Understanding MEV2.0: How can users become MEV beneficiaries?

Original title: "MEV2.0: MPSV breaks the oligopoly of the MEV market and makes users passively profitable"

Original compilation: Skypiea

Original compilation: Skypiea

Since 2017, Maximum Extractable Value or "MEV" has undergone several major innovations. These advancements revolve around two actors, miners and MEV seekers. One of the biggest leaps forward in the MEV space was the creation of Flashbots to democratize MEV for these two players. However, with the existence of MEV today, a key player is still neglected: the user. While this is widely accepted today by Ethereum’s Proof of Work (“PoW”) consensus mechanism, Proof of Stake (“PoS”) opens the door to redefining MEV to potentially include users. Most of today's MEV solutions focus on miners, MEV searchers and even builders. We believe users can and should be included in the mix as well.

This paper introduces the concept of MPSV (MEV Profit Sharing Validator), a novel concept that can make users as beneficiaries of MEV, which will eventually complete the full democratization of MEV. By fully democratized, I mean users may end up getting a portion of MEV profits because they "choose" where to stake. However, before we get into MPSV, we first need to understand: (1) advanced MEV players today, (2) the economic market structure of MEV, (3) proof-of-stake (PoS) systems in general and the role of validators, and Finally (4) some game theory.

MEV participants

Maximum Extractable Value (MEV) remains one of the areas in the crypto market where participants can extract profits, be it a bull or a bear market. MEV refers to extracting value from users by reordering, inserting, and censoring transactions within blocks.

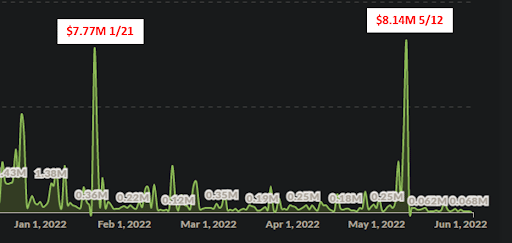

image description

Source: explore.flashbots.net

* Gross profit = daily value extracted from successful MEV transactions without removing miner payments

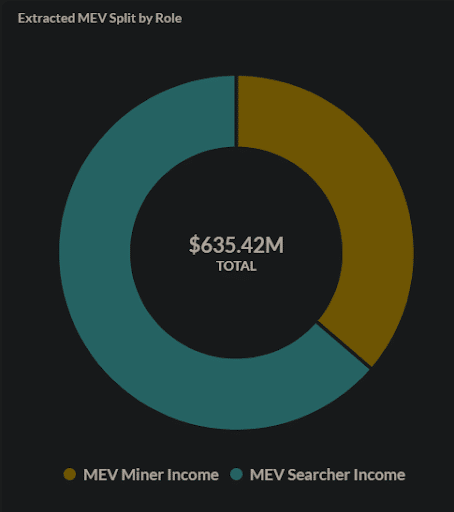

image description

Source: explore.flashbots.net

Economic Market Structure and MEV

Before analyzing market dynamics, it is important to clearly define its structure. Let's first look at the overall structure of the MEV market, followed by the sub-markets of MEV Seekers and Miners.

MEV market

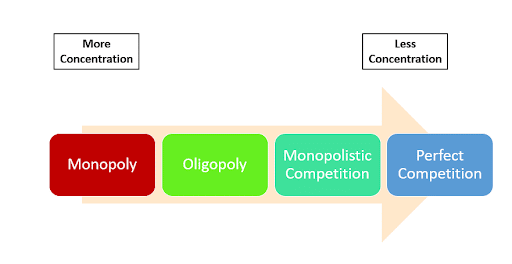

The MEV market is unique in that there are two players, miners and MEV seekers, who work together to extract value. When assessed as a whole, the entire MEV market is more like an oligopoly structure.

An oligopoly is a market or industry dominated by a small number of large sellers or producers, in this case block space is a commodity produced and monetized through MEV. Let's see how an oligopoly translates into today's MEV market:

1. High barriers to entry:

Miners: High upfront costs of equipment, technical expertise and capital requirements make market entry extremely difficult for individuals

MEV Seekers: While this may not be capital intensive, the high barrier to entry comes from the technical skills, specialization, and deep understanding of DeFi, ETH, and other blockchains required to run an MEV strategy.

2. Imperfect competition/pricing power:

Typically, MEV Seekers and Miners will work together to maximize total extractable value, even if it comes at a cost to users. Additionally, miners have an advantage because they can choose to accept any MEV Seeker who offers the highest reward — making these miners price makers.

3. Enterprise interdependence:

Due to their large size and minimal competition, how miners build MEVs affects the actions of other miners.

Additionally, MEV Seekers and Miners are interdependent, as Seekers are the ones who seek out MEV opportunities and submit those opportunities to Miners to decide whether to reorder, insert, and/or censor transactions within a block.

4. Non-price competition:

In general, miners compete not for profit sharing between MEV Seekers and miners, but on other factors: specialized equipment, hosting, service level, and brand.

5. Possibility of collusion:

Given the centralization of miners, they can actually work together in this space as well. There may be an agreement among miners that they will only accept to share 95% of MEV profits with searchers. However, Flashbots solves this problem in the current MEV market.

Likewise, if MEV Seekers band together, they may demand a higher profit split between miners and MEV Seekers.

MEV Seeker Marketplace

Now that we have defined the overall MEV market, we can also look at its submarkets. Now let's look at the MEV Seeker Market.

MEV Seekers are like the “plumbers” of the blockchain. They dig into the transactions within a block to find MEV. It is a group of artisans and professional anonymizers who possess valuable technical knowledge on how to extract value. This dynamic is characteristic of monopolistic competition.

Monopolistic competition (not to be confused with monopoly) is a type of imperfect competition where there are many producers competing against each other but selling services that differ from each other rather than being perfect substitutes.

Let's see how monopolistic competition characteristics align with the MEV searcher market:

1. Slightly different services:

MEV Seekers are all trying to find extractable value on-chain, although MEV's approach varies by Seeker. For example, a searcher may specialize in arbitrage, liquidation, sandwich strategies, or specialized long-tail strategies.

2. Many searchers:

self-explanatory

3. Maximize profit:

MEV Seekers seek to maximize profits and thus extract as much MEV as possible from the block. Similar to a pure game monopoly, each searcher will try to find as many MEVs as possible without being penalized by users (usually).

4. Incomplete information:

MEV searchers have an information advantage over users, and users often unknowingly give up value to searchers.

5. Results:

Searchers know their actions won't affect the actions of other searchers.

MEV mining machine market

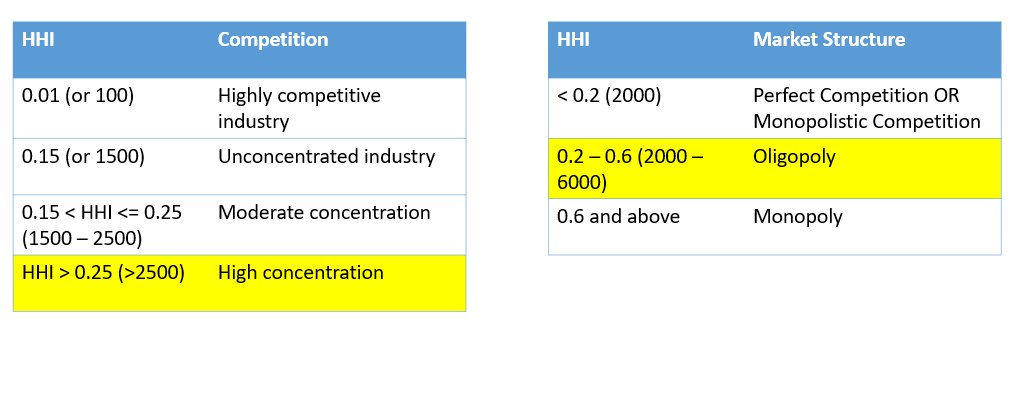

One of the core reasons why the MEV market resembles an oligopoly is that the miner market is oligopolistic. Whereas MEV Seekers cooperate with miners - these two markets combined are more like oligopoly vs. monopolistic competition. In this section, instead of revisiting the characteristics of an oligopoly, we can calculate the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) to understand the concentration of the miner market.

The HHI index is a measure of the size of companies in relation to their industry, as well as the degree of competition among them. Calculated as follows:

In this equation, MSi is the market share of firm i and N is the total number of firms. We add numbers to understand the concentration of the industry. We square MSi because squaring all weights gives larger weights to players with larger market shares.

We can use MiningPoolStats to get an idea of each miner's hashrate, which is ultimately a benchmark for their market share (about 81 miners listed). We use the following steps:

Convert each miner's computing power to TH/s

Total computing power TH/s

Divide the computing power of each miner by the total computing power

Square each value in #3

Summary #4 Total

If we calculate the HHI of these miners, we get a HHI of about 545 or 0.545, which means that the miner market is highly centralized and belongs to an oligopoly market structure.

Optimal Perfectly Competitive MEV Market

Perfect competition is an ideal market structure in which all producers and consumers have sufficient and symmetrical information and there are no transaction costs.

The characteristics of a perfectly competitive market are:

large number of buyers and sellers

Product homogeneity

Free entry and exit of enterprises

Sound market knowledge

Sellers earn normal profits (as opposed to extraordinary profits)

In this market, we have reached the point where the quantity supplied is equal to the quantity demanded, hence Pareto Efficiency. Pareto efficiency is a situation in which no individual or preference criterion can be made better without making at least one individual or preference criterion worse.

One of the greatest innovations in the MEV space was the creation of Flashbots to democratize MEV.

“Mitigating the negative externalities of current maximum extractable value (MEV from now on) extraction techniques and avoiding the existential risks that MEV can pose to state-rich blockchains like Ethereum.”

The 3 goals of Flashbots:

Democratize access to MEV revenue

Bringing Transparency to MEV Activities

Redistribute MEV revenue

Flashbots help level the playing field for MEV seekers by helping prevent collusion and democratize MEV. While Flashbots have democratized MEV opportunities for searchers, users are still left out. One could argue that anyone can participate in MEV, including users, however, we know this is not realistic as most DeFi users do not have access to MEV.

So while MEV Seekers and Miners get better out of Flashbot's MEV system in a proof-of-work system, users either get nothing or are targeted for extractable value. The MEV dynamics of today's searchers and miners are not enough to fully democratize MEV and push it into a fully competitive market. Proof-of-stake, however, could change this and eventually bring us to a theoretically perfectly competitive market.

A New Paradigm: Entering Proof-of-Stake

It’s no secret that Ethereum is moving to a proof-of-stake (PoS) system. In PoS, instead of miners competing with each other to verify and confirm transactions, "validators" are randomly selected to verify transactions according to the leader's schedule.

Proof of Stake (PoS) is a cryptocurrency consensus mechanism that requires you to stake or set aside coins to be chosen at random as validators.

What fundamentally breaks oligopolistic competition in Proof-of-Stake is that users are able to decide which validators to stake assets with, which may affect leader selection or stake weighting (more on this below).

We may be able to learn some lessons from Solana on how users can potentially participate in the yield of MEV and benefit from "extractable value". The game changer for users in Proof of Stake is where they decide to stake their tokens, which opens the door for MEV innovation. The greater the stake weight of a validator - the higher the chance of being elected as a leader.

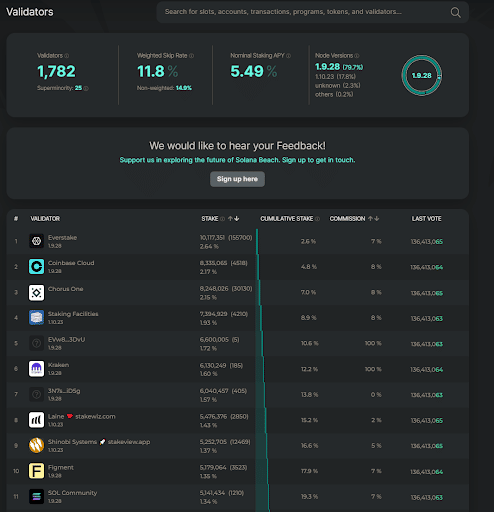

Before starting to understand how it helps to know some basic information about validators on Solana.

Solana Consensus and Validators

Solana uses Proof of History, its own novel Proof of Stake consensus mechanism. Solana's network infrastructure consists of validators and RPC nodes. Validators are the backbone of the Solana network and are responsible for processing transactions and participating in consensus. Validators are the "consensus nodes" of the network, which means they validate transactions, vote on blocks, and drive the consensus mechanism of the Solana network. Running a validator (or RPC node) requires a dedicated bare-metal server with high-end specs.

From Solana's documentation on the leader scheduling generation algorithm (note #3):

Leader (Leader) plan generation algorithm

Leader plans are generated using a predefined seed. The process is as follows:

The PoH tick height (a monotonically increasing counter) is used periodically to seed a stable pseudo-random algorithm.

At that height, banks are sampled for all collateralized accounts that have leader status and vote within the cluster-configured number of ticks. This sample is called the active set.

Sort activity sets by stake weight.

A random seed is used to select stake-weighted nodes to create a stake-weighted ordering.

This ordering takes effect after the number of ticks configured by the cluster.

Today, validator rewards are divided into 3 categories:

Protocol-Based Rewards: Issued at an inflation rate defined by a global agreement - Rewards are provided on top of earned transaction fees.

Staking: Stakers are rewarded for helping validate the ledger. Users benefit from staking because they can delegate their stake to validators. Validators are responsible for replaying the ledger and sending votes to each node’s voting account, to which stakers can delegate their stake. When a fork occurs, the rest of the cluster uses these stake-weighted votes to select a block.

Staking Pools - These are liquid staking solutions that help facilitate censorship resistance and decentralization, such as Marinade Finance and Lido.

Today's staking yield is based on the current inflation rate, total SOL staked, and individual validator uptime and commissions. The validator's commission is a percentage fee paid to validators by network inflation. Validator uptime is determined by validator votes.

In other words, staking rewards come from Solana's inflation plan. Validators provide users with staking rewards, but validators may also charge users fees/commissions. What if we could increase rewards beyond standard inflation in a way that benefits everyone?

Users can stake with their preferred validator and switch to another validator if they wish, which takes 2-4 days on Solana. Additionally, with solutions like Marinade's Liquid mSOL, users can instantly unseal mSOL tokens for SOL in real-time. This creates an interesting competitive dynamic among validators. Users will choose the validator who gives them the highest rewards and the validator who charges the lowest fees/commissions.

When other conditions remain unchanged, the user will choose the validator with the highest return rate and the lowest fee.

This is where things get really interesting! The more SOL a validator is able to pool and stake, the higher the stake weight the Validator can obtain. The greater the stake weight of the Validator, the greater the chance of becoming a Leader. Think of it like a lottery system, where the more stake a validator has, the better the chance of being elected as a leader.

MEV on Solana today

Today, the majority of MEV extracted on Solana goes to MEV Seekers. Most of the MEV on Solana comes from bots spamming the Solana blockchain, constantly trying to find arbitrage opportunities or to pre-empt NFTs. Since transaction costs are so cheap on Solana, running a bot is an easy strategy to capture MEV opportunities.

Future MEVs on Solana

Now, one way to break the cycle of these spam bots is to set up a sealed bid state auction, so that disputed resources are more expensive than others to get locked. On Solana, Jito Labs is building a sealed silent bidding auction to enable seekers to bid on block space. The benefits of this include the ability to have MEV transactions run off-chain in some sort of public mempool (Solana does not currently have one). Transactions sent via Jito will be prioritized and rewards shared with validators, similar to Flashbots. The benefits of doing this include:

Kill spam bots - they can no longer find meaningful MEVs because they are not priority transactions

better user experience

Help unblock the Solana network and make it run more efficiently

So how can we fully democratize MEV and push it into a fully competitive market?

User Choices!

Enter MPSV, the future of high-efficiency MEV market

Some interesting game theory arises when MEV Seekers are able to cooperate with Verifiers to extract MEV. An optimal outcome would be for users to eventually be able to passively earn a portion of MEV rewards, but how?

MPSV = MEV Profit Sharing Validator

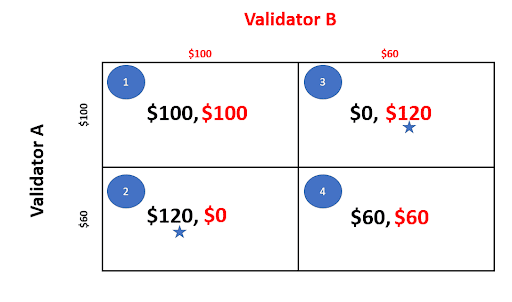

Let's first explore two game theory exercises. Game 1 is trivial, but let's take a look at it. Should validators and MEV Seekers share rewards? For simplicity, let us assume: there is only one MEV searcher and one validator.

As I mentioned, this case is trivial because neither party would agree to work together if neither party wanted to share any type of reward and wanted to keep 100% of MEV withdrawn. The optimal solution in the diagram above is to split the profits between MEV Seekers and Validators. While 50% is somewhat arbitrary, it's in everyone's best interest to work together. It doesn't matter whether it's 60/40, 90/10, etc. - they have to work together.

It is clear that there is an interdependence between MEV Seekers and Validators of the MEV marketplace. Cannot exist without the other.

In the long run, we may see a world where validators bring MEV Seekers inside or start running MEV strategies themselves - leaving only exotic forms of MEV available to Seekers.

The next case is a bit more interesting. We have established above that there will be some profit sharing between validators and MEV searchers. Now we ask, should validators themselves decide to share any MEV profits with users staking on their platform?

Let's assume the following:

The interdependence of MEV searchers and verifiers has been established according to Game 1.

There are now two validators: validator A and validator B

Both start with the same amount of staking weight (i.e. same amount of staked assets)

Users are economically rational, i.e. users will choose to stake with the validator who offers the highest reward

Validator A and Validator B each decide how much MEV profit they want to share with their respective users

If a validator loses its users, it can no longer become a leader (assuming all its tokens have been transferred to another validator)

If a validator loses its users, it no longer receives any MEV transactions from Seekers, but transfers MEV transactions to another validator

Assuming the resulting MEV is uniform and constant, i.e. each validator has an MEV of $100, the numbers outside the box represent how much profit each validator decides to keep.

We assume long-term situations, not short-term ones.

Now let's look at each scene in each box.

1. A = B。

Validator A sets its MEV profit to $100 (User A profit = $0).

Validator B sets its MEV profit to $100 (User B profit = $0).

User total profit = $0.

The two validators each take home $100, and the user receives nothing.

2. A < B。

Validator A sets its MEV profit to $60 (user profit = $40).

Validator B sets its profit to $100 (user profit = $0).

Users earn $40 per MEV transaction ($80 in total).

In the long run, validator B's users leave, and validator B ends up with $0 in profit.

Meanwhile, validator A gets an additional MEV transaction and earns an additional $60 ($60 + $60 = $120). The logic is as follows:

long run

Again, users are rational because validator A offers higher staking rewards - users transfer funds to validator A and abandon validator B over time.

Because users transfer all their staked assets to validator A, validator B no longer has the opportunity to become a leader and no longer receive MEV transactions from seekers.

* should flow to validator A for the MEV generated by validator B - providing the same level of profit, i.e. $60 + $60 = $120.

This ultimately pushes Validator B's MEV profit to $0.

3. A > B。

The logic in #2 above applies.

4. A = B。

Validator A sets its MEV profit to $60 (User A profit = $40)

Validator B sets its profit to $60 (User B profit = $40)

Users earn $40 per MEV transaction ($80 in total).

In this case, users from A stay where they are, and users from B stay where they are. No validators are relinquished.

MPSV Nash Equilibrium

A Nash equilibrium is a decision theorem in game theory that states that players can achieve a desired outcome by not deviating from their initial strategy. In a Nash equilibrium, each player's strategy is optimal when considering the decisions of other players.

From the diagram above we can see that if both validator A and validator B set the profit equal to each other, they will both do better than setting the profit at a higher level (ie box 1 instead of box 4). But the question remains, is Box 1 the result we can expect? To fix this, let's first find the responses from validator A and validator B:

Similar to above, let's step through each response starting with validator A:

A. For validator A, if validator B sets her profit to be $100, then validator A has two profit options (box 1 and box 2):

$100 if validator A sets profit to $100

If validator A sets a profit of $60, it will be $120

Given that validator A is economically sound - it sets the profit at $60, this would yield a total profit of $120.

B. For validator A, if validator B sets her profit to be $60, then validator A has two profit options (boxes 3 and 4):

$0 if validator A sets profit to $100

$60 if validator A sets profit to $60

Given that validator A is economically sound - it sets the profit at $60, this would yield a total profit of $60.

Note that setting the profit at $60 instead of $100 is validator A's dominant strategy in both cases above. Validator A setting a profit of $100 is never the best response.

Verifier B:

C. Boxes 1 and 3:

Given that validator B is economically sound - it sets the profit at $60, this would yield a total profit of $120.

D. Boxes 2 and 4:

Given that validator B is economically sound - it sets the profit at $60, this would yield a total profit of $60.

Nash Equilibrium: For validator A and validator B, there is only one potential outcome where both validators respond optimally, and that is if both validators set their profit at $60 (yellow box in the diagram above ). This would be the only Nash equilibrium where they would each have a total profit of $60.

Thus, we have shown above that if users are able to transfer their staked assets fluidly between validators, then a Nash equilibrium occurs when validators offer the most attractive profit-sharing allocations that benefit users, something like How it works in a perfectly competitive market:

This is what produces the MPSV = MEV Profit Sharing Validator.

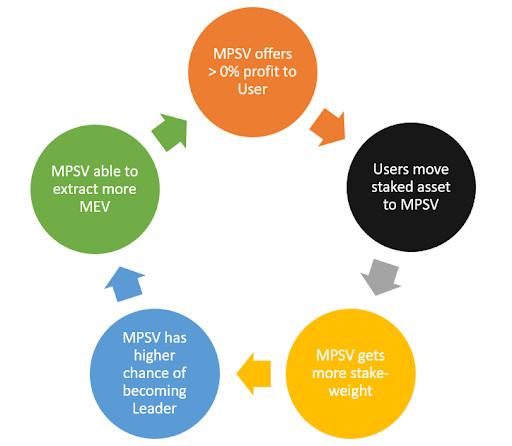

MPSV flywheel

Proof of Stake (PoS) enables users to decide where they want to stake their assets. With other conditions unchanged, having more staking weight can make you a leader in the PoS model as a validator. For a rational economic player, deciding where to bet depends on where you can earn the highest APY with the lowest fees/commissions.

in conclusion

in conclusion

Summing it all up, we can see that there is a proof-of-stake MEV scenario where everyone is actually better off, including users. In a proof-of-work system - miners act independently of users when confirming blocks. In a proof-of-stake system, there is a dependency between validators and users.

This is what I mean by "fully democratize MEV". We have shown above that the Nash equilibrium of MPSV occurs when different validators share the most attractive profits with users. In the long run, only one validator can provide users with a better share of MEV profits, thereby driving the validator market.

We believe MPSV can play the following roles:

Create new transformations in MEV, users can passively benefit from MEV

For smaller MPSVs, if they can share more profits with users than the top 10 or largest validators, this can be used as a way to compete with larger validators - even with other small MPSVs Join forces and share MEV profits.

In a highly competitive scenario where all validators pass 100% of the MEV profit share to users, users end up benefiting overall. [Note: Validators can still earn income through transactions and priority fees].

Everyone is better off in this world, including MEV searchers, validators, and users in this model.

What breaks the oligopoly in the MEV market is user choice!

Maybe, just maybe, we'll transform the MEV market into a perfectly competitive market structure.