Vitalik: Exploring the Revenue-Evil Curve for Public Goods Funding Prioritization

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Original title: The Revenue-Evil Curve: a different way to think about prioritizing public goods funding

Public goods are a very important topic in any large-scale ecosystem, but often a difficult one to define. There are three different definitions here:

Economist: Non-excludable and non-rival goods, these two technical terms together mean that it is difficult to provide through private property and market-based means.

Layman's definition: "anything that is of public benefit".

Democracy fanatic: Contains the connotation of public participation in decision-making.

More importantly, when abstract classes of non-exclusive non-rival public goods interact with the real world, there are various subtle edge cases that arise in almost any given situation and need to be treated differently. Parks are public goods. However, if the following changes are made:

Add $5 for admission?

Fund it by auctioning off the rights to own the winner's statue in the park's central plaza?

Maintained by a semi-altruistic billionaire who likes parks for personal use and designs parks around their personal use, but is still open for anyone to visit?

This post will attempt to provide a different approach to analyzing "mixed" goods between private and public: the Revenue-Evil Curve. The questions we ask are: what are the trade-offs of different monetization approaches, and how much benefit can be gained by removing the pressure to monetize by increasing external subsidies?"This is far from being a general framework: it assumes that in a single"Community"where there is a commercial market and subsidies from a central funder"environment. But it can still tell us a lot about how public goods are funded in cryptocurrency communities, countries, and many other real-world contexts today.

secondary title

Traditional Framework: Exclusivity and Competition

Let's start by understanding how economists see which items are private and public goods. Consider the following example:

Alice has 1000 ETH and wants to sell it on the market.

Bob runs an airline and sells airline tickets.

Charlie built a bridge and charged tolls.

David produces and publishes a podcast.

Eve produced and released a song.

Fred invented a new and better cryptographic algorithm to make zero-knowledge proofs.

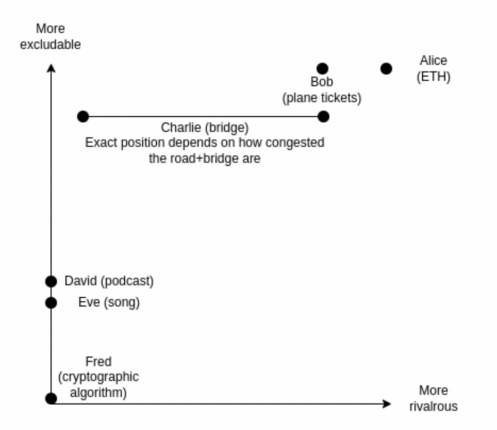

We put these cases on a graph with two axes.

Rivalry: To what extent does one person's ability to enjoy a good thing reduce another's ability to enjoy it?

Exclusion: How hard is it to prevent specific individuals, such as those who don't pay for it, from enjoying the item?

Such a graph might look like this:

Alice's ETH is completely exclusive (she has complete power to choose who gets her tokens), while crypto coins are competitive (if one person owns a particular token, no one else owns the same token )

Bob's ticket is exclusive, but less competitive: there's a chance the plane won't be full. Charlie's Bridge is somewhat less exclusive than regular tickets because adding an entrance to verify payment of tolls requires extra effort (Charlie's Bridge is exclusive but expensive for him and the user), and competitiveness depends on road congestion.

David's podcast and Eve's song aren't in competition: one listening to it doesn't interfere with the other doing the same. But kind of exclusive, because paywalls can be set up, but people can bypass the paywall.

Fred's cryptographic algorithm is almost entirely non-excludable: it needs to be open sourced for people to trust it, and if Fred tried to patent it, the target user base (crypto users who love open source) would likely reject the algorithm, or even cancel him.

This is all a good and important analysis. Exclusivity tells us whether you can fund a project by charging tolls as a business model, while competition tells us whether exclusivity is a tragic waste, or if exclusivity is just part of the good in question if one gets the other an inescapable property. However, if we take a closer look at some of these examples, especially the digital ones, we start to see that it misses a very important point: there are many business models available beyond exclusivity, and those have trade-offs.

Can we move beyond the focus on exclusivity and talk more broadly about monetization and the harms of different monetization strategies? This is exactly what the Revenue-Evil Curve is about.

secondary title

Definition of Revenue-Evil Curve

The Revenue-Evil Curve of a product is a two-dimensional curve that depicts the answers to the following questions.

How much harm must the creators of a product do to their potential users and the wider community in order to receive N dollars in revenue to pay for building the product?"here"evil

The term absolutely does not mean that any amount of evil is acceptable, and if you need to fund a project while being evil, you should not do so. Many projects hurt clients and communities by making difficult trade-offs to secure sustainable funding. But despite this, our goal is to highlight that many monetization schemes have a tragic side, and that public goods funding can provide value, giving existing projects a fiscal buffer that allows them to avoid such sacrifices.

