IOSG Ventures:详解OEV的来源、工作原理与相关协议

Original author: Joey Shin, IOSG Ventures

Let's imagine what the world of every financial action is, it's not just a simple transaction.

This is a complex world made up of information, value, and opportunities, guided by the "invisible hand" of blockchain oracles. In the vibrant world of DeFi, there is something worth paying special attention to, called Oracle Extractable Value (OEV). This is a special value that can be captured due to the way blockchain oracles update prices - or sometimes don't update prices. This article will take you deep into OEV, explore its origins, how it works, and how people cleverly extract value from the tiny differences between real-world prices and their updates on underlying chains/protocols.

But the narrative of OEV is not just that. We should also pay attention to innovative platforms like Uma Oval. They are researching how to make the task of finding OEV beneficial for everyone in DeFi, rather than just a few. Through an in-depth exploration of the complexity of OEV and emerging solutions like Uma Oval, I have summarized some thoughts and feelings about the OEV field to present them.

TL;DR

OEV definition: OEV occurs when there is a gap between the prices of real-world assets and their (lagging) updates on the blockchain, providing profitable opportunities for searchers who act after this oracle update.

Overview of Uma Oval: Uma's Oval adopts a novel approach to manage OEV by allowing searchers to bid on price feeds using wrapped Chainlink oracle updates. It is then sent to MEV-Share to facilitate a private order auction process, and eventually returns value to the protocol.

Key challenges for Oval: Oval is built on a complex and delicate incentive balance between different entities involved in the typical MEV category. However, Oval will need to test and improve some factors on the ground, including potential price latency, specific trust assumptions associated with centralization, and other low-level parameter settings.

Theory behind solving OEV: My analysis suggests that while the existence of OEV presents challenges, innovative solutions like Uma Oval can mitigate its negative impacts and provide a blueprint for a fairer and more sustainable future of DeFi.

Personal insights into the future of DeFi: I advocate for the development and implementation of mechanism design solutions that combine protocol layer and infrastructure layer to promote a healthier ecosystem and a more reasonable MEV game theory model.

OEV Beginner's Guide

What exactly is OEV?

An Oracle Extractable Value (OEV) refers to the maximum extractable value that arises from the lack of or delayed updates of an oracle feed. Oracles provide external data, such as asset prices, to blockchain contracts. However, these updates are discrete rather than continuous, creating information asymmetry and opportunities for Miner Extractable Value (MEV), also known as OEV. This allows search bots to profit from temporary discrepancies between on-chain prices and real-world spot prices before oracle updates occur.

It is important to note that this is not only applicable to operations initiated by oracles. For example, there can be "internal oracle updates" if a significant trade occurs on a DEX like Uniswap and substantially changes the price.

Common OEV strategies include front-running, where searchers monitor pending transactions and insert higher-fee transactions before scheduled trades to profit from price differences during the latency period; arbitrage, where arbitrageurs exploit lagging oracle prices to trade across assets before updates and then sell to secure guaranteed profits; and liquidation, where searchers can identify undercollateralized positions based on price fluctuations and quickly liquidate them for bonuses.

OEV represents the profits captured by exploiting the discreteness of oracle price feeds. Search bots are able to extract value without contributing value to the protocol. This value is attributed to profit-seeking searchers, builders incentivized by including large trades in blocks, and validators who subsequently propose the blocks. However, this comes at the expense of protocol users who face significant liquidation penalties and loss of arbitrage opportunities.

What are the negative impacts of OEV and why should we care?

OEV can have adverse effects on DApps and harm end-users. Overuse of bots to exploit oracle arbitrage and liquidation increases overall transaction costs as these bots consistently bid higher than legitimate trades to secure priority inclusion in blocks. This directly increases gas fees for actual users.

In addition, externally initiated arbitrage trades triggered by temporary discrepancies in oracle prices reduce the profits for liquidity providers in these DeFi ecosystems. Even if the current spot prices offer significant spreads, they are forced to accept lower-profit prices. Over time, continued trading loss on one side of an asset increases the permanent loss for liquidity pools/providers. Users attempting to exchange assets also have to deal with degraded user experiences, such as delayed transaction executions, significantly increased slippage, and greater losses in forced liquidations.

Several common examples briefly illustrate how OEV activities contribute to these issues:

Liquidation: MEV bots actively monitor decentralized lending platforms and swiftly liquidate any undercollateralized loan positions to capture bonus payments from this activity. This relies on liquidating loans before data inconsistencies exposing favorable liquidation trades are resolved with oracle updates.

