Explore Rollup Economics from First Principles

Author: Barnabé Monnot

Original source: barnabe.substack.com

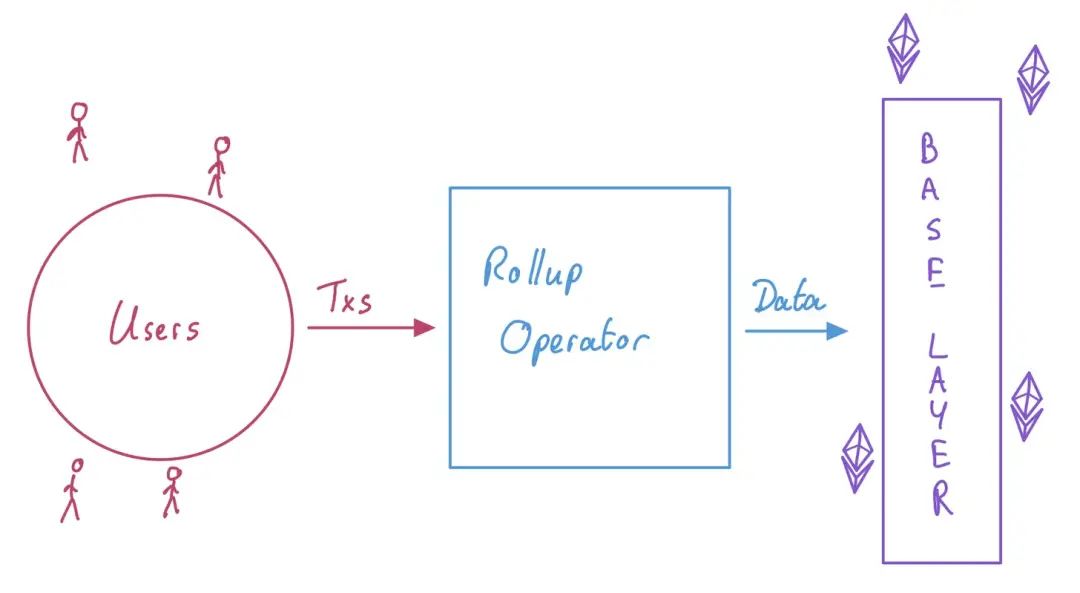

Rollup is an amazing primitive. Rollup will become the preferred solution for Ethereum's future expansion (please refer to the article "Illustrating the Development Route of Ethereum"), and provide a broad design space for operations on Ethereum. In general, rollups extend the protocol on which they are built, and preserve most of the properties of the protocol. The most important thing in the whole process is to ensure the correctness of off-chain execution and the availability of data behind the execution. How to achieve these two points is up to the designer.

Recently I've become interested in understanding rollup from an economic perspective. This is not just a theoretical question. The base layer (L1) is expensive, and we should aggressively provide some room where users can afford transaction fees. Better economics means better pricing and happier users.

first level title

Characters in the Rollup game

Briefly, we will ideally divide into three roles:

Users: Users can send transactions on the L2 network, just like on L1. They hold assets on L2 and interact with contracts deployed on rollup.

Rollup Runner: This role encompasses many other roles. Rollup operators represent all the infrastructure needed to process L2 network transactions. We now have sequencers who issue batches of transactions, executors who issue assertions, challengers who issue fraud proofs, and provers who compute validity proofs (see this essay)...

