Polymarket's "Hand of God": Frequent Prediction Disputes, the Black Box of Adjudication Power in the "Centralization" Dilemma

- Core Viewpoint: The adjudication dispute on the Polymarket prediction market regarding whether the US "invaded" Venezuela exposes the failure boundary of "code is law" in decentralized prediction markets when dealing with complex real-world events that rely on social consensus and semantic interpretation. The core challenge lies in the inability to define facts in a decentralized manner.

- Key Elements:

- Polymarket ruled that US actions against Venezuela did not constitute an "invasion" under its rules, causing the "Yes" option to be invalid and sparking user protests. This highlights the deviation between semantic definitions and common understanding.

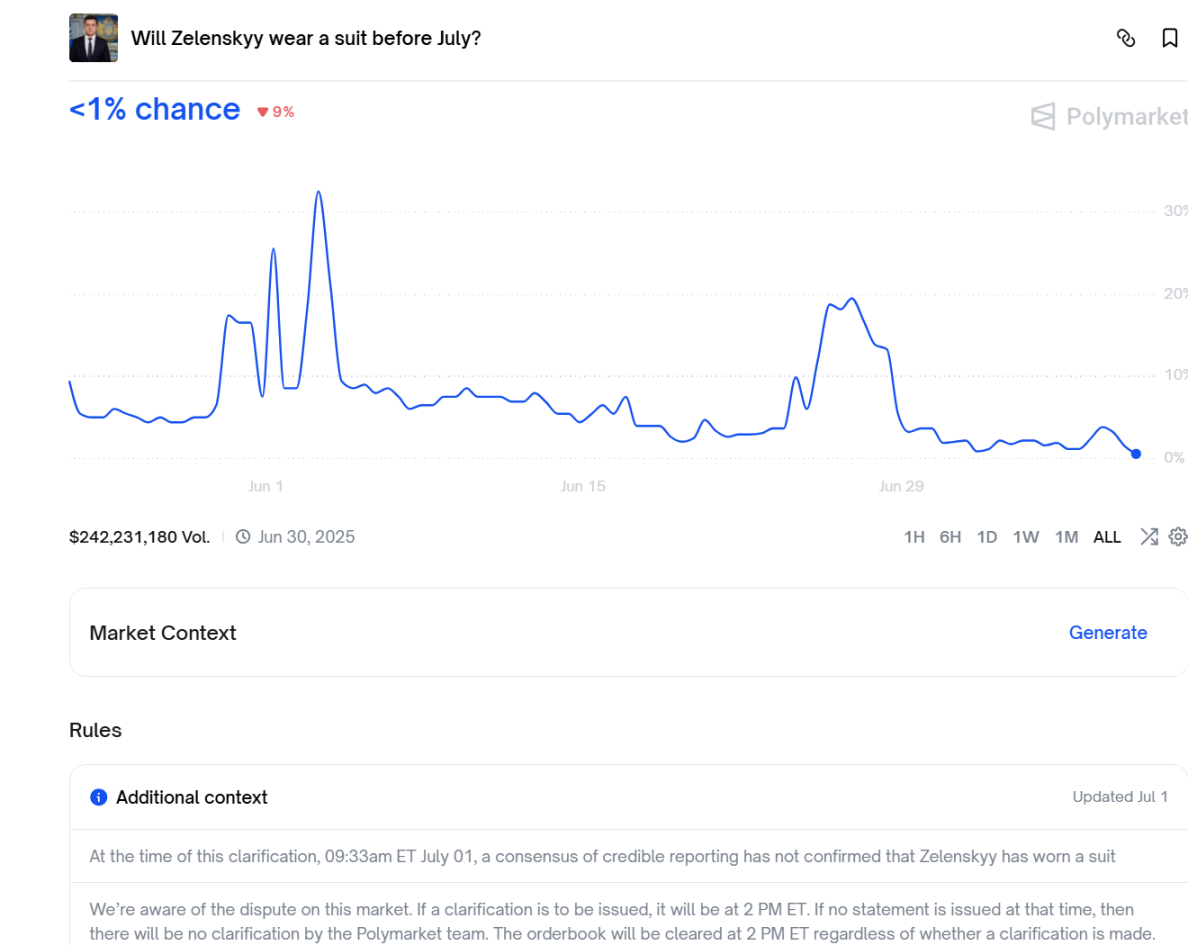

- Similar disputes (e.g., whether Zelenskyy "wore a suit") occur frequently. The root cause is that event adjudication relies on the voting mechanism of decentralized oracles (like UMA), which is susceptible to manipulation by major players through rules, rather than being a technical issue.

- Blockchain excels at handling deterministic states, but prediction market questions (e.g., qualifying wars, political actions) are highly dependent on context and social consensus. Subjectivity is inevitable when translating reality into a settleable outcome.

- The decentralization of prediction markets is mainly reflected in the trading and settlement execution layer. In contrast, the power to define, interpret, and adjudicate events is essentially highly centralized, hidden within the rule-making and interpretation processes.

- This dispute reveals the applicable boundaries of prediction markets: they are suitable for events with clear outcomes and well-defined terms, but are not adept at handling complex real-world problems laden with semantic ambiguity and value judgments.

Whether the United States actually "invaded" Venezuela—this semantic judgment directly determined a bet worth over ten million dollars.

You might find this counterintuitive. After all, in the real world, the US did take a series of actions against Venezuela, including military deployments and direct operations. In everyday language and media narratives, such actions are easily interpreted as an "invasion."

However, the final settlement did not go as some betting users expected. In its final ruling, Polymarket did not acknowledge that the US military's actions constituted an "invasion" within the context of its rules, thereby negating the validity of the "Yes" option and sparking protests from users who had placed bets.