Arbitrage: The robot continuously trades against lagging oracle prices on one DeFi platform and immediately sells the acquired assets on another platform that may already reflect the current spot pricing. This repetitive arbitrage extracts value without providing meaningful trading volume or liquidity to the affected applications.

Front-running: To maximize profits from predictable oracle events, MEV robots insert high fee orders, timed to execute before expected user transactions. By confirming their extraction transactions within a short delay window before major pricing updates, robots exploit differentials before competitive trades from actual users.

However, more troubling is that robots extract value without engaging in any mutually beneficial interaction or supporting the underlying DeFi protocols. They leverage temporary oracle inaccuracies without actually trading or providing liquidity on these platforms, further incentivizing the dominant builder ecosystem. The fees paid by robots are merely to prioritize their transactions, exacerbating block space competition and fostering infrastructure centralization instead of benefiting end users or applications.

Overall, a significant amount of value accumulates to oracle hunters and major blockchain validators instead of flowing back to nurture ecosystem growth or sustainability. Draining income lifelines to external actors seeking one-sided profits severely impacts the growth trajectory of decentralized finance. Transferring the captured extractable value of oracles to value-generating applications offers a path to transform the core economic sustainability of DeFi.

What is Order Flow Auction?

Order Flow Auctions (OFAs) aggregate swap intent and trades and rank them according to fairness criteria. This model aims to minimize the negative effects of MEV strategies.

OFAs allow traders to easily publish their desired swap intent, which is then filled by competing external parties. This provides traders with the best prices across various decentralized and centralized liquidity venues without the need to manually search for optimal rates.

In the OFA structure, swappers simply publish their trade intent, and specialized fillers optimize and execute the trades from various liquidity sources. These liquidity sources include automated market makers, private liquidity pools, etc., which fillers can leverage to meet the swapping demand.

Fillers actively compete to provide the most favorable transaction fees to initial swappers. Their profit comes from the price differential between the actual execution price and the exchange rate provided to the intent-trading swappers.

The main benefits of trading using OFA include reducing the negative externality of MEV by attempting fair trade ordering, providing better prices and overall efficiency for initial traders, simplifying decentralized trading across liquidity sources, and batch trading for improved execution efficiency.

By outsourcing order execution to competitive fillers, the OFA structure simplifies the process of swapping in complex liquidity landscapes while providing consistently favorable pricing for traders.

Protocol Examples for Addressing OEV

API 3

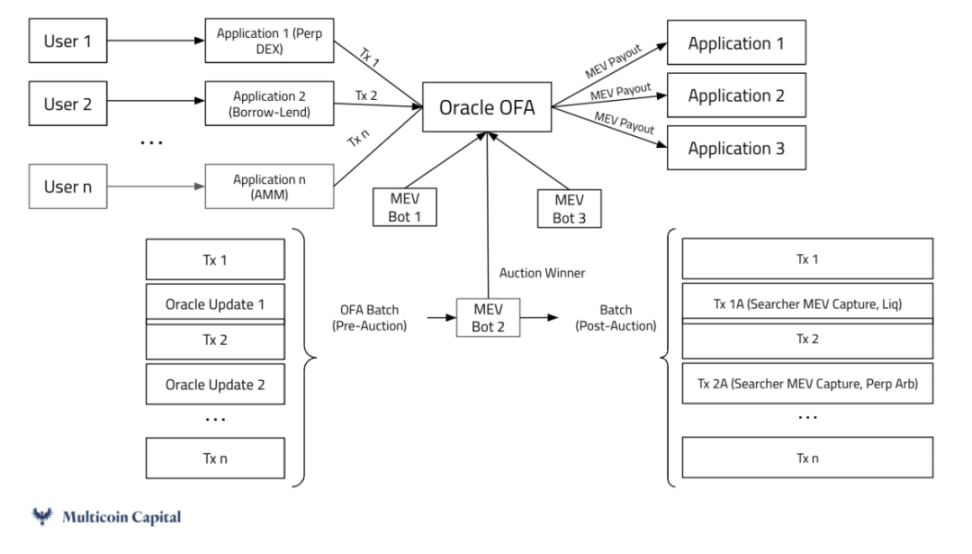

API 3 solves the problems surrounding OEV by implementing a specific oracle-focused OFA mechanism called OEV-Share, which is groundbreaking. It allows searchers to bid for exclusive rights to execute API 3 data source updates from first-party oracles off-chain, owned and operated by API providers themselves, and capture OEV profits associated with these transactions. The metatransactions cryptographically signed by API 3 oracles enable winning bidders to perform data source updates.