image description

first level title

Rollup overhead

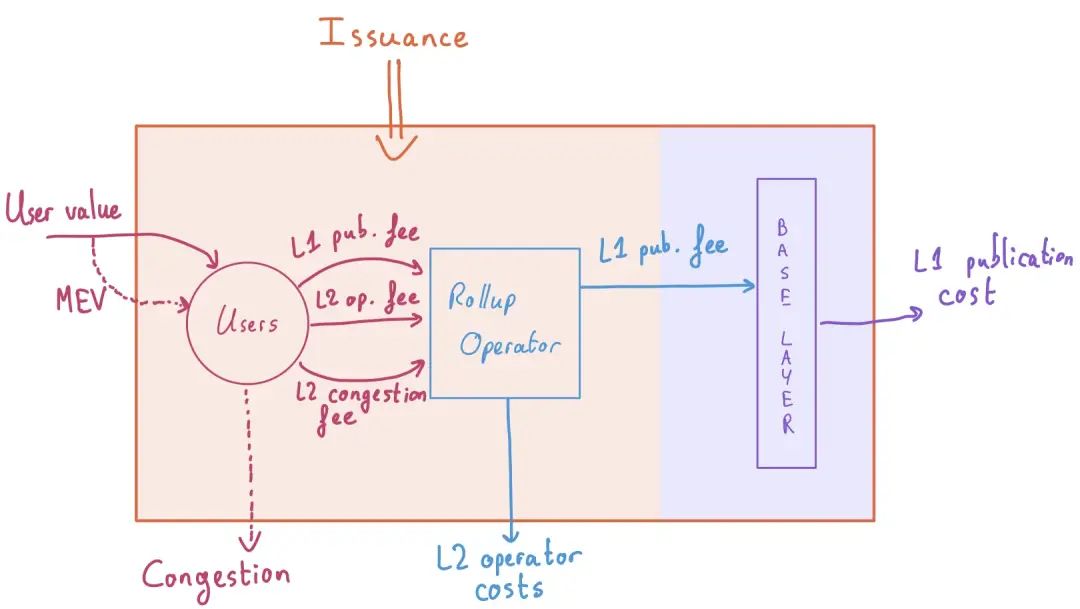

In this article, we look at rollups from a "system" perspective, focusing on their overhead, benefits, and fees. Running a system incurs overhead, which act like "energy sinks" where value flows from within the system to the outside. On the other hand, the system also gains benefits, which are "energy sources", and value flows from outside the system to inside. Fees bridge the "source" and "reservoir" of energy, transferring value between the various components of the system so that each properly performs its function.

For example, in a previous article I wrote about EIP-1559, I explained how to break down the transaction fees paid by users:

Part of the fee for packaged transactions is owned by the operator: in the case of the PoW base layer, the miner's fee is compensation to the miners to hedge against the increased risk of uncle blocks. This fee covers the cost of issuing blocks to operators, making them part of the network. And that's the current default fee of 1 or 2 Gwei when you send a transaction.

The remaining fee payment is used to make its transactions preferentially packaged into the blockchain, that is, pricing congestion. This fee makes the network and users suffering from congestion situations incentive-compatible in the system. This is what the basefee of L1 does under normal circumstances.

secondary title

L2 operator costs (L2 operator costs)

secondary title

L1 data publication costs (L1 data publication costs)

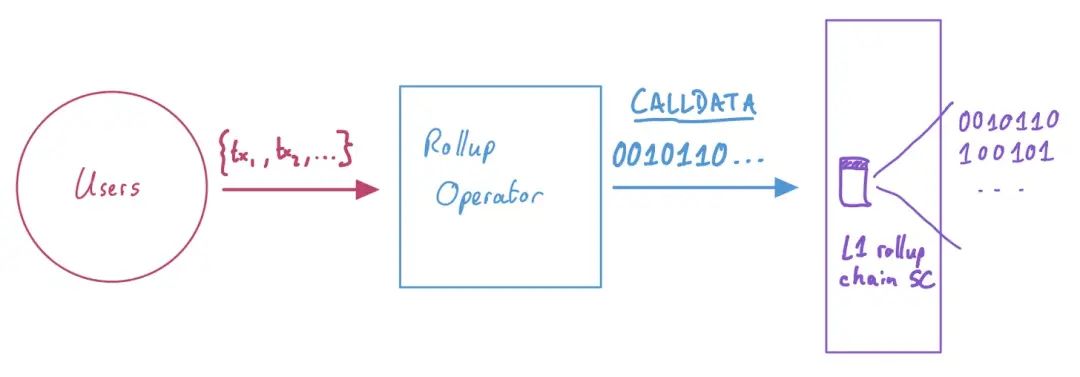

It's worth spending some time researching the overhead of publishing data, as this is really a new type of overhead in the rollup economy. Once the operators have collected a large enough transaction set, they need to publish the compressed information of this transaction set on the base layer. Currently, this process is not done in a particularly elegant way: data is simply published as "CALLDATA", which is a transaction attribute that allows the sender to add an arbitrary sequence of bytes.

image description

Users send transactions, and the operator compresses these transactions and publishes them to the rollup chain smart contract of the base layer

The overhead of publishing data is incurred by the base layer. In order to publish data on Ethereum, the current market price of data is controlled by EIP-1559, where each non-zero byte of CALLDATA consumes 16 gas, and each zero byte consumes 4 gas. With multi-dimensional EIP-1559 (example in Vitalik's simple "Sharding-format blob-carrying transactions (used for sharding carrying blob transaction type"), the price of CALLDATA can be set in its own EIP- 1559 markets, pricing data markets separately from traditional execution markets.

In this Dune analytics dashboard, I try to organize the data published by several major rollups. I'm not sure I captured the full information, especially for zk-rollup. If you find something that doesn't match, please let me know! :)

secondary title

L2 congestion costs

There is a third, more intangible overhead. As long as the supply of rollup block space cannot meet the existing demand, scarce resources must be allocated. In a spherical cow world of time-insensitive users, users simply wait in line. There is no loss of value from a congested system. But when users incur costs due to waiting, they should want to minimize transaction delays as much as possible. For users at the back of the queue, the reduction in their benefits is an added overhead to the overall rollup system.

first level title

Rollup revenue

secondary title

transaction value

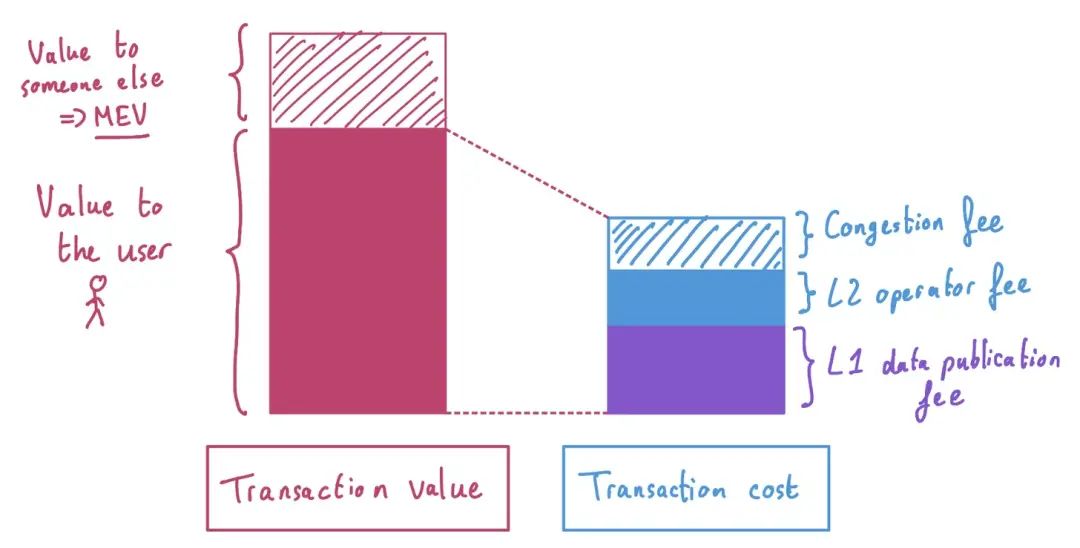

Users get value from transactions on the rollup and nowhere else, and are thus prepared to pay for the services they receive. The value here refers to the utility users get from having their transactions packaged on the rollup. I get $50 in utility if the transaction is included, and I am willing to pay that amount to have my transaction included. If we end up paying $2, my surplus is $48. But from the perspective of the rollup system, no matter who gets $2, the value of the initial inflow is $50.

Second, as long as the transaction contains positive MEV, such as exchange transactions that can be sandwiched on some DEXs, this concept will also be added to our transaction value concept. At this point, it doesn't matter who gets the value, whether it's the sequencer extracting the value, the user sandwiching the transaction, or something else. The only thing that matters here is that our original transaction brought more value to the whole system than the original user got from this transaction. Thus, we derive:

secondary title

Token distribution

The second source of revenue is "token distribution". On the base layer, the income obtained by the block creators is the newly minted tokens, and the original encrypted assets of the network that the block creators help to maintain. These benefits offset their infrastructure overhead, and as long as it is profitable for them to do so, more and more block producers will join.

first level title

Transfer Responsibility: rollup version

In summary, a rollup system includes three parties: users, rollup operators, and the base layer. Running this system incurs three types of overhead: running cost, overhead of publishing data at the base layer, and congestion overhead. The system earns revenue in two forms: transaction value and token issuance.

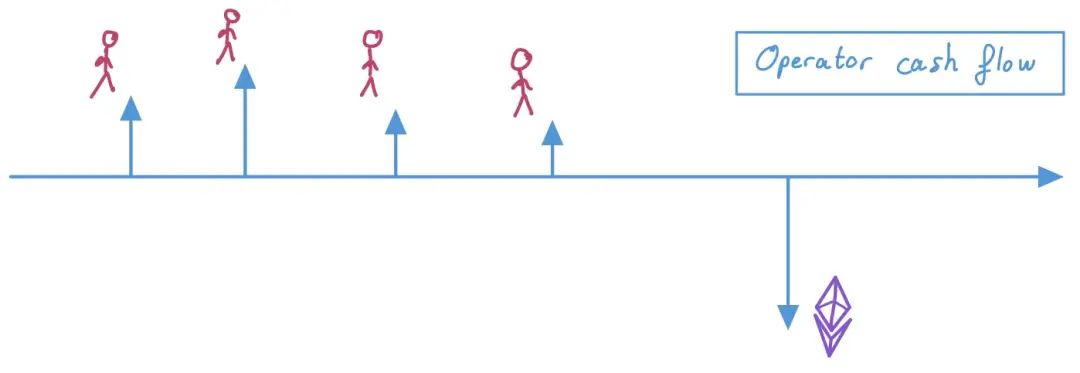

Now all that's left is the game of matching who pays what, and when. Some pairings are easy to handle. The operator must pay the base layer for L1 data publishing. They have to pay the moment they publish the data, and they pay as quoted at the base layer. [2]

image description

secondary title

Budget Balancing: Limits on Passing on Responsibilities

Let's add a new constraint to our system - operator budget balance. We assume that rollup operators cannot operate at a loss, ie their revenue must be at least equal to or greater than their cost. This assumption may not always hold true, however it seems to me that it is crucial if we are concerned with the operator set being sufficiently decentralized and open in the future. If operators need to operate at a loss, this will crowd out participants with less capital and make the size of the operator set very limited. [3] A small set of operators weakens the censorship-resistant guarantees, and in the worst case, users are forced to package their transactions at the base layer, having to pay high fees.

secondary title

Maintain operator budget balance in case of delayed payments

Under the rule of budget balance, we must consider the operator maintaining a non-negative balance. Their main outflow, i.e. L1 data releases, is variable and fee charged separately from their main inflow, i.e. transaction fees. We assume that the operators are fully aware of their L2 operating costs, and quote the exact price to the user at the time of the transaction (similar to the uncle block rate in their cognition and the corresponding miner's fee for compensation). But how are they supposed to provide users with a final L1 data release overhead quote, delaying implementation a bit?

Today, rollup applies heuristics to avoid the risk of variability in L1 data publishing overhead. In one case, the rollup observes the current L1 base fee (thanks to EIP-3198!) and inflates the fee a bit as an extra buffer, i.e. overcharging users in the beginning, in case later operators release Pay more for data. Alternatively, users are charged as a running average function of the L1 base fee to smooth out long-term fluctuations.

The logical solution, in my opinion, is to call derivatives, which are simply L1 base fee futures contracts. At transaction time, users are charged a fee that locks in a future price to pay for publishing data on the base layer. By reducing pessimistic overpayments, the balance is sent back to the user. Current research is inconclusive regarding the optimal design of such derivatives.

image description

secondary title

What about congestion charges?

Assuming that rollups price congestion charges perfectly when users transact, there will now be a benefit in the form of congestion charges. Today, on the Ethereum base layer, those fees are burned. The primary reason for this is incentive compatibility: if the congestion fee goes back to the block producer, the protocol's base fee offer is no longer binding, defeating the purpose of EIP-1559. But burning base fees is not the only option for maintaining incentive compatibility.

It has been proposed that all 'rollup exhaust', ie the costs caused by economic externalities (such as congestion or MEVs), be used to finance public goods. [4] This is not a bad solution. Congestion pricing in cities is often earmarked for improving public transport systems, that is, the money is used to compensate for the negative externalities that, when priced accordingly, lead to these benefits.

Note that I actually slipped MEV in here...why should we think of MEV like congestion charging? First, because MEV is as much an externality as congestion. The simple act of issuing a transaction with MEV creates a positive externality for those who want to capture it. [5] Externalities are "unmatched value", that is, they arise from some primitive economic activity that balances useful work with compensation (e.g., users pay L2 operators overhead; operators pay L1 release overhead) , but they make or break some extra value in the process.

This is most clearly illustrated in the concept of MEV auctions, a design in which operators compete for the right to package a block based on how much value they can extract from packaged blocks. This value implies congestion overhead, which users express by competing with each other for bids. More obvious is the MEV itself, which operators will compete for. Again, assuming runners are not allowed to operate at a loss, their bids must reflect their true ability to extract value from blocks, i.e. runners will sum their transaction batch fees to users plus their The MEV extracted in the transaction batch is used for bidding. At the same time, assuming that all operators have to pay the same amount of L2 operator overhead, and L1 data publishing overhead is charged to users precisely, we can get:

User fee = L1 data publishing fee + L2 operator fee + L2 congestion fee

Runner Overhead = L2 Runner Overhead + L1 Data Publish Overhead

Operator revenue = user fee + MEV

Operator Profit = Operator Revenue - Operator Overhead = L2 Congestion Charge + MEV

In an environment where operators compete in an efficient market for the right to propose blocks, operators must simultaneously bid for their entire profit, namely the congestion fee and the available MEV in their transaction batch. [6] This is the implicit value of the system: the first comes from the fees that users pay to avoid losses caused by congestion, and the second comes from the ripple effect caused by the initial transaction. These values belong to no one in the first place, so why can't they be captured and redistributed?

first level title

Explore rollup economics

This article makes a lot of assumptions. For example, I assume "runner budget balance" because I believe the community should look critically at rollups run by runners at a loss, which may not yet be suitable for decentralization. Token issuance helps re-establish budget balance, although this relies on an exogenous price signal (token value) to coordinate operator incentives. In this view, operators prefer to price as accurately as possible what they can, namely their L2 operator overhead and L1 data distribution costs. This avoids a misallocation of future earnings where operators would expect a higher token price to pay for their operations. [7]

first level title

other resources

John Adler's "Wait, it's all resource pricing?" (slides and video here) gives background on the separation of L2 runner overhead, execution and data availability overhead.

Patrick McCorry, Chris Buckland, Bennet Yee, Dawn Song, SoK: Validating Bridges as a Scaling Solution for Blockchains

Many thanks to Anders Elowsson, Vitalik Buterin, Fred Lacs, and Alex Obadia for their many helpful comments.

1. Vitalik also believes that this overhead is the opportunity cost of the block space provider. In this reading, if your transaction is included, you should at least pay the provider what they would have earned from including other transactions.

2. This means we can further unlock our models. The data release cost is quoted by predicting and quoting the congestion situation of the base layer, which forms a whole with the operator of the base layer, that is, the block producer.

3. The centralization of the operator set may not be as bad as the centralization of block producers in the base layer, but the evaluation of the decentralization tradeoffs of the rollup network is left for the future.

4. At the time of writing, even those misallocated fees, such as those collected from users to cover the cost of publishing data, are used to fund some public goods, like the retrospective public goods funding scheme initiated by Optimism.

5. Interestingly, the gas price auction, which is used to capture positive externalities, creates negative externalities for the entire network, making the network have to deal with more severe congestion!

6. Note that invalidation efficiency is no longer a fair assumption in cases where some operators have access to private transaction order flow, or participate in cross-domain MEVs (kudos to Alex Obadia!). In the latter case, market efficiencies in cross-domain extractors can be recreated in single-domain builder auctions.

7. By the way, this mode is not terrible! This is mostly how miners have always operated. However, we must remember that any additional risk borne by the operator is a centralized pressure unless there are risk management primitives such as derivatives available. Even with such options for hedging risk, the knowledge required to run a good business can be high, which can discourage less-skilled operators.