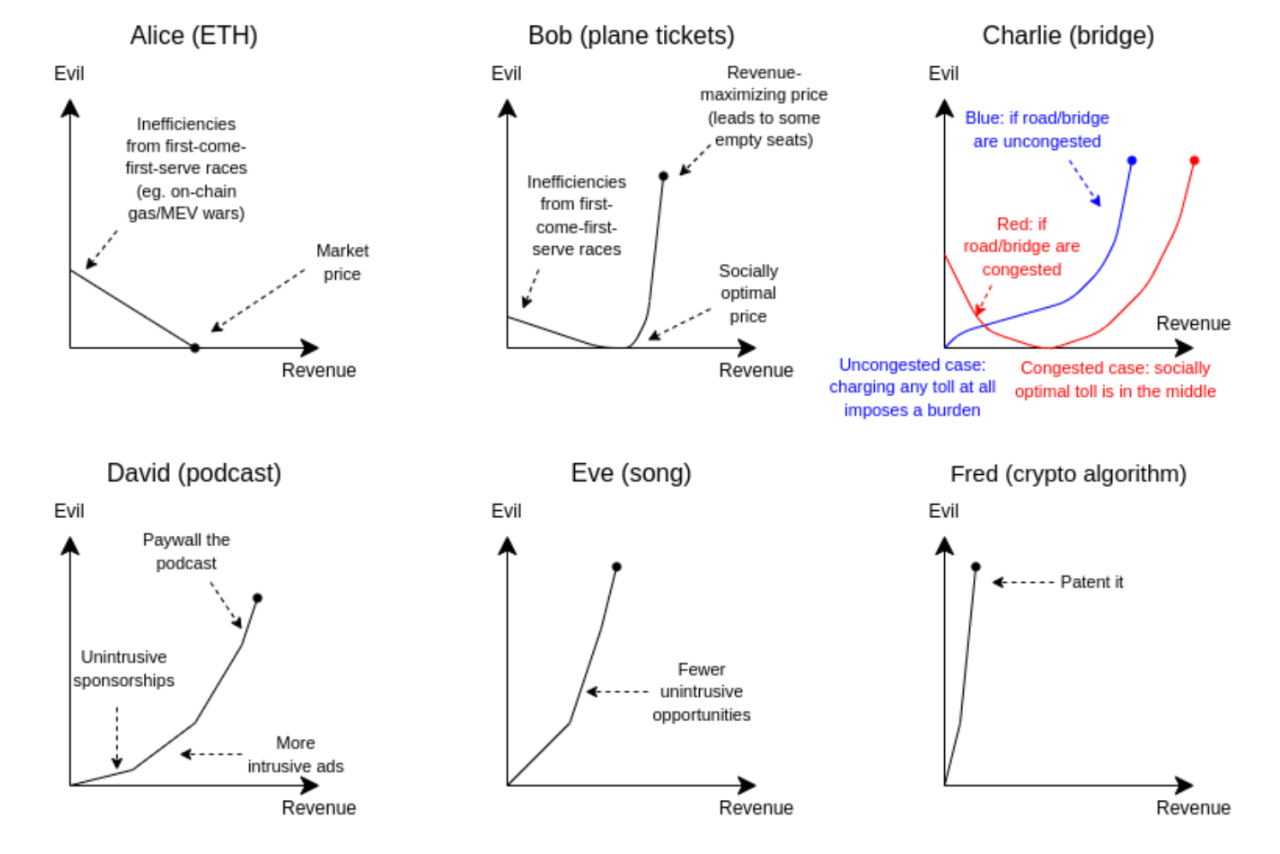

Here's a rough attempt at plotting the Revenue-Evil Curve for our six examples above.

For Alice, selling her ETH at the market rate is actually the most compassionate thing she can do. Selling it cheaper would almost certainly create an on-chain Gas war, trader HFT war, or other similar value-destroying financial conflict between everyone trying to claim her tokens as quickly as possible. Selling at an above-market price isn't even an option: no one will buy.

For Bob, the socially optimal price is the highest price at which all tickets are sold out. If Bob sells for less than that, tickets will sell out quickly, and some people won't be able to get seats at all even if they really need them (pricing too low may have some side effects, giving opportunities to the poor, but it's far from achieving this the most effective way to achieve one goal). Bob can also sell above the market price and potentially make a higher profit at the expense of selling fewer seats and (from God's perspective) needlessly excluding people.

If Charlie's Bridge and the road leading to it are not congested, charging any toll is a burden and unnecessarily excludes drivers. If it's congestion, low tolls help reduce congestion, while high tolls unnecessarily exclude people.

David's podcast could be monetized to some extent without doing much harm to listeners by adding sponsorship ads. If the pressure to monetize increases, David will have to employ more and more forms of advertising, and true revenue maximization will require charging for podcasts, which is a high cost to potential listeners.

Eve is in the same position as David, but with fewer low-harm options (maybe selling NFTs?). In Eve's case in particular, paid podcasters will likely need to actively engage in copyright enforcement and legal mechanisms to prosecute infringers, which will do further harm.

Fred has fewer profitable options. He could patent it, or maybe do something fancy like auction the right to select parameters so that hardware makers who favor a particular value bid for it. All options are costly.

What we see here is that the Revenue-Evil Curve actually has many kinds of "Evil"

Traditional economic deadweight loss excluded: If the product is priced above marginal cost, a mutually beneficial transaction that would have occurred would not occur.

Race conditions: Congestion, shortages, and other costs caused by products that are too cheap.

"Pollution" of the product in a way that attracts sponsors, but does harm to the audience to an extent (which may be small or large).

Aggressive action through the legal system increases the fear of lawyers and the need to spend money, with all sorts of unforeseen secondary chilling effects. This is especially serious in patent applications. At the expense of principles that are highly valued by users, the community, and even the staff of the project itself.

In many cases, this evil is closely tied to the context in which the events took place. In the crypto space and software more broadly, patents are both extremely pernicious and ideologically offensive, but not in the industry of building physical goods:"In the physical commodity industry, most people who are realistically able to create patented derivative works will be of sufficient size and organization to negotiate a license, and the cost of capital means that the need for monetization is much higher, so keep it pure Sex is even harder. The extent to which advertising is harmful depends on the advertiser and the audience: if the announcer knows the audience well, advertising can even be beneficial or even "exclusive"

Whether the possibility exists depends on property rights.

We may compare these cases with one another by speaking of cases of evil done for ordinary income.

What does the Revenue-Evil Curve tell us about prioritizing funding?

Now, let's get back to the key question of why we care about what constitutes a public good, not funding priorities. If we have a limited pool of funds dedicated to helping the community prosper, what should we spend our money on? The Revenue-Evil Curve graph gives us a simple starting point for the answer: direct funds to those projects with the steepest slopes of the revenue-evil curve.

We should focus on those per-dollar subsidies that minimize the evil needed for hapless projects by reducing the pressure to monetize. This gives us an approximate ranking."First: the most important"pure

Public goods, because there is usually no way to monetize them at all, or even if there is, the economic or moral cost of trying to monetize them is very high."Second: the priority is"natural

public goods, but they can be financed through the adaptation of commercial channels, such as the sponsorship of songs or podcasts."Third: priority is non-commodity private goods, social welfare is already optimized through fees, but profit margins are high, or more generally there is opportunity"pollute

products to increase revenue, for example by keeping companion software closed-source or refusing to use standards, subsidies can be used to push these projects to make more pro-social choices at the margins.

Note that exclusivity and rivalry frameworks often lead to similar answers: first focus on non-excludable and non-rival goods, second on excludable but non-rival goods, and finally on excludable and partially rival goods -- And excludable and competitive goods will never be concerned (if you have spare capital, it is better to issue it directly as UBI).

There is a rough approximate mapping between the Revenue-Evil Curve and exclusivity and rivalry: higher exclusivity means a lower slope of the Revenue-Evil Curve, while rivalry tells us whether the bottom of the Revenue-Evil Curve is zero or non-zero. But the Revenue-Evil Curve is a more general tool that allows us to discuss the trade-offs of monetization strategies that go far beyond exclusivity.

We can understand this disagreement as a Revenue-Evil Curve controversy: I think Wikimedia has a lower Revenue-Evil Curve slope (“ads aren’t that bad”), so they are a lower priority in my philanthropic funding; Others believe that their Revenue-Evil Curve has a high slope, so they are the top priority for Wikipedia's philanthropic funding.

secondary title

Revenue-Evil Curve is an intelligence tool, not a good direct mechanic

One important conclusion not to draw from this idea is that we should try to use the Revenue-Evil Curve directly as a way of prioritizing individual items. Our ability to do so is severely limited due to monitoring constraints.

secondary title

in conclusion

in conclusion

Exclusivity and rivalry are important dimensions of a commodity that have a very important impact on its ability to monetize itself and answer the question of how much harm can be avoided through public funding. But especially once more complex projects enter the fray, these two dimensions quickly start to become insufficient in determining how funding should be prioritized. Most things are not purely public goods: they are some kind of hybrid in the middle, which can become more or less public in many dimensions, not easily mapped to "exclusion".