API 3 introduces a competition-based OEV auction into the existing oracle infrastructure, bringing several key benefits:

The auction maximizes the efficiency of value extraction by linking oracle events to incentives.

Secondly, the model prevents value from leaking out of the network by returning the proceeds to affected dApps instead of external accumulation.

Thirdly, the competitive pressure in the auction naturally reduces costs and increases the timeliness of updates. This enables API 3 to provide cheap, accurate, low-latency data sources at scale, which is a cornerstone of DeFi's further adoption.

Zooming out, API 3's OEV architecture creates a mutually beneficial sustainable closed-loop model: search bots gain a pathway to extract OEV profits, dApps receive new revenue streams while paying lower fees for critical oracle services, and API 3 itself benefits from a profitable model that sustains oracle infrastructure development and operation.

How is this achieved under the current "balanced" (though not entirely balanced, as it introduces negative externalities, but the interactions of different entities in the MEV architecture are somewhat fixed) MEV incentive mechanism?

Searchers gain an organized pathway, capturing overlooked OEV opportunities beyond transaction-level MEV. While employing a structured bidding process may introduce slight programmatic friction, the improvement in efficiency and reduction in competition will ultimately boost income. Since updates will be designated to specific searchers for execution, it will be compatible with any block generation and validation scheme - for example, it does not need a private mempool. Then, the auction proceeds will be allocated back to the protocol, meaning they will realize the profits that could have leaked out otherwise.

Source: Multicoin Capital

Pyth Network is pioneering a new approach to solving OEV (Oracle-enabled-value) with its leadership position in providing first-party financial data in existing markets. Pyth recognizes that proprietary data obtained directly from market makers, liquidity providers, exchanges, and other direct ecosystem participants is more accurate and up-to-date than third-party aggregated pricing.

By accessing these high-quality data feeds, Pyth's oracle is designed to provide pricing information for contracts that require real-world value with significantly higher fidelity and lower latency. Pyth also implements a demand-driven model, allowing contracts to accurately obtain price updates on-demand instead of relying on intermittent push-based delivery. This increases flexibility while reducing network overhead costs.

At the intersection of critical blockchain pricing data and contract execution logic, Pyth appears well-suited to mediate valuable space surrounding the provision of pricing information. Through aggregated access to its oracle information flow by embedded applications, Pyth intends to facilitate global order flow auctions and allocate trading access to dedicated bots. Unlike cases where value strictly accrues externally, Pyth can return contract interaction profits to dApps that utilize it.

For Pyth's neutral oracle network, benefits include generating new revenue streams without compromising its independent position within the ecosystem. By massively integrating access to information flows between networks, fragmented application-specific auctions can be avoided. More competitive pricing captures value more comprehensively in OEV events.

The interaction within the MEV (Miner Extracted Value) ecosystem enables the protocol to have better mechanistic trade-offs than the current OEV lifecycle. The core uniqueness of the Pyth network is the recognition of the oracle's role by establishing proprietary data sharing incentives between first parties and contract platforms. By directly obtaining on-chain prices from market participants, Pyth reinforces reliability by minimizing latency while aligning incentives within the ecosystem between applications consuming data and platforms producing data. Searchers achieve efficiency by organizing access to valuable instances in the blockspace connected to oracles. Builders exchange unlimited profit potential for the privilege of overseeing critical market events. Crucially, Pyth's advantageous position facilitates the redistribution of extracted profits to integrated applications through aggregated data flow auctions, nourishing the ecosystem with revenue growth instead of wasted leakage.

UMA Oval (Oracle Value Aggregator Layer)

Source: https://medium.com/uma-project/announcing-oval-earn-protocol-revenue-by-capturing-oracle-mev-877192c 51 fe 2

