V God's latest long article: How CEX uses technology to prove its innocence

This article comes from Vitalik ButerinThis article comes from

, compiled by Odaily translator Katie Koo.

This post will discuss the process of trying to bring CEX one step closer to trustless, the limitations of these technologies, and some solutions and more powerful ideas that rely on advanced technologies such as ZK-SNARK.

secondary title

Balance Sheets and Merkle Trees: Traditional Proofs of Solvency

The earliest attempts by exchanges to cryptographically prove that they are not deceiving users go way back. In 2011, MtGox, the largest bitcoin exchange at the time, proved they had funds by sending a transaction transferring 424,242 bitcoins to a pre-announced address. In 2013, discussions began about how to tackle the other side of the problem: proving the total size of customer deposits. If you prove that the customer's deposit is equal to X (proof of liability), and prove that you have the private keys for X tokens (proof of asset), then you have a proof of solvency - you prove that the exchange has funds to pay back all depositors.

The easiest way to prove a deposit is to simply publish a list of (username, balance) pairs. Every user can check if their balance is included in the list, anyone can check the complete list, see:

Each balance is non-negative;

The total is the claimed amount.

Of course, this breaks privacy, so we can change the scheme a bit:

Publish a list of (hash "username, salt", balance) pairs, and privately send each user their salt value. But even that would give away balances and patterns of balance changes.

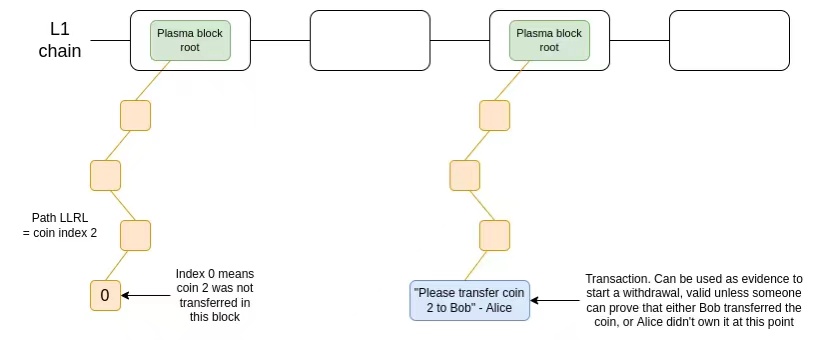

Merkle tree technique.

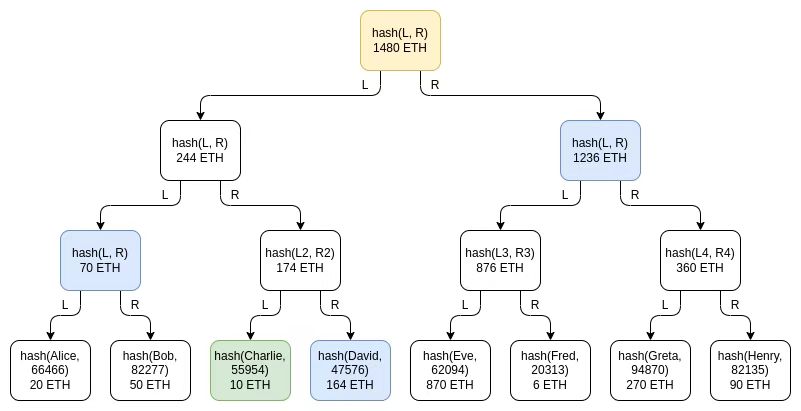

image description

Green: Node representing Charlie. Blue: Denotes generation nodes that Charlie will receive as part of the proof. Yellow: Represents the root node, which is publicly displayed to everyone.

The exchange will send each user a Merkel proof of deposit. Users will then be given a guarantee that their balance is correctly included as part of the total. allowableherehere

Find a simple sample code implementation.

The privacy leaked in this design is much lower than a fully public list, and can be further reduced by moving the branch every time the "root" is released, but there is still some privacy leak: Charlie learns that someone has a balance of 164 ETH , there are two users whose balances add up to 70 ETH and so on. An attacker who controls multiple accounts could still learn a great deal about an exchange's users.

