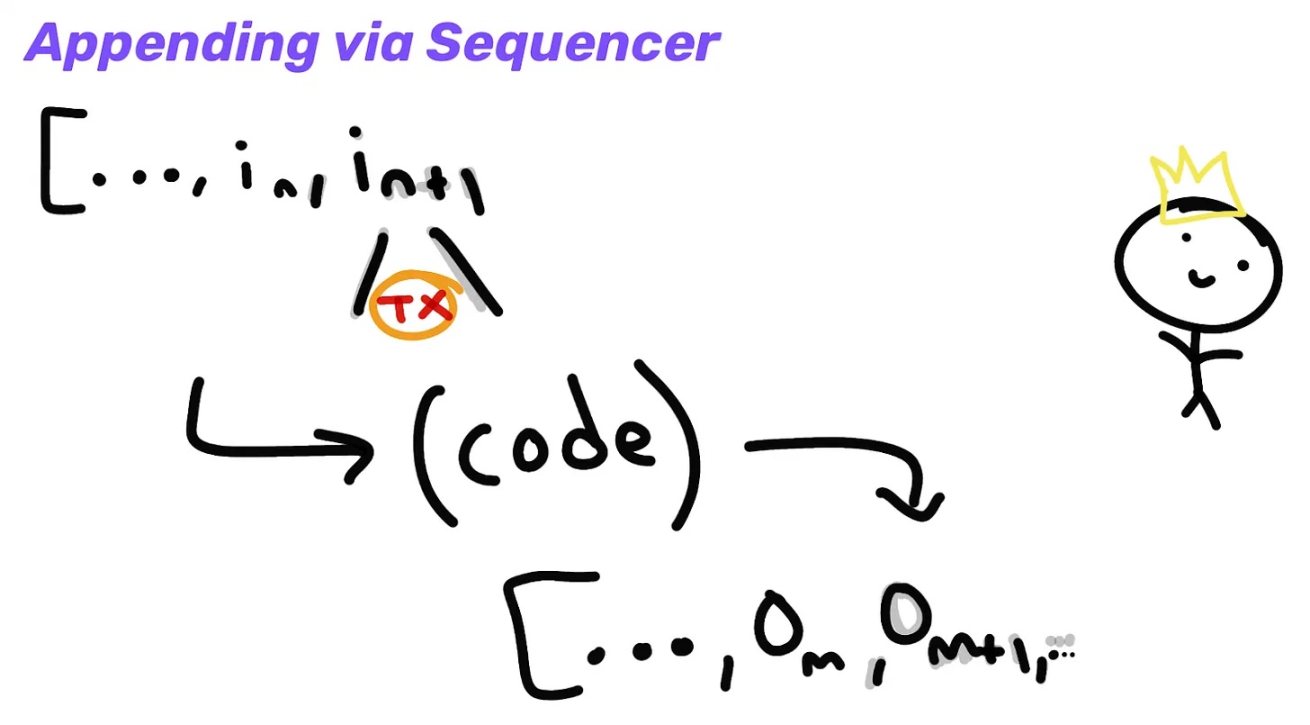

Ordered array of inputs (on L1, so transaction data must be published on the data availability layer)

Deterministic output based on input (Rollup blockchain)

image description

Source: How Rollups Actually Work - Kelvin Fichter https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKQz 9 jU 0 ftg

More specifically, traditional orderers submit Rollup blocks by publishing their state root and call data to their associated L1 smart contracts, and new blocks are added on top of the Rollup. The on-chain contract runs Rollup's light client, saving block header hashes. Contracts are confirmed settled upon receipt of proof of validity or after the end of the fraud proof window. If an unfinalized ORU block is invalid, it (and all subsequent blocks) can be orphaned by submitting a fraud proof of a rollback chain. Proven to help secure cross-chain bridges:

Transaction package submissions should require some type of security deposit to prevent malicious behavior. If a fraudulent transaction package is submitted (e.g. an invalid state root), the deposit will be burned and some will be distributed to the challenger who cheated the proof.SCR has "Merge Consensus

” — an on-chain verifiable consensus protocol. Rollup consensus can run entirely within L1 smart contracts. It does not affect the consensus mechanism of the main chain, nor does it require any support from the consensus mechanism of the main chain.

Decentralized consensus protocols generally consist of four main features (note that this is a simplification and does not clearly illustrate the full consensus protocol, e.g., leaderless):

Block validity function - state transition function. Block validity is enforced off-chain, via proof-of-validity or proof-of-fraud.

Fork choice rules - how to choose between two otherwise valid chains. Rollups are designed to achieve fork freedom by construction, so fork choice rules are not strictly required.

Leader selection algorithm - who is allowed to add new blocks to the blockchain.

Anti-Sybil attack - PoW, PoS, etc.

Given that 1 and 2 are still controversial, the minimum requirement for a decentralized orderer is some form of Sybil resistance + leader election. Fuel Labs has been working on this, and they argue that PoS:

Should not be applied to Rollups with a full consensus protocol (where validators/orderers will vote on blocks)

Should only be used for leader selection in Rollup

There are also good arguments why you should have an L2 local consensus, more on that later.

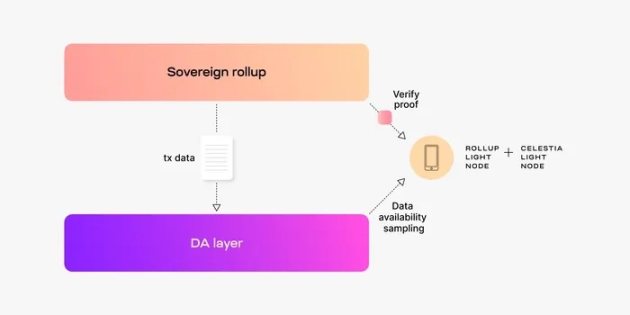

Sovereign Rollup (SR)

Sovereign Rollups still publish transaction data to L1 for data (DA) availability and consensus, but they handle client-side "settlement" in the Rollup. DA layers tell you the data exists, but they don't define the canonical chain for Rollup:

SR - There is no L1 smart contract that determines the "canonical" Rollup chain. Canonical Rollup chains can be determined by Rollup nodes themselves (check L1 DA, then verify fork selection rules locally).

image description

Source: CelestiaOn a related note: There is an interesting argument that there is no global canonical chain (only the bridge decides which chain is considered canonical). here is onecounterargument, others about Rollup's trade-offs before sovereignty and composabilitytwitter thread. I encourage you to sift through this information, as well as learn about recent。

herehere。

decentralized sorter

Forced transactions initiated by the user include

Smart contract Rollup

Smart contract Rollup

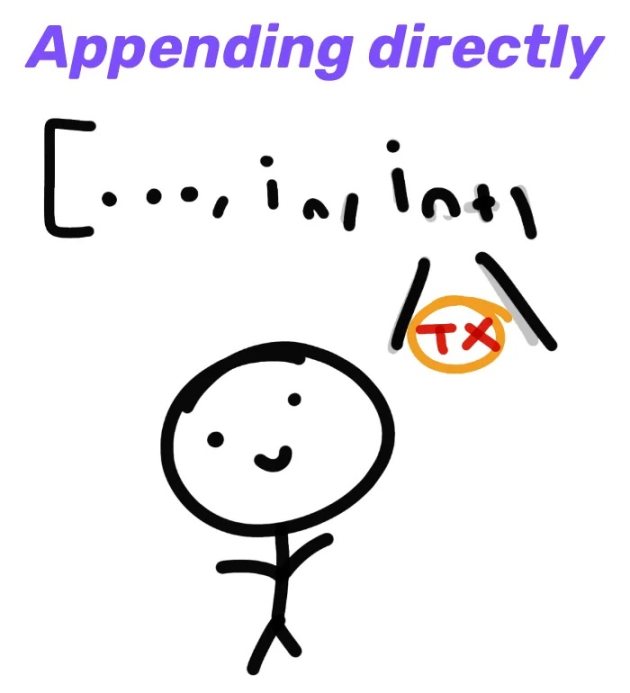

As mentioned above, the sequencer is generally responsible for batching transactions and publishing them to the L1 smart contract. However, users can also directly insert some transactions into the contract themselves:

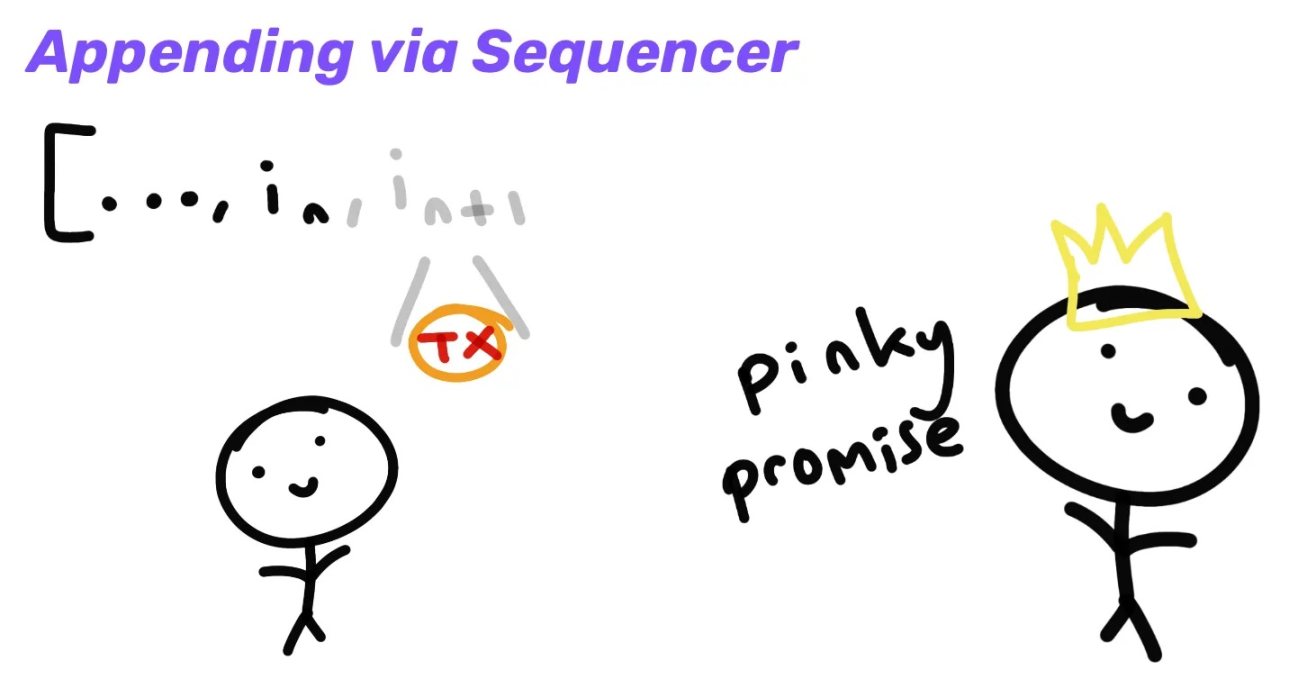

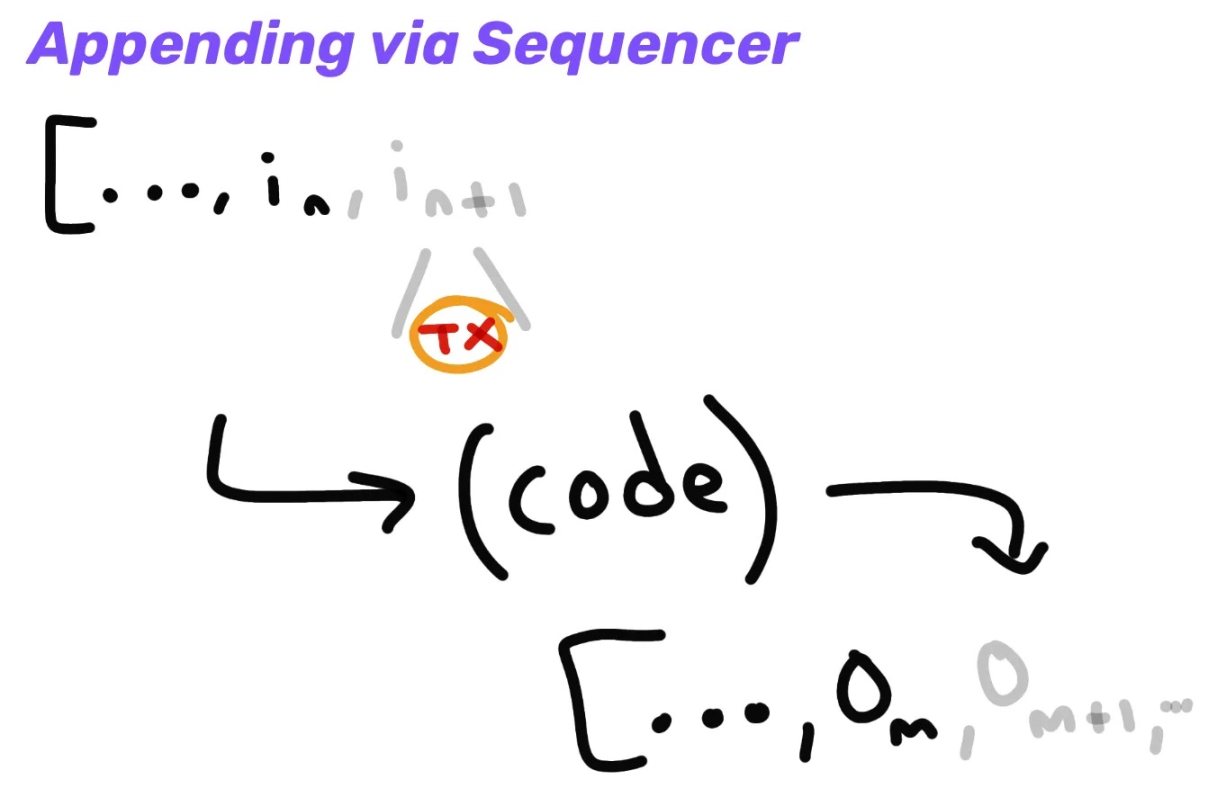

Of course this is inefficient and expensive, so the orderer will pack transactions and commit them together. This amortizes the fixed cost across many transactions and allows for better data compression:

The sequencer promises to eventually publish these transactions on L1, while we can compute the output for soft confirmation:

The output is further consolidated when the sequencer publishes these transactions to L1:

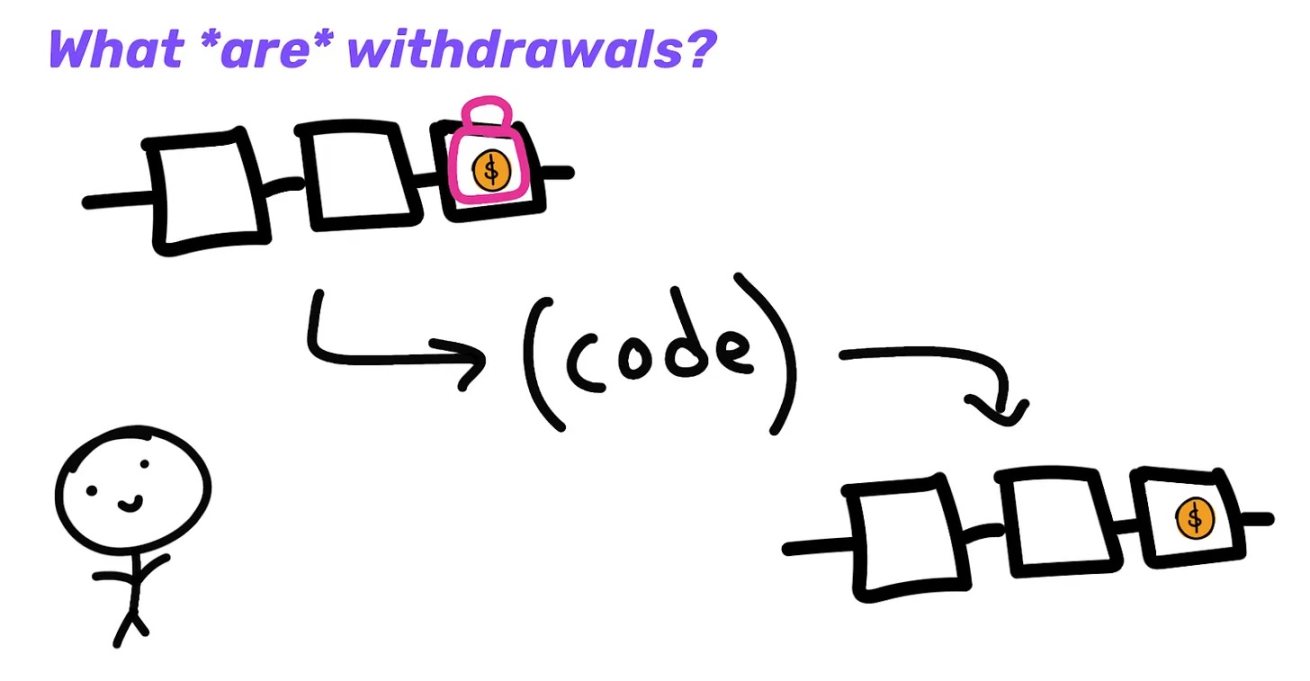

Typically, users will only include transactions themselves when bridging funds from L1 to L2. This serves as an input to the L1 contract, telling L2 that it can mint assets on L2 that are backed by assets locked on L1.

If I want to give my money back to L1, I can destroy it on L2 and tell L1 to give me my money back. L1 doesn't know what happened to L2, so it needs to submit a proof and a request to unlock my funds on L1.

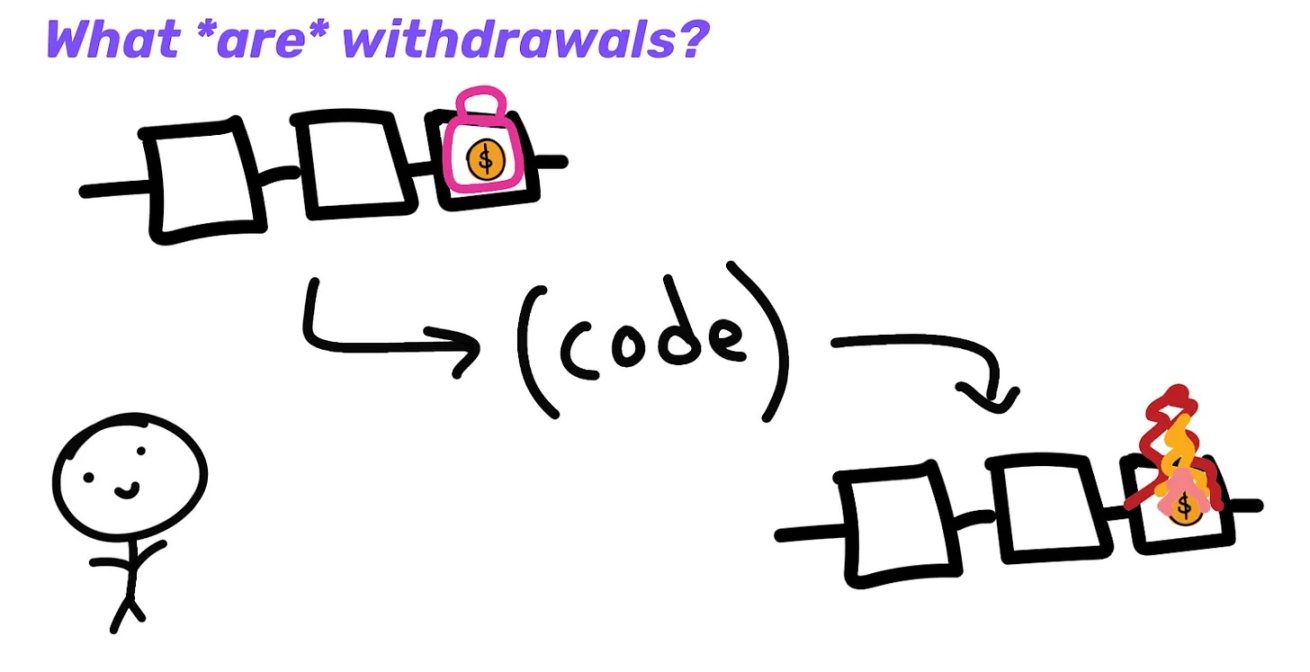

Because I came from L2, the sorter can initiate this withdrawal request and submit it to L1. However, now you trust the censorship resistance (CR) of the L2 sorter. You no longer have the same guarantees as on L1, maybe they don't like you, or the orderer shuts down and your assets stay on L2 forever.Rollup can add its own censorship resistance locally through various measures. This may include having an L2 consensus set with a high stake value,include list

Some variants of , adding threshold encryption, etc. to minimize the chance of L2 user censorship. These are all good practices, but ideally we also want L2 users to have the same censorship-resistant guarantees as L1.

If users are censored, they need some way to force exit Rollup or force their transactions into L2. This is why L2 users should retain the ability to, for example, force the direct inclusion of their L2 transactions into L1 contracts. For example, a censored user might be able to submit a single-operation transaction package directly to L1 itself.

Source: Starknet Escape Hatch ResearchThis is not ideal if the only option for L2 users is to force transactions directly to L1. This is not friendly to many low-value users, especially as interacting with L1 becomes increasingly expensive. A more advanced design might be able to work around this limitation by forcing atomic transactions between Rollups. Here Kalman Lajkó conducts a fascinating, which I highly recommend reading. It hopes to enable cross-Rollup forced transactions in systems with shared provers and DA layers.

Sovereign Rollup

wonderful post

In SCR, the L1 smart contract enforces Rollup's fork selection rules. In addition to validating the ZK proof, it also checks that the proof is built on top of previous proofs (as opposed to other forks), and that it processed all relevant mandatory transactions sent on L1.

SRs can publish their ZK proofs to the L1 DA layer for all to see as calldata/blobs (even if L1 doesn't validate them). Then, you just add a rule that new proofs are only valid if previously valid proofs are in place. This rule can be enforced on the client side, but it will require the user to scan the history of the chain.

The calldata can be bound back to the L1 block header, and a statement can be added saying "I have scanned the proofs of the DA layer (starting at block X and ending at block Y), and this proof builds on the most recent valid proof". This proves the fork choice rule directly in the proof, rather than enforcing it on the client side.

Since you are already scanning proofs, you can also prove that you have scanned any forced transactions. Anyone can post forced transactions directly to the L1 DA layer when needed.

Hierarchy of Transaction Finality and ZK Fast Finality

On-chain proof verification on Ethereum is usually very expensive, so current ZKRs (such as StarkEx) tend to release STARKs to Ethereum every few hours. Proofs tend to grow very slowly relative to the number of transactions, so this batching can provide significant cost savings. However, such a long finalization time is not an ideal user experience.

If Rollups only publish state differences on-chain (rather than full transaction data), then even full nodes cannot ensure finality without proofs. If Rollup's full transaction data is posted on-chain, then at least any full node can do it with L1.

