a16z Partner's Personal Account: Boutique VC is Dead, Scaling Up is the Ultimate Endgame for VC

- Core Viewpoint: The venture capital industry is experiencing a paradigm shift from being "judgment-driven" to "deal-winning capability-driven." As software and AI become the core of the economy, capital-intensive startups of unprecedented scale are emerging. Only "mega-institutions" with scaled platforms that can provide founders with comprehensive support will prevail in future competition.

- Key Elements:

- Massive Market Change: Software is now a pillar of the U.S. economy, and AI is accelerating development. The growth ceiling for top startups (like OpenAI, SpaceX) has risen to the trillion-dollar level, and they are mostly capital-intensive.

- Founder Needs Have Upgraded: Companies are staying private longer, and competition is fiercer. Founders need VCs to provide far more than just capital—they need comprehensive services (recruiting, go-to-market strategy, networks, etc.) to help them win.

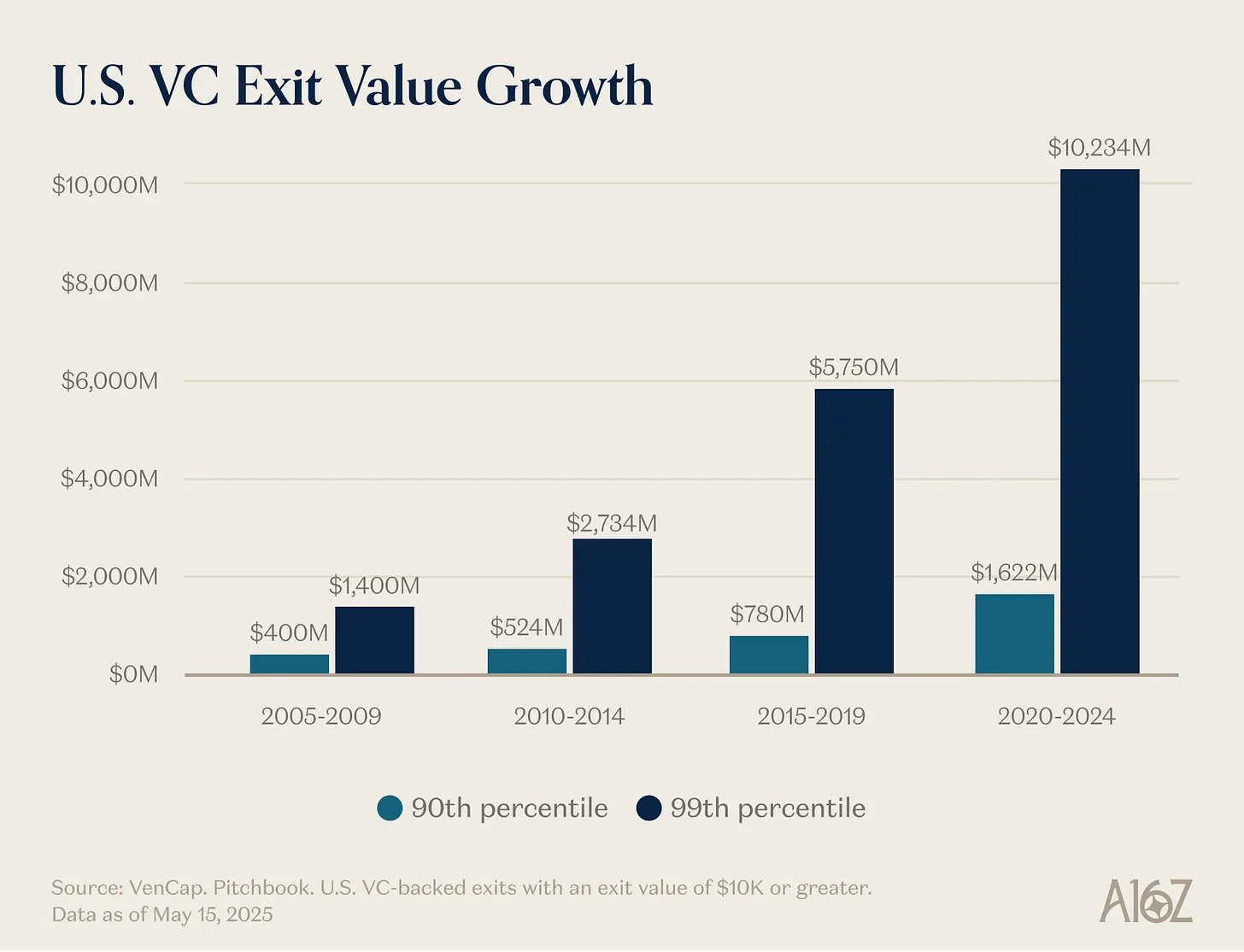

- VC Industry Scaling is Rational: The funding amounts required by top private companies far exceed those of the past. The VC industry must scale to meet this demand, and top scaled institutions have consistently achieved extremely high return multiples.

- Shift in Competitive Core: The number of VC firms has surged. The ability to win top deals has become as important as, if not more important than, the ability to pick them. Firms need to build compounding competitive advantages (like networks, service platforms) to gain access to deals.

- Industry Structure Evolution: The future VC industry will take on a "barbell shape," with a few ultra-large-scale players on one end and numerous small, specialized firms on the other. Funds in the middle will face difficulties.

Original Author: Erik Torenberg

Original Compilation: Odaily

Introduction: In the traditional narrative of venture capital (VC), the "boutique" model is often praised, with the belief that scaling leads to a loss of soul. However, a16z partner Erik Torenberg presents a counterpoint in this article: with software becoming the backbone of the U.S. economy and the advent of the AI era, the demands of startups for capital and services have undergone a qualitative shift.

He argues that the VC industry is undergoing a paradigm shift from being "judgment-driven" to being "deal-winning capability-driven." Only "mega-firms" like a16z, which possess scaled platforms and can provide founders with comprehensive support, can prevail in the trillion-dollar game.

This is not just an evolution of the model; it is the self-evolution of the VC industry under the wave of "software eating the world."

Full text as follows:

In classical Greek literature, there is a meta-narrative above all others: respect for the gods versus hubris. Icarus was burned by the sun not fundamentally because he was too ambitious, but because he did not respect the divine order. A more recent example is professional wrestling. You can tell who is the face and who is the heel simply by asking, "Who is respecting the business, and who is disrespecting it?" All good stories take one form or another of this.

Venture capital (VC) has its own version of this story. It goes like this: "VC was, and always has been, a boutique business. Those big firms have gotten too big, aiming too high. Their downfall is inevitable because what they're doing is simply disrespectful to the game."

I understand why people want this story to be true. But the reality is, the world has changed, and venture capital has changed with it.

There is more software, more leverage, and more opportunity than before. There are more founders building bigger companies than before. Companies are staying private longer than before. And founders are demanding more from VCs than before. Today, the founders building the best companies need partners who can truly roll up their sleeves and help them win, not just write checks and wait for outcomes.

Therefore, the primary goal for a venture firm now is to create the best interface for helping founders win. Everything else—how to staff, how to deploy capital, what size fund to raise, how to assist with deals, and how to allocate power for founders—flows from that.

Mike Maples famously said: your fund size is your strategy. It's also true that your fund size is your belief about the future. It's your bet on the size of startup outcomes. Raising huge funds over the past decade might have been seen as "hubris," but that belief was fundamentally correct. So, when top firms continue to raise massive funds to deploy over the next decade, they are betting on the future and putting their money where their mouth is. Scaled Venture is not a corruption of the venture model: it's the venture model finally maturing and adopting the characteristics of the companies it backs.

Yes, Venture Firms Are an Asset Class

In a recent podcast, legendary Sequoia investor Roelof Botha made three points. First, despite the scaling of venture, the number of companies that "win" each year is fixed. Second, the scaling of the venture industry means too much money chasing too few good companies—therefore venture cannot scale, it's not an asset class. Third, the venture industry should shrink to match the actual number of winning companies.

Roelof is one of the greatest investors of all time, and he's a great guy. But I disagree with him here. (It's worth noting, of course, that Sequoia has also scaled: it's one of the largest VC firms globally.)

