Delphi Digital 4D long article: Where will blockchain games go?

Original author:Delphi Original author:

Original compilation: Fries @WhoKnows DAO

first level title

1 Introduction

By now, it’s no secret that most gamers hate cryptocurrencies. We've seen community backlash against Ubisoft Quartz and Dr DisRespect's Midnight Society, among others. There are good reasons for game commentators such as Asmongold and Josh Strife Hayes to continue to pay attention to the encrypted game track. You might be surprised to hear a crypto-native company (referring to Delphi Digital) admit this, but we understand where this backlash comes from and believe it is well-founded.

As a team of gamers and the earliest supporters of blockchain games, the denial of blockchain games really caught people off guard. Initially, we thought it was because people didn't understand the benefits that cryptocurrencies could bring to gaming. We've also listened to and had many debates over time.NORAfter much discussion, we believe that many of the criticisms that surfaced have merit. Not just crypto games, but more broadly, the evolution of monetization methods and practices at the core of the games industry over time. In this article, we will share the insights and theory of evolution that these critiques have helped to shape. To provide historical context for where we are in the games industry, share some reflections on the entry of crypto into games, and construct a few models for where we think cryptocurrencies are in games. In particular, we will explore the work by Brooks Brown andThe team developed a new model called PlayFi. Readers are strongly encouraged to watch our Disruptor's Episode with Brooks BrownPremiere

. Building on many of the principles discussed in the show, we have constructed the ideas in this article, with some modifications based on experience.

2. Why a game

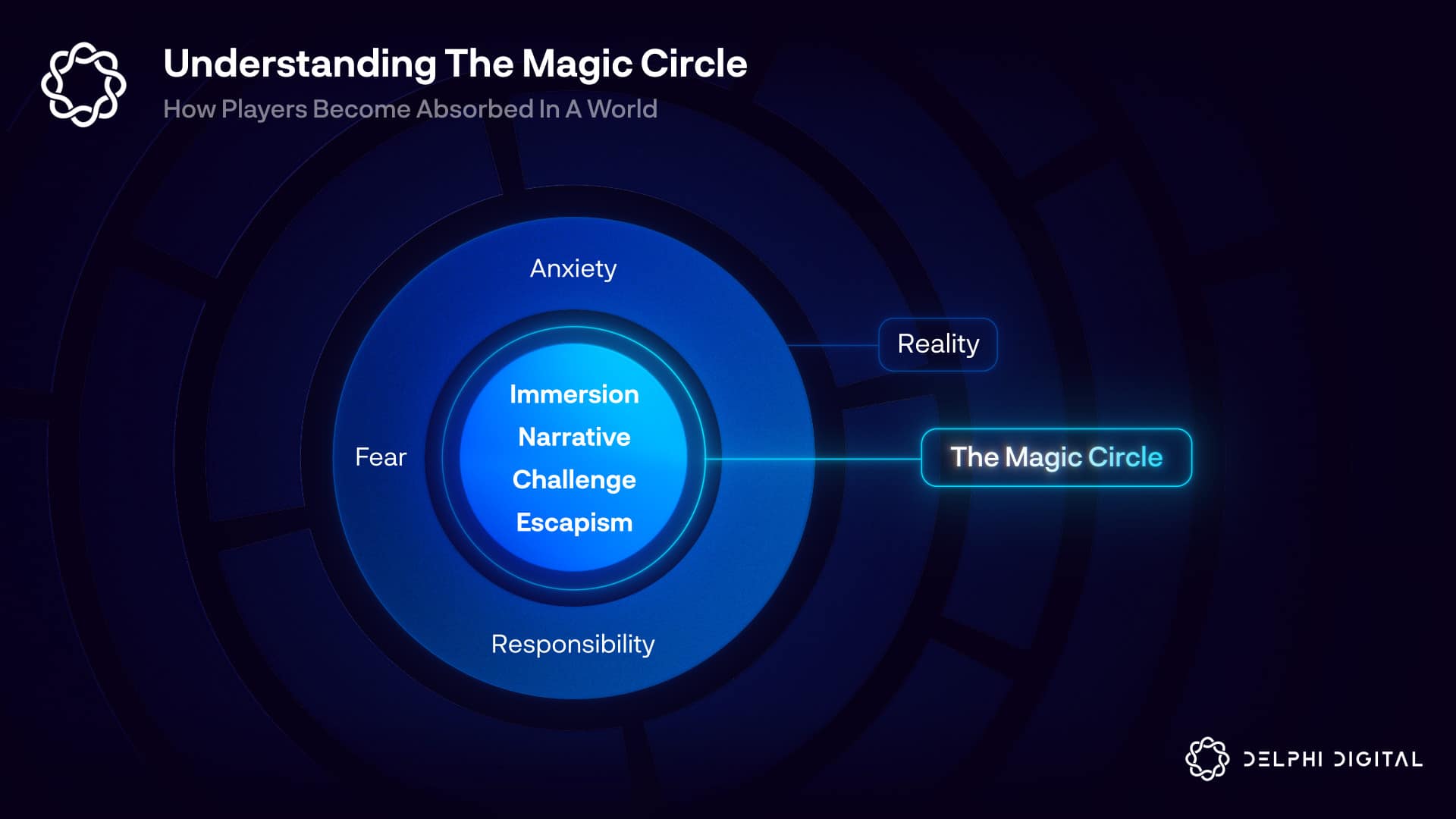

First, it's worth narrowing down and building a higher-level framework to understand why people are drawn to games in the first place. Let's start with the concept of the "Magic Circle", first pioneered by Johan Huizinga in his 1938 book Homo Ludens and later by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman in their 2003 book The book Rule of Play: Fundamentals of Game Design expands on design in the context of games.