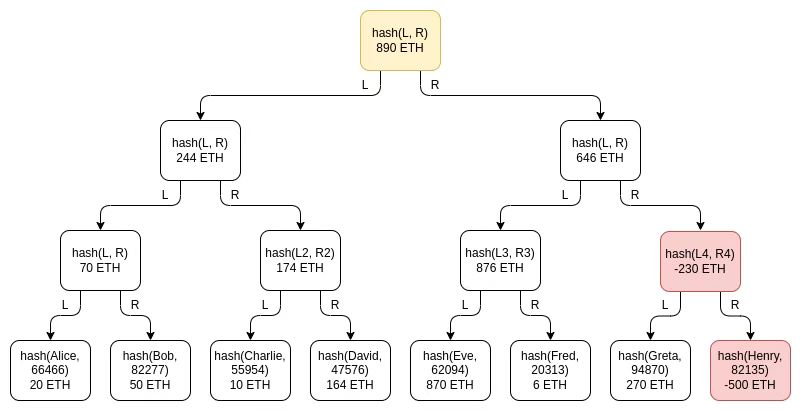

An important subtlety of the scheme is the possibility of negative balances: if an exchange has a customer balance of 1390 ETH, but only has 890 ETH in reserve, try adding -500 ETH under a fake account somewhere in the tree Balance to make up the difference, what should I do? It turns out that this possibility doesn't break the scheme, which is why we specifically need Merkle sum trees instead of regular Merkle trees. Assuming Henry is a fake account controlled by the exchange, where the exchange put -500 ETH:

If the exchange can identify 500 ETH worth of users that they trust will either not bother to check the proof, or trust them when they complain that they never received the proof, they can escape suspicion of misappropriation. However, exchanges can also exclude these users from the tree and have the same effect. Therefore, Merkle tree technology is basically as good as a proof of responsibility scheme if the goal is only to achieve proof of liability. But its privacy properties are still not ideal. You can use Merkle trees in smarter ways, like making each satoshi or wei a separate leaf, but ultimately with more modern techniques, there are better ways to do this.

secondary title

Improving Privacy and Robustness Using ZK-SNARKs

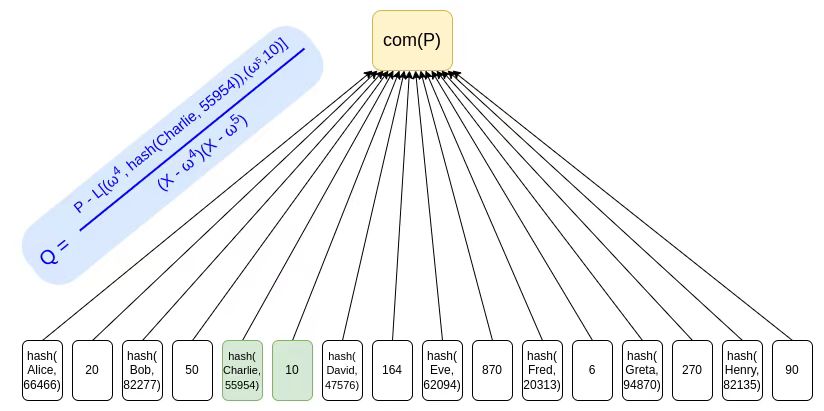

The simplest thing we can do is put all users' deposits into a Merkle tree (or, simpler, a KZG commitment), and use a ZK-SNARK to prove that all balances in the tree are non-negative, and add Appears to be some claimed value. If we add a layer of hashing for privacy, the Merkle branch (or KZG proof) given to each user will not reveal any other user's balance.

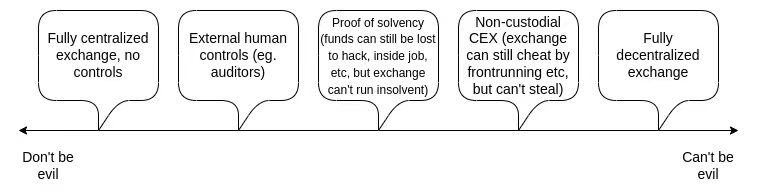

image description

Using KZG commitments is a way to avoid privacy leaks, because there is no need to provide "sister nodes" as proof, and a simple ZK-SNARK can be used to prove the sum of balances, and each balance is non-negative.