Working Principle

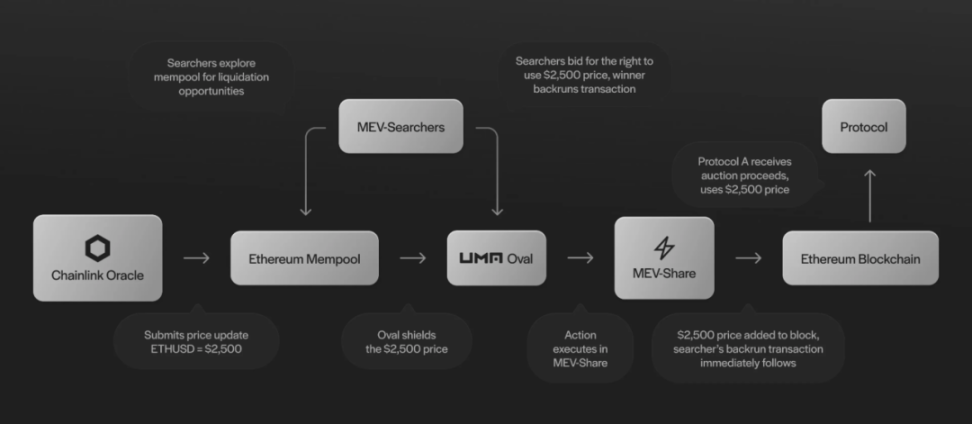

The UMA Oval integrates with Chainlink's existing price feed infrastructure and utilizes Flashbots' MEV-Share architecture to facilitate auctioning of orders around oracle updates.

When Chainlink's price update is submitted to the blockchain, Oval essentially wraps access to the latest data. This allows search bots to bid and compete for the unlocking rights and "pre-run" the price flow transactions, thus taking advantage of the opportunity provided by OEV.

Trusted intermediary nodes, known as Oval nodes, are responsible for verifying the searcher's bids and configuring refund rules for value allocation. They submit unlocking transactions to release the held updates and associated pre-run bids as a bundle through MEV-Share.

MEV-Share operates a standardized private order auction, coordinating across a wider network of Builders and Validators. The winning bidders of the auction include their bundled pre-run transactions along with the unlocked price information, enabling arbitrage or liquidation events.

Then, based on the refund rules set by Oval nodes, a portion of profits is redirected back to the integrated lending platforms and other protocols that have adopted Oval, while also allocating normal amounts to Builders and Validators (which is achieved through an inherent liquidation bonus rate improvement via Oval mechanism). In this way, value is returned to the applications instead of allowing all profits to accumulate to search bots and external validators.

One thing to note is that apart from Builders and the protocol itself, no one else is affected in the current MEV workflow. Searchers use existing technology, making integration seamless, and the fees are reallocated from the Builder's profits back to the protocol - controlled through metadata of bundled transactions. Validators still receive payment for proposing blocks, also coming from Builder's profits, which may result in increased block inclusion delay during high congestion periods (this will be further discussed in the report). However, Builders are incentivized to generate blocks with a stable private order flow through MEV-Share, especially when MEV value is high, resulting in higher fee allocation for inclusion. It also inhibits bad behavior as MEV-Share can blacklist malicious actors from the protocol.

In summary, Oval leverages existing oracles and MEV architecture to access valuable data information flow updates. By controlling the release timing, auctioning can be conducted, and a portion of the generated profits can be returned to the affected applications.

Oval's Trust Assumptions

In the Oval mechanism, there are three core components - the protocol of the integrated system, Oval nodes that control the auction, and the builder/miner involved in transaction ordering and confirmation. This introduces potential trust issues:

The protocol relies on Oval nodes to set accurate refund rules to return value without delaying or reviewing price updates. However, this does not compromise the operation of most protocols using Chainlink. In the worst-case scenario, the protocol may lose the income originally belonging to the builder and result in a delay in price updates.

Oval relies on MEV-Share/Builders to not leak the latest value updates, to not change the searchers' preferences, and to send the correct pre-run payload. However, in the worst-case scenario, this does not compromise the core operation of the protocol. However, the protocol may lose the income originally belonging to the builder and may result in a delay in price updates.

Both Oval and MEV-Share trust that the Builders comply with the bundling rules in the submitted bundles and do not extract transactions to steal profits. Oval selects Builders that users can choose from. From the Builders' perspective, the incentive to profit from OEV is less than the incentive to receive this private auction flow that is banned. Flashbots has thoroughly explored and field-tested this balancing mechanism where the incentive mechanism prevents malicious Builders from stealing MEV profits:

(Github: https://github.com/flashbots/dowg/blob/main/fair-market-principles.md)

The worst-case scenario here is that a specific liquidation unfolds, as happened today, where a builder captures MEV equivalent to the OEV they made today.

While reputation and financial incentives typically enforce good behavior, reliance on intermediaries creates risks. If Oval nodes fail to publish updates or redirect profits, revenue capture will cease, but the core pricing function will continue through Chainlink's underlying information flow.

