Paradigm: Analyzing how the NFT fragmentation scheme RICKS solves the reorganization problem

content directory

content directory

1 Introduction

2. Today's NFT fragmentation

2.1. Reorganization issues

2.2. Buyout auction

2.3. Purpose of Buyout Auction

2.4. Unexpected buyout

2.5. Reserve price

3 Real Case Study: Zombie Punk Buyout

3.1. Buyout

3.2. Unhappy holders

4、RICKS

4.1. Overview

4.2. Examples

4.3. Potential outcomes

4.4. Complete the buyout

4.5. Auction details

5. Additional functions

5.1. Arbitrage

5.2. Auction reserve price

5.3. Fragmented release

5.4. Apply for auction proceeds

introduce

1

introduce

Benbit introduces a new NFT fragmentation primitive: RICKS (full name is Recurrently Issued Collectively Kept Shards).

When you split your NFT into RICKS, the protocol mints new shards and sells them at a constant rate (eg 1% per day or 5% per month). Proceeds will be distributed to existing RICKS holders as staking rewards.

This design solves the reorganization problem, ensuring RICKS is always convertible back to its underlying NFT, while avoiding the liquidity and coordination issues of all-or-nothing buyout auctions.

2

Fragmentation of NFT today

2.1 Reorganization problem

It is very difficult to split NFT, because it will face an all-or-nothing problem.

If you want to sell 25% of 8 cookies, you can sell two of them, and if you want to sell 25% of a business, you can sell the rights to 25% of its future cash flow. In either case, the remaining 75% is still useful to you.

On the other hand, owning 75% of an in-game asset may not allow you to use a portion of that asset in a given game. If you sell 25% of such an asset to a buyer and they refuse to sell it back, or even lose their private keys, then you're in trouble. Even if you nominally own 99.99% of an NFT, that ownership could become worthless due to the inability to restructure the NFT.

Therefore, fragmentation protocols must provide some way to reassemble NFT fragments back into the original NFT, and we refer to this design constraint as the reorganization problem.

2.2 Buyout problem

By far the most popular solution pioneered by fractional.art is the Buyout auction.

Situation: Alice sells 25% of her NFT to Bob using a shard protocol with a buyout auction mechanism.

Buyout Auction: A third-party Clara can trigger a buyout auction for a fragmented NFT at any time: whoever bids the highest ETH (probably Clara) will get the entire NFT, and the sales proceeds will be distributed to Alice and Bob in a 75/25 ratio.

2.3 Purpose of Buyout Auction

The buyout auction exists to ensure that Alice and Bob's shards retain their fair market value by solving the reorganization problem.

To see why, suppose Alice splits her NFT (representing an in-game asset) into 100 shards using a protocol that doesn't offer a buyout auction, in which case only the person who owns all 100 shards will be able to rebuild the NFT.

If someone accidentally destroys or loses one of these 100 shards, no one will be able to rebuild this NFT and the remaining shards will lose all value. Due to this risk, even when fragmented, each of the 100 fragments is worth much less than 1/100 of the original NFT value.

With a buyout auction, losing one of the shards no longer destroys the value of the other shards. For example, if Alice lost one of her shards immediately after minting, she could initiate a buyout auction and submit the winning bid to get the NFT back, with 99% of the proceeds going to her.

In this sense, buyout auctions are less a feature than a necessary evil. They are certainly not for the benefit of potentially interested buyers like Clara, who were not stakeholders in fragmented NFTs in the first place, and therefore not worthy of special consideration by the protocol.

2.4 Unexpected buyout

Unfortunately, buyouts can be problematic due to funding constraints: if the NFT is valuable enough, no one may be able to raise enough money to pay a fair price once the auction starts.

For example:

Alice has an NFT worth 1,000 ETH, she splits it using a sharding protocol with a buyout auction mechanism, and sells 50% of the shards to Bob. Then, market conditions changed abruptly, and the fair value of this NFT jumped to 100,000 ETH, which is what the NFT could have fetched if it were sold in the best possible condition (such as at a Christie’s auction event).

Capital constraints: It may not be realistic to find a buyer willing to buy the NFT at its full valuation in a short period of time. Maybe this NFT will only get a maximum of 10,000 ETH in an on-chain auction within a week.

Shard holders disagree: Since 10,000 ETH is far below the fair value of this NFT, Alice would strongly object to selling at this price. Bob, on the other hand, does not have a strong sense of fair value and is willing to sell this NFT for a lower price, which is still 10 times his original purchase price, so that he can buy other NFTs he prefers.

Collector Opportunity: Clara, a savvy collector, spotted this opportunity and initiated a 10,000 ETH buyout auction. No one, including Alice, could beat Clara's bid in a short period of time, so she won ownership of this NFT, which she then sold at a Christie's auction for 100,000 ETH a few months later.

2.5 Reserve Price

To avoid this, fractional.art includes a reserve price in its buyout auction mechanism, which specifies the lowest price at which a buyout auction can be initiated. In the above example, if the reserve price is set to 100,000 ETH, Clara will not be able to initiate the auction at 10,000 ETH.

The problem comes when the user tries to set a reserve price. In the example above, Alice doesn't want to sell the NFT for much less than the fair value of 100,000 ETH, but Bob doesn't mind. Reaching an agreement here can be difficult and contentious, especially when the parties involved may change as pieces change hands.

In practice, setting floor prices requires the active participation of shard owners. Therefore, they are not updated very often due to the attention demands of the participants. No one has yet found a floor price mechanism to solve the problem of unexpected buyouts.

3

Real Case Study: Zombie Punk Buyout

The Party of the Living Dead is a group of NFT enthusiasts who banded together to bid on a rare zombie CryptoPunk, which they bought for 1200 ETH, and which they then shared on fractional.art Fragmentation is performed and the fragments are distributed to contributors in proportion to their contributions.

During the initial fragmentation process, 5 whale addresses collectively owned 56% of the NFT fragments, while the rest of the fragments were distributed among 451 other participants.

3.1 Buyout

Pieces of this Zombie Punk were then traded on Uniswap, and an anonymous collector realized that the pieces were undervalued relative to the value of other Zombie Punks. The collector purchased enough fragments to increase his personal reserve price voting power, then lowered the buyout reserve price and initiated a buyout auction.

The buyout auction started at 1,100 ETH (less than the buyout price of the Party of the Living Dead) and ended at 1,900 ETH.

Note: If you contributed to this PartyBid, please make sure you collect your dead token here so you can claim your final buyout price portion here.

3.2 Unhappy Fragment Holder

Many non-whale fragment holders were not happy with the buyout bid, believing the purchase price was too low.

Unfortunately, they found themselves largely helpless. Taken individually, none of them would have been able to acquire enough liquidity to beat the bids and buy the NFT outright. Even if they wanted to join forces to buy NFTs as a single bidder, the overhead of coordination along with the limited time available makes this path infeasible.

4

RICKS

4.1 Overview

RICKS solves the restructuring problem while avoiding the liquidity and coordination problems of a full buyout.

The protocol is not an all-or-nothing buyout auction mechanism, but instead issues new RICKS for a given NFT at a constant rate (for example, 1% per day, or 5% per month), and these new RICKS are distributed in the auction Sold in ETH, proceeds will be provided to existing RICKS holders as staking rewards.

As we'll explain below, liquidity-constrained buyers looking to increase their ownership can always trigger auctions that add less than a full day's worth of new RICKS.

This means that the ownership of the NFT always flows gradually to whoever is willing to pay the most for it, while existing owners benefit from it.

for example:

for example:

When Alice's NFT is worth 1000 ETH, she uses the RICKS mechanism to sell 50% of her NFT fragments to Bob. Now, market conditions have changed and the fair value of the NFT at the time of the best execution sale is 100,000 ETH. However, no one can provide it with that much liquidity in a short period of time.

Fragment holders are divided: Clara, a third party, wants to buy the entire NFT at a price of 10,000 ETH. Bob is satisfied with this proposal, but Alice disagrees. She does not want to sell this NFT at a price lower than the fair value. At this point, Alice and Bob each have 50 RICKS (100 total), and the issuance rate is 1%.

Collector Opportunity: Clara participates in the daily auction and bids at an estimate of 10,000 ETH, for 1% of this NFT, a RICKS totals 100 ETH.

Protect fair price: Alice realizes that this bid is too low, and bids at a valuation of 90,000 ETH, or 900 ETH to buy one RICKS. Since she owns half of the existing RICKS and will receive half of the auction proceeds, she only needs to contribute 450 ETH to fund her bid.