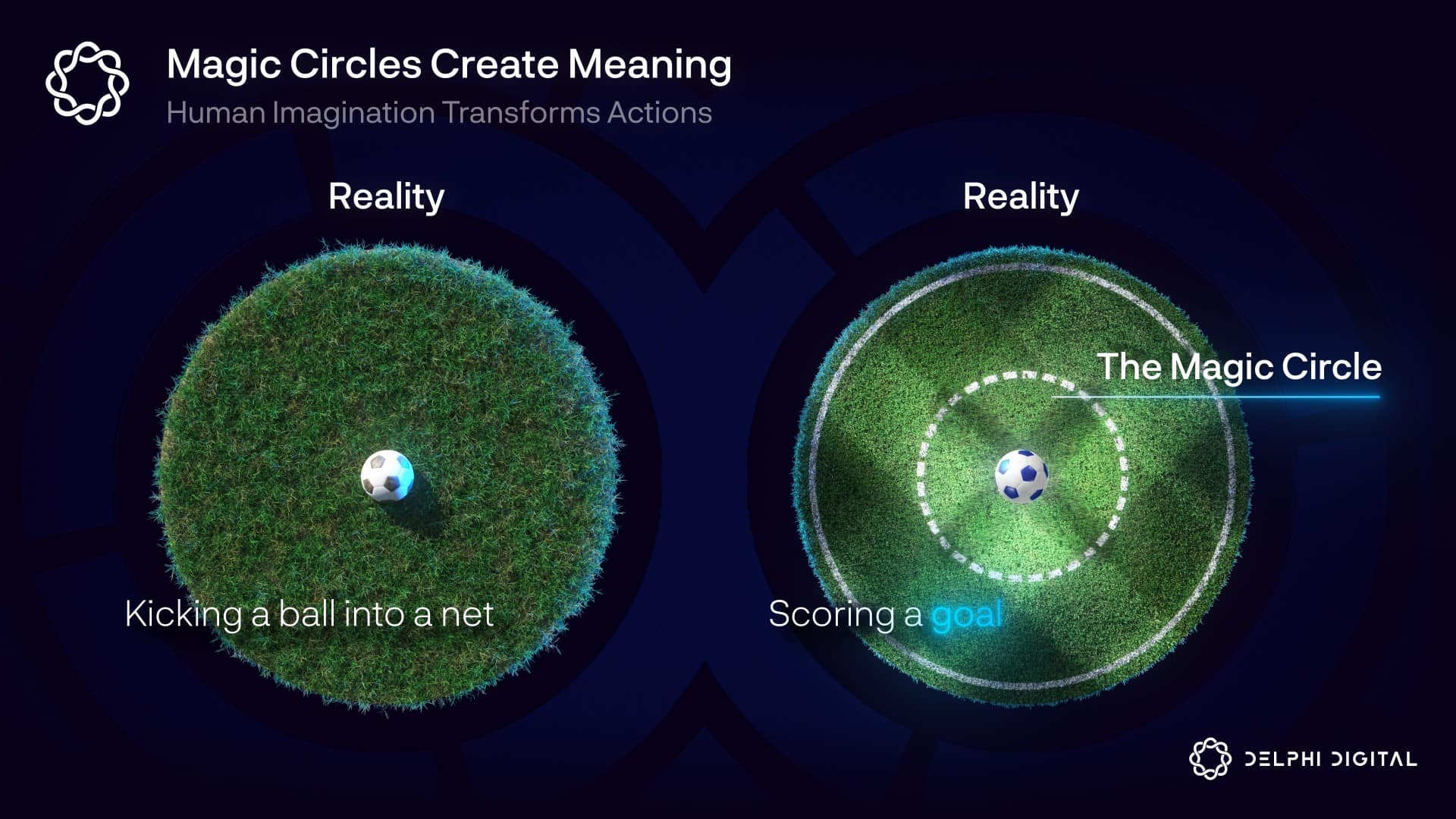

The term "magic circle" refers to the imaginary boundary between the real world and the game. Reality, often with its unfortunate baggage and limitations, is where many people wish to escape. The game's magic circle can provide them with this safe haven. Due to the extraordinary nature of human imagination, seemingly mundane actions can take on extraordinary forms within the "magic circle". For example, the simple act of kicking a ball into the net can be completely altered. Maybe that ball into the net actually represented a winning goal in the World Cup final. Suddenly billions of people care about this moment, a moment of great and lasting significance. The difference here is that it takes place within a "magic circle", a shared illusion, and society takes it seriously.

It might surprise you that we used a sports example in a post about video games, but they have far more in common than they differ from each other. Throughout human history, sports have been a major entertainment medium. Recognized worldwide as an important source of meaning, capable of evoking great passion and localism on a global scale. Sports are respected because people understand the skills involved in truly excelling, usually by practicing the sport themselves. Plus, they've evolved over thousands of years to optimize what people actually enjoy and love in games. The result is a very specific model around game monetization, which we'll explore later.