Usually, light nodes will only rely on the centralized orderer for soft confirmation. However, ZKR can quickly generate and distribute ZK proofs in the p2p layer for all light clients to see in real time, while providing them with finality at L1 speed. Later, these proofs can be recursively packaged and published to L1.

This is what Sovereign Labs plans to do, and similarly, Scroll plans to publish intermediate ZK proofs on-chain (but not verify them), so light clients can sync up fairly quickly. In both ways, Rollup can start to complete finality at L1 speed instead of waiting to save gas costs. Note that in both cases you're only reducing the finalization time to the absolute minimum (L1 speed).

No sorter will ever achieve finality faster than L1. The best a different orderer design can do is give you preconfirmation faster than L1, with different levels of certainty (e.g. preconfirmation for L2 with a decentralized consensus set is faster than a single trusted orderer device is more reliable).Patrick McCorry also recently traded for Rolluplevel of finality

Gives a good overview.

There are different levels of transaction "finality" depending on who commits to you (and what the rollup structure is)

Different actors are aware of the "truth" differently at a given time (e.g. L2 light clients, full nodes and L1 smart contracts will be aware of the same "truth" at different times)

single sorter

Most current Rollups have a sequencer for submitting transaction bundles. It improves efficiency, but also brings less real-time liveness and censorship resistance. With the proper safeguards in place, this may be acceptable for many use cases:

Censorship Resistance: A mechanism for user-enforced inclusion of transactions, as described above.

Liveness: Some kind of hot backup option is available if the primary orderer fails (similarly providing a backup for ZKR provers, while ORU fraud provers should be permissionless). Anyone should be able to step in if the backup sequencer also fails.

For example, alternate orderers can be elected by the Rollup governance mechanism, and users gain security, censorship resistance, and liveness. Even in the long run, a single active sequencer is a viable option.

Base could be the start of a new trend. Companies can now manage and optimize their products as excited as they are about the enterprise blockchain bullshit, but it can actually be a permissionless, secure and interoperable chain now.

Base eventually intends to decentralize their set of sorters, but the point is that they don't strictly need to do this (or they can in very limited scope, e.g. small sorter sets). To be clear, this requires Rollup to implement the necessary steps to ensure it is actually secure and maintain censorship resistance (removing any instant upgrades, enforcing robustness proofs, enforcing transaction inclusion, MEV auctions, etc.).

This will be a huge improvement over centralized/custodial offerings, not a replacement for the largest decentralized offerings. Rollup simply expands the design space. This is also the main reason most Rollup teams don't make orderer decentralization a top priority - other projects place more emphasis on user security, censorship resistance, and less trust in Rollup operators.

However, this is still not ideal if user/other parties need to step in to stay alive and "real-time censorship resistant" (vs. "ultimately censorship resistant", e.g. forcing transactions through L1). Depending on the mandatory transaction inclusion mechanism, low-value user intervention may be costly or impractical. Rollups with a high preference for real-time censorship resistance and maximum guarantees of liveness will seek to decentralize. There may also be regulatory considerations when operating a single licensed sequencer.

Proof of Authority (PoA)

An immediate improvement over a single sorter is to allow a small number of geographically distributed sorters. Sorters can simply be rotated, and creating connections between them will help incentivize honest behavior.

This concept should not be too unfamiliar - multi-signature bridges usually have a small number of trusted companies, or similar committees, such as Arbitrum's AnyTrust DA. But importantly, they have much less power here (you don't rely on Rollup orderers for security, unlike how multi-signature cross-chain bridge operators withdraw locked funds). Overall, this scheme is better in censorship resistance and liveness than single-orderer, but still not perfect.

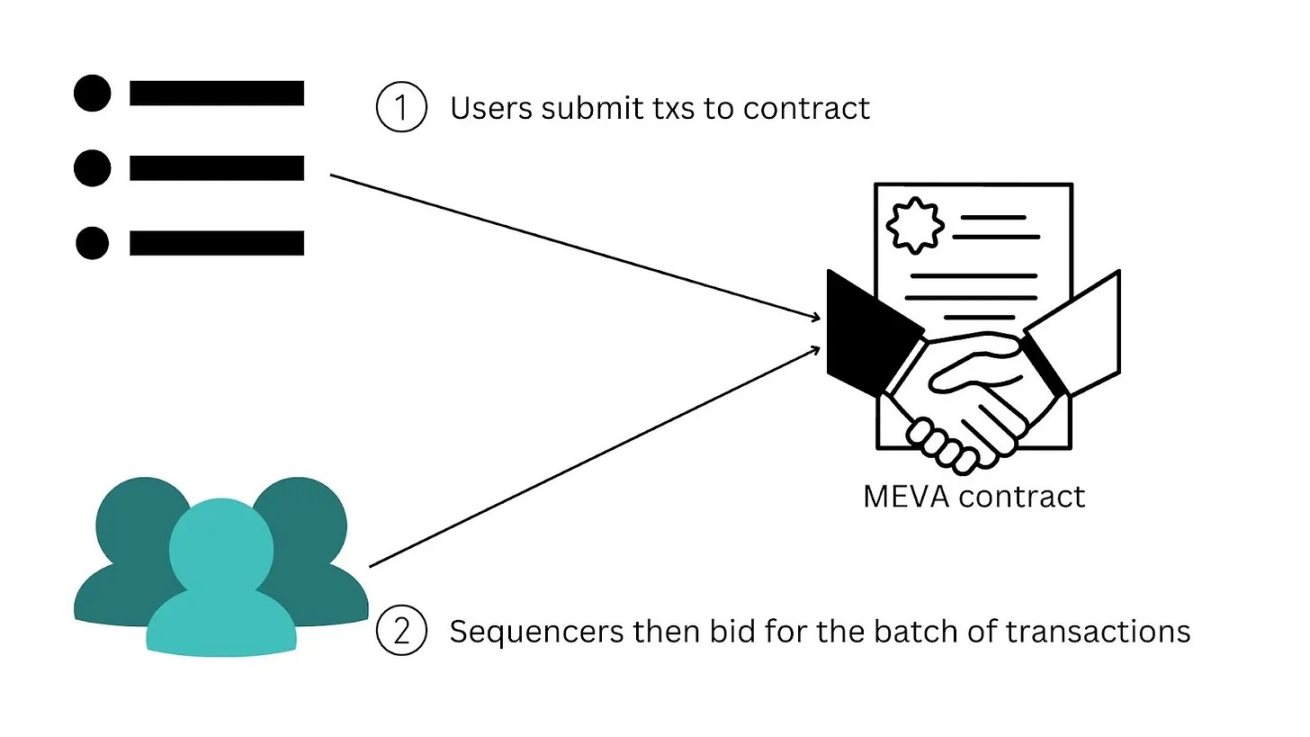

Sorter Auction aka MEV Auction (MEVA)

Rollup can also run MEV Auctions (MEVA) directly via smart contracts, rather than assigning ranker rights based on stake. Anyone can bid for the ordering rights of transactions, and the auction contract awards the ordering rights to the highest bidder. This can be done for each block, or for an extended period of time (e.g. bidding for the right to be the next day's orderer). Winning sequencers should still submit a bond that guarantees penalties if they subsequently malfunction or act maliciously.

Source: Decentralization of ZK Rollup

In practice, MEVA outside the protocol is the most natural outcome if the auction is not directly incorporated into the protocol. If sorting rights were determined based on stake weights, some form of MEV-Boost/PBS-style auction system would emerge, similar to what we see today on L1 Ethereum. In this case, fees/MEV may be distributed to stakers. If the auction is incorporated into the protocol, then the fees/MEV will likely go to some form of Rollup DAO treasury.

Permissionless PoS for leader election

You can join as a sequencer without permission, but you must stake tokens (probably L2's native token). The staking mechanism can be built on top of the base layer through smart contracts or directly in Rollup. You can use this PoS combined with some form of on-chain randomness for leader selection, much the same as any L1. Your probability of ordering a block = your fraction of the total stake. Penalties can be imposed on wrong/malicious sequencers through slashing etc.

Note that this does not require the orderers to reach consensus for the reasons above. Rollup uses L1 for consensus, so no local consensus is required. Staking determines which orderers can propose blocks, but they are not required to vote on blocks proposed by other orderers.

Dymension

Ordering rights can also be granted for any length of time. You might have access to sort 100 consecutive Rollup blocks, or 1000, etc. Longer cycles may be more efficient and require only one sequencer at a given time. However, granting an expanded monopoly may have other externalities.

Dymension is a project that puts these ideas into practice. Dymension Hub will be a typical honest majority PoS L1 in Cosmos. Its L2s ("RollApps") will use it for settlement and consensus, while relying on Celestia for DA (so those L2s are actually "Optimistic Chains", not "Rollups").Litepaperaccording to their

, Decentralized RollApp sorting will need to mortgage DYM (Dymension's native asset) on Dymension Hub. Leader selection then depends on the relative amount of DYM staked. These Sequencers will receive revenue (fees and other MEV) from their respective Rollups, and then pay the associated costs to Dymension Hub and Celestia.

As a result of this mechanism, almost all value capture in this stack is accumulated directly into DYM tokens. Rollups that sort using their own native token (as StarkNet intends to do with STRK) add value to their own token. This setting inspires a question: Can Ethereum Rollup only use ETH for sorter election?

In my opinion, this greatly reduces the incentive to deploy L2 on such a settlement layer. Most L2 teams naturally want their own tokens to generate meaningful value (rather than just being used for fees).

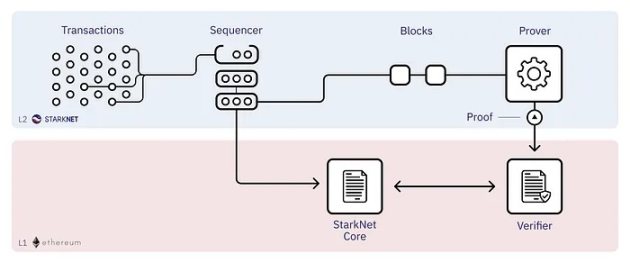

Permissionless PoS for leader election and L2 consensus

L2 staking can also be used for orderer election and local consensus if desired. This is exactly the token model of the StarkNet (STRK ) plan:

PoS Consensus: Incentivize L2 validators to reach temporary L2 consensus before L1 finalization, providing stronger pre-confirmation. It's not a strict requirement, but it's an attractive option.

Additionally, STRK can be used in some form to:

Additionally, STRK can be used in some form to:

Proof: Incentivize the prover to produce STARK.

The transaction process is as follows:

The transaction process is as follows:

Sorting: the sorter sorts transactions and commits a block

L2 Consensus: StarkNet Consensus Protocol Signs Proposed Blocks

Proof Production: The prover generates proofs for consensus-agreed blocks

L1 state update: Proof is submitted to L1 for state updateFor more details about the StarkNet program, you can refer to this article。

post

L2 consensus, or just L1 consensus?

L2 may or may not implement its own local consensus (ie, L2 validators sign their blocks before sending data to L1 for final consensus). For example, an L1 smart contract can learn from its rules that:

PoS for leader election and consensus: "I can only accept blocks signed by L2 consensus."

PoS for leader election: "This is the chosen orderer, and blocks are allowed to commit at this time."

Rollup If there is no local consensus, what you need to do is:

Make Rollup block proposals permissionless.

Create some criteria to choose the best block to build for a given height

Have nodes or settlement contracts enforce fork selection rules

Inherit consensus and finality from L1

Note that in either case, the value of L2 can be accumulated into Rollup tokens. Even though L2 tokens are only used for some form of leader selection (not consensus voting), the value of ordering power is still accrued to L2 tokens.