This is actually a not-so-new but highly representative controversy, once again exposing a long-standing yet often overlooked structural issue in prediction markets: When it comes to complex real-world events, what basis does a decentralized prediction market use, and who gets to define the "facts"?

1. The Frequent "Semantic Traps" in Prediction Markets

The reason it's "not so new" is that similar semantic disputes have numerous precedents in prediction markets.

That's right, such situations on Polymarket are already commonplace, especially in predictions surrounding political figures and international situations. The platform has repeatedly produced rulings that users deem "counterintuitive." Some predictions, which are almost uncontroversial in reality, get stuck in repeated appeals and reversals on-chain; for other events, the final ruling results significantly deviate from most users' real-world judgment.

In more extreme cases, during the dispute resolution phase, the oracle mechanism allows token holders to participate in voting. This enables certain topical events to have their conclusions "overturned by the voting power of major players"...

And these controversies share a common characteristic: they are often not technical issues, but issues of social consensus. A widely discussed example is the prediction about whether Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy "wore a suit" at a specific time:

In reality, in June last year, Zelenskyy attended a public event wearing a formal suit. Interpretations from multiple sources, including the BBC and designers, confirmed it was a suit. Logically, the matter should have been settled. But on Polymarket, this seemingly clear fact evolved into a tug-of-war involving hundreds of millions of dollars.

During this period, the probabilities for Yes and No fluctuated wildly, accompanied by high-risk arbitrage. Some achieved massive floating profits in a short time, while the final settlement was repeatedly delayed.

The crux of the issue is that Polymarket relies on the decentralized oracle UMA for result arbitration. Its operational mechanism allows holders to participate in dispute resolution through voting. This makes it easy for major players to manipulate the outcome of certain topical events.

More controversially, the platform level does not deny that this mechanism could be exploited but still insists that "rules are rules," refusing to adjust the arbitration logic post-facto, ultimately allowing large funds to flip the outcome using the rules themselves.

It is precisely such cases that provide a highly representative and clear lens for understanding the institutional boundaries of prediction markets.

2. The Failing Boundary of "Code is Law"

Objectively speaking, prediction markets are now seen as one of the most imaginative applications of blockchain. They are no longer just a small tool for people to "place bets" or "predict the future." Instead, they have become outposts for institutions, analysts, and even central banks to observe market sentiment (Further reading: "The Breakout Moment for 'Prediction Markets': ICE Enters, Hyperliquid Doubles Down, Why Are Giants Competing to 'Price Uncertainty'?").

But all of this has a prerequisite: prediction questions must be answerable unambiguously.

It's important to understand that blockchain systems are inherently good at handling deterministic problems—such as whether assets have arrived, whether a state has changed, or whether a condition has been met. Once these results are written on-chain, there is almost no room for tampering.

However, what prediction markets often face are another type of object: whether a war has broken out, whether an election has ended, whether a certain political or military action constitutes a judgment of a specific nature. These questions are not inherently codifiable. They are highly dependent on context, interpretation, and social consensus, rather than a single, verifiable objective signal.

This is also why, regardless of the oracle or arbitration mechanism used, subjectivity is almost inevitable in the process of transforming real-world events into settleable results.

This is why, in multiple Polymarket controversies, the disagreement between users and the platform is not about whether the facts exist, but about which interpretation of reality is the one that can be settled.

Ultimately, when this interpretive power cannot be fully formalized by code, the underlying logic of the grand vision of "code is law" inevitably encounters its boundary in the face of complex social semantics.

3. The "Last Mile" of Truth is Hard to Decentralize

In many decentralization narratives, "centralization" is often seen as a system flaw. But the author believes that in the specific context of prediction markets, the opposite is true.

This is because prediction markets do not eliminate arbitration power; they merely transfer it from one position to another:

- Trading and Settlement Phase: Highly decentralized, automated execution;

- Definition and Interpretation Phase: Highly centralized, reliant on rules and arbitrators;

In other words, decentralization solves the issue of execution credibility but cannot avoid the reality of concentrated interpretive power. This is also why the concept of "code is law," which is highly attractive in the blockchain world, often seems inadequate in prediction markets—because code cannot generate social consensus on its own; it can only faithfully execute predetermined rules.

And when the rules themselves cannot cover the full complexity of reality, the power of arbitration inevitably returns to "human" hands. The only difference is that this arbitration power no longer appears in the explicit form of an arbitrator but is hidden within the problem definition, rule interpretation, and arbitration process.

Returning to the Polymarket controversy itself, it does not mean prediction markets have failed, nor does it mean the decentralization narrative is a castle in the air. On the contrary, such controversies remind us to re-understand the applicable boundaries of prediction markets: They are very suitable for data/events with clear outcomes and unambiguous definitions but are inherently ill-suited for handling highly politicized, semantically ambiguous, value-judgment-intensive real-world problems.

From this perspective, prediction markets never solve "who is right or wrong." Instead, they address how the market efficiently aggregates expectations under given rules. Therefore, once the rules themselves become the focus of controversy, the system exposes its institutional boundaries.

Like the latest controversy over whether Venezuela was "invaded," it essentially illustrates that when dealing with complex real-world events, decentralization does not mean there is no arbitrator. Rather, the power of arbitration exists in a more concealed form.

For ordinary users, what truly matters might not be whether a prediction market "is decentralized," but rather: When a dispute occurs, who has the power to define the problem? Who decides which version of reality can be settled? Are the rules clear and predictable enough?

In this sense, prediction markets are not just an experiment in collective wisdom; they are also a power game about "who has the right to define reality."

Only by understanding this can we find that balance point closer to certainty amidst uncertain truths.