Analysis of Federated Learning Framework

【Preface】

▲ Review of the federated learning problem As mentioned above, in 2016, Google proposed a new method for training the input method model, called "federated learning". As time goes by, federated learning is no longer a simple solution to the Google input method model, and a new learning model has been formed. The problem solved by federated learning is usually called TMMPP--Training Machine Learning Models over multiple data sources with Privacy, that is, to jointly complete the training of a predetermined model while ensuring that the data of multiple participants is not leaked. In the TMMPP problem solved by federated learning, n data cubes (Data Controller) {D1, D2,...Dn} are included, and each data cube corresponds to n data {P1, P2,... Pn}. From the perspective of the training mode of federated learning, after selecting the federated learning algorithm that needs to be trained, it is necessary to provide corresponding input for federated learning, and finally obtain the output after training.

Input of federated learning (Input): Each data party uses the raw data Di owned by Pi as the input of joint modeling and enters it into the process of federated learning.

The output of federated learning (Output): Combine the data of all participants, and federately train the global model M (during the training process, no information about the original data of any data party is disclosed to other entities).

▲ Challenges encountered in federated learning

Federated learning technology is still in continuous improvement. In the process of development, federated learning will encounter three major challenges, which are statistical challenges, efficiency challenges, and security challenges.

[Statistical challenges] Statistical challenges are challenges caused by differences in the distribution or amount of data of different users during the execution of federated learning;

a) Non-independent and identically distributed data (Non-IID data), that is, the data distribution of different users is not independent, and there are obvious distribution differences. For example, Party A has rice planting data in northern China, while Party B has rice planting data in southern China Data, due to the influence of latitude, climate, humanities, etc., the data of both parties are not subject to the same distribution;

b) Unbalanced data (Unbalanced data), that is, there are obvious differences in the amount of data of users. For example, a giant company holds nearly tens of millions of data, while a small company only holds tens of thousands of pieces of data. The impact of data on giant companies is minimal, and it is difficult to contribute to model training.

[Efficiency Challenge] Efficiency challenges refer to the challenges caused by the local computing and communication consumption of each node in federated learning;

a) Communication overhead, that is, the communication between user (participant) nodes, usually refers to the amount of data transmitted between each user under the premise of limited bandwidth, the larger the amount of data, the higher the communication loss;

b) Computational complexity, that is, the computational complexity based on the underlying encryption protocol, usually refers to the time complexity of the underlying encryption protocol calculation, the more complex the calculation logic of the algorithm, the more time it takes.

[Security challenges] Security challenges refer to challenges such as information cracking and poisoning caused by different users using different attack methods during the federated learning process;

a) Semi-honest model, that is, each user honestly implements all protocols in federated learning, but uses the obtained information to try to analyze and push back other people's data;

b) Malicious model, that is, there are clients who will not strictly abide by the agreement between nodes, and may poison the original data or intermediate data to destroy the federated learning process.

[Common framework for federated learning]

Facing the above three challenges, the academic community has conducted targeted research and proposed many effective and dedicated federated learning frameworks to optimize the federated learning training process. We briefly introduce these frameworks below.

