DeSci: A new financial model for the repurposing of generic longevity drugs

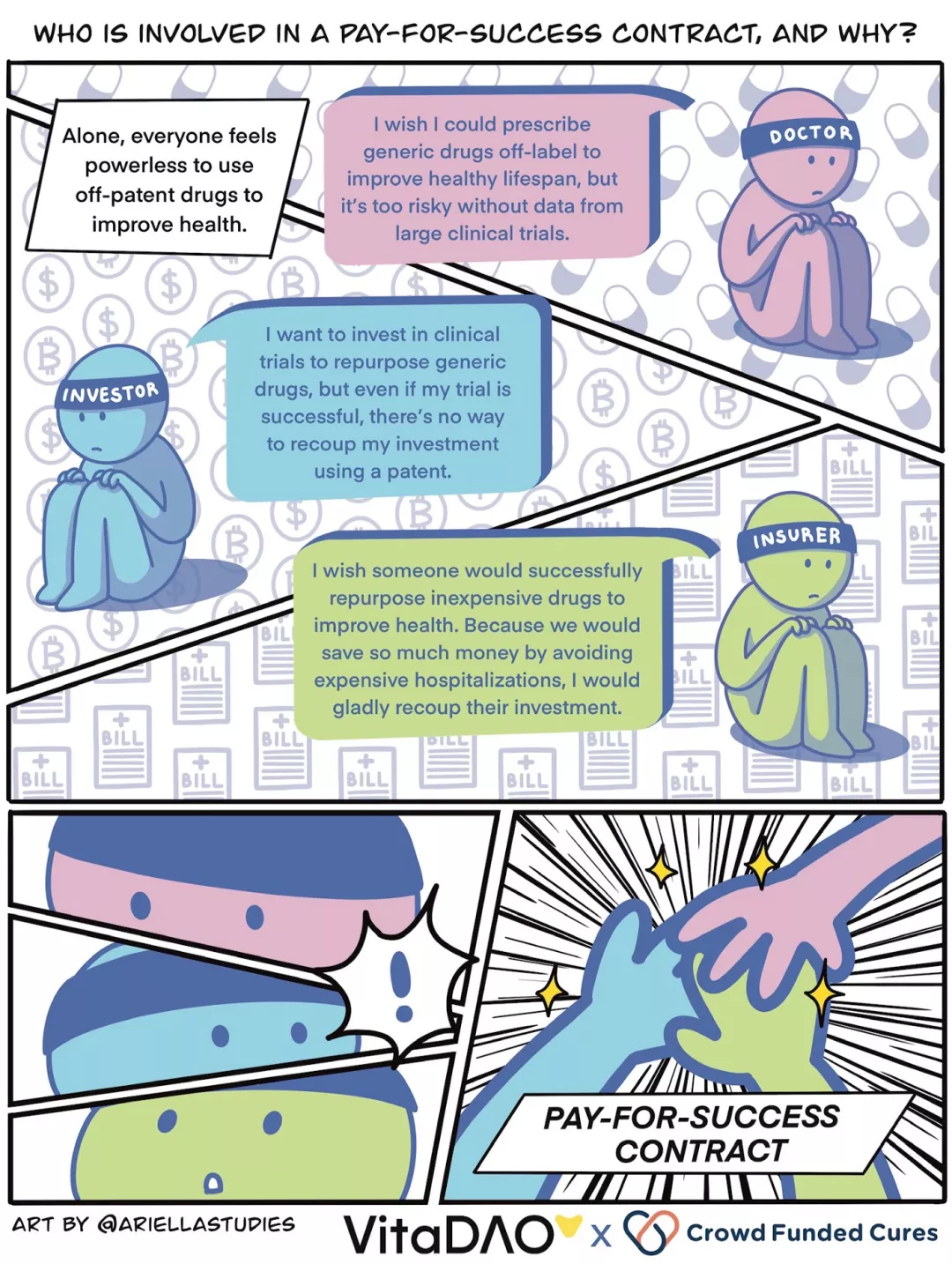

Under the current system, patent protection is crucial to the development of new treatments. The large clinical trials required to gain regulatory approval can cost tens of millions of dollars, and royalties are a way to recoup that investment and earn a return. So if a drug is a generic or generic, it has little chance of being repurposed to treat a new disease, even if it is safer and more effective than the new patented drug. This is because, because pharmaceutical companies are not the only manufacturers, they cannot monopolize the price of generic drugs. Physicians can prescribe drugs for unapproved indications based on their knowledge of small, low-quality research programs; however, they are often reluctant to do so for fear of putting patients at risk.

In this article, we contrast the old approach to drug development (based on patenting new molecules and charging monopoly prices) with the new "pay-for-success" model of financial innovation. Under this new system, health insurers pay subsidized prices for generic drugs and promise overall cost savings through improved health outcomes and fewer hospitalizations. This incentivizes investors to repurpose generic drugs to treat new diseases, potentially 100 times cheaper and 10 times faster than new drugs developed under the old patent model. The reason it's so cheap and fast is because years, if not decades, of generic drug safety data keep clinical trials well ahead. Here, we compare the two models side by side using generic rapamycin treatment of aging as a hypothetical example.

Reuse of Generic Drugs under Current Patent Mode

A researcher has found in a small study that a certain generic drug, rapamycin, is particularly effective at improving biomarkers of aging at certain doses and in patients with certain genetic profiles and age groups. Unfortunately, because rapamycin is a generic drug, researchers struggled to secure the large clinical trial funding required for regulatory approval. Concentrated grant and philanthropic funding is competitive with other, more prestigious research institutions. Funders don't want to take the political and financial risk of failing a large clinical trial. For this reason, clinical trials of generic rapamycin are unlikely to be funded and can only be prescribed off-label by physicians, who are reluctant to do so based on small clinical trials. It is also difficult to obtain philanthropic funding due to the high risks and costs of large clinical trials.

Researchers come to their university's technology transfer office to see if they can get noticed by industry. Industry's only chance is to work with patent attorneys and try to patent "rapamycin," a new off-patent modified version of "rapamycin." The engineered rapamycin molecule also has fewer safety data than the off-patent rapamycin, making it a potential risk to patients. A pharmaceutical company decides to fund a modified version of rapamycin that could be patented and raise hundreds of millions of dollars. It won regulatory approval and billed health insurers billions of dollars in monopoly fees. To make matters worse, doctors stopped prescribing rapamycin after a few years when they discovered that the patented rapamycin was as effective, if not less effective, than generic rapamycin. For this reason, industry has been reluctant to fund further studies of rapamycin to determine optimal treatment regimens and dosages. In the end, all games were lost.

Reuse of Generic Drugs under the Pay-for-Success Model