His first point—that the number of winners is fixed—is easily disproven. There used to be about 15 companies reaching $100 million in revenue per year; now there are about 150. Not only are there more winners than before, but the winners are also bigger than before. While entry prices are higher, the outcomes are much larger than before. The ceiling for startup growth has gone from $1 billion to $10 billion, and now to $1 trillion and beyond. In the 2000s and early 2010s, YouTube and Instagram were considered massive $1 billion acquisitions: valuations so rare back then that we called companies valued at $1 billion or more "Unicorns." Now, we simply assume OpenAI and SpaceX will be trillion-dollar companies, with several more to follow.

Software is no longer a fringe sector of the U.S. economy made up of weird, misfit people. Software now *is* the U.S. economy. Our biggest companies, our national champions, are no longer General Electric and ExxonMobil: they are Google, Amazon, and Nvidia. Private tech companies account for 22% of the S&P 500. Software hasn't finished eating the world—in fact, with the acceleration from AI, it's just getting started—and it's more important than it was fifteen, ten, or five years ago. Therefore, the scale a successful software company can achieve is greater than before.

The definition of a "software company" has also changed. Capital expenditures have skyrocketed—large AI labs are becoming infrastructure companies with their own data centers, power generation, and chip supply chains. Just as every company became a software company, now every company is becoming an AI company, and perhaps an infrastructure company too. More companies are moving into the world of atoms. Boundaries are blurring. Companies are vertically integrating aggressively, and the market potential for these vertically integrated tech giants is far greater than anyone imagined for pure software companies.

This leads to why the second point—too much money chasing too few companies—is wrong. The outcomes are much larger, the software world is more competitive, and companies are going public much later than before. All of this means great companies simply need to raise much more money than before. Venture capital exists to invest in new markets. What we've learned time and again is that new markets are always, in the long run, much larger than we expect. The private markets are mature enough to support top companies at unprecedented scale—look at the liquidity available to top private companies today—and both private and public market investors now believe the scale of venture outcomes will be staggering. We have consistently underestimated how large venture capital as an asset class can and should be, and venture is scaling to catch up to that reality, and to the opportunity set. The new world needs flying cars, global satellite grids, abundant energy, and intelligence so cheap it's not worth metering.

The reality is, many of the best companies today are capital-intensive. OpenAI needs to spend billions on GPUs—more compute infrastructure than anyone imagined possible. Periodic Labs needs to build automated labs at an unprecedented scale for scientific innovation. Anduril needs to build the future of defense. And all of these companies need to hire and retain the best talent in the world in the most competitive talent market in history. The new generation of big winners—OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, Anduril, Waymo, etc.—are capital-intensive and have raised massive initial rounds at high valuations.

Modern tech companies often require hundreds of millions of dollars because the infrastructure needed to build world-changing, cutting-edge technology is simply that expensive. In the dot-com era, a "startup" entered an empty field, anticipating demand from consumers still waiting for dial-up. Today, startups enter an economy shaped by three decades of tech giants. Supporting "Little Tech" means you have to be prepared to arm David against a handful of Goliaths. Companies in 2021 did get overfunded, with a large portion going to sales and marketing to sell products that weren't 10x better. But today, money is going to R&D or capex.

Therefore, winners are far larger than before and need to raise much more money than before, often from the very beginning. So, the venture industry must, by necessity, become much larger to meet that demand. This scaling is justified given the size of the opportunity set. If VC scale were too large for the opportunities VCs invest in, we should have seen the largest firms underperform. But we simply haven't seen that. While scaling, top venture firms have repeatedly delivered extremely high multiples—as have the LPs who can get into these firms. A famous venture capitalist once said a $1 billion fund could never return 3x: it was too big. Since then, certain firms have returned over 10x on a $1B fund. Some point to underperforming firms to indict the asset class, but any power-law industry will have massive winners and a long tail of losers. The ability to win deals without competing on price is what allows firms to sustain returns. In other major asset classes, people sell products to or lend to the highest bidder. But VC is the quintessential asset class that competes on dimensions other than price. VC is the only asset class with significant persistence in the top 10%.

