W&M Report (1): Will music NFTs have their PFP moment?

Original Author: Water & Music

This article is from The SeeDAO.

This article is from The SeeDAO.

TL;DR

first level title

first level title

text

text

As Marshall McLuhan said "the medium is the message", this is perhaps one of the most compelling themes in the history of media and technology. That is, the way people express themselves—and, conversely, the way that expression is perceived by others—is shaped by the medium of expression.

For better or worse, this dynamic has defined every step in the evolution of the mainstream music industry in the past. A big reason why, even in the streaming age, commercially released albums still typically last 40 to 50 minutes is that a 12-inch 33-rpm vinyl record can hold about 22 minutes of music per side, for a total of about 45 minutes. Likewise, songwriters now routinely adjust the structure of their songs to fit Spotify's playlist algorithm. For example, moving the hook of the song (the most hooked part of the song) forward, reduces the chance of being skipped by the algorithm, so as not to fall behind in the Spotify playlist sorting. More recently, the viral power of short-video apps like TikTok has further cemented this mindset in the industry, making the 15-second earworm a staple unit of music creation. In all these cases, the distribution channel had a direct impact on the creative plan.If it is indeed true that the medium is the message, thenWhat is Web3's unique musical language?

In other words, what types of creative processes does blockchain technology uniquely encourage and enable? What can we expect from the encrypted version of the 15 second hook?

Perhaps the most visible examples of Web3-native creativity today come from the visual world. From CryptoKitties and CryptoPunks in 2017 to Bored Ape Yacht Club and SquiggleDAO in 2021, these financially successful NFT projects all stem from a common creative template - using code to generate hundreds of thousands of unique pieces of art Artworks, which all have a basic visual identity and varying degrees of rarity, can be verified and monetized on-chain. On social networks, people generally refer to these projects as "PFP" ("picture for proof" picture proof, or "profile picture" profile picture), because using these NFTs on social media can show that they belong to a specific , a unique group of collectors. These projects are usually generative, relying on code (on-chain or off-chain) to create a large number of visual digital assets in a short period of time, rather than having specific artists to hand-craft each digital asset.Slowly but surely, we are seeing a similar mindset among musicians, leveraging Web3 to experiment with large-scale, distributed music and audio creation. The Water & Music community has identified theNearly 30 music-themed generated/PFP NFT items

- From Holly Herndon's groundbreaking Holly+ speech synthesis project; to one-shot generation of collections of audiovisual NFTs such as Invocation (Telefon Tel Aviv x EFFIXX) and Rituals (Justin Boreta x Aaron Penne); to more standard PFP-type projects such as 6ix9ine's TROLLz and Trippie Redd's Trippie Headz. (Water & Music members can go to the Music/Encrypted Data Dashboard to access the full list of generated/PFP music projects in a new, members-only tab.)

What makes these generative/PFP music projects particularly exciting is not only that they advance the intertwining of fandom and creativity, bringing to the masses previously fringe or niche ideas that previously revolved around crowdsourced creative and distributed brand assets, but also Because Web3 has the potential to drive these creative projects to find dynamic, innovative and sustainable business models that would otherwise not be economically sustainable.That is, the reality is that,The social and financial value generated/PFP music NFT series have not reached the same level of sustained success as their visual counterparts.

It may come as a surprise to say this: music has benefited directly from the Web3 wave in other ways (mainly through one-off NFT releases), and music is increasingly visual in modern expression and no longer an inherent cultural and social forms of art.The core question we want to explore in this paper,Not only the trends of Web3 native music PFP projects so far this year, but also the challenges of scaling these projects to the masses.Through our market research and interviews with several founders of the music-generating NFT project, we found that bridging this market gap is by no means as simple as copying and pasting routine operations from the visual world to the music world. In fact, it may require a rethinking of the entire traditional music industry notions of celebrity, intellectual property, and fan engagement.

While all the technology to enable generative/PFP music NFTs exists, the social, cultural, and legal foundations arguably don't yet exist.

We explore this argument by addressing the following questions in turn:

More historical background on generative music creation, why it matters for music, and why it makes sense for generative music artists to adopt Web3.

An in-depth look at the social, cultural, and legal challenges faced by generative music NFT projects, and the unique opportunities for experimentation these challenges offer artists.

first level title

Creative Background: Generative music composer as a "gardener"Renowned artist and producer Brian Eno coined the term "generative music" in the 1990s to describe a systems-based music-making paradigm in which a composer builds some kind of automaton (i.e., a pre-programmed self-operating system) that Self-generated music, rather than humans directly using sound to create a discrete composition. Eno drew inspiration from contemporary scientific thought of the time, including cybernetics, nonlinear systems theory, and chaos theory—where the key consensus was that,Even the simplest systems can generate complex behavior.

A set of rules, if tuned just right, can have profound and unforeseen creative potential.

Inspired by these ideas, Eno reported a fundamental shift in his thinking in the early 1970s, from an "architect" to a "gardener" in his understanding of music composers. As he shared in a 2011 interview, it's "a shift in the idea of the composer: from being someone at the top of the process and dictating exactly how it goes, to being at the bottom of the process, carefully picking, carefully Someone who nurtures them and wants them to grow into something.” In other words, under this new paradigm, the composer’s job is simply to provide the material for the composition, not the finished product, not even a clear set of instructions.

Importantly, you don't have to use a computer to generate music. Eno's breakthrough ambient album, Discreet Music, used asynchronous tape loops to let pre-recorded material create endlessly novel combinations; Steve Reich used a similar approach on It's Gonna Rain to stunning effect. But computers are clearly the ideal medium for designing generative automata, and as any programmer will tell you, the fruits of programming are all about abstraction, and making music by creating a system that makes music is just a higher level It's just abstract. More recently, apps like Endel, Boomi, and Jean-Michel Jarre's EōN have attempted to bring these computerized generated and adaptive musical experiences to more mainstream fans, often raising millions of dollars at risk in the process. capital funds.

In the Web3 community, the term "generate" is widely used for artistic projects, which commonly use code to produce a large number of unique objects on the blockchain. Probably the simplest form of "generated" blockchain artwork is PFP-forward, which mixes and matches different features onto a cartoon avatar, like BAYC. But in these cases, the algorithm simply compiled a limited combination of prefabricated elements, which could not meet the original definition of "generated" by artists like Eno. On the other hand, portfolios like deafbeef and Tyler Hobbs' Fidenzas, the pieces and the codes that create them are all considered astonishing works of art.

Making creatively generated music more accessible and acceptable to a more mainstream audience remains a challenge. First, even on-chain creative code is often rendered through the browser by off-chain code libraries such as p5.js for Audioglyphs and Art Blocks. And the audio output from these libraries will still sound rough compared to the high-quality studio work fans are used to consuming, so don't even think about getting paid for it.Nevertheless, in the context of blockchain and NFT,As long as collectors want more unique pieces and creators don't have the time to handcraft them, generative creations will continue to fill the void.

As a potential distribution layer on top of the generative music experience, Web3 is particularly compelling because it can make both the concrete musical output and the formula behind it collectible—since in most of these projects, the underlying generative Both the logic/script and the final result are stored on-chain. This dovetails with the primary collectible motivation of most generative NFT projects. If an on-chain artwork has the code needed to render it, it will feel more durable.

first level title

Basic Mechanics of Generating Music NFTs: Rarity, Blind Box Minting, and Burning

In some generative music NFT projects, if the goal is to reproduce the financial success of visual type projects, let's analyze which features and elements of visual PFP projects can be well used in music projects.On a technical level, many of these uses are reasonable and are already being done. For example, a common element in visual PFP projects is to assign different visual or character elements (such as clothing, hair color) a relativerarity

, these elements may be incorporated into the final work of art. Rarity is a key factor for cryptocurrency enthusiasts to compare each other and price their NFTs, and there is even a small industry around cryptocurrency brands that help generate rarity tables for their NFT collections. Many generative music NFT projects, such as SoundArts (above), have implemented a rarity-based approach, whereby developers assign a rarity rating to each merged track (stem) to demonstrate the generative creation process of that music NFT collection.Another mechanism that many generative music NFT projects carry over from the visual world isBlind box minting

, that is, when collectors first purchase an NFT, they do not know the exact feature set or rarity of the NFT they are about to get. For example, artist Julian Mudd's Muddy collection allows collectors to mint a total of 1,000 generative NFTs around his song "Growing Pains," each with a 1,000-piece build around the song's vocals, chords, fills, bass, and percussion. There are thousands of possibilities, and collectors can only know all the details after purchasing, and determine which unique combination of derivatives it is. (The static original version of "Growing Pains" is available on Spotify and other streamers.)

Under normal circumstances, blind box minting projects will trigger the "disclosure" of basic rarity information after all NFTs are minted or after the minting period ends (see which state occurs first). According to this design, the process of blind box minting is very similar to buying loot boxes in video games, or lottery tickets in real life.

"I think there's a weird sense of excitement in not knowing what you're going to get when you mint a coin. That feeling — that we're minting the same price, but what I'm raking may be worth more — taps into our love of gambling. psychological mechanism,” Patrick Price (aka Patty G) said in an interview. He's the founder of the upcoming project 3Q Collectibles, which works with producers who make the foundational merged audio tracks, creating the basis for generative audio NFTs with built-in rarity rankings.

EulerBeats, the flagship NFT generation project in the music field, designed the airdrop like this: 27 one-to-one Genesis "LP". According to the project's terms of service, each Genesis LP has 120 copies (or "prints"), sold on a bonding curve (i.e., each sale automatically increases the price), 8% of print sales go to Genesis LP holders, 2% Goes to EulerBeats, the remaining 90% goes to the Burn Reserve. Further gamification architecture design provides NFT owners with an opportunity to burn the original print in exchange for 90% of the print's current value.

first level title

Social, Cultural and Legal Challenges

While the above strategy is technically feasible for generative/PFP music NFT projects, whether the paradigm is socially, culturally, and legally conceivable at scale is another matter entirely.Assessing the potential market for generative/PFP music NFT collectibles not only financially but also philosophically:Why do people like to listen to and share music in the first place?As an innate social art form, music can be said to be more valuable the more it is shared - so,When it seems like you can mass-produce multiple different versions of music with the push of a button (even though artists may have put in more effort behind the scenes to build the system), does the relationship fans have with music change? How does the traditional top-down notion of celebrity branding — fans following artists because they have unique personalities and voices that cannot be replicated — neatly map onto decentralized infrastructure?

secondary title

01 Lack of social utility

In general, one of the strongest psychological pulls of generative/PFP projects is the ability to bring collectors together under some kind of umbrella community. SoundArts founder Paris Blohm told us in an interview: "Generating PFP is a perfect example of both commonality and uniqueness." Using BAYC as an example, SoundArts founding member Brian Nguyen added: "We are all Apes, but we are in It has its own identity in this community.”

In our database, many generative music NFT projects tend to view NFT ownership as a similar intrinsic community element as a means of accessing and governing their specific DAOs (Holly+, Mudd DAO, BeetsDAO, and BleepsDAO are a few notable examples) . “We see the possibility of building a new kind of fan club by generating NFTs, where NFT holders can receive future airdrops from artists to see their performances,” experimental music/art structures So Lab X, Sound Obsessed, and IN X Kalam Ali, the co-founder of SPACE, told us in an interview, “It is a new form for an artist or band to release a large-scale NFT series, and then gather a fan base based on the NFT owned by the fans. We can see this Formal ideas, while also having decent financial potential, such as using generated NFTs to replace merchandise or even tickets at Metaverse events.”

That said, these community experiences are largely built by Web3-native artists and collectors, while also serving themselves. For various cultural and technical reasons, the mainstream social utility of generative/PFP music NFTs is still much lower than that of their visual counterparts.

First, music is inherently harder to navigate than visual art. In the course of listening to a song, a fan or collector can not only browse through hundreds of visual PFPs, but also quickly analyze the rarity and uniqueness of these visual assets within the same collection. By contrast, assessing the rarity of a particular audio file (such as inferring slight variations between different sources) may not be as intuitive, at least for the everyday consumer.

Also, a big part of the culture around visual generation/PFP NFTs is being able to use them as personal avatars on Twitter, Discord, and other social platforms, especially NFTs designed with human or humanoid characters like BAYC and CryptoPunks . But in most cases, mainstream social platforms do not support music or audio as PFP.These limitations also beg the question:Or, maybe the artist behind the project himself? Putting a humanoid visual layer on generated/PFP music NFTs could be a potential way to push the project to a wider audience, making it more "approachable" to casual fans, especially those already familiar with BAYC . For example, the interactive, generative music NFT project WarpSound (above) performs and outputs music through a virtual, human or human-like swarm of DJs. Whereas with most other similar projects, the visual layer output is just some abstract art.

secondary title

02 Lack of legal recourse

Without embracing the "Remix" culture "Remix"), it is difficult for the visual PFP world to be as successful as it is today-that is, at least give NFT owners some commercial rights to commercialize their tokens. One of the clearest examples of this dynamic is the BAYC community, where owners have full commercial rights to any NFT they own. Today, you can find APE on T-shirts, coffee mugs, hats, comic strips, and countless other products, not to mention in Universal Music Group's new supergroup. This openness to derivative IP has helped BAYC become one of the most financially successful NFT projects ever.

(Importantly, not all PFP projects share this mindset. For example, the creators of CryptoPunks retain the sole right to profit commercially from the project, while CryptoKitty owners $100,000 in sales in a commercialized version. But even these rights are not strictly enforced, and more limited projects often fail to generate more revenue in the wider community. It seems that most PFP projects have decided that Brand expansion and awareness are more important than IP protection).

There are some early, small-scale proofs of concept regarding the open approach of music NFTs to derivative works. For example, the Async platform enables collectors to own NFTs representing the right to alter specific merged tracks in the final master of a song at any given time, and then purchase NFT "prints" of different combinations of those merged tracks (similar to the previous Genesis and Printing Patterns of EulerBeats described). Projects like Audioglyphs and EulerBeats also give original NFT holders the commercial rights to the associated song, as long as they hold the original token.

In fact, even before Web3 and NFTs are considered, the legal issues surrounding generative music creation are a bit of a mess. In most countries, there is no legal standard to say exactly who should be credited for songs that include AI composition or production process, is the software used in the process? Human producer of original bounce or source material? Or some combination of the two? Who is the "legitimate" copyright owner? Specific to generating music NFTs, tokens will only amplify rather than eliminate the deep-rooted legal complexities in the music industry - a trend given that PFP projects are generally free to acquire intellectual property from each other without legal recourse. Perhaps overlooked by the strong anti-copyright ethos of the Web3 community.

Conclusion: creativity as its own (economic) reward

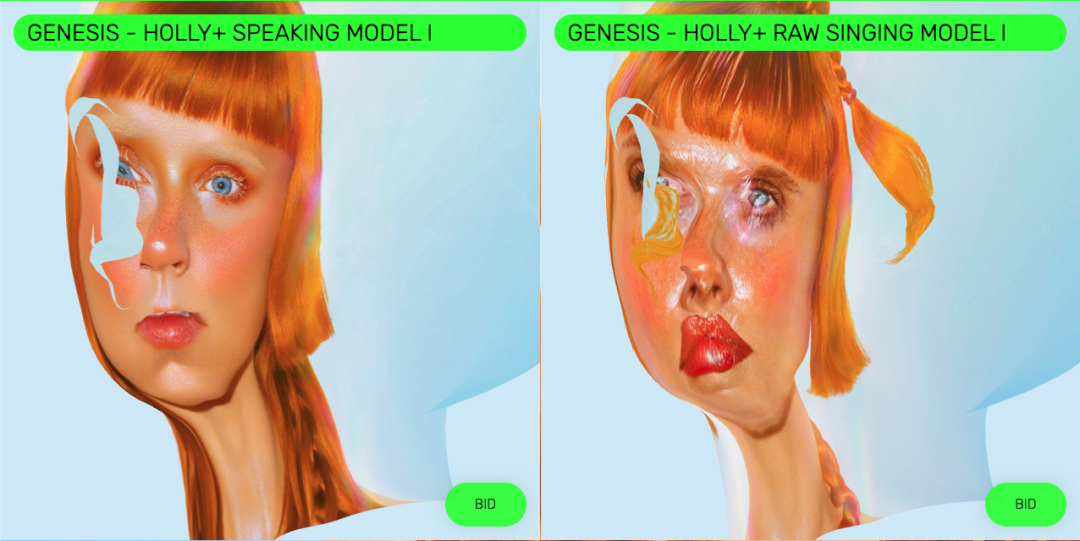

image description

Genesis- HOLLY+ Talking Mode 1 / Genesis- HOLLY+ Singing Mode 1

At the end of the day, consumer/fan demand — and the economic model and value — around generating music NFTs has not been proven for a variety of reasons. However, at least for now, most of the music/Web3 ecosystem is focused on building infrastructure around the artist's well-being, and these limitations also serve as a shield against speculation.

Visual PFP projects like BAYC and CryptoPunks have succeeded not only because they have built shared communities and a sense of identity, but also because they have become tradable assets with some financial utility. In some cases, this has led to a highly speculative digital art market. But the inherent nature of music and the functions it performs in society arguably make it unlikely that it will follow the same speculative lines.So, as a closing note, it is time to consider

What kind of new business model can support the next wave of music NFT explosion, and at the same time, it is not just based on financial speculation.

For artists in this ecosystem (and, long term, probably any artist in Web3), "hyping" NFTs may be the wrong model. Instead, generative music NFT projects can focus more on building a long-term model that earns passive income for original artists, while also empowering collectors to build their own businesses and creative works around the token. Holly+ has taken this approach with their own auction house on Zora (screenshot above), where anyone can submit artwork made using the Holly+ voice model for possible inclusion in the 1/1 NFT collection on the Holly+ DAO platform . 50% of the profits from the sale of these crowdsourced NFTs will be shared with contributing artists, 40% will go to the Holly+DAO treasury to fund new tools, and 10% will go to Holly Herndon as compensation for the use of her digital likeness.Making generative music NFT projects available to artists and the music industry, rather than just fans, may be a potentially interesting financial opportunity to tokenize the fundamental creative process alongside any discrete creative output. “We are interested in studying how NFTs and tokens can be used to tokenize generative music workflows, templates, and datasets,” Ali said, citing open-source, off-chain resources for aggregating generative art models such as Take Pollinations.Ai as inspiration.

“You can use tokens to access certain art datasets, or you can buy an artist’s NFT to license the creative software used to generate that artwork.”

This monetization model is reminiscent of Eno's notion of composers as bottom-up gardeners (as opposed to composers as top-down architects), and how this distinction brings Web3 art back to life. Definition - not only provide completed creative products, but also provide seeds for NFT collectors and other artists to create and monetize derivative works.

"We think this is the way the NFT format pushes art forward, just as the development of recording technology has created the concept of recording artists, the actual recording of music is as much art as the notes or lyrics of the music." Synthopia (a by Gramatik , Luxas, and the Audioglyphs platform’s Generative Music NFT project) told us in a statement, “If NFTs make the economics of generative music work, we think it can do the same.”