Drawbacks of L2 Consensus

Now let's discuss the tradeoffs of having/not having local consensus before L1.A proposed by the Fuel Labs teamargumentIt is believed that L2 consensus will reduce censorship resistance. “This allows a majority of validators to review new blocks, which means user funds can be frozen. No need for PoS to secure Rollups, as Rollups are secured by Ethereum.” This is a moot point. As mentioned earlier, even censorship orderers can still provide censorship resistance (for example, forcing transactions to go directly to L1, ormore complex designKalman Lajkó,For example

design under study).

Another way of saying this is that reaching full consensus is "inefficient". For example, the former case below seems easier:

One master sequencer runs everything at one time.

For a period of time, a master orderer runs everything, and then all other nodes need to vote and agree.

As stated, some have expressed concerns about using PoS in orderer decentralization. The complexity of L1 and L2 can make dealing with certain types of attacks more challenging.

Advantages of L2 Consensus

Probably the biggest goal of the sequencer is to provide users with faster soft confirmation before the full safety and security of L1. Check out the mechanics of StarkNet:

"Strong and fast L2 finality - StarkNet state only becomes final after a transaction packet is proven L1 (which can take hours). Therefore, L2 decentralized protocols should execute before the next transaction packet is proven order to make meaningful commitments.”Consensus backed by the economic security of multi-orderers helps provide:

stronger guarantee

“Starknet consensus must be accountable, as violations of safety and liveness are punished, as are any fraction of participants (including malicious majorities).”

Rollup also has the flexibility to experiment with different tradeoffs within the range of consensus mechanism options, as they can always eventually fall back to the safety and dynamic availability of Ethereum L1.

Rollups sorted in L1

The above Rollups all build specific sorters to create Rollup blocks in some form. For example, PoS can join without permission, but at a given slot, only elected L2 orderers can submit blocks. There are also related schemes that do not rely on any L2 sorter, they sort transactions through L1 itself.

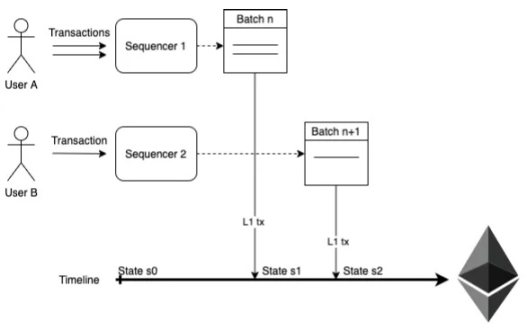

total anarchyVitalik proposed this "total anarchy

” thoughts. Anyone can submit a transaction package at any time. It satisfies the two minimum requirements for a decentralized sorter discussed above:

Sybil resistance: Sybil resistance (i.e. transaction fees and block size/gas limits) is provided by L1.

Leader Selection: Leader selection is done after the fact.

This is enough because L1 already provides security. If L2 blocks were published to L1, they will only be orphaned if they are invalid or built on invalid blocks (which will be rolled back). If they are valid and published to L1, they have the same security as L1 itself.

Based Rollup

Vitalik pointed out an important problem: inefficiency. Multiple participants are likely to submit transaction bundles in parallel, but only one can be successfully included. This wastes a lot of effort generating proofs and/or wasting gas when publishing transaction packages to the chain.

However, PBS can now make this anarchic design feasible. It allows for more regular ordering, with at most one Rollup block per L1 block, and does not waste Gas (although computing resources may be wasted). L1 block builders can include only the highest value Rollup blocks and build blocks based on bids entered by searchers, similar to any L1 block. It might be reasonable for Z to allow ZK proofs by default, to avoid wasting computation.Justin DrakeThis isBased RollupsThe recently proposed "

"The core idea behind the proposal. He uses the term to refer to a Rollup where transactions are ordered by L1 (the "base" layer). L1 proposers only need to ensure that they include Rollup blocks in their L1 blocks. This simple scheme can instantly have L1 liveness and decentralization. They sidestep tricky issues such as resolving forced transaction inclusion in the case of L2 orderer censorship. Also, they remove some of the gas overhead since no sorter signature verification is required.

An interesting question is where these L2 transactions are processed. L2 clients need to send these transactions somewhere so L1 searchers/builders can receive them and create blocks and blocks. They may be sent to:

L1 Mempool - They can be sent with some special metadata that "informed" searchers/builders can interpret. However, this may increase the load on the L1 memory pool.

L2's p2p Mempools - This line of thinking seems to be more tenable. Searchers/builders will start checking and interpreting these in addition to the usual channels.

An obvious disadvantage here is that Based Rollup limits the flexibility of the sorter. For example:

Reduced MEV: Rollups can get creative with variants of FCFS, encrypted memory pools, etc.Pre-confirmation: L2 users like fast transaction "confirmations". The "confirmation" time of the Based Rollup transaction will fall back to the same level as L1 (12 seconds), or wait for a longer time before。

Publish the complete transaction package

Interestingly, this is exactly what the early Rollup team was doing:

These are areas of research surrounding EigenLayer, at least in theirwhite paperwhite paper

mentioned in. It is unclear whether such a solution will actually solve the problem. In order for restaking to effectively ameliorate these shortcomings, it may be desirable that all stakers choose to run it. It seems more logical to emulate this idea by having stakers who want to do this enter a separate shared ordering layer (more on that later).

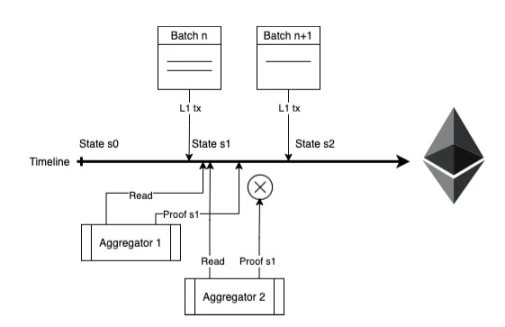

Last year, Polygon Hermez proposed a project called PoEproposalproposal

. This is another variant of ZK Rollup specifically for L1 sorting. The coordinator here is a completely open role where anyone can submit transaction packages (i.e. complete anarchy). PoE has two parties, and the process is divided into two steps:

sorter

The sequencer collects L2 user transactions and creates transaction bundles by sending L1 transactions including all selected L2 transaction data. The orderer will commit blocks based on the economic value received, or achieve a better service for the user (e.g. publish a transaction package in every L1 block, even if this makes L2 transactions more expensive, but users want more fast transactions).

Sorters will pay L1 Gas fees to publish transaction bundles, and the protocol defines additional fees that must be paid in MATIC. Once published, the winning transaction package immediately defines the new top of the chain, and any node can deterministically compute the current state. Validity proofs are then required to finalize the state of light clients (including L1 smart contracts).

aggregator

The aggregators here are ZK provers. Again, this is a permissionless role that anyone can participate in. It's simple:

Sorted transaction packets with transaction data are sorted on L1 by their occurrence position on L1.

The PoE smart contract accepts the first proof of validity to update the valid state, including one or more bundles of proposed transactions that have not yet been proven.

Aggregators can conduct a cost-benefit analysis to figure out the correct frequency to issue proofs. If they win, they get a portion of the fee, but waiting longer to issue a new proof spreads their fixed verification cost over more transactions. If the aggregator delays publishing a proof (it does not prove the new state), then the contract will perform the revert operation. Provers waste computational resources, but they save most of the gas.

Fees are allocated as follows:

Fees from L2 transactions will be processed and distributed by aggregators who create proofs of validity.

The orderer’s staking fee for creating a transaction bundle is sent to the aggregator, which includes this transaction bundle in a proof of validity.

Pure fork selection rule

RollkitSR has a similar "Pure fork selection rule"Concepts such asherehere

said, referring to a Rollup without a privileged sequencer. Nodes are sorted according to the DA layer, and the fork selection rule of "first come, first served" is applied.

Economics of L1 sorting

These L1 ordering designs have important economic implications, as the MEV of L2 transactions will now be captured at the L1 block producer level. In the "traditional" L2 ordering model, the MEV of L2 transactions is captured by the L2 orderer/consensus participant/auction mechanism. In this case, it is unclear how much MEV leaks into L1.

Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing is hard to tell:Good thing: some people like "L1 Economic Union

” (e.g. ETH gains more value).bad things: other peopleWorry

Incentives at the base layer (e.g. centralization risk for Bitcoin miners).

This type of scheme might make sense, especially as an easier rollup bootstrapping method, but it's hard to see most rollups giving up so many MEVs to L1. One of the great benefits of Rollups is indeed the economic gain - once DAs start scaling and costs come down, they will only have to pay very little to L1. The slow block times and pitfalls of the simple MEV approach also seem suboptimal for users.

Incentive ZK Proof

Note that the aforementioned PoE competition may be around the fastest aggregator. The ZK prover market has two economic problems to solve:

How to incentivize provers to create proofs

How to make attestation submission license-free, making it a competitive and robust market

Let's consider two simple models of a ZK prover market:

competitive market

A permissionless market where provers compete to create proofs for blocks produced by the Rollup collator/consensus. The first person to create a proof can get whatever reward is specified for the prover. The model efficiently finds the best-fit prover for the job.

This looks very similar to PoW mining. However, there is a unique difference here: proofs are deterministic computations. The result is that a prover with a small but consistent advantage over other provers almost always wins. Then this market is prone to centralization.

In PoW mining, there are better results in terms of randomness - if I have 1% of the mining power, I should be rewarded with 1%.

This competitive proof model is also suboptimal in terms of computational redundancy - many provers will compete and spend resources to create a proof, but only one will win (similar to PoW mining).

Turn-Based Proof

Attestations can be created in rotation among provers (e.g., based on staked tokens or reputation). This approach is potentially more decentralized, but less efficient in terms of proof latency (where one prover is able to create proofs faster and more efficiently, another "slow" prover has the opportunity to create proofs as well). However, it prevents wasting computational resources when only one prover is able to create a proof.

Furthermore, if the prover fails to provide a proof within the round (either maliciously or unintentionally), the network will experience problems. If these rounds are long (e.g., a given prover gains a monopoly for several hours) and the prover goes down, the protocol will have a hard time recovering. If the time to switch provers is short, other provers can step in.

It is also possible to allow anyone to issue proofs, but only designated provers can be rewarded in a given time. So, if the current prover fails, another prover can issue a proof, but they don't get rewarded. It's an altruistic act that spends resources doing computations without getting anything in return.

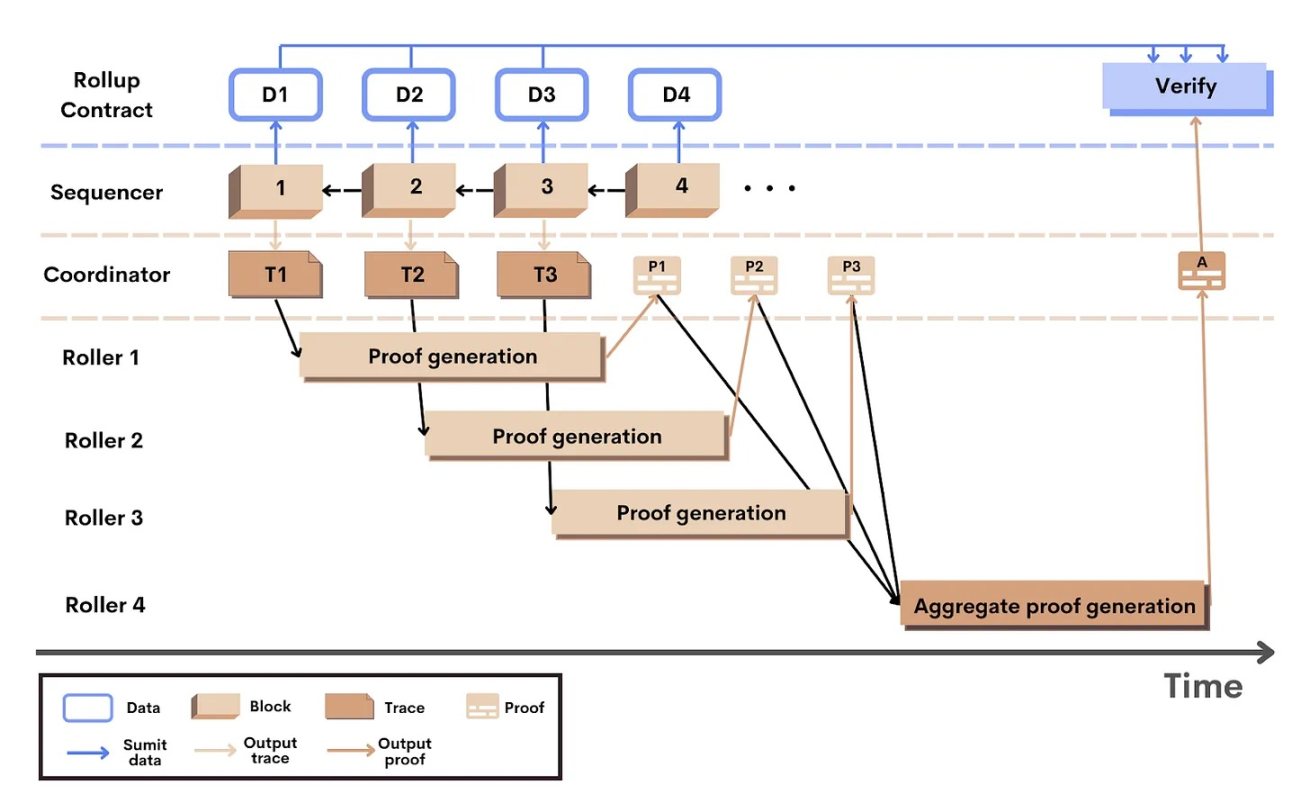

Scroll is exploring a more turn-based approach, distributing executions to randomly selected "rollers" (provers):

Scroll workflow

There are also many interesting questions, such as how user-level proofs should be charged when sorting. More discussion on these topics can be found here:Scroll's Ye Zhang in "Decentralized ZK Rollup

《The possibility of such a turn-based network based on staking + ordering MEVA is discussed in the article"Provides more details of the roller model

shared sort

shared sort

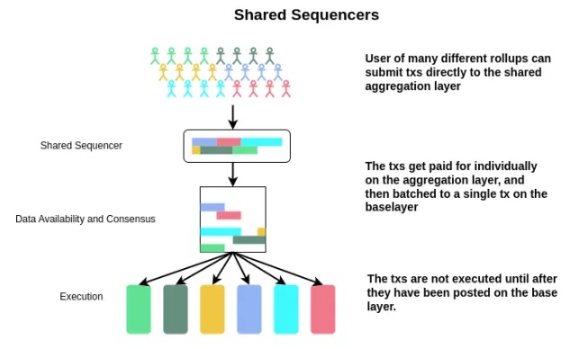

Most early solutions assumed that each Rollup would need to figure out for itself how to decentralize their sorter. As we saw in the L1 sorting scheme, it is not. Many Rollups can choose a Shared Sequencer (SS). The benefits of doing this are:

Effort-saving: No need to worry about the decentralization of the sequencer, no need to recruit and manage verifiers. This is a very "modular" approach - stripping the ordering of transactions. SS is literally a SaaS company (Sequencer as a Service).

Combining Security and Decentralization: Let an ordering layer build strong economic security (stronger pre-confirmation) and real-time CR instead of creating multiple small committees for each individual Rollup.

Fast Transactions: Other single Rollup orderers can do this too, but note that you still get those super fast pre-confirmations here.

Cross-chain atomicity - transactions are executed on chain A and chain B simultaneously. (This one is complicated, so I'll go into more depth later).

As mentioned earlier, simply using native L1 as a sorter for L2 has fundamentally several disadvantages:

Still limited by L1 data and transaction ordering throughput

Loss of ability to provide fast transactions below L1 block times for L2 users

The best that L1 ordering can do is remove the computational bottleneck of L1 (if transaction execution is the throughput bottleneck) and achieve communication complexity improvements.

So, can we design a dedicated and more efficient SS instead of letting L1 do it...

Metro - A shared sorter for AstriaMetro is a scheme of SS layer. You can refer to Evan Forbes's、Modular Insights talkresearch postShared Security Summit talkand

Learn more. The Astria team led by Josh Bowen is working on the Metro solution.

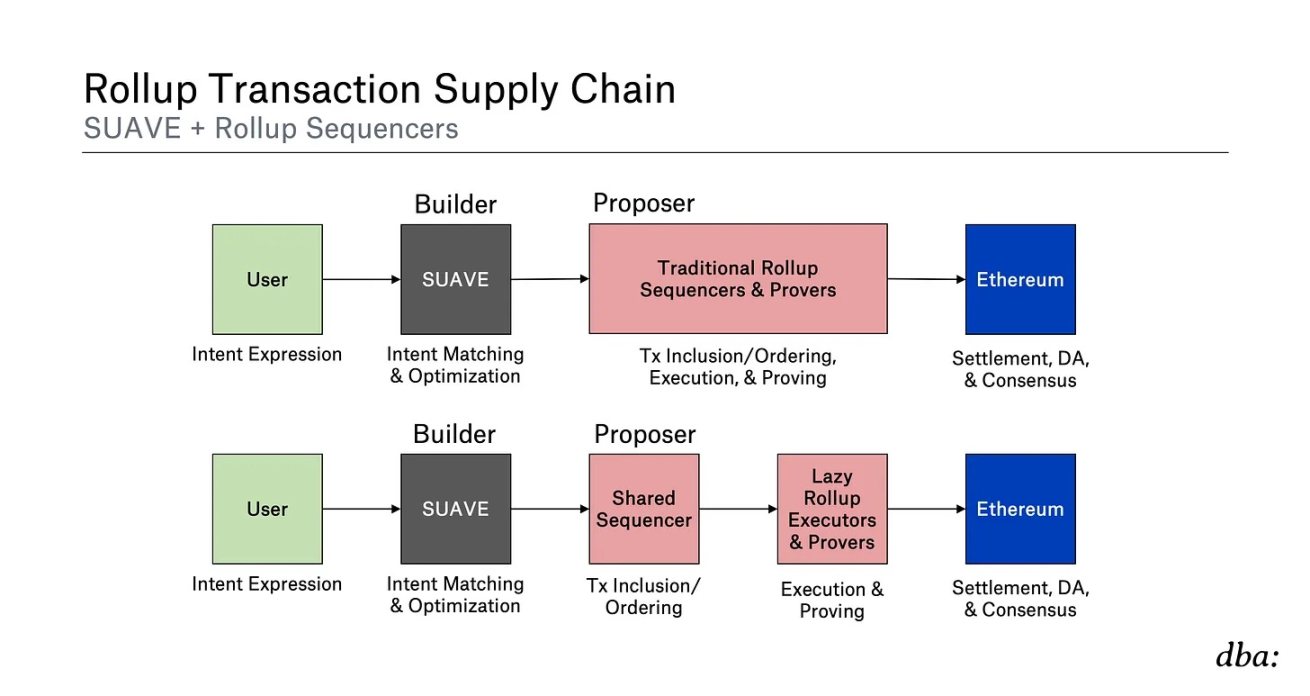

Separation of execution and ordering

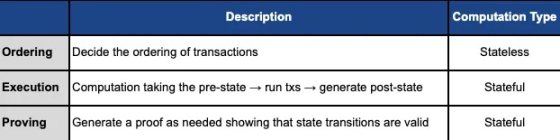

The current Rollup node actually does three things:

The key here is the separation of execution and ordering. And shared sorting can do:

Order transactions for many chains that choose to use it as an ordering layer

does not execute (or prove) these transactions and generate resulting states

Sorting is stateless. SS nodes no longer need to store the complete state of all different Rollups, they remove the execution calculation, and the huge bottleneck faced by traditional sorters disappears here.

When the execution is stripped from the consensus, the efficiency becomes very high. If all nodes had to do was generate an ordered block of transactions and agree on that block without executing everything, they would be very efficient. Execution and proof can be done after the fact by different parties.

Both sequencer security and decentralization

SS nodes can remain relatively lightweight and even scale horizontally (by selecting a random subset of consensus nodes to order different subsets of transactions). The sorting layer is more decentralized than traditional sorters, which need to grasp the complex state of the chain and be responsible for execution.

Furthermore, by pooling resources across multiple chains, instead of splitting PoS consensus across multiple Rollups, they are all aggregated in one place. Compared to many Rollups that implement their own set of sorters, this scheme may result in a more decentralized set of sorters that does not require a large amount of staked assets. This is important because:

Ranking: The first line of real-time censorship resistance (CR) and liveness for Rollup users.

Execution and Proof: Can be done after the fact without a strong need for decentralization.

Once transaction ordering is agreed upon, execution (and proof) can be deferred after the fact to an entirely different chain:

Soft Consensus and Ordering: Shared orderer provides fast pre-confirmation for users

Consensus & Data Availability: Transaction data is finalized at the DA layer for all to see

Subsequent execution layers do not need to be decentralized as this is not where CR comes from. Single orderers are not ideal candidates for CR, but not because of their role as executors, but because they order and include transactions. Here, SS already provides ordered transaction inputs, hence CR. Afterwards, the calculation and comparison of state commitments do not need to be decentralized.

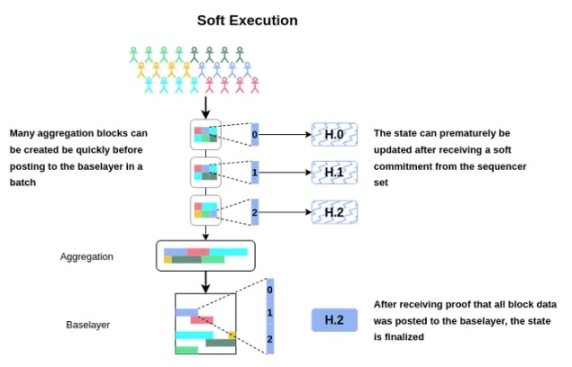

soft execution

soft execution

Users love fast soft execution:

This requires some form of consensus (or centralized orderer) to provide a great user experience:

If you just rely on the consensus of a base layer like Celestia, you can't deliver these soft promises around ordering and inclusion. If SS has a decentralized committee with staked high-value assets, it can provide fairly strong commitments on fast blocks (below L1 block times).

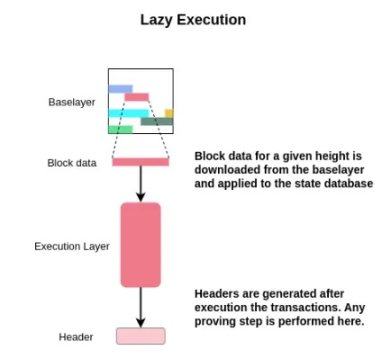

Lazy Rollup

Therefore, as long as SS creates a block, users can get soft confirmation. The strength of this confirmation depends on the construction of SS (decentralization, economic security, fork choice rules, etc.). Once the data is actually published to the base layer, you can treat these transactions as truly final. The final computation of state roots and associated proofs can then be generated and submitted.

"Lazy Rollup" is very simple. They wait until the transactions are all ordered and published to the DA layer, then they download those transactions, optionally apply fork selection rules to select a subset of transactions, perform transaction processing, and determine transaction status. Block headers can then be generated.

Note that since SS cannot generate blocks in a way that requires access to the full state, they do not check for invalid state transitions. Therefore, the "Lazy Rollup" state machine using SS must be able to handle invalid transactions. When a node executes ordered transactions to compute the resulting state, the node can simply delete the invalid/reverted transaction. Traditional Rollups that execute immediately do not have this limitation.

Rollups, which require state access to process a transaction before including it on-chain, won't work here. For example, if Rollup has a block validity rule, all transactions contained in a block are valid transactions that cannot fail. If a Rollup requires transactional forging rather than state access, then a special SS can be created specifically for this type of Rollup (eg, similar to Fuel v2 or Rollup with a private memory pool).

In order for SS to work, there must be some mechanism for users to pay for their transactions. You can simply use existing signatures and addresses already included in most Rollup transaction types to pay for gas on the SS layer. Alternatively, payment could involve some wrapped transaction on SS, where anyone can pay for arbitrary data included. This is an open design space.

Fork Choice Rules

Fork Choice Rules

Rollups are able to inherit the fork selection rules of the SS they are using. Rollup's full nodes are then actually light clients of SS, checking some commits to indicate which Rollup blocks are correct at a given height.

MEV

However, inheriting SS's fork selection rules is optional - you can simply ask Rollup to process (not necessarily execute) all transactional data it publishes to the base layer. It will effectively inherit the CR and liveness of the base layer, but you will sacrifice a lot of SS features that users love.

Assuming that a Rollup wants to inherit the fork selection rules of its SS and obtain fast soft execution, SS will naturally be at a very core position in MEV. It determines Rollup transaction inclusion and ordering.

However, Rollup does not necessarily have to execute the transactions provided by SS, or execute the transactions in the order provided. You can technically allow your own Rollup to do a second round of processing to reorder transactions issued by SS after execution. However, as mentioned above, this loses most of the advantages of using SS.

Even in this case, the SS layer may still have MEV because it has the right to contain transactions. If you really wanted, you could even allow your Rollup to exclude certain transactions in the second round of processing, but that would get messy, reduce CR, and lose most of the SS benefits.

Swap out the shared sorter

What is difficult to fork in a blockchain is any form of shared state of value. Look at ETH vs. ETC or similarly ETH vs. ETH POW, the social consensus determines what the "true Ethereum" is. The state of "truth" that we can all agree on has value.

However, SSs are really just a service provider - they have no valuable state associated with them. A Rollup using a given SS retains the ability to fork it to support some other sorting mechanism, requiring only a small hard fork (eg if the SS extracts too much value).

Espresso Sequencer (ESQ): Guaranteed by EigenLayer

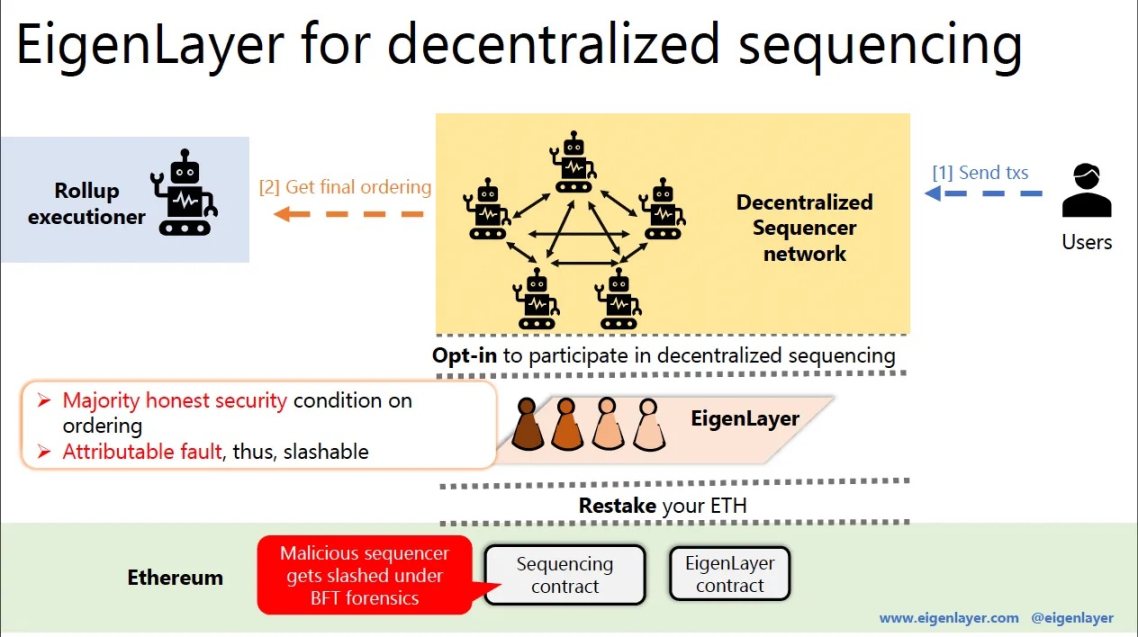

EigenLayer white paperwhite paper

Decentralized SS was mentioned as one of the potential use cases for re-staking. This SS can be secured by ETH restaking, which will handle many different L2 transaction orderings.

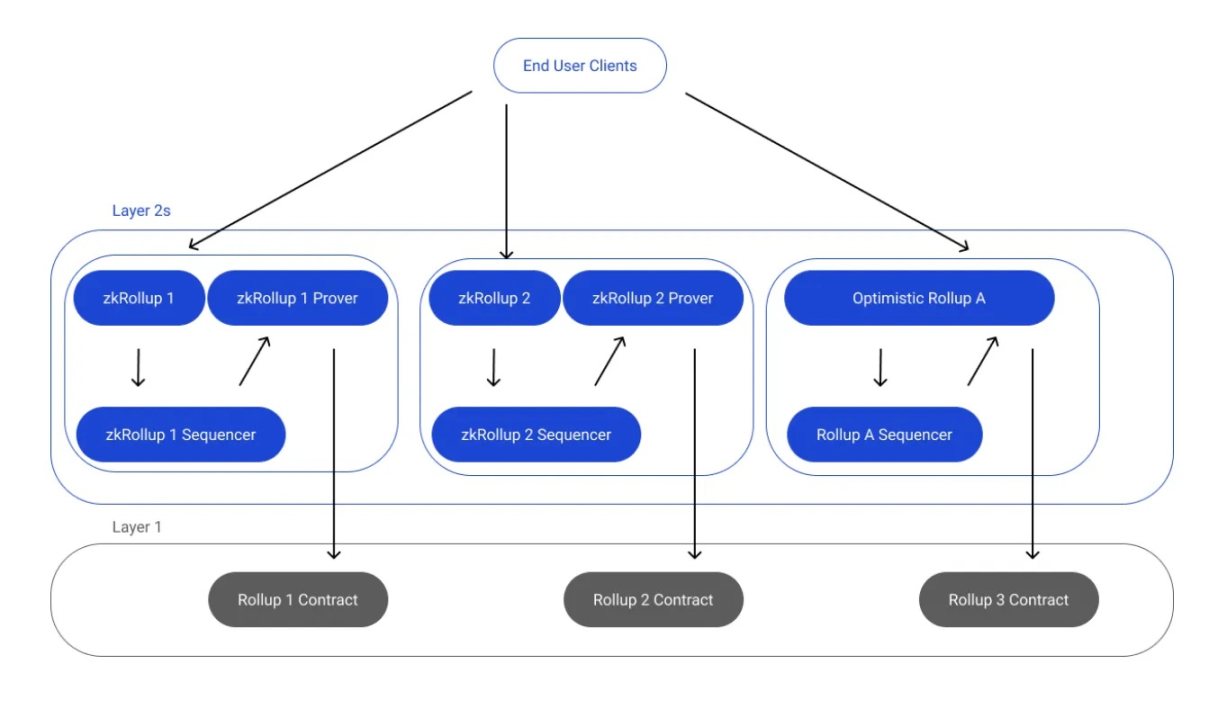

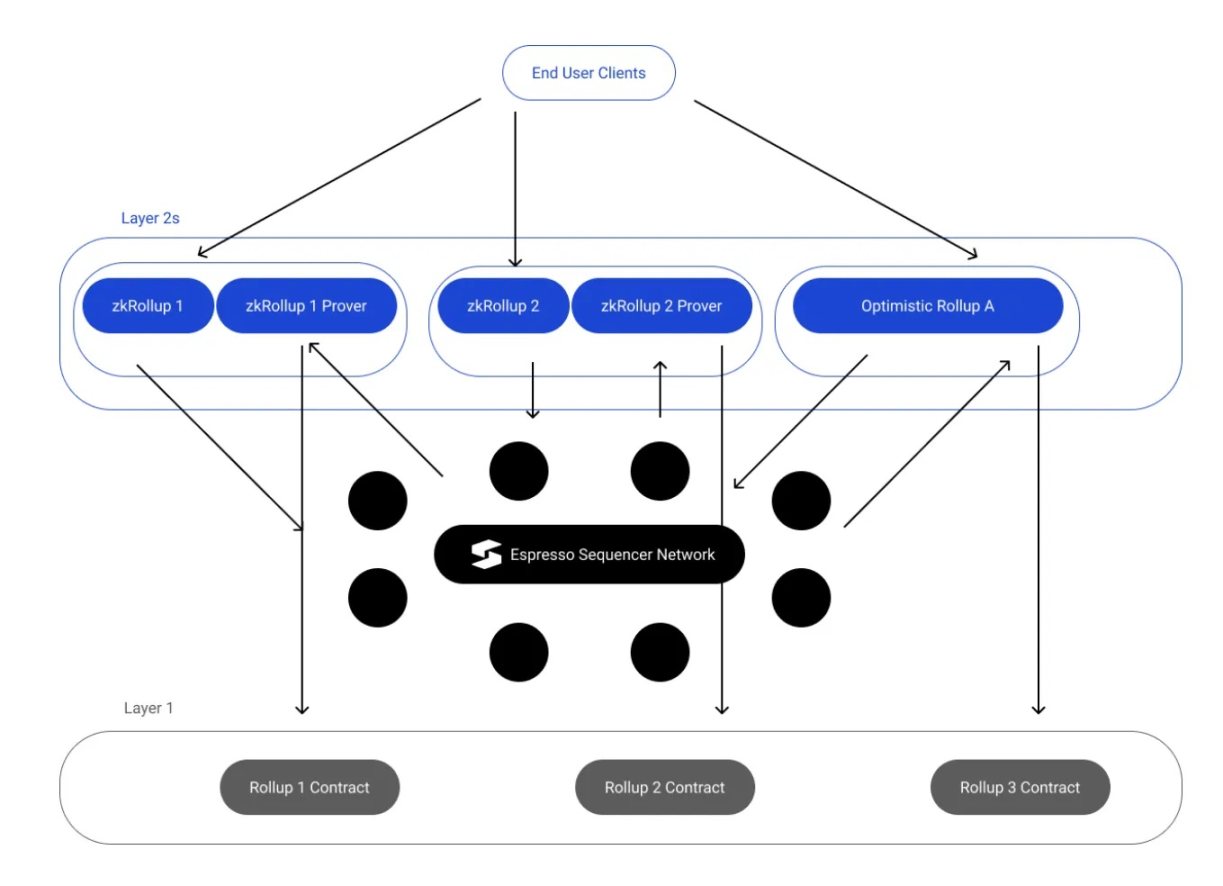

Well Espresso just announced this in their shared sequencer program. It can utilize EigenLayer re-staking to secure its consensus. To provide a nice visualization, Rollup looks like this today:

This is what they look like with SS like Espresso:

The Espresso Sequencer (ESQ) is generally very similar in idea to Metro. They work on the same core principle - decoupling transaction execution from ordering. In addition to this, ESQ will also provide data availability for transactions.