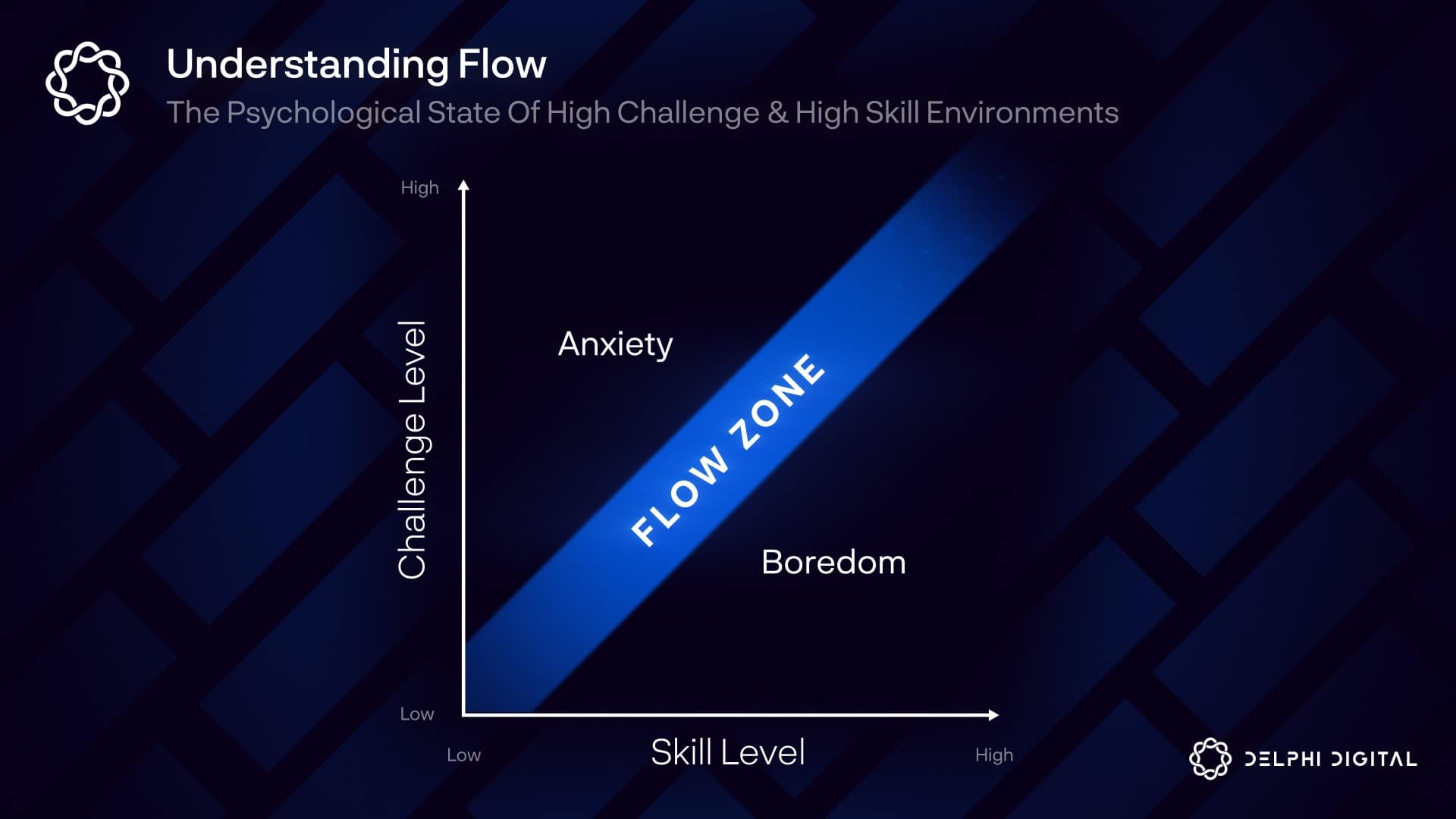

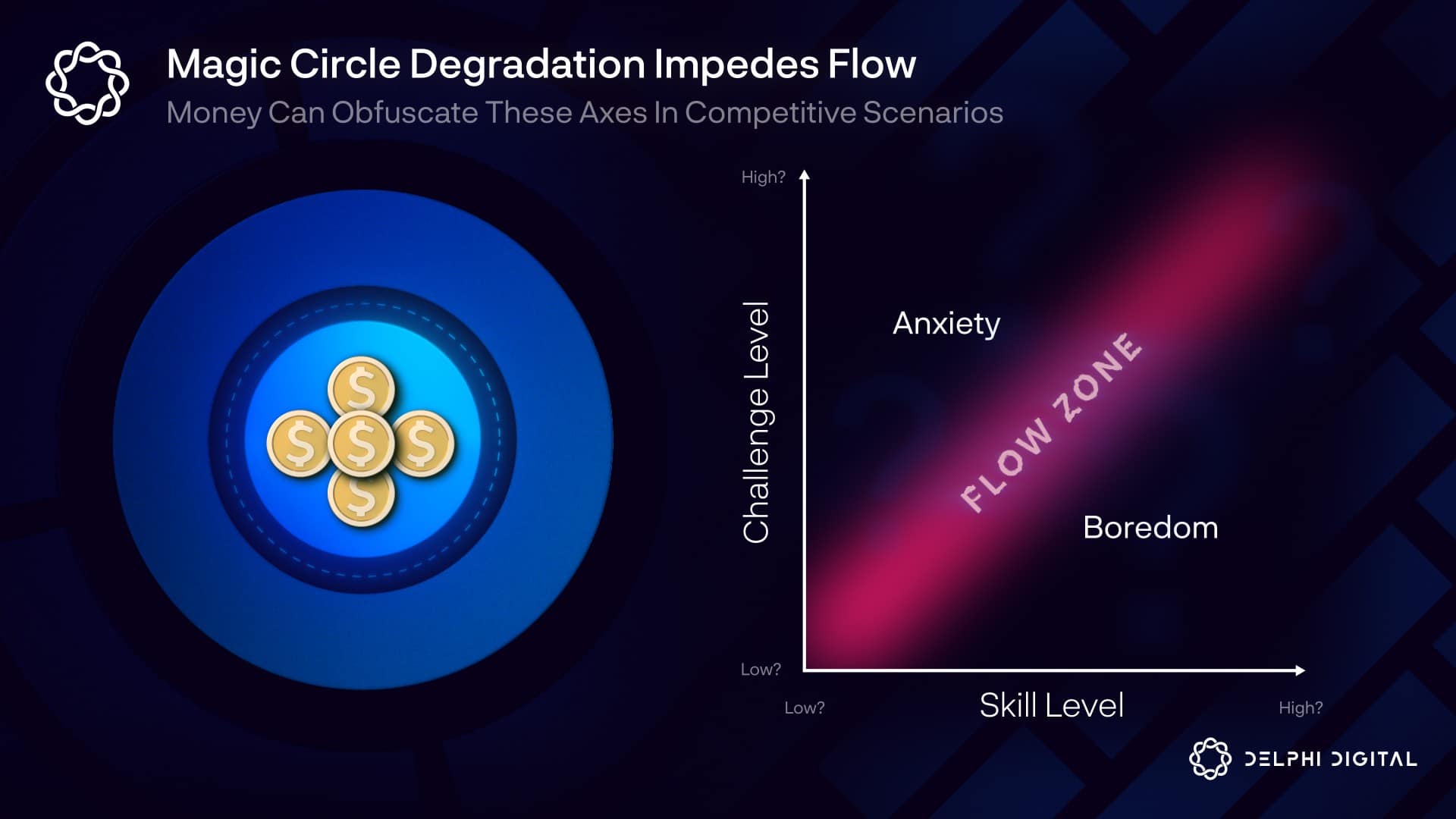

Going back to the concept of the "magic circle", it often induces a flow state - a well-studied psychological phenomenon that extends far beyond games or sports. This is the state that arises in situations of high challenge and high skill. To successfully craft an engaging magic circle, the player should be so engrossed in the experience that all other needs become trivial. The outside world necessarily fades into the background. Chances are you've experienced that "being in it" feeling. This is what many people love about video games - what games are really about.

This is the last point where everything starts to fall apart in the current generation of video games. In many cases, gaming is not immune to external distractions. In fact, it has become entangled with arguably the greatest constraint that reality imposes on people: money. We believe this is a big source of hostility towards cryptocurrencies among mainstream gamers. Parts of the traditional gaming industry are prone to aggressive monetization practices that sometimes hurt the player experience. Therefore, when gamers see that they need to buy NFT to participate in encrypted games in the early stage, or when large game publishers announce plans to develop in this field, they will think that this is another attempt to "grab money" and try to avoid it.

The above problems are most evident in competitive multiplayer games, where some players pay for game performance to beat other players, eroding real competition. These games are often labeled pay-to-win (P2W) and rightfully receive backlash. With the advent of cryptocurrencies, and the ability to tokenize and trade game assets, many commentators worry that blockchain gaming will always be headed in this direction. While this is a valid view, we believe it is a one-dimensional view that misses many of the great opportunities that cryptocurrencies can enhance the gaming experience.

To summarize some of the key points we covered:

People play games as a form of escapism; flow state and immersion enhance this.

Skill-based competition can be an important driver of what makes a game meaningful.

Paying can break the above when it affects the core gameplay.

We believe that much of the criticism in the gaming industry against both crypto and traditional games stems from the way games are monetized. In an ideal world, one could argue that to create the most immersive gaming experience, money must be limited to the core gameplay. That's not to say all forms of monetization are bad, but we should be looking to monetize in a way that doesn't harm the core game loop or true competitive play. It’s not that it can’t be a game that pays to touch the core gameplay, because this type of game definitely has an audience. It is worth noting that these different models are all within the scope of monetization methods and can be handled in a variety of ways. As ever, there is no one-size-fits-all solution and there will always be nuance in the infinite space of game design.

3. History of game monetization

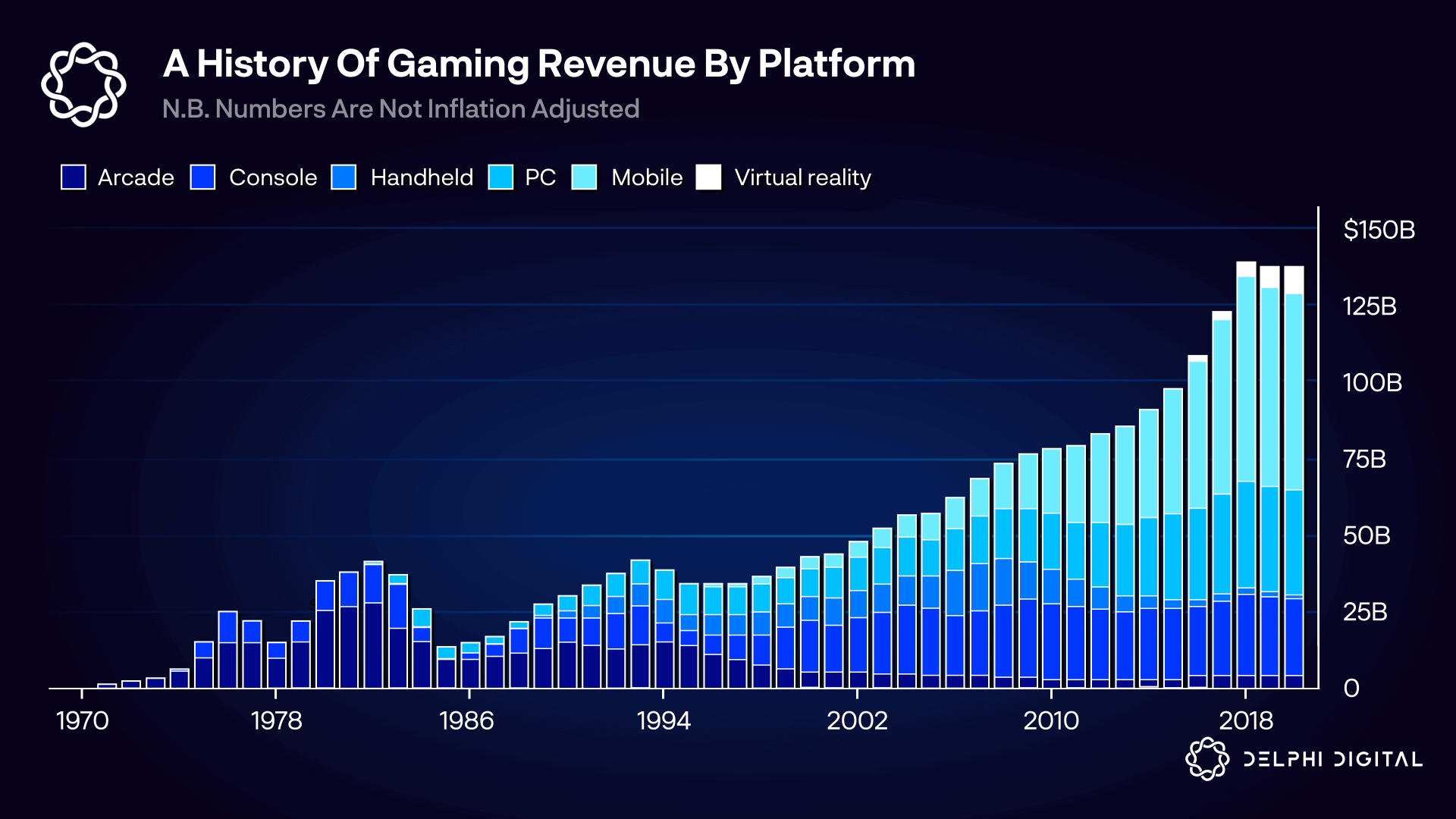

Before we explore the current incarnation of cryptocurrencies in gaming, it’s worth thinking about the industry’s history within the context provided above. The video game industry has been in a long evolution as a mainstream phenomenon since the late 1970s, when arcade games ushered in gaming's first golden age (1978-1982). These early games exuded the light of the soul, and the public spectacle of the arcade unleashed the strong competitiveness of the game industry for the first time. The quest for high-score slot machines and the glory that can be shown to friends and foes alike is contagious. These games are skilled, fun, and follow the old adage that great games are easy to learn, hard to master.