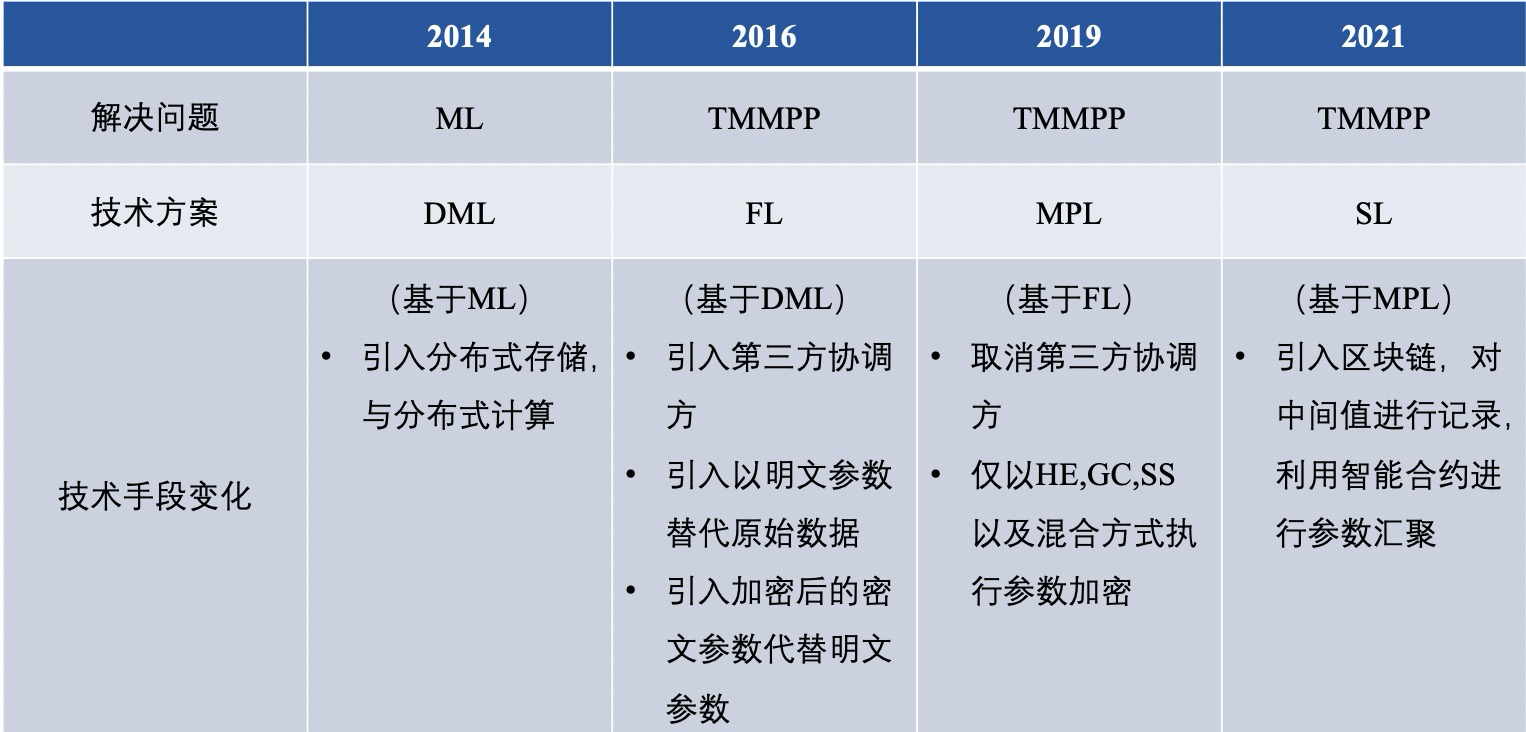

Federated Learning 1.0 – Traditional Federated Learning

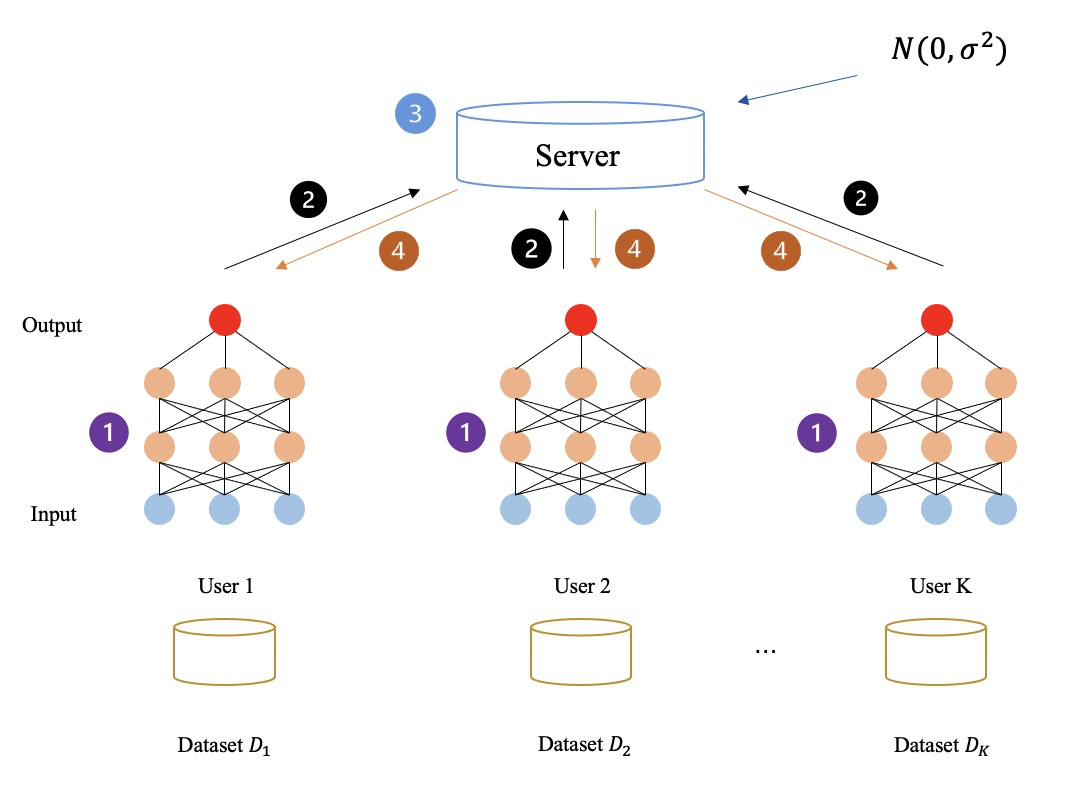

First of all, let's re-explain the concept and principle of federated learning: there are several participants and collaborators to jointly perform federated learning tasks, and the participants (that is, data owners) generate intermediate data similar to gradients through preset federated learning algorithms , handed over to the coordinator for further processing, and then returned to each participant to prepare for the next round of training.

Repeatedly, the federated learning task is completed. Throughout the task, the local data of the participants is not exchanged in each FL framework, but the parameters (such as gradients) transmitted between the coordinator and the participants may leak sensitive information.