HotShot Consensus and Espresso DA (Data Availability)

For background, Ethereum currently uses Gasper for consensus (Casper FFG as finalization tool + LMD GHOST as its fork selection rule). The relevant TLDR here is Gasper's ability to stay alive even under conditions where the majority of nodes may go offline (dynamic availability). It effectively runs two protocols (Casper FFG and LMD Ghost) that together maintain a dynamically available chain with a final prefix. Gasper trades off fast determinism.

Overall, ESQ includes:

HotShot: ESQ is built on top of the HotShot consensus protocol, which, unlike Gasper, prioritizes fast finality over dynamic availability. It can also scale to support more validators, like Ethereum has done.

Espresso DA: ESQ will also provide DA for opt-in chains. This mechanism is also used to expand their general consensus.

Sequencer Contract: A smart contract that acts as a light client to verify the HotShot consensus and record checkpoints. Additionally, it manages stakers for ESQ's HotShot PoS consensus.

Network layer: Communication of transactions and consensus messages between nodes participating in HotShot and Espresso DA

Rollup REST API - L2 Rollup's API for integration with the Espresso sequencer.

This system is built for scalability, so ESQ wants to provide cheaper DA for L2. They will still settle their proofs and state updates to L1 Ethereum, but note that this will make chains using ESQ by default no longer full "Rollups" (Ethereum L1 does not guarantee their DA). It is stronger than a simple implementation of a Data Availability Committee (DAC), but its guarantees are weaker than a true Rollup.

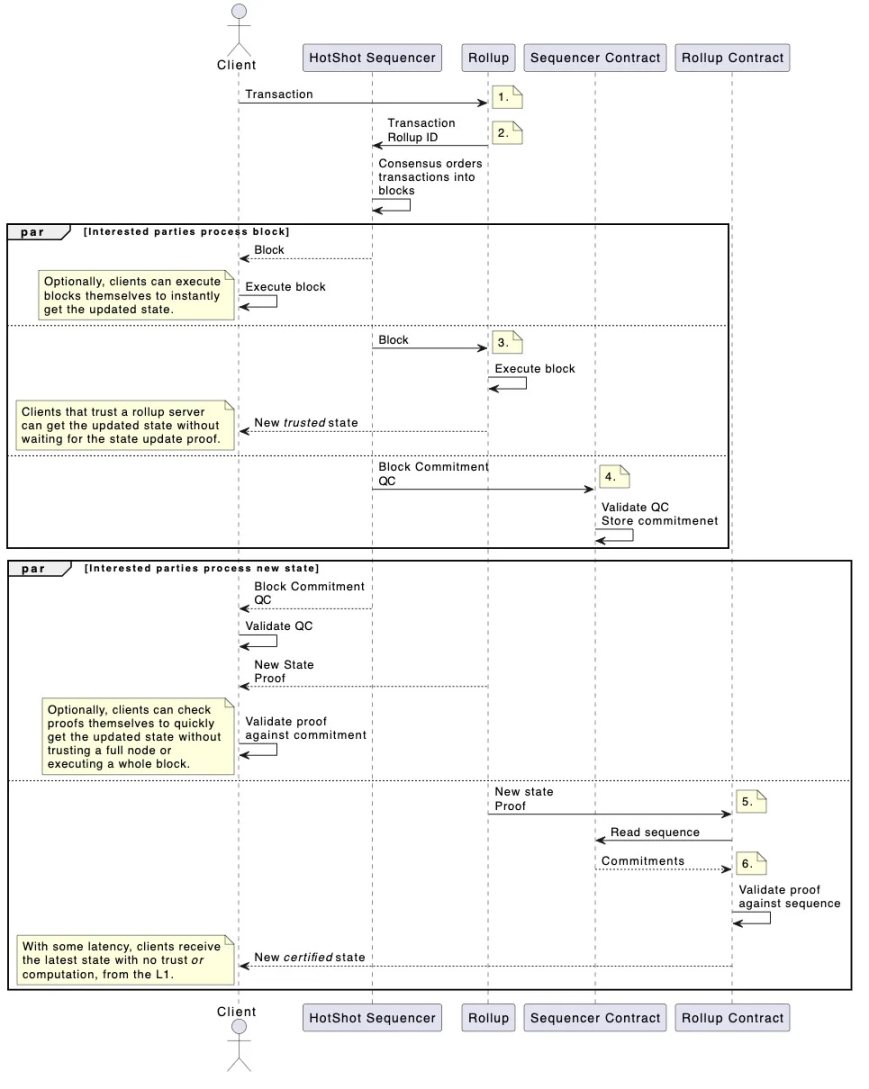

Transaction process

Transaction process

Sequencer contract: HotShot interacts directly with its L1 sequencer contract. It validates the HotShot consensus and provides an interface for other participants to view ordered blocks. The contract stores an additional log of the block submission, not the complete block, and anyone can verify the block based on the submitted information.

L2 Contracts: Each L2 using ESQ still has its own Ethereum L1 Rollup contract. In order to verify state updates sent to each Rollup (via validity/fraud proofs), each Rollup contract must have access to the authenticated sequence of blocks that resulted in the claimed state update. They interact with the sorter contract to query these.

Complete view of transaction flow:

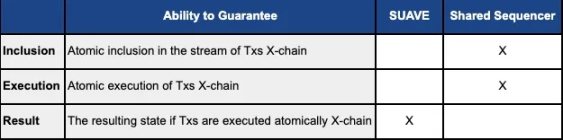

Cross-chain atomicity

Cross-chain atomicity

As stated in the Espresso post, SS can provide some exciting use cases for cross-chain atomicity:

An ordering layer shared across multiple Rollups promises to make cross-chain messaging and bridging cheaper, faster, and more secure. Eliminates the need to build a light client for another chain's sorter, saving costs. Cross-Rollup bridging can also provide further cost savings by eliminating the need for a given Rollup to remain independent of consensus in real-time from other Rollups. A shared orderer also provides a safety advantage for bridging: a shared orderer guarantees that a transaction completes in one rollup if and only if it completes in another rollup. In addition, shared orderers enhance the user's ability to express atomic dependencies between transactions across different Rollups. By convention, Alice will sign and publish her Rollup-A transaction t' independently of Bob's Rollup-B transaction t'. In this case, Alice's transaction could be ordered long before Bob's, leaving Bob with a long-term option to abort. This optionality imbalance is mitigated by a shared orderer, where Alice and Bob can submit two transactions together as one signed package (i.e., the orderer must treat the two transactions as one transaction).

This has implications for cross-chain MEV, as on-chain activity will eventually grow. A typical example is "atomic arbitrage". The same asset is traded at two different prices on two different chains. Seekers want to arbitrage by executing two transactions at the same time without risk. For example:

Trade 1 (T 1 ) - Buy ETH at a low price on Rollup 1 (R 1 )

Trade 2 (T 2 ) - Sell ETH at a high price on Rollup 2 (R 2 )

T 1 is included in the instruction stream of R 1 if and only if:

T 2 is also included in the instruction stream to R 2

T 2 is also included in the instruction stream to R 2

T 1 executes on R 1 if and only if:

T 2 also executes on R 2

T 2 also executes on R 2

However, this is still not a guarantee when you are transacting on a shared state machine (eg, fully on Ethereum L1). As mentioned earlier, SS does not hold the state of these Rollups, they do not execute transactions. You can't fully guarantee that one of the transactions (on R 1 or R 2 ) won't revert when executed.

Building higher-level primitives directly on top of this is problematic. For example, if you try to build an instant burn and mint cross-chain bridge on top of this SS, it will do the following simultaneously at the exact same block height:

Destroy the input on R1

Generate output on R2

You may encounter the following situations:

Destroy on R 1 may throw an unexpected error, but

The output on R2 is not invalidated for any reason, so it executes completely.

This will be a big problem.

In some cases, you can be sure of the expected outcome of both transactions as long as they are both included in the input stream and executed, but often this is not the case.

Guaranteed: T 1 and T 2 will be contained in their respective streams and (probably) both will be executed.

No guarantees: successful execution of the transaction and the resulting desired state.

These "guarantees" may be sufficient for something like atomic arbitrage, where the seeker already owns the assets needed to execute these transactions on each chain, but this is clearly not the synchronous composability of a shared state machine. For something like a cross-chain flash loan, it doesn't provide enough guarantees by itself.

Might still be useful when combined with other cross-chain messaging protocols. Let's see how cross-chain atomic swaps of NFTs can be facilitated when used with the Cross-Rollup messaging protocol:

T 1 transfers ETH from U 1 (User 1 ) to SC 1 (Smart Contract 1 ) on R 1

T 2 transfers NFT from U 2 (User 2 ) to SC 2 (Smart Contract 2 ) on R 2

SC 1 will allow U 2 to withdraw ETH if and only if it receives a message from SC 2 confirming that the NFT has been deposited

SC 2 will allow U 1 to withdraw the NFT if and only if it receives a message from SC 1 confirming that the ETH has been deposited

Both smart contracts implement a timelock so that if either party fails, both parties can recover their assets

SS here allows two users to commit atomically in step 1. You then use some form of cross-chain messaging to verify each other's resulting state and unlock the asset to perform the exchange.

If done atomically without SS, two parties can agree on a price. But then U 1 can submit the transaction, and then U 2 can wait and decide if it wants to abort the transaction. With SS, they are locked into the transaction.

This is almost on the verge of SS cross-chain atomicity use cases. Summarize:

The precise strength and usefulness of the guarantees offered here remain unproven

This could be very useful for cross-chain atomic arbitrage, as well as other applications such as cross-chain swaps and NFT transactions

Providing additional cryptoeconomic security (e.g., providing bonds as collateral) to underwrite certain types of cross-chain transactions may be helpful

However, you can never unconditionally guarantee transaction outcomes (you can get that by executing transactions atomically together on a shared state machine)

Optimism's Superchain- Explored the use of SS in OP chains.

Anoma - Heterogeneous PaxosandTyphonand

are very different approaches.Cross Rollup Forced Transactions。

The aforementioned Kalman's

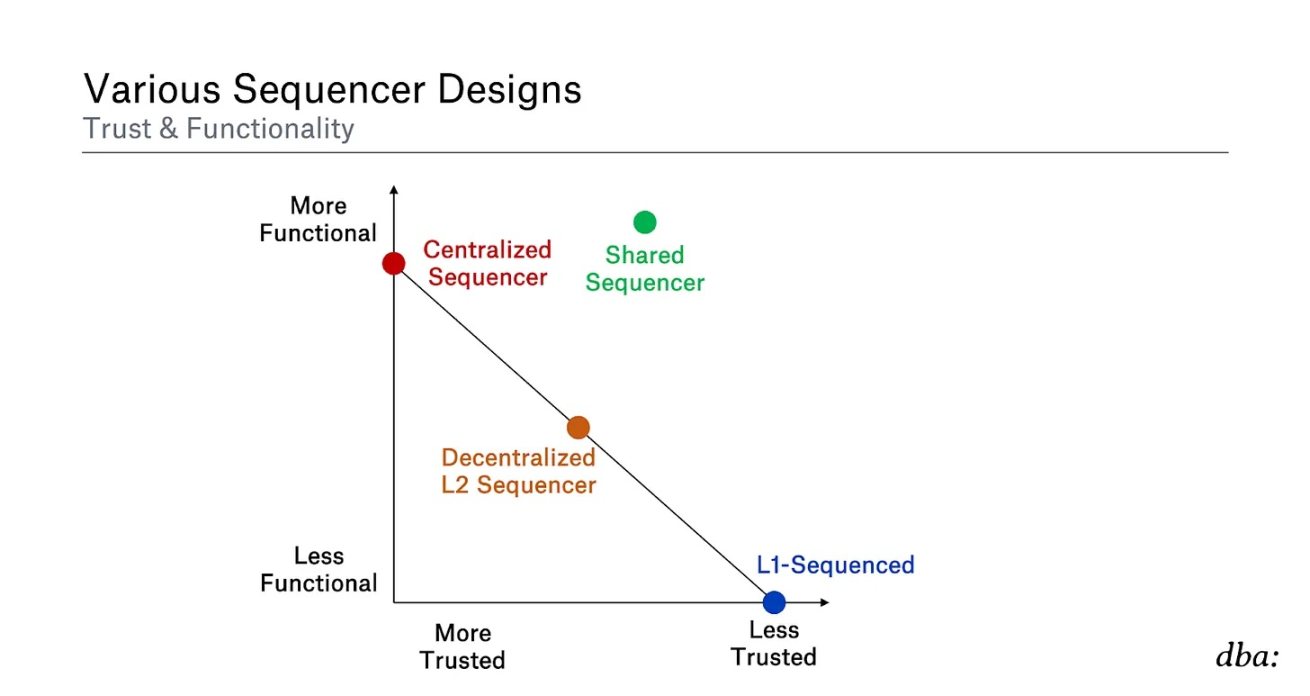

Shared sorter summary

All in all, the basic idea of SS is:

Obviously this drawing is not scientific, everything is highly subjective and very dependent on the exact build. The TLDRs are as follows:

Centralized Sequencer - If you have full control over the system, it's usually easy to implement whatever functionality you want. However, preconfirmation capabilities have suboptimal guarantees, force quits may not be desirable, liveness is suboptimal, etc.

Decentralized L2 sorter: A Rollup with a distributed pledge sorter is more robust than a Rollup with a single sorter. However, different designs have trade-offs in things like latency (for example, if many L2 nodes now need to vote before confirming a Rollup block).

Sorting in L1: maximum guarantee of decentralization, anti-censorship and activity, etc. However, it lacks features such as fast pre-acknowledgments, data throughput limits, etc.

Shared Sorter: Having the functionality of a decentralized Sorter without bootstrapping your own set of Sorters. However, this scheme has weaker guarantees in the transition period before L1 finalization compared to L1 ordering. Additionally, a shared layer can aggregate many Rollups' committees, economic security, etc. into one place (possibly more powerful than if a single Rollup had its own committee).

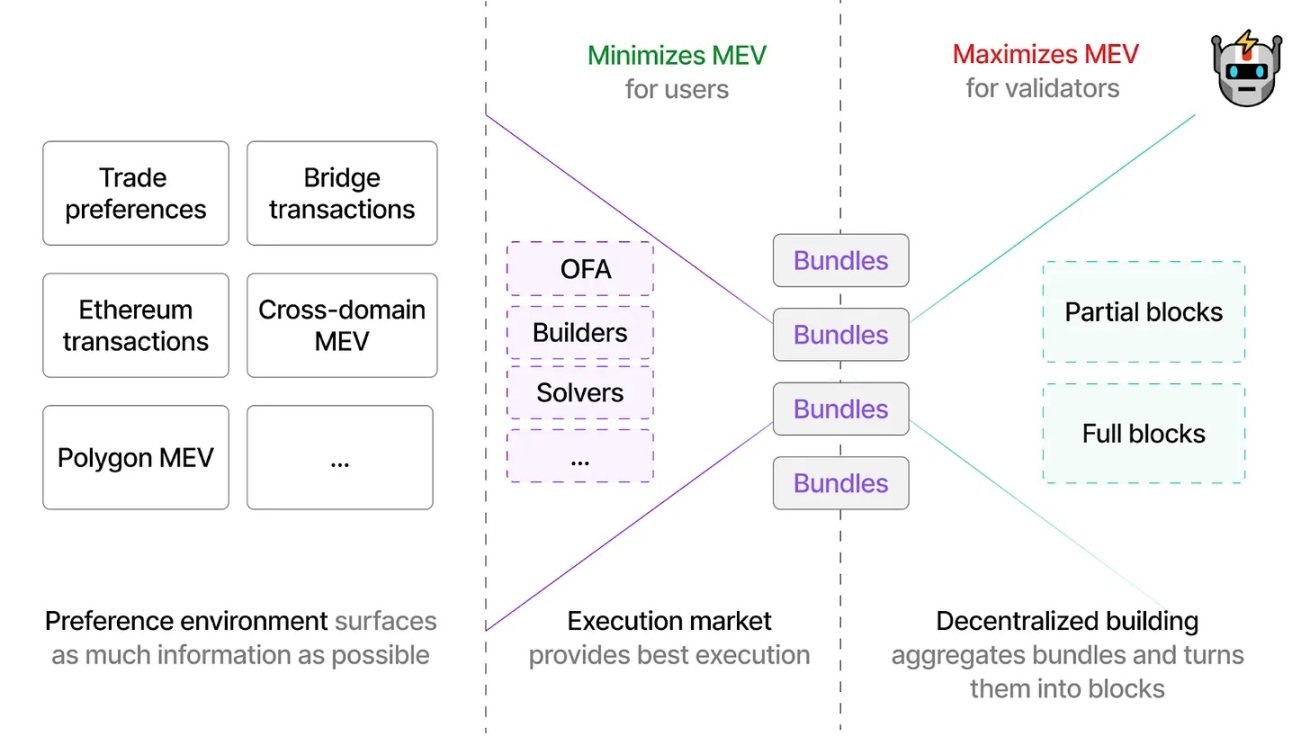

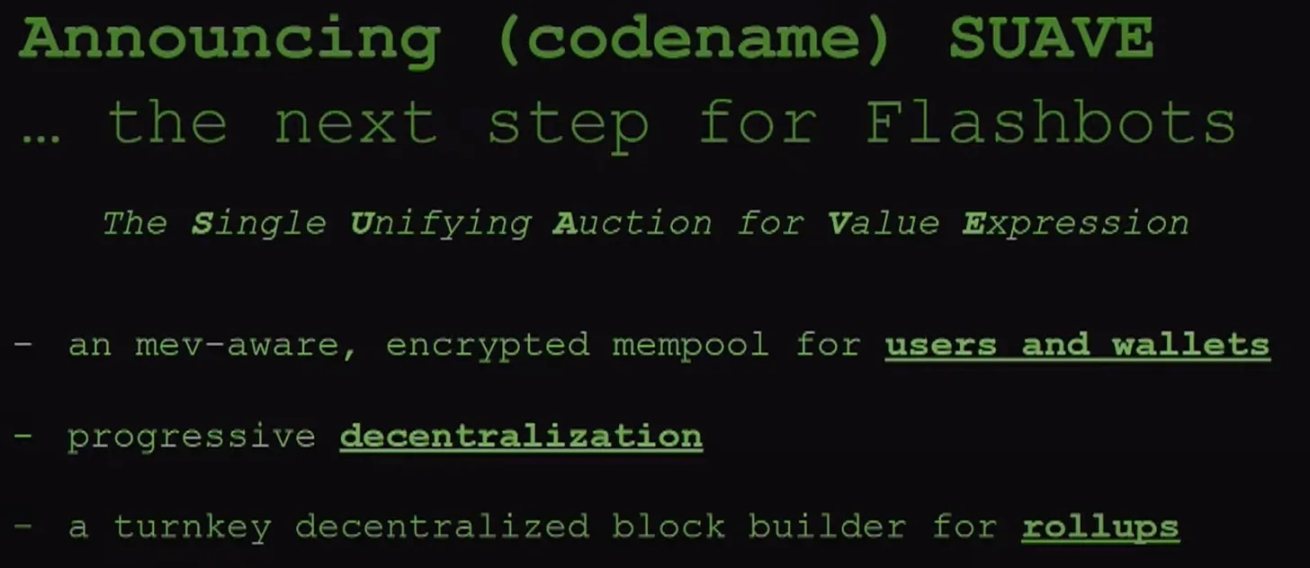

SUAVE

Once L1 is finalized, all Rollups will achieve 100% L1 security. Until the full safety and security of L1 settlement is obtained, most orderer designs only try to provide nice features, but weaken the guarantees during the transition period.

Decentralized builders and shared sortersSUAVEThe differences can get very confusing when we're talking about these shared layers that try to process transactions from many other chains. Especially when SUAVE is often referred to as an "Ordering Layer" or other terms such as "Decentralized Block Builder for Rollup". To be clear,

Significantly different from the SS design above.

Let's observe how SUAVE interacts with Ethereum. SUAVE will not be embedded in the Ethereum protocol in any way. Users simply send their transactions to its encrypted mempool. A network of SUAVE executors then outputs a block (or part of a block) for Ethereum (or any other chain similarly). These blocks will compete with those of traditional centralized Ethereum builders. Ethereum proposers choose between them.

Likewise, SUAVE will not replace Rollup's block selection mechanism. For example, Rollup can implement a PoS consensus set that operates in much the same way that Ethereum L1 operates. These orderers/validators can then choose the blocks that SUAVE generates for them.

This is very different from the SS described above, where Rollup can completely eliminate the need for a decentralized sorter. They outsource the sorting function by choosing Metro or ESQ etc., and they can choose to inherit the fork selection rules of SS. Ethereum, Arbitrum, Optimism, etc. will not change the fork selection rules because they choose SUAVE transaction ordering.

SUAVE doesn't care what your chain's fork choice rules are or how your blocks are chosen. It can provide the most profitable sorting for any chain. Note that unlike the SS nodes described earlier, SUAVE executors generally have full state (although they may also satisfy certain preferences that do not require state). They need to simulate the results of different transactions to create an optimal sequence.

To understand the difference, let's consider an example where a user wants to run an atomic cross-chain arbitrage. Submitting to SUAVE vs submitting to SS, what is the difference between the guarantees they can get:

SUAVE + shared sequencerNow think about it, how does SUAVE interact with Rollup sorting? Maybe even interact with SS? Espresso does seem to believeSUAVE and ESQ

compatible. ESQ is designed to be compatible with private mempool services such as SUAVE which can act as a builder. It looks similar to the PBS we use on Ethereum right now:

shared proposer = shared orderer

shared builder = SUAVE

Like PBS, builders can get blind commits from proposers (here orderers) to propose a given block. The proposer only knows the total utility (the builder's bid) from the proposed block, not the content.

To sum up, let’s look back at a searcher who wants to do cross-chain arbitrage. SUAVE itself can build and send to two different Rollups:

Block 1 (B 1 ) which includes Trade 1 (T 1 ) - Buy ETH at a low price on Rollup 1 (R 1 )

Block 2 (B 2 ) includes Transaction 2 (T 2 ) - Selling ETH at a high price on Rollup 2 (R 2 )

But it is quite possible that B 1 wins the auction and B 2 loses (or vice versa). What happens if you select these two Rollups into the same SS.

SS nodes don't know what the transaction is actually doing, so they need someone (like SUAVE, or another MEV-aware builder) to build a full block for them if they want to be efficient. Well, a SUAVE executor can commit both B1 and B2 to SS, provided both blocks are filled or killed (executes or deletes both atomically).

Now you can get very good financial guarantees throughout the process:

SUAVE = Shared Builder = can assure you what state would happen if both B1 and B2 were contained and executed atomically.

SS = Shared Proposer = can assure you that both B1 and B2 are included and executed atomically.

Re-stake Rollup