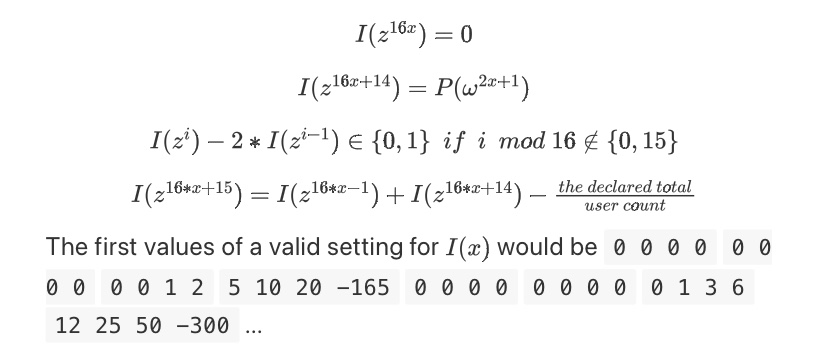

We can use a dedicated ZK-SNARK to prove the summation and non-negativity of the balances in the above KZG. Here is a simple example. We introduce an auxiliary polynomial I(x) that makes up a fraction of each balance (we assume balances below 215), tracking a sum with an offset every 16 positions, only if the actual sum is the same as the declared sum It only sums to zero when there is a match. If z is the -128th root of unity, we can prove the following equation:

In the longer-term future, such ZK proofs of debt may be used not only for customer deposits on exchanges, but also for loans more generally. Anyone taking out a loan puts the record into a polynomial or tree containing the loan, and the root of that structure is published on-chain. This will allow anyone seeking a loan to demonstrate to lenders that they have not taken out too many other loans. Ultimately, legal innovations may even give loans committed in this way a higher priority than loans that are not. this is with us in"Decentralized Society: Finding the Soul of Web3"secondary title

Proof of assets

The simplest version of Proof of Assets is the protocol we saw above: to prove that you hold X tokens, you simply move X tokens at a pre-agreed time, or include in the data field "These funds belong to Binance" Move X tokens in a transaction of . To avoid paying transaction fees, you can sign an off-chain message. Both Bitcoin and Ethereum have standards for signing messages off-chain.

There are two practical problems with this simple proof-of-asset technique:

There are two practical problems with this simple proof-of-asset technique:

Cold wallet handling;

For security reasons, most exchanges keep the vast majority of customer funds in cold wallets. On offline computers, transactions need to be manually signed and transferred to the Internet. The cold wallet setup I used to store personal funds in the past required a permanently offline computer to generate a QR code containing a signed transaction, which I then scanned with my phone. Current exchange protocols are crazier, often involving multi-party computations between multiple devices. In this setup, crafting an additional message to prove control of an address is an expensive operation.

Exchanges can use the following methods:

Exchanges can use the following methods:

Reserve some public long-term use addresses. The exchange will generate a few addresses, issue a proof of each address once to prove ownership, and then reuse those addresses. This is by far the easiest option, though it does add some limitations in how you can protect your security and privacy.

There are many addresses, just prove a few. The exchange will have many addresses and maybe even use each address only once and exit after a single transaction. In this case, the exchange might have a protocol where some addresses are chosen randomly from time to time and must be "opened" to prove ownership. Some exchanges already run similar operations with auditors, but in principle, this technique could be turned into a fully automated procedure.

More complex ZKP options. For example, an exchange could set all its addresses to 1/2 multisig, where each address has a different private key, and the other is a blinded version of some "important" emergency backup key, in some way Complex but secure storage, such as 12/16 multi-signature. To preserve privacy and avoid revealing their full addresses, an exchange can even run a zero-knowledge proof on the blockchain proving the total balance of all addresses on the chain with this format.