Given the seemingly ubiquitous nature of modern video games, it might seem counterintuitive that the revenues of the early game industry rival those of the more recent past. In 1981, the video game industry had $20 billion in revenue. That's close to today's $64 billion when adjusted for inflation. For context, global games revenue in 2021 is $180 billion. Despite the antagonistic factors associated with the games industry at the time, the success of video games was impressive. Having to carry coins with you, wait in line in chaos, make sure the machine is working, make sure the game is running is intolerable for modern gamers. So novelty aside, what was the magic behind these early games?Brooks Brown atSpeaking of NOR

At the time, the concept of "fair competition and thrill of adventure" was emphasized. The core idea is that, early on, the game offers real risk. Walk up to the front row of the arcade, and the quarters will give you a chance to play Three Lives. When you run out of three lives, you're out. With cash value intertwined with skills, there is a real incentive for players to keep improving their skills. Better players live longer, so they really get their money's worth. The greatest players are rewarded at the highest level in the form of high scores, and their achievements can be immortalized - after all everyone understands how hard it is to earn a top spot on the scoreboard, so it deserves respect.

The incentive structure drives players to want to get better by practicing more, which can only be achieved by investing more money. Importantly, the fairness of the game is also sacrosanct. There are no cheat codes, purchasable power-ups, or other consumables to give players an advantage. These games are primitive forms of competition where all variables other than the environment are within the player's control. Unlike a lot of what we see in modern games, users can guarantee that they can win these games through sheer skill alone. It’s what Brooks calls “fair play and the thrill of adventure.”

As the industry grew, the advent of home consoles took gamers out of the arcade and back into the comfort of their own homes. They can now play any game they want, anytime, anywhere, without the constraints of the earlier arcade days. In the years between the rise of consoles and the advent of the Internet, the public spectacle of arcades and the competitive spirit surrounding high scores waned. These top "virtual gamers" used to capture large audiences, but that energy has now dissipated. In the new era of gaming, losing three lives and "death" don't have the same meaning, as players can simply respawn for free without any real-world penalty. Because losing is less important, winning becomes less important. The consequences of actions have changed.

As Brooks puts it, "risk devaluation cuts the link between player skill and entertainment value". Eventually, game designers became more reliant on technological advancements, such as better graphics and sound, to distract users from such subtle but important changes. Hereafter, a perpetual cycle of infinite rebirth from the comfort of your own home will be the norm. The former name of NOR was actually Eternal Return, named after Nietzsche's fatalism that was destined to exist so repeatedly.

By the mid-1980s, video games were growing rapidly, and production budgets continued to increase, allowing larger games to be produced with increasingly complex mechanics and longer storylines. The industry no longer competes directly with sports, but tends to compete with film and television. Over the decades, we've seen this general trend toward higher-value games, with Netflix's Q4 2019 investor letter stating that "We compete (and lose) more with Fortnite than with HBO's." more competition".

In the '80s, '90s, and new millennium, the gaming industry was dominated by triple-A titles—games that required a substantial upfront cost, typically $60, to play. These games are distributed on CDs or cartridges and run on consoles such as the PC, Play Station, or Nintendo GameBoy Advance. The existence of these games depends on developers willing to pay an "enthusiasm premium" and sleep under their desks after working 100 hours a week.

The "premium gaming" business model means that only players who (1) have the requisite hardware (console or PC) and (2) have $60 to spend on a personal gaming experience can play these video games. While these experiences are precious, video game accessibility remains limited worldwide—as of 2001, the top-selling video game: Pokémon Gold, Silver, and Crystal, sold just 3.1 million copies. In comparison, Garena: Free Fire has more than 100 times the number of users and today has 311,250,355 monthly active users.

Additionally, value capture for game developers is limited—the inability to effectively differentiate price means players willing to pay thousands of dollars for a gaming experience don't have any meaningful way to spend that budget. This has changed significantly with the advent of free-to-play and mobile games.

Mobile games and the free-to-play model have propelled the gaming business to dizzying new heights. Today, mobile gaming revenue ($85 billion) exceeds PC ($40 billion) and console gaming ($33 billion) combined. Taking advantage of digital-first game distribution, the industry tends to let games start for free. This opens up the game to over 3 billion people around the world. While the game is free to launch, the game still has to be monetized to be funded. The mobile age has led to two main strategies: advertising and, most controversially, microtransactions — which involve charging people extra to gain in-game advantages: convenience, time savings... and power over other players.

While harmless in the beginning, as most monetization happens on items and other purchases that don't affect game balance, it has changed in many cases. The game is designed and developed with a behaviorist rather than a comical perspective in mind. The approach to making gaming a venture-backed industry means a race to the bottom. By focusing on improving retention, before monetization layers, the free-to-play game industry has spawned a set of behaviorist mechanisms that rely on the psychology of addiction to retain and monetize players. These include appointment mechanics, and the careful use of notifications and social features to keep players checking in.600,000On the dark side of the spectrum, game developers deliberately create obstacles and uncomfortable situations for players to encourage them to spend money to overcome them. For example, by allowing resources to be stolen, players are encouraged to buy shields to protect their resources while offline. Also, since many games rely on "capturing" big spenders (whales) for profit, a game's success also depends on its economic depth, or how much the whales can spend on those games. For example, fans of Diablo Immortal might spend up to

Dollars completely level up a character. Some parts of the current industry prefer to allow pay-to-win, intentionally worsening the gaming experience for non-paying players.

This is especially corrosive in multiplayer games. In this game, whale players gain a sense of superiority through an unfair advantage. The market has spoken, and this business model is clearly extremely attractive to many developers. Unfortunately, some studios have gotten too aggressive with this model and created serious antagonisms with their player base, who view the game developers' actions as predatory. Again, the extent to which developers adopt these practices varies and ranges from acceptable to extreme.favorableof.

of.

All in all, with a classic S-curve, every aspect of the gaming industry has shifted from user acquisition to value extraction. Many monetization practices have become so entrenched that everyone is forced to succumb to the same tricks. We’ve seen design at the monetization level stagnate, as the various psychological tricks to attract people become more formulaic over time. Instances of microtransactions and pay-to-win can erode the concept of a "magic circle", which can lead to confusing axes of flow and ultimately ruin the player experience. Cryptocurrencies show the next step in the evolution of monetization in games, and in the next sections we'll explore how these early implementations took place.

4. Blockchain in games

Before we dive into the current generation of crypto games, it’s worth reviewing some properties of blockchain technology that we think will be interesting when applied to games. Below, we will analyze these advantages from the perspective of players and developers.

For players, we see the following advantages:

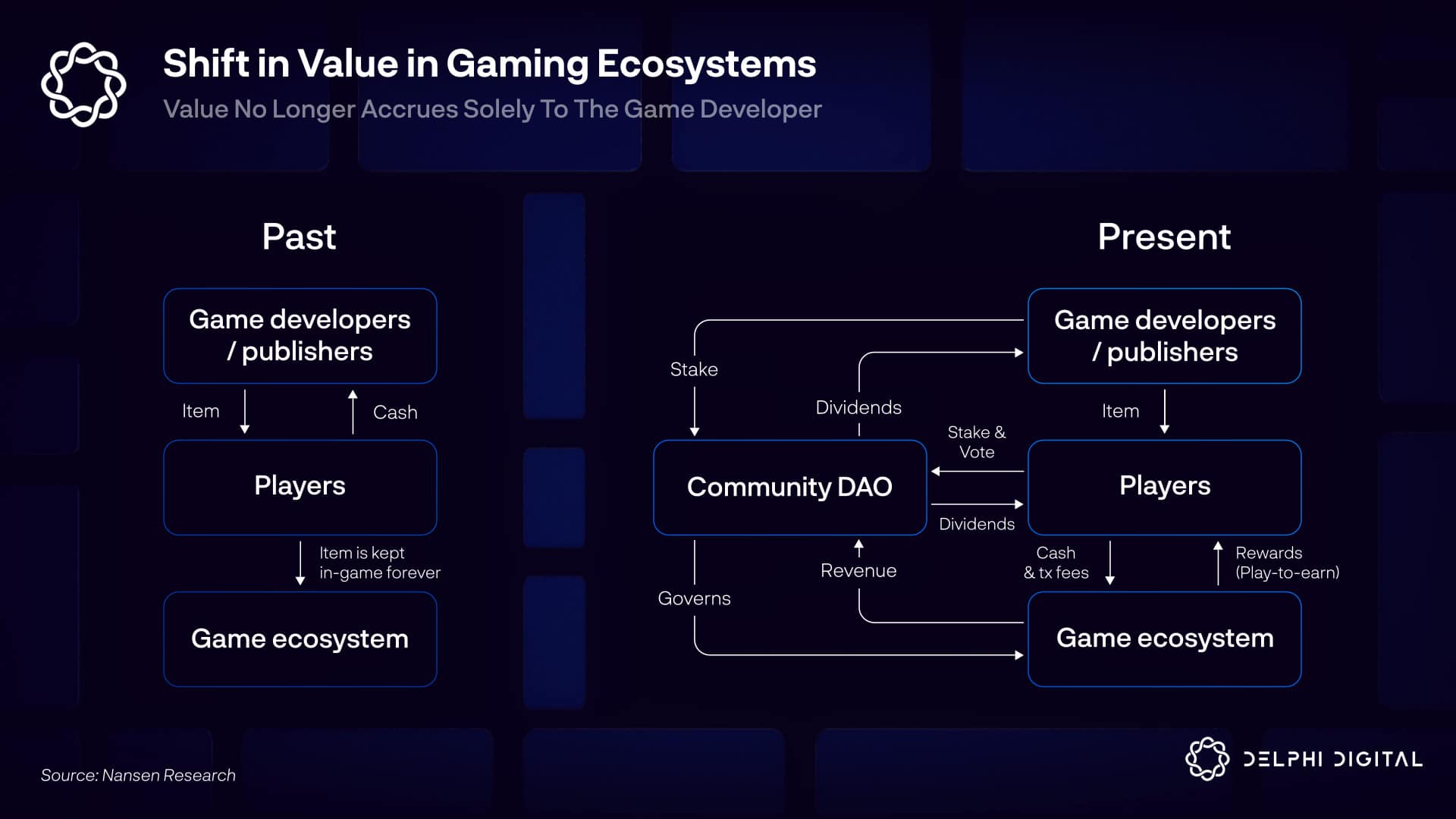

Digital property rights: In traditional games, players buying games are actually just “renting” digital items (such as skins in Fortnite) from game companies. When game assets become NFTs, there are new guarantees for players and their achievements. If the game ceases to function, other parties could theoretically step in to cash in on the utility of these assets, which otherwise may still have enduring collectible value.

Secondary Market Liquidity: True digital ownership transforms consumer psychology, creating residual value for digital purchases within a globally verifiable liquidity layer. If users wish to leave the ecosystem, they can retain value from their investment.

Provenance: Virtual goods now have a rich, verifiable history. Imagine being able to own the signature gun skins your favorite esports players use to win world championships.IlluviumCommunity Governance: Gamers can now participate in the direction of their favorite games through DAOs and councils (eg

Illuvinati Council).

Accumulation of value: As more players spend time and money in these worlds, the value created by the entire game can be transparently accumulated into the ecosystem token.

On-chain reputation: A new player-centric design space is unlocked, as players can now build strong cross-ecosystem player profiles. We'll explore some of its uses later in the PlayFi section.

Web3 payment infrastructure: By using encrypted payment rails, payments can be seamlessly implemented in many use cases, such as smart contract prize pools and tournament payments - which are especially onerous in traditional esports.

For creators and developers, the following improvements have been implemented:Increased monetization opportunities: Compared to the free-to-play model, more monetization opportunities are realized. On average, less than2% of players

In-game items will actually be purchased. The ability to realize monetization on such "long tail" users comes from a deeper willingness to spend, which is driven by the benefits to players mentioned in the previous section (eg, digital asset ownership, asset provenance, etc.). Additionally, secondary market activity that would previously have been lost to peripheral gray markets can be captured. Importantly, this should be done discreetly and in a harmless manner, which we will discuss additionally in a later section.

Enhanced economic alignment: Sharing a portion of revenue with players and creators in the gaming economy means lower acquisition costs and higher retention than traditional free-to-play games, and helps improve LTV. Users can take a place in the game world they care deeply about.

Improved Creator Economy: With UGC games like Roblox, creators only keep about 30% of revenue. With blockchain games, creators typically retain more of the value of their creations and benefit from on-chain royalties.<>Interoperability and composability: While this will take time, blockchain technology has the potential to enable cross-ecosystem interactions by leveraging existing building blocks and open-source infrastructure. we recognize the game

difficulty with game interoperability, and sees composability with the broader Web3 technology stack as a more promising innovation.

Finally, there must be the very obvious improvements that the blockchain has brought to the field of game financing. Many people may know that the existing Tencent-style monopoly in the game industry has formed an indestructible moat. Most aspiring game developers are drawn to developing games out of sheer passion, but quickly discover that the stagnation of mainstream business models and moats built by large corporations presents two options:

Use a predatory F2P mechanism to create several years of growth opportunities, and hope to solve the problem of user lifetime value > user acquisition cost.

Give up independent ideas and become a cog in the big corporate machine.

The AAA game industry is often criticized for its "toxic" work culture, where they work frantically for brutally brief periods. What's more, the entrenched F2P model, which sometimes favors value extraction, has taken the soul out of many games. Somewhere along the way, many of these people ended up losing their initial love for the game. At the same time, there is an oversupply of talent in the industry. By building an ecosystem that allows developers to establish and define shared advantages with audiences from the start, the amount and variety of capital available to them increases.

In a typical F2P space, it's not uncommon for marketing budgets to be equal to development budgets, as onerous user acquisition costs make it extremely difficult to stand out from the competition. In a crypto model, this marketing budget could be used to incentivize design to bootstrap the economy. Many of the world's best games were born in organic grassroots communities, not in the R&D labs of billion-dollar gaming giants. Just as the creator economy opened up people's world to even pursue their own interests, the same thing is happening on the game developer side.

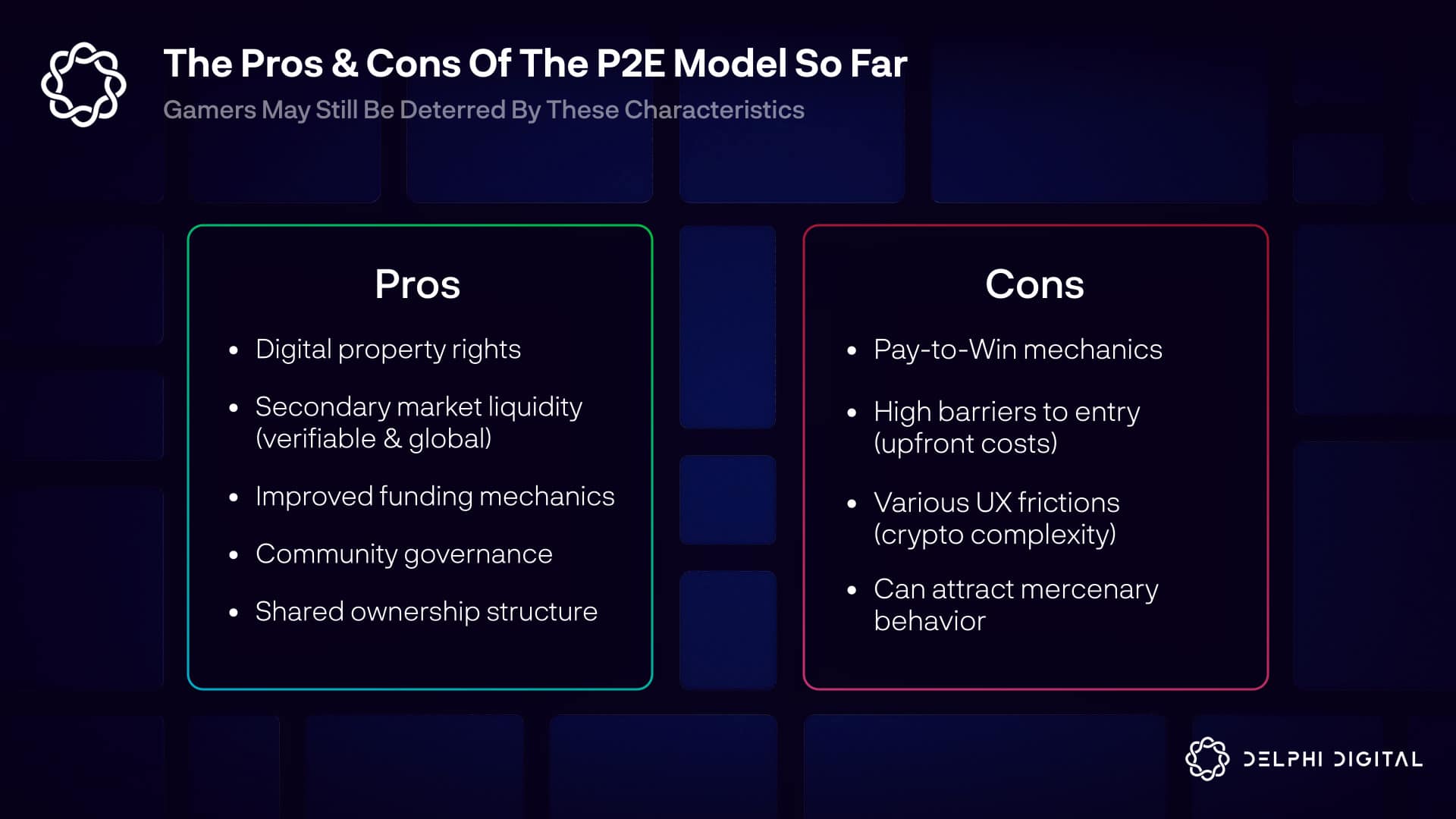

5. The current generation of crypto games

Crypto gaming took the crypto space by storm in 2021, but has lost some of its appeal as engagement has declined. Before we outline why this is the case, we should first clarify what exactly gets people so excited. Although not perfect, this mode has many advantages over traditional games. As previously mentioned, encryption unlocks digital property rights, verifiable secondary market liquidity, community governance, shared ownership structures, and significantly enhances funding options for game developers. The downside is that with the tokenization of most in-game assets, the economy becomes more difficult to manage.

This is actually the hardest early stage, which seems counterintuitive since the game's phased rollout means most of the game and the economy probably won't work properly. This tends to result in a large increase in the supply side of the economy without the necessary offsetting demand to absorb that increase. In this case, demand comes in the form of utilities for these resources. Game developers often create many levers that they can adjust to help maintain economic balance, but without the full functionality of the game, their leverage is limited.

The fluidity of all parts of the in-game economy combined with a not fully established game loop tends to cause the economy to overheat. In the beginning, the initial scarcity of all resources in the game and pure financial speculation by non-players helps keep demand and supply in sync. This dynamic creates an enticing setup for pure “mining and selling” players to enter. These players exacerbate the imbalance we discussed earlier because they join early, creating more demand for both producing and consuming assets.

As the supply of assets increases rapidly, it does not meet the appropriate levels of demand that exist in more developed economies. As prices start to pull back from the oversupply, the game's "stake-and-sell" players and purely speculative market participants also leave later. This further exacerbates the mismatch between supply and demand due to the demand destruction that occurs during the exit, leaving the economy in a situation from which it must gradually climb out.

One potential solution is to limit the transfer of expendable assets early in the game until more game and economic components are built. They won't be on-chain, just linked to the account that generated those resources. That curbs the chances of the economy overheating before it can handle that level of supply. This also moderates the price of the asset in the early days, since the game will not have a public revenue-generating asset, and its price will not be pushed up to astronomical prices by speculators for a while. The skyrocketing asset prices caused by these “mining and selling” players also ended up being a barrier to adoption for those who were genuinely interested. This non-transferability is only temporary, and at some point in the future, it can still be claimed on the chain.

Another solution is to limit the economic relevance or lifespan of these consumable in-game items or assets. By setting early on with the player the expectation that these assets will not permanently generate ROI, the player will be in a better position to manage and tune their economy. An example would be setting periodic resets for the economy (see Diablo 2's ladder, Path of Exile's seasons, etc.), resource expiration, or build lifecycles (creation, decay, and potential destruction) for assets entering the game ).

Still, introducing a currency component into the game itself has led to it tending towards the dominant motive so far. As such, the gameplay of these early games suffered in two ways: 1) the majority of the player base was primarily motivated by the expectation of financial rewards rather than the game; Spend money to make yourself successful.In 2019, Delphi helped design the AXS economic model for Axie Infinity's in-game governance token. The idea was relatively simple, but still novel at the time - to reward players for actually playing the game. That way, the gamer who spends the most time in the world will end up with stewardship, something traditional gamers openly crave. At the time, Axie Infinity had very few players, but we saw promise in Sky Mavis' ongoing project - enoughWith 473.5 ETH in 2020

quantity to purchase 5 Mystic Axies. It's worth noting that at the time no one in the community really anticipated the virality and dominance of the game's money-making dimension.

"Play-to-Earn" is also a name given in retrospect. Perhaps, given the scale of the need to make money in video games, as evidenced by the real money transaction (RMT) gray market surrounding most mainstream video games, this should be even more apparent. In the advent of the scholarship model, investors will "incubate" assets so that they can be loaned out to new entrants in exchange for a share of the income they earn, this is by accident rather than by design. Still, we eventually ran into a situation where the majority of the player base was netting, new user growth stagnated, and the in-game economy stagnated.

To further advance the lucrative nature of crypto games, we are seeing the emergence of guilds looking to professionalize and industrialize scholarship models. Pioneered by YGG, these organizations bring together users and assets to unlock economic opportunity for large populations. It’s worth emphasizing that this has had a real impact on thousands of people in countries like the Philippines, where play and earn games have literally changed the lives of many during COVID. In 2021, the association will conduct a total of US$512 million in public and private financing. Much of that money has been used to invest in in-game assets, as well as venture capital for the game itself. Because of this buying pressure wall, we've seen most fast-following games participate in this trend and seek to adapt similar mechanics.

Arguably, the industry may have started an incentive loop in game and economic design without giving enough thought to whether this is the best path. We believe that the guilds, which exist mainly to coordinate the needs of mining and selling, have strayed somewhat from their original vision, and we will discuss the way forward in a later section. Unfortunately, as is often the case with cryptocurrencies, many of the current “players” in the cryptocurrency game appear to be mercenaries. Much like yield farming, users seem to be drawn to where the incentives are strongest, rather than genuine enthusiasm for the games on offer. Not only does this result in developers essentially overpaying for early audiences, but it also hurts the real player experience. Too much emphasis on the revenue component in these early games ended up confusing organic player demand.

Having said that, we still believe that there will be huge demand for financialization games that choose to put a large portion of the economy on-chain. These games bring about a new form of play where knowledge of game skill and advanced knowledge can create alpha in the context of game economics and financially reward dedicated and savvy players. We are proud supporters of many of these games and are very excited to see the progress that games like Crypto Unicorns have made. Through a combination of economic monitoring, careful/diligent design, and ongoing real-time service development, these economies can be better calibrated and create rewarding experiences through player-driven economies.

For these financialized games, it is critical that the percentage of players who withdraw equity is smaller than the percentage of players who are happy to pay for entertainment. Ideally, "mining and selling" players provide something useful or interesting to paying players. We see first-generation crypto games as extensions of what already exists in traditional games, albeit with certain new features that make them attractive.

It is important that developers of blockchain games have a clear understanding of why and for whom they are developing. We believe that many developers have taken the decision to open up the economy too hastily, without fully appreciating the complexities involved in effectively navigating this path. To what extent have we addressed these issues? Well, it's in progress. Delphi will also continue to spend time analyzing how existing models should evolve, and looking for new models when exploring new ones.

6. Use crypto to monetize around gamesNORAnother model that the Delphi gaming team has recently explored in depth is PlayFi, developed by

first. We think this model is very suitable for esports, and Delphi will actively support projects that advance this model. To explain it better, it is worth modifying the concept of the "magic circle" in the game. Real players and free flow, free from surrounding forces vying for human attention, which is why great games stand the test of time. Games that refuse to compromise on these core principles have grace and purity. Furthermore, games that follow this pattern seem to have insulated themselves from the ephemeral nature of our contemporary digital environment.

For example, Counter-Strike remains strong as one of the greatest competitive shooters of all time, while many other games have risen and fallen around it. As we'll see, much of this can be taken from the way traditional sports work -- a model that has thrived for millennia.

In Pro Sports mode, almost without exception, the core game mechanics are very basic and easy to use. In soccer, for example, the goal is really: to kick the ball into the net. The game has certain fixed parameters; the beams have a certain height, the posts have a certain width between them, and the balls are a certain size and weight. As Brooks puts it, "The essence of any ideal game is that every throw, play, or choice acts on well-defined things—if you do it right, they're an interconnected set of behaviors."

Also, there is often very wide accessibility. No potential player can go too far in order to find a ball and a goal... Usually, the sport is easy to learn and hard to master. Players matter because difficulty is often self-directed. You can choose to practice penalty kicks, free kicks and corner kicks yourself. Introducing further challenges via satellite confrontation is just as simple - perhaps a 1-on-1 drill that gradually introduces more game rules (fouls, tackles, blocks, etc.). This can be extended to different team sizes and formats, all the way down to the most common incarnation of the beautiful game. At a certain threshold of seriousness, players may wish to invoke administrative officials enforcing the rules in more organized, competitive scenarios. At any time in football's many derivative configurations, players may wish to introduce betting, thereby raising the stakes and enhancing the competitive spirit.

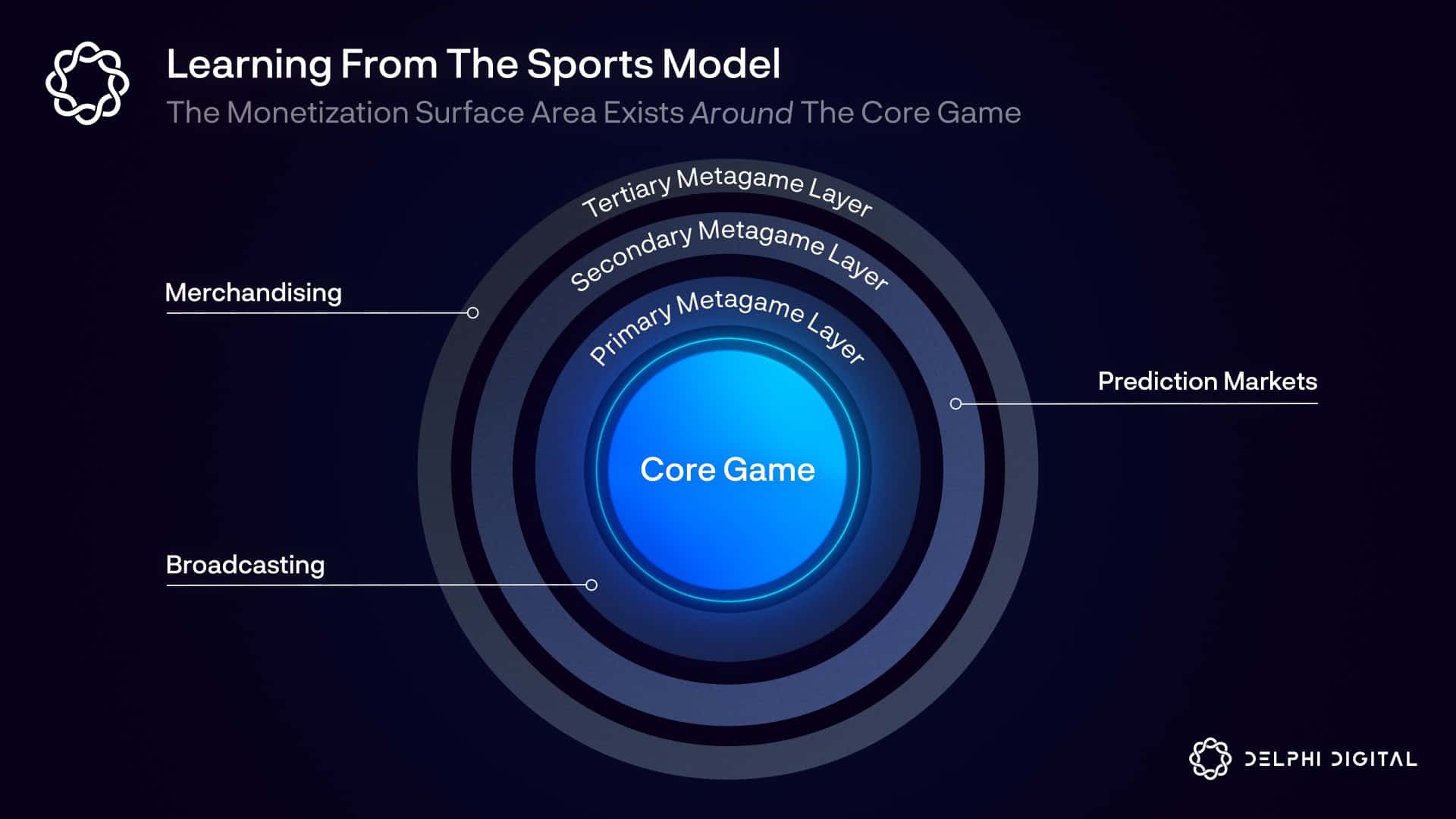

Importantly, as these scenarios become more competitive and players become more skilled, the overall difficulty rises accordingly. As the level increases, the possibility of realization also increases. These experiences are scarce. There are only so many players in the world who can compete at this level, being at the very top of a huge talent pool, so they make a lot of sense. As a result, we've seen a dramatic expansion of opportunities to engage outside of the core game in the form of coaches, fans, commentators, analysts, scouts, prediction markets, merchandise, collectibles, and more. As Brooks puts it: "This elegant correlation between increased game difficulty and increased economic opportunity/participation in games is at the root of the professional sports model, and at the root of PlayFi."

Essentially, we can think of the monetization model in sports as being entirely revolving around the metagame. These metagames behave much like derivatives of purely skill-based games. Metadata can be thought of as data that describes other data. By extension, a metagame can be thought of as a derivative game that either describes the core game or is rooted in the core game. It is important that the market game remains distinct from the core competition loop.

At its core, football is not a game of markets - it is a game of skill on the pitch. Its path to profitability starts with people caring about the sport itself, then taking metadata from the games that make the most sense and using that to play the metagame.

In the context of video games, after acknowledging that the core "magic circle" of the game must remain intact, one might wonder how we can accommodate more players who may not have a strong interest in reaching the top echelon of the game. After all, there are countless user archetypes in modern games, from whales with a desire to spend, to speculators who want to bet on top gamers, to more casual enthusiasts who enjoy games in other ways. As we explored at the end of Part 1, if the pay-to-win mechanics are not tamed, money will always gravitate toward the dominant motive. So the first stop is to separate the marketplace game from the core game loop itself. In this way, we can begin to define independent magic circles that coordinate with each other but do not interfere with each other. No one is ever tricked into playing a game they don't own.

As with the professional sports model, the scarcity of experience is also important. Both in terms of skill level and pace of play. In football, Ronaldo only sets foot on the pitch once a week. Limiting the frequency of these competing situations further facilitates their sense-making. For NOR, PlayFi's pioneering implementation, scarcity of experience, and real risk are driven by one-game tournaments. In these games, the players themselves are NFTs that are permanently destroyed if they lose. They fully own their data and metadata and directly benefit from its use in the economy around the core game. The goal of the PlayFi model is to encourage users outside of core competitors to play meta games with meta data.

In theory, the more people care about games, the more money will be spent directly on metagames. By maximizing meaning generation and competition within the core game, we are able to maximize revenue through peripheral monetization around it. Additionally, we retain the distribution advantages of the free-to-play model, since players can play for free, we can effectively price-differentiate those willing to spend more on the meta-game, while also avoiding the downside of pay-to-win.