In summary, Oval leverages existing oracles and MEV architecture to access valuable data information flow updates. By controlling the release timing, search auctions can be performed and a portion of the generated profit is returned to the affected applications.

Potential risk points and counterarguments

A key question is why UMA chooses to adopt an intermediary auction model through Oval instead of directly implementing on-chain Dutch auction methods for liquidation events within the lending protocol. Compared to automated liquidation incentives, Dutch auctions may generate lower and slower profits for the platform. Maximizing speed and reliability is crucial for high-risk scenarios like under-collateralized loans. Leveraging existing MEV architecture helps ensure liquidity in these situations.

Another concern is whether users might attempt to bribe validators to not propose unlocking new data blocks for reviewing price update releases. However, maintaining such an attack across multiple blocks can be costly. Users would have to significantly outbid the existing tips received by the builder and validators to prioritize their transaction packages. Unless extreme circumstances arise, the incentive for revenue maximization still supports inclusion rather than review.

Another risk issue is what prevents Chainlink from building an alternative proprietary MEV capture system around its own feeds instead of integrating with intermediaries like Oval. One mitigating factor is redirecting MEV revenue back to the oracle providers, which can serve as a useful funding mechanism for Chainlink's continued development. Oval provides a validation path to achieve this goal through protocol-level integration.

In addition, the trust assumption is largely mitigated by potential minor price delays - as mentioned earlier, the most likely analysis includes up to 3 blocks. In the normal operation of lending protocols, a price delay of up to 3 blocks is not expected to have any measurable impact. This is different from how price delays affect market trades or faster-growing types of products. When liquidation is required, the inclusion rate for the next block (without delay) is 90%, and for 2 blocks, it is 99%. Uma experts do not believe that this delay would cause large enough price movements to deplete existing liquidation buffers.

Finally, a potential vulnerability is whether the builder responsible for order and transaction confirmations could potentially steal OEV profits by bypassing the auction mechanism rather than respecting it. However, incentive alignment still supports compliance with Oval systems to access private order flow from Flashbots. The risk of reputation impact and being cut off from the entire ecosystem provides strong protection against individual theft, and the potential one-time profits pale in comparison to the ongoing revenue streams obtained from following the rules.

Our thoughts on OEV

OEV - Overall thoughts

Although there are many solutions to address OEV (especially to reintroduce value into the protocol/ecosystem), users are still somewhat negatively affected. Solutions such as Broadcaster Extracted Value (BEV) are attempting to alleviate the pressure of MEV on the user side, which may be an interesting direction to consider in the protocol design of other OFA models. To further mitigate some of the trust assumptions brought by the OFA model, we are pleased to see that new OFA mechanisms can also be implemented at the protocol level.

For example, generalizing OEV as even internal price changes (as introduced in the introduction section) allows the protocol to further reduce negative externalities. Taking Oval as an example, just as wrappers can mediate access to external data oracles events to redistribute value, the protocol can treat these impacted trades as internal data updates.

For example, Uniswap can set a threshold where any trade flow greater than $X must be routed through a wrap system similar to Oval. This would allow Uniswap to auction off access, enabling bots to backrun or arbitrage these specific large trades.

Then, just as Oval returns value from liquidation to lending platforms, this Uniswap implementation can return a portion of the profits impacted by large trades to the Uniswap protocol, liquidity pools, liquidity providers, or even protocol users.

Views on Uma Oval

Although UMA Oval smartly captures and redirects OEV using existing frameworks, the system relies on fragile incentive alignment and trusted intermediaries, introducing security risks.

The Oval nodes and order flow mechanism provide optimizations but open up attack vectors. In the worst-case scenario of intermediary trust or incentive models collapsing, critical data flow delays can still occur, enabling further value extraction related to arbitrage.

However, this approach does mitigate certain negative externalities in the current paradigm. As a temporary solution to enhance sustainability, Oval may bring meaningful revenue to affected applications. Nevertheless, concerns about increased centralization, transparency, and latency persist, and these could become future attack vectors if not thoroughly tested in the field.

All in all, UMA Oval represents an innovative attempt to reclaim value leakage, but it may not fundamentally address all the core incentive problems that enable extraction opportunities. Like any novel cryptographic economic system, these mechanisms require extensive scrutiny, audits, and real-world testing in different operational conditions before evaluating true robustness and resistance to mining.

I am very excited to see Oval shift the discourse and inspire ongoing research as they tackle prominent issues in the OEV space that have not been directly addressed. However, understanding the risks and rewards holistically will be key as adoption considerations unfold.