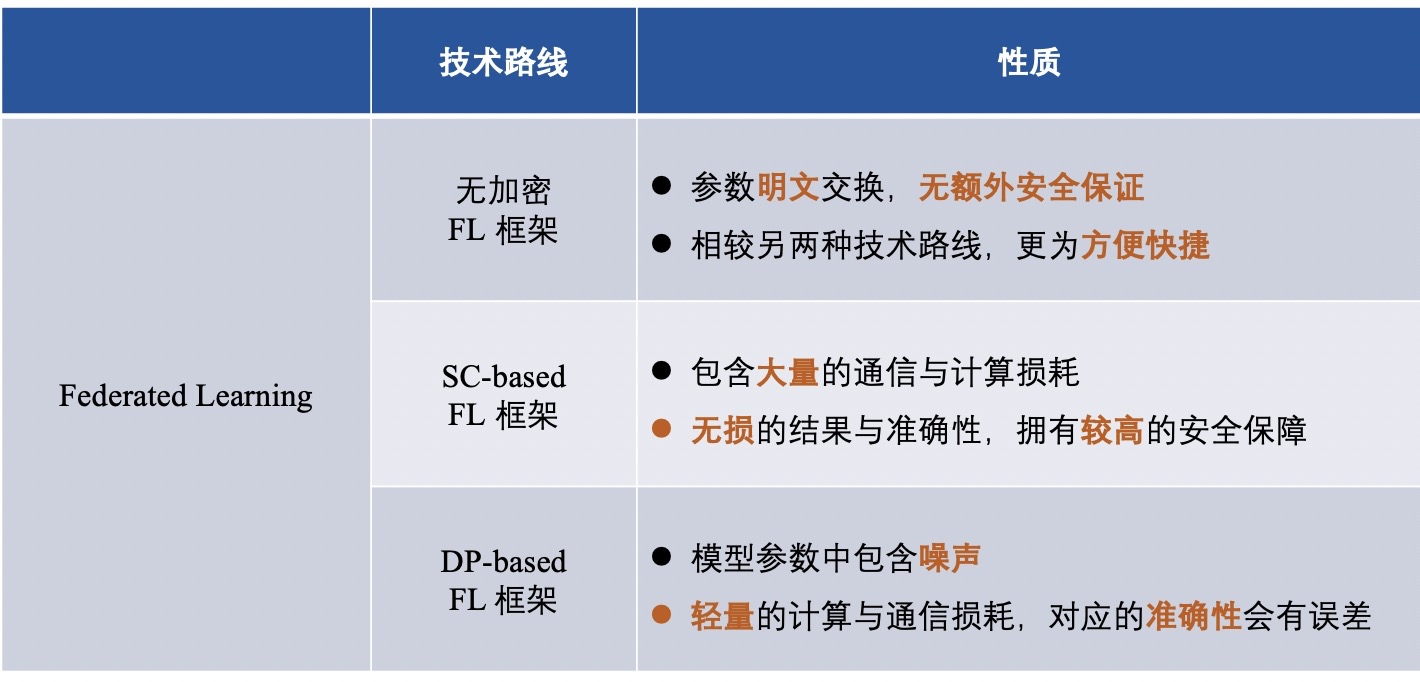

In order to protect the local data of the data owner from being leaked and to preserve the privacy of intermediate data during training, some privacy techniques are applied in the framework of FL to privately exchange parameters when the participants interact with the coordinator. Further, from the perspective of the privacy protection mechanism used in the FL framework, the FL framework is divided into:

1) Non-encrypted federated learning framework (that is, no information is encrypted);

2) A federated learning framework based on differential privacy (using differential privacy to confuse and encrypt information);

3) A federated learning framework based on secure multi-party computing (use secure multi-party computing to encrypt information);

▲ Non-encrypted federated learning framework

Many FL frameworks focus on improving efficiency or addressing the challenges of statistical heterogeneity, while ignoring the potential risks posed by exchanging plaintext parameters.

In 2015, FedCS[3], a mobile edge computing framework for machine learning proposed by Nishio et al., can execute FL quickly and efficiently based on the setting of heterogeneous data owners.

In 2017, Smith et al. proposed a system-aware optimization framework called MOCHA[2], which combines FL with multi-task learning, and uses multi-task learning to deal with statistical challenges. Non-uniformly distributed data and Various challenges caused by differences in data volumes.

In the same year, Liang et al. proposed LG-FEDAVG [4] combined with local representation learning. They show that local models can better handle heterogeneous data and efficiently learn fair representations, obfuscating protected properties.

As shown in the figure below: the federated learning process does not encrypt any intermediate data at all, and all intermediate data (such as gradients) are transmitted and calculated in plain text. Through the above methods, the participants finally learn together to obtain a federated learning model.