At the heart of the framework is skill-based competition, which requires a tournament system to function. NFT is the underlying technology that allows us to tokenize any unique digital item - including tournament entries that serve as tickets. For example, let's look at the stand below, which has a total of 8 entry-level slots. Each of these starting points can be sold in a primary auction and then freely traded on the secondary market without affecting the core gameplay. Smart contracts representing prize pools could account for up to 50% of all revenue generated (excluding sponsors), further increasing the appeal of the competition.

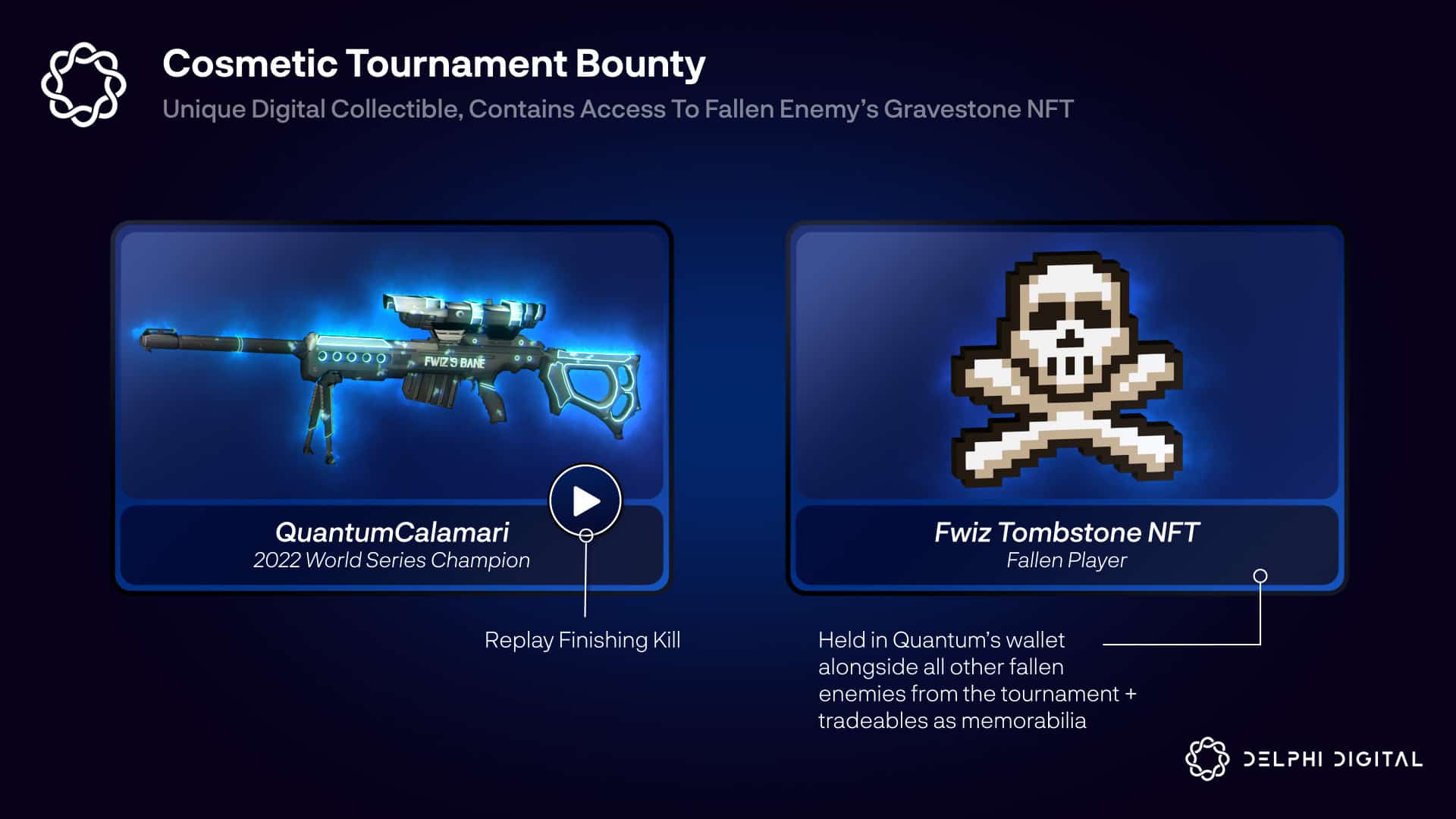

While some of this may sound similar to some modern esports, it's hard to overstate the significant advancements that Web3 has brought about. Ultimately, cryptocurrencies will primarily be used as a backend accounting engine, facilitating ticketing, payments, player NFT contracts (on-chain reputation), automated tournament bounty smart contracts, and more. Cryptocurrencies unlock new levels of transparency in player profiles, deep liquidity layers that facilitate seamless payments, and new ways for people to place bets without navigating through burdensome infrastructure. Furthermore, many properties of encryption technologies such as digital origins open up a new way of thinking about the digital realm. How much would you pay for Ali's boxing gloves? And now, how much would you pay for a skin for an esports tournament you care so much about?

We now have rich digital experiences where fans can collect items from meaningful moments in esports history. The exciting thing about building this in crypto is being able to unlock open source infrastructure that can be used for many applications across the industry. All esports-style games should be able to plug into the same set of standards, and Delphi hopes to contribute to some of them. Once all the data, metadata, and infrastructure is consolidated into one place, we can let third parties come in and develop their own metagames around those games.

It's hard to imagine that this will lead to many more popular downstream applications, but we're excited to see what emerging behaviors and gameplay can be unleashed. Once the technical foundation is laid, we believe that users will, as always, drive creativity in their respective ecosystems. Finding the best meta games for professional sports takes time, and we hope the same will be true for PlayFi.

In the case of "earn while playing" games, the tokenization of game assets 1) increases startup costs (friction) because players need NFTs to play games; 2) because in-game assets are NFTs with secondary market liquidity , The money-making mechanism has also gradually weakened the competitive game. Using the PlayFi model, the first change is that users are not required to own NFTs to play games. In other words, make it play like any other regular video game. Importantly, this does not mean that NFTs cannot and will not exist.

As we mentioned before, scarce, unique digital assets still have their uses, but how these assets enter the game matters. For example, I might still be rewarded with digital collectibles, but that should make sense to me in the context of the game. Additionally, we are able to alleviate many of the distribution frictions associated with crypto games in traditional app stores, since all monetization can happen outside of the game.

The interesting thing about these components is that they don't necessarily conflict with the current generation of P2E games and guilds. In fact, the existence of these primitive factors can be used to enhance this generation of P2E games instead. For example, a game like Axie could have a skill-only free-to-play mini-game mode where NFTs are awarded to tournament winners as true badges of honor. This will also reduce the friction for new players to adopt.

Guilds like YGG can continue to grow their businesses, and besides providing player liquidity to bootstrap new gaming ecosystems, can now leverage player NFT profiles to attract talent to their guilds, just like traditional esports teams . Guilds can then allow players to participate in tournaments to win prize pools, earning money for their efforts.

While unproven, we believe PlayFi has what it takes to propel esports into a golden age and unlock its true potential as a global entertainment powerhouse. We will actively support projects such as NOR that develop infrastructure in this field.

7. Conclusion

The past year-plus has been indelible for crypto gaming, and despite all the growing pains, we're more excited than ever to be a part of it. We must also emphasize again that this field is still in its early stages, so it is difficult to determine which models will win over time. As supporters of the field, Delphi regularly challenges the assumptions we make and tries to map out novel ways these technologies can improve games for players and developers.

We think this is a good time for developers looking at this space to think about the complexities involved in opening up economies, and the extent to which these games contribute to over-financialization. We hope the path paved by PlayFi will lead to some further ideas on how crypto can improve gaming and monetization. The only way we're going to reverse mainstream perception is by building experiences that demonstrate the power of this technology. thereby improving the experience.

Importantly, we believe that there are many other models that are particularly suitable for crypto games, which we have not explored in depth here. For example, a UGC-focused platform is well suited to incorporate encryption. The ability to program royalties from derivative creations from third-party developers is very promising. In such a world, things can become granular enough to allow the designer who created a particular asset to participate in the economics of its use in multiple worlds. We're particularly encouraged in this space by projects like Webaverse, which builds an open-source game engine that's entirely browser-based.