4.2 Potential outcomes

Afterwards, one of two outcomes may occur:

1. If Clara's bid does not exceed Alice's, Alice will win the auction. She will pay Bob 450 ETH and will receive one additional RICKS, so she now owns 51/101 RICKS, or 50.5% of the supply. Alice and Bob trade with each other at what they both deem favorable.

2. If Clara outbids Alice by, say, paying a fair price of 1,000 ETH, then Alice and Bob will each receive 500 ETH, and Clara will receive one RICKS, so she now owns 1/101 of a shard, or slightly less 1%. Likewise, Alice, Bob, and Clara all trade at prices they are satisfied with.

Either way, if this activity persists over time, it will attract attention and buyer liquidity, increasing the likelihood of a fair price transaction for all parties involved.

4.3 Complete the buyout

Assuming that Clara's goal is to own this NFT, she repeatedly bids for RICKS at a valuation of 100,000 ETH, a price no one else can match. Eventually, she owns 99% of RICKS (maybe 458 days after winning the auction), and now, she wants to claim this NFT, for which an additional mechanism will be required in the protocol.

One way is to admit that RICKS has some inherent flaws and use a kind of lottery mechanism. For example, if a holder controls 99% of the NFT's pieces, they might trigger a coin flip where if the coin lands heads, they get the entire NFT (so they get an extra 1%), and if it lands tails, Then the other owner's position will be doubled (thus, this holder will lose 1%). From an expected value standpoint, the procedure is perfectly fair.

In order to avoid strange situations near the 99% boundary, we can allow the major shareholders of NFT fragments to trigger the coin toss program at 98%, 90% or even 75%, but it should be noted that the farther away from the 99% threshold, The less likely it is to win the rest of the shards.

4.4 Auction Details

If fragmented NFTs become expensive enough, even a 1% bid could become prohibitively expensive for most people. Also, on some days, there may be no one interested in the auction, so holding an auction would be a waste.

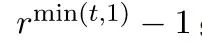

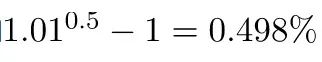

Therefore, instead of holding auctions every day, the RICKS protocol can implement an on-demand auction system: if it has been t days since the last auction, and the issuance rate is r/day, then the protocol will auction

pieces. We take the minimum of elapsed time and 1 day to avoid sending too many RICKS at once.

For example, if the issuance rate is 1% per day, so r=1.01, and half a day has passed since the last auction when a new auction is triggered, the protocol will issue and sell

new supply of RICKS.

5

Additional features

5.1 Arbitrage

Just like the current fragmented NFT, we hope that RICK can be traded on AMM DEX such as Uniswap. This provides a convenient arbitrage mechanism to ensure that RICKS auctions are not completed at too low a price: if the closing price of the auction is significantly lower than the RICKS price on Uniswap, arbitrageurs can buy RICKS at the auction and immediately sell Sell on Uniswap for profit.

5.2 Auction reserve price

We could consider taking this logic a step further and specifying that RICKS auction bids must be at least 5% or 10% higher than the Uniswap TWAP price.

Because a sufficiently aggressive buyer can still accumulate ownership of the NFT over a sufficiently long time frame, the reorganization problem will still be resolved. And, since auctions trade at a premium to Uniswap, they are likely to create minimal selling pressure.

On the other hand, this modification would reduce the consistency of staking rewards for RICKS holders. It also makes restructuring more difficult, and it is difficult to judge a priori its impact on the market.

5.3 Fragmented release

RICKS provides a natural mechanism to start new partial shards of NFTs. Instead of having to provide shards on Uniswap and choose a price, NFT owners can simply use RICKS to split, start as 100% owners themselves, and let An automated auction handles the rest.

5.4 Apply for auction proceeds

RICKS holders need to pledge their RICKS to obtain auction proceeds.

However, this poses a challenge for composability. In particular, it has never been possible to determine how many RICKS are held by each centralized liquidity position on Uniswap V3, which means that auction proceeds cannot be provided directly to Uniswap V3 liquidity providers.

Instead, the RICKS protocol will keep track of the total RICKS owned by all Uniswap V3 LPs, and use the auction proceeds from all of these for liquidity mining rewards for Uniswap V3 pools, as described in this article. In this way, market participants are incentivized to provide liquidity to the pool as efficiently as possible.

Next step

6

Next step

We hope RICKS will make NFT fragmentation more interesting and useful.

This article comes from Tao of Yuan Universe, reproduced with authorization.

This article comes from Tao of Yuan Universe, reproduced with authorization.