Another major concern is preventing dual use of collateral. Transferring collateral back and forth between each other to prove reserves, which is easy for exchanges to do, will allow them to pretend to be solvent when they really are not. Ideally, proofs of solvency should be done in real time, with an updated proof after each block. If this is impractical, the next best thing is to coordinate across exchanges on a fixed schedule, such as proving reserves every Tuesday at 2pm UTC.

Another approach is to completely separate one entity that operates an exchange that handles asset-backed stablecoins (such as USDC) from another entity that handles the process of moving cash in and out between cryptocurrencies and the traditional banking system (USDC itself). Because the "liability" of USDC is only the ERC20 token on the chain, the proof of liability is "free", and only asset proof is required.

secondary title

Plasma and validiums scaling solutions: can we achieve non-custodial CEX?

Suppose we want to go a step further: we don't want to just prove that the exchange has the funds to pay back the user. Instead, we want to prevent outright exchanges from stealing users' funds.

The first major attempt was Plasma, a scaling solution that became popular in Ethereum research circles in 2017 and 2018. Plasma works by splitting the balance into a set of independent "tokens", where each token is assigned an index and resides at a specific position in the Merkle tree of a Plasma block. To have a valid token transfer, a transaction needs to be placed in the correct place of the tree where the root is published on-chain.

An oversimplified diagram of a version of Plasma. Tokens are kept in a smart contract that enforces the rules of the Plasma protocol when withdrawing.

Since the upsurge of the Plasma discussion in 2018, ZK-SNARKs have become more suitable for use cases related to scaling. As we said above, ZK-SNARKs have changed everything.

A more modern idea of Plasma is what Starkware calls validium: basically the same as ZK-rollup, except the data is kept off-chain. This structure can be used in many use cases, imagine any situation where a centralized server needs to run some code and prove that it is executing the code correctly. During the validity period, there is no way for the operator to steal funds, although depending on implementation details, some amount of user funds may be stuck if the operator disappears.

CEXs and DEXs are not binary, it turns out they have a range of options, including various forms of hybrid centralization, where you get some advantages like efficiency, but there are still a lot of cryptographic barriers against centralized operators abuse.

Handling user errors is also a big problem. By far the most important type of error is – what if a user forgets their password, loses their device, gets hacked, or loses access to their account?

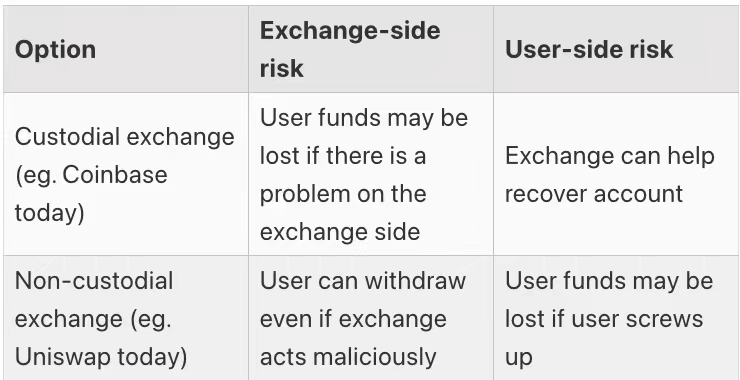

The ideal long-term solution is to rely on self-custody, with the help of technologies such as multisig and social recovery wallets to help users deal with emergencies. But in the short term, there are two obvious alternatives with significantly different costs and benefits:

secondary title

Summary: Looking to the Future for More Advanced Exchanges

In the short term, there are two clear categories of exchanges: custodial exchanges and non-custodial exchanges. Today, the latter category is just a DEX like Uniswap, and in the future we may also see CEXs with limited encryption technology, where user funds are held in a form similar to validium smart contracts. We may also see semi-custodial exchanges where we trust them to work with fiat currencies, not cryptocurrencies.

Both types of exchanges are here to stay, and the easiest backwards-compatible way to improve the security of custodial exchanges is to add proofs of reserve. This includes a combination of proof of assets and proof of liabilities. There are technical challenges to crafting good protocols for both, but we can and should make progress on both as much as possible, and open source software and processes as much as possible so that all exchanges can benefit.