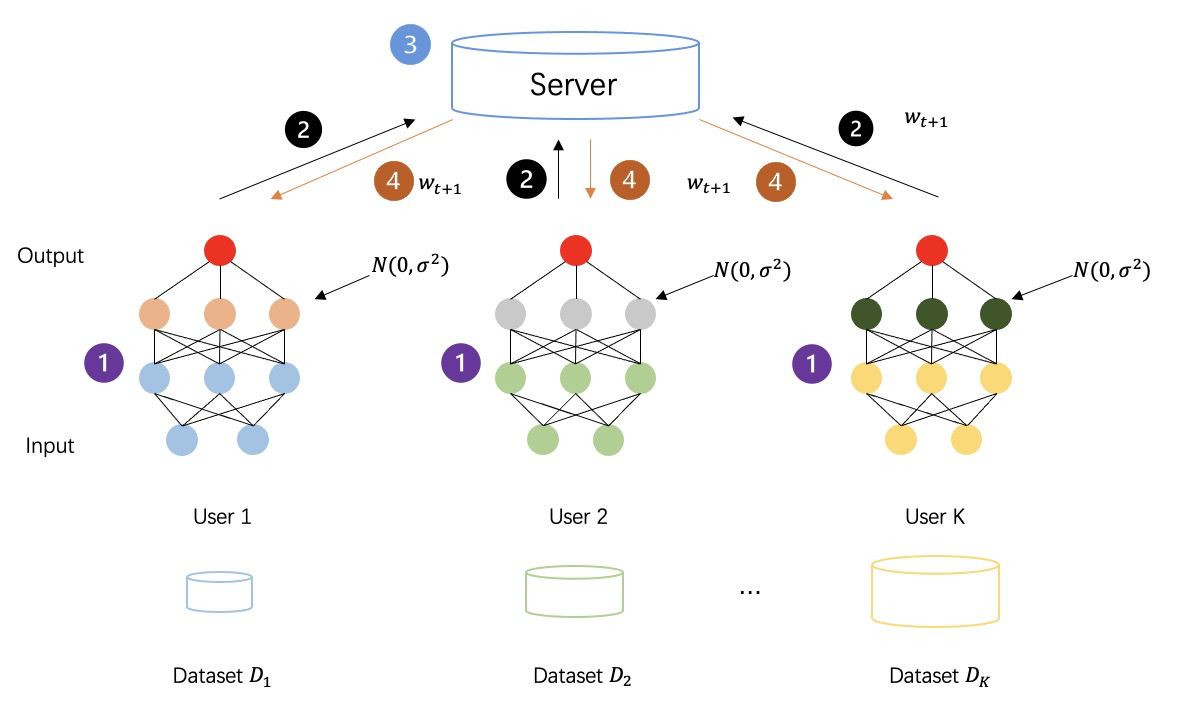

▲ Federated learning framework based on differential privacy

Differential privacy (DP) is a privacy technique [5-7] with strong information-theoretic guarantees for adding noise to data [8-10]. A dataset satisfying DP is resistant to any analysis of private data, in other words, the obtained data adversaries are almost useless for inferring other data in the same dataset. By adding random noise to raw data or model parameters, DP provides statistical privacy guarantees for individual records, making the data irretrievable to protect the privacy of data owners.

As shown in the figure below: the federated learning process after adopting differential privacy to encrypt the intermediate data, the intermediate data generated by all parties is no longer plaintext transmission calculation, but the privacy data with added noise, so as to further enhance the security of the training process sex.

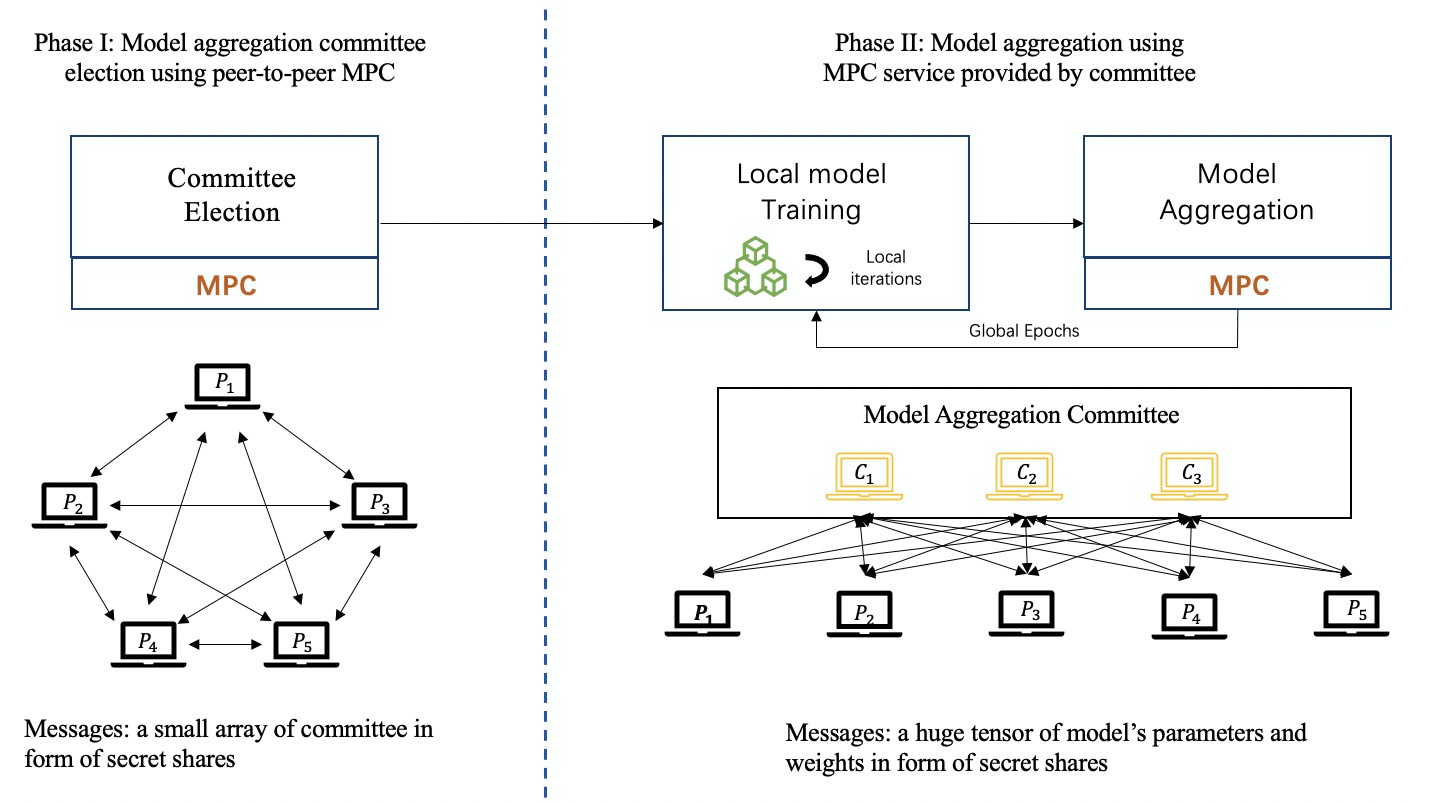

▲ Federated learning framework based on secure multi-party computing

In the FL framework, methods such as homomorphic encryption (HE) and secure multi-party computation (MPC) have been widely used, but they only reveal the calculation results to the participants and coordinators, and do not disclose any information other than the calculation results during the process. additional information.

In fact, HE is applied to the FL framework in a similar way to the secure multi-party learning (MPL) framework (a framework derived from FL, the MPL framework is described in detail below), with slightly different details. In the FL framework, HE is used to protect the privacy of model parameters (such as gradients) interacting between participants and coordinators, instead of directly protecting the data interacting between participants like HE applied in the MPL framework. [1] apply Additive Homomorphism (AHE) in the FL model to preserve the privacy of gradients to provide security against semi-integrity centralized coordinators.

MPC involves many aspects, and retains the original accuracy, with a high security guarantee. MPC guarantees that each party knows nothing but the outcome. Therefore MPC can be applied to FL models for safe aggregation and protection of local models. In the MPC-based FL framework, the centralized coordinator cannot obtain any local information and local updates, but obtains aggregated results in each round of collaboration. However, if the MPC technique is applied in the FL framework, a large amount of additional communication and computation costs will be incurred.

So far, secret sharing (SS) is the most widely used MPC-based protocol in the FL framework, especially Shamir's SS [24].

As shown in the figure below: In the MPC-based federated learning training process, a group of committee members will be fairly elected by the participants as coordinators, and the MPC technology will be implemented to collaborate to complete the task of model aggregation.

After introducing the three FL frameworks, we summarize the framework differences of different technical routes, as follows:

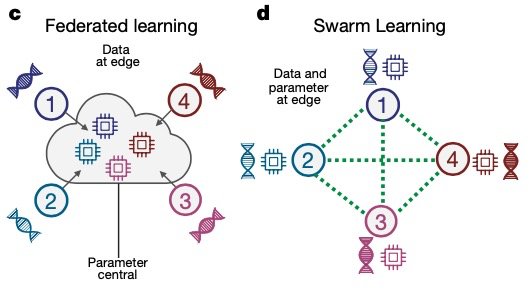

Federated Learning 2.0 -- Secure Multi-party Learning

We mentioned above "secure multi-party learning", which is a term derived from federated learning. Simply put, it is: federated learning without third-party collaborators is called secure multi-party learning (MPL). The FL distinction introduced. In other words, on the basis of federated learning, secure multi-party learning eliminates the coordinator in the traditional federated learning model, weakens the ability of the coordinator, replaces the original star network with a peer-to-peer network and makes all participants have the same status.

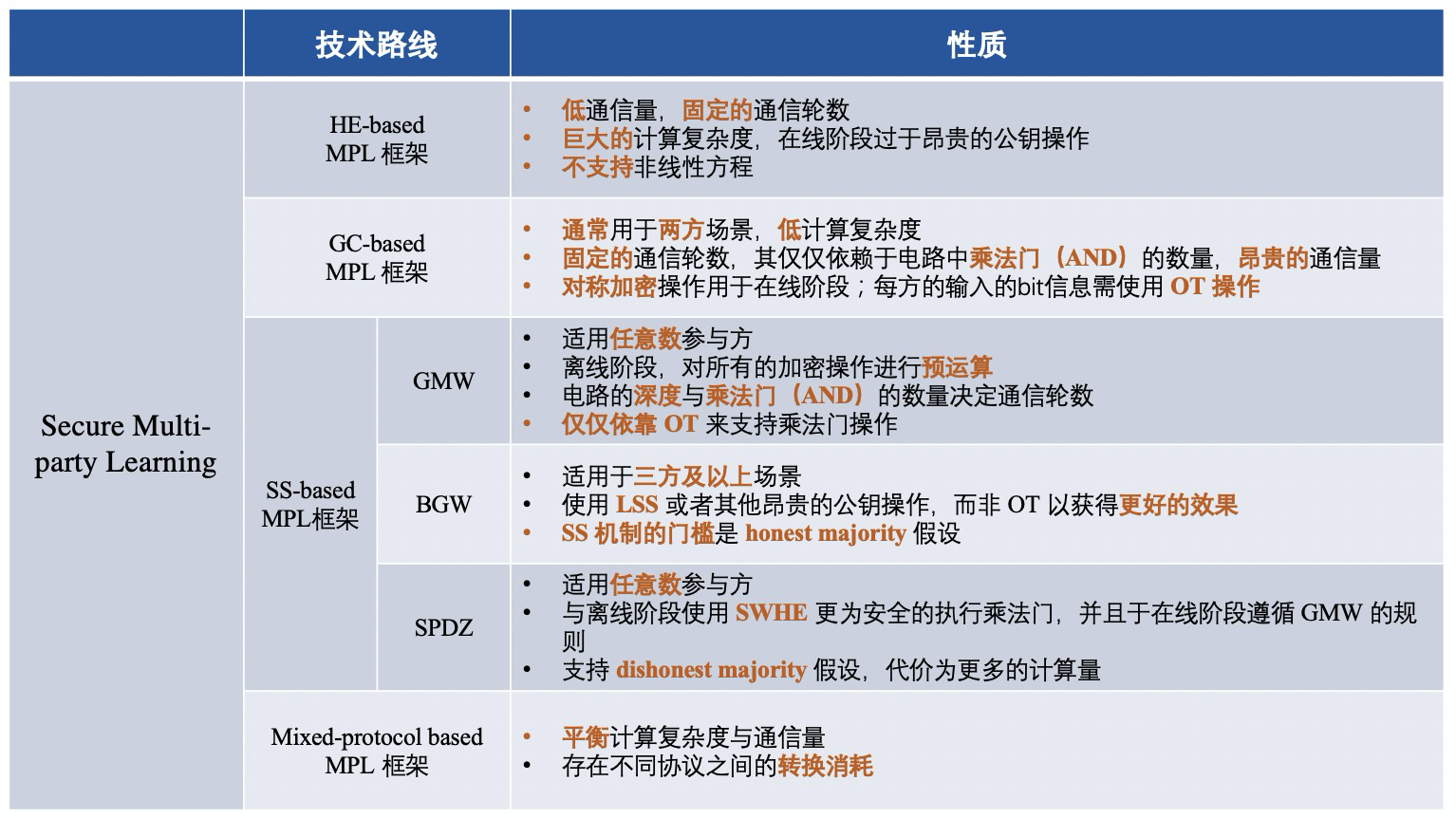

The framework of MPL can be roughly divided into four categories, including:

1) MPL framework based on homomorphic encryption (HE);

2) MPL framework based on Confused Circuit (GC);

3) MPL framework based on secret sharing (SS);

4) MPL framework based on hybrid protocol;

Simply put, different MPL frameworks are: frameworks that use different cryptographic protocols to ensure the security of intermediate data. The process of MPL is roughly similar to that of FL. Let's take a look at the four cryptographic protocols used:

▲ Homomorphic encryption (HE)

Homomorphic encryption (HE) is a form of encryption in which we can directly perform specific algebraic operations on ciphertext without decrypting or knowing the key. It then produces an encrypted result whose decrypted result is exactly the same as the result of the same operation performed on the plaintext.

HE can be divided into "three types": 1) Partially homomorphic encryption (PHE), PHE only allows an unlimited number of operations (addition or multiplication); 2)-3) Limited homomorphic encryption (SWHE) and identical Stateful Encryption (FHE), for simultaneous addition and multiplication SWHE and FHE in ciphertext. SWHE can perform certain types of operations a limited number of times, while FHE can process all operations an unlimited number of times. The computational complexity of FHE is much more expensive than SWHE and PHE.

▲ Confusion circuit (GC)

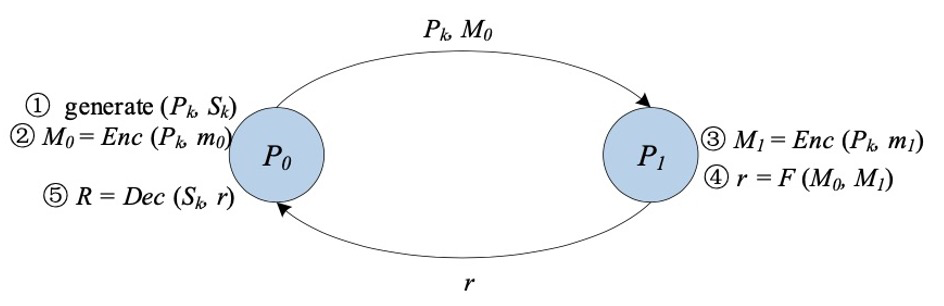

Confusion circuit[11][12] (GC), also known as Yao's confusion circuit, is a secure two-party computing underlying technology proposed by Academician Yao Qizhi. GC provides an interactive protocol for two parties (a garbler and an evaluator) to perform mindless evaluation of an arbitrary function, usually represented as a Boolean circuit.

The construction of classic GC mainly includes three stages: encryption, transmission, and evaluation.

First, for each wire in the circuit, the obfuscator generates two random strings as labels, representing the two possible bit values "0" and "1" for that wire, respectively. For each gate in the circuit, the obfuscator creates a truth table. Each output of the truth table is encrypted with the two labels corresponding to its input. It is up to the obfuscator to choose a key derivation function that uses these two labels to generate a symmetric key.

The obfuscator then wraps the rows of the truth table. After the obfuscation phase is over, the obfuscator passes the obfuscated table and the input line labels corresponding to its input to the evaluator.

Furthermore, evaluators securely obtain labels corresponding to their inputs via oblivious transfer (Oblivious Transfer [13, 14, 15]). With the obfuscation table and the labels of the input lines, the evaluator is responsible for repeatedly decrypting the obfuscation table until the final result of the function is obtained.

▲ Secret Sharing (SS)

The GMW protocol is the first secure multi-party computation protocol that allows any number of parties to safely compute a function that can be expressed as a Boolean circuit or an arithmetic circuit. Taking a Boolean circuit as an example, all parties use an XOR-based SS scheme to share the input, and the parties interact to calculate the results, gate by gate. The protocol based on GMW does not need to confuse the truth table, but only needs to perform XOR and AND operations for calculation, so it does not need to perform symmetrical encryption and decryption operations. Furthermore, GMW-based protocols allow precomputation of all cryptographic operations, but require multiple rounds of interactions between multiple parties during the online phase. Therefore, GMW achieves good performance in low-latency networks.

The BGW protocol is a secure multi-party computing protocol for arithmetic circuits with more than three parties. The overall structure of the agreement is similar to GMW. In general, BGW can be used to compute any arithmetic circuit. Similar to the GMW protocol, for the addition gate in the circuit, the calculation can be performed locally, while for the multiplication gate, all parties need to interact. However, GMW and BGW differ in the form of interaction. Instead of using OT for communication between parties, BGW relies on linear SS (such as Shamir's SS) to support multiplication. But BGW relies on honest-majority. The BGW protocol can fight against the removal of t

SPDZ is a dishonest majority computing protocol proposed by Damgard et al., which can support computing arithmetic circuits with more than two parties. It is divided into offline phase and online phase. The advantage of SPDZ is that expensive public-key cryptographic computations can be done in the offline phase, while the online phase purely uses cheap, information-theoretically secure primitives. SWHE is used to perform constant-round secure multiplication in the offline phase. The online phase of SPDZ is linear-round, follows the GMW paradigm, and uses secret sharing over finite fields to ensure security. SPDZ can fight against t<=n corrupt parties of malicious opponents at most, where t is the number of opponents and n is the number of computing parties.

The centralized cryptography protocol will be summarized in stages, and the framework differences corresponding to different technical routes are roughly as follows:

Federated Learning 3.0 -- Swarm Learning

In 2021, Joachim Schultze of the University of Bonn and his partners proposed a "decentralized machine learning system" called Swarm Learning (group learning), which is a further evolution and upgrade based on MPL, which replaces the current inter-institutional A way to centralize data sharing in medical research. Swarm Learning shares parameters through the Swarm network, builds models independently on the local data of each participant, and uses blockchain technology to take strong measures against dishonest participants who try to destroy the Swarm network.

Compared with FL and MPL, Swarm Learning introduces the blockchain technology into the training process of federated learning, and replaces the trusted third party with the blockchain to play a role in training synergy.

【Summary and Prospect】▲ Comparison of Federated Learning Technology Routes

Throughout the past and present of federated learning, it already has a variety of technical routes to solve problems. After summary, distributed machine learning (DML), federated learning (FL), secure multi-party learning (MPL), group learning (SL) The differences are broadly as follows:

Among them, we make a deeper comparison between traditional FL and MPL, which is reflected in the following six points:

1) Privacy protection

The MPC protocol used in the MPC framework provides high security guarantees for both parties. However, the non-encrypted FL framework exchanges model parameters between the data owner and the server in plain text, and sensitive information may also be leaked;

2) Communication method

In MPL, communication between data owners is usually in the form of peer-to-peer without a trusted third party, while FL is usually in the form of Client-Server with a centralized server. In other words, each data owner in MPL is equal in state, while the data owner and centralized server in FL are not equal;

3) Communication overhead

For FL, since the communication between data owners can be coordinated by a centralized server, the communication overhead is smaller than the point-to-point form of MPL, especially when the number of data owners is very large;

4) Data format

Currently, non-IID settings are not considered in MPL's solution. However, in FL's solution, since each data owner trains the model locally, it is easier to adapt to non-IID settings;

5) Accuracy of training model

In MPL, there is usually no loss of precision in the global model. But if FL utilizes DP to protect privacy, the global model usually suffers a certain accuracy loss;

6) Application scenarios

Combined with the above analysis, it can be found that MPL is more suitable for scenarios with higher security and accuracy, while FL is more suitable for scenarios with higher performance requirements and is used for more data owners.

▲ Multi-party comparison of the federated learning framework

Content comparison of FL basic framework since 2016

Content comparison of FL-based MPL basic framework

With the continuous development of federated learning technology, federated learning platforms for different challenges are emerging, but they have not yet reached a mature stage. At present, in academia, the federated learning platform mainly solves the problem of unbalanced and non-uniformly distributed data, while the industry focuses more on cryptographic protocols to solve the security problems of federated learning.

Both sides go hand in hand, and many existing machine learning algorithms have been federalized, but they are still immature and have not yet reached the stage where they can be put into production. In recent years, the research and implementation of the federated learning framework is still in its infancy, requiring continuous efforts and advancement.

About the Author

Yan Yang Federal Learning Trailblazer

references

references

[1] P. Voigt and A. Von dem Bussche, “The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr),” A Practical Guide, 1st Ed., Cham: Springer Inter- national Publishing, 2017.

[2] D. Bogdanov, S. Laur, and J. Willemson, “Sharemind: A framework for fast privacy-preserving computations,” in Proceedings of European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, 2008, pp. 192–206.

[3] D. Demmler, T. Schneider, and M. Zohner, “Aby-a framework for efficient mixed-protocol secure two-party computation.” in Proceedings of The Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, 2015.

[4] P. Mohassel and Y. Zhang, “Secureml: A system for scalable privacy- preserving machine learning,” in Proceedings of 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 19–38.

[5] H. B. McMahan, E. Moore, D. Ramage, and B. A. y Arcas, “Feder- ated learning of deep networks using model averaging,” CoRR, vol. abs/1602.05629, 2016.

[6] J. Konecˇny`, H. B. McMahan, D. Ramage, and P. Richta ́rik, “Federated optimization: Distributed machine learning for on-device intelligence,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.02527, 2016.

[7] J. Konecˇny`, H. B. McMahan, F. X. Yu, P. Richta ́rik, A. T. Suresh, and D. Bacon, “Federated learning: Strategies for improving communica- tion efficiency,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.05492, 2016.

[8] B. McMahan, E. Moore, D. Ramage, S. Hampson, and B. A. y Arcas, “Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentral- ized data,” in Proceedings of Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 2017, pp. 1273–1282.

[9] A. C.-C. Yao, “How to generate and exchange secrets,” in Proceedings of the 27th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (sfcs 1986). IEEE, 1986, pp. 162–167.

[10] V. Smith, C.-K. Chiang, M. Sanjabi, and A. S. Talwalkar, “Federated multi-task learning,” in Proceedings of Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, pp. 4424–4434.

[11] R. Fakoor, F. Ladhak, A. Nazi, and M. Huber, “Using deep learning to enhance cancer diagnosis and classification,” in Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, vol. 28. ACM New York, USA, 2013.

[12] M. Rastegari, V. Ordonez, J. Redmon, and A. Farhadi, “Xnor-net: Imagenet classification using binary convolutional neural networks,” in Proceedings of European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 525–542.

[13] F. Schroff, D. Kalenichenko, and J. Philbin, “Facenet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 815–823.

[14] P. Voigt and A. Von dem Bussche, “The eu general data protection regulation (gdpr),” A Practical Guide, 1st Ed., Cham: Springer Inter- national Publishing, 2017.

[15] D. Bogdanov, S. Laur, and J. Willemson, “Sharemind: A framework for fast privacy-preserving computations,” in Proceedings of European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer, 2008, pp. 192–206.

[16] T.NishioandR.Yonetani,“Clientselectionforfederatedlearningwith heterogeneous resources in mobile edge,” in Proceedings of 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–7.

[17] P. P. Liang, T. Liu, L. Ziyin, R. Salakhutdinov, and L.-P. Morency, “Think locally, act globally: Federated learning with local and global representations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.01523, 2020.

[18] Y. Liu, Y. Kang, X. Zhang, L. Li, Y. Cheng, T. Chen, M. Hong, and Q. Yang, “A communication efficient vertical federated learning framework,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.11187, 2019.

[19] K. Bonawitz, V. Ivanov, B. Kreuter, A. Marcedone, H. B. McMahan, S. Patel, D. Ramage, A. Segal, and K. Seth, “Practical secure aggre- gation for privacy-preserving machine learning,” in Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2017, pp. 1175–1191.

[20] K. Cheng, T. Fan, Y. Jin, Y. Liu, T. Chen, and Q. Yang, “Se- cureboost: A lossless federated learning framework,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.08755, 2019.

[21] G. Xu, H. Li, S. Liu, K. Yang, and X. Lin, “Verifynet: Secure and verifiable federated learning,” IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 15, pp. 911–926, 2019.

[22] H. B. McMahan, D. Ramage, K. Talwar, and L. Zhang, “Learn- ing differentially private recurrent language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.06963, 2017.

[23] Y. Zhao, J. Zhao, M. Yang, T. Wang, N. Wang, L. Lyu, D. Niyato, and K. Y. Lam, “Local differential privacy based federated learning for internet of things,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.08856, 2020.

[24] M. Hastings, B. Hemenway, D. Noble, and S. Zdancewic, “Sok: General purpose compilers for secure multi-party computation,” in Proceedings of 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1220–1237.

[25] I. Giacomelli, S. Jha, M. Joye, C. D. Page, and K. Yoon, “Privacy-

preserving ridge regression with only linearly-homomorphic encryp- tion,” in Proceedings of 2018 International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security. Springer, 2018, pp. 243–261.

[26] A. Gasco ́n, P. Schoppmann, B. Balle, M. Raykova, J. Doerner, S. Zahur, and D. Evans, “Privacy-preserving distributed linear regression on high- dimensional data,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, vol. 2017, no. 4, pp. 345–364, 2017.

[27] S. Wagh, D. Gupta, and N. Chandran, “Securenn: 3-party secure computation for neural network training,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, vol. 2019, no. 3, pp. 26–49, 2019.

[28] M. Byali, H. Chaudhari, A. Patra, and A. Suresh, “Flash: fast and robust framework for privacy-preserving machine learning,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, vol. 2020, no. 2, pp. 459–480, 2020.

[29] S. Wagh, S. Tople, F. Benhamouda, E. Kushilevitz, P. Mittal, and T. Rabin, “Falcon: Honest-majority maliciously secure framework for private deep learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.02229, 2020.

[30] V. Nikolaenko, U. Weinsberg, S. Ioannidis, M. Joye, D. Boneh, and N. Taft, “Privacy-preserving ridge regression on hundreds of millions of records,” pp. 334–348, 2013.

[31] M. Chase, R. Gilad-Bachrach, K. Laine, K. E. Lauter, and P. Rindal, “Private collaborative neural network learning.” IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch., vol. 2017, p. 762, 2017.

[32] M. S. Riazi, C. Weinert, O. Tkachenko, E. M. Songhori, T. Schneider, and F. Koushanfar, “Chameleon: A hybrid secure computation frame- work for machine learning applications,” in Proceedings of the 2018 on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2018, pp. 707–721.

[33] P. Mohassel and P. Rindal, “Aby3: A mixed protocol framework for machine learning,” in Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2018, pp. 35– 52.

[34] N. Agrawal, A. Shahin Shamsabadi, M. J. Kusner, and A. Gasco ́n, “Quotient: two-party secure neural network training and prediction,” in Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2019, pp. 1231–1247.

[35] R. Rachuri and A. Suresh, “Trident: Efficient 4pc framework for pri- vacy preserving machine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.02631, 2019.

[36] A. Patra and A. Suresh, “Blaze: Blazing fast privacy-preserving ma- chine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09042, 2020.

[37] Song L, Wu H, Ruan W, et al. SoK: Training machine learning models over multiple sources with privacy preservation[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.03386, 2020.