The final point—that the venture industry should shrink—is also wrong. Or, at least, it would be bad for the tech ecosystem, for the goal of creating more generational tech companies, and ultimately for the world. Some complain about the second-order effects of more venture capital (and there are some!), but it also comes with a massive increase in startup market cap. Advocating for a smaller venture ecosystem is likely also advocating for smaller startup market caps, and the result would likely be slower economic growth. This perhaps explains why Garry Tan said in a recent podcast: "Venture capital can and should be 10x bigger than it is today." Admittedly, it might be good for an individual LP or GP if there were no more competition and they were the "only game in town." But it's clearly better for founders, and for the world, if there is more venture capital than there is today.

To elaborate on this further, let's consider a thought experiment. First, do you think there should be many more founders in the world than there are today?

Second, if we suddenly had many more founders, what kind of firm would best serve them?

We won't spend too much time on the first question because if you're reading this, you probably know we think the answer is obviously yes. We don't need to tell you too much about why founders are so great and so important. Great founders create great companies. Great companies create new products that improve the world, organize and direct our collective energy and risk appetite towards productive goals, and create a disproportionate share of new enterprise value and interesting jobs in the world. And we are certainly not at an equilibrium where every person capable of founding a great company has already founded one. That's why more venture capital helps unlock more growth from the startup ecosystem.

But the second question is more interesting. If we woke up tomorrow and there were 10x or 100x more entrepreneurs (spoiler: this is happening), what should the world's venture firms look like? How should venture firms evolve in a more competitive world?

To Win Deals, Not Lose Them

Marc Andreessen likes to tell the story of a famous venture capitalist who said the VC game is like a sushi conveyor belt: "A thousand startups come around, you meet them. And then occasionally you reach out and pick a startup off the conveyor belt, and you invest in it."

The kind of VC Marc described—well, that was almost every VC for most of the last few decades. Winning deals was that easy back in the 1990s or 2000s. Because of that, the only skill that really mattered for a great VC was judgment: the ability to tell a good company from a bad one.

There are plenty of VCs who still operate this way—essentially the same way VCs operated in 1995. But the world has shifted dramatically beneath their feet.

Winning deals used to be easy—as easy as picking sushi off a conveyor belt. Now it's extremely hard. People sometimes describe VC as poker: knowing when to pick a company, knowing at what price to get in, etc. But that perhaps obscures the all-out war you have to wage just to get the right to invest in the best companies. Old-school VCs miss the days when they were the "only game in town" and could dictate terms to founders. But now there are thousands of VC firms, and founders have more term sheets than ever. So, more and more of the best deals involve incredibly intense competition.

The paradigm shift is that the ability to win deals is becoming as important as picking the right companies—maybe even more important. What's the point of picking the right deal if you can't get in? A few things have driven this change. First, the proliferation of venture firms means VCs need to compete with each other to win deals. Because there are more companies competing for talent, customers, and market share than ever, the best founders need powerful firm partners to help them win. They need firms with resources, networks, and infrastructure to give their portfolio companies an edge.

Second, because companies are staying private longer, investors can invest later—when companies are more proven, and therefore deals are more competitive—and still get venture-like outcome returns.

The last reason, and the least obvious one, is that picking has gotten slightly easier. The VC market has become more efficient. On one hand, there are more serial entrepreneurs consistently creating iconic companies. If Musk, Sam Altman, Palmer Luckey, or a genius serial entrepreneur starts a company, VCs line up quickly to try to invest. On the other hand, companies are reaching insane scale faster (and have more upside because they stay private longer), so product-market fit (PMF) risk is lower relative to the past. Finally, because there are so many great firms now, it's easier for founders to reach investors, so it's hard to find deals that other firms aren't already pursuing. Picking is still core to the game—picking the right enduring company at the right price—but it's no longer the single most important piece by far.

Ben Horowitz hypothesized that the ability to win repeatedly automatically makes you a top firm: because if you can win, the best deals come to you. Only when you can win any deal do you have the privilege of picking. You might not pick the right one, but at least you have the chance. And of course, if your firm can repeatedly win the best deals, you attract the best pickers to work for you because they want to get into the best companies. (As Martin Casado said when recruiting Matt Bornstein to a16z: "Come here to win deals, not lose deals.") So, the ability to win creates a virtuous cycle that improves your picking ability.

For these reasons, the game has changed. My partner David Haber described the shift venture capital needs to make in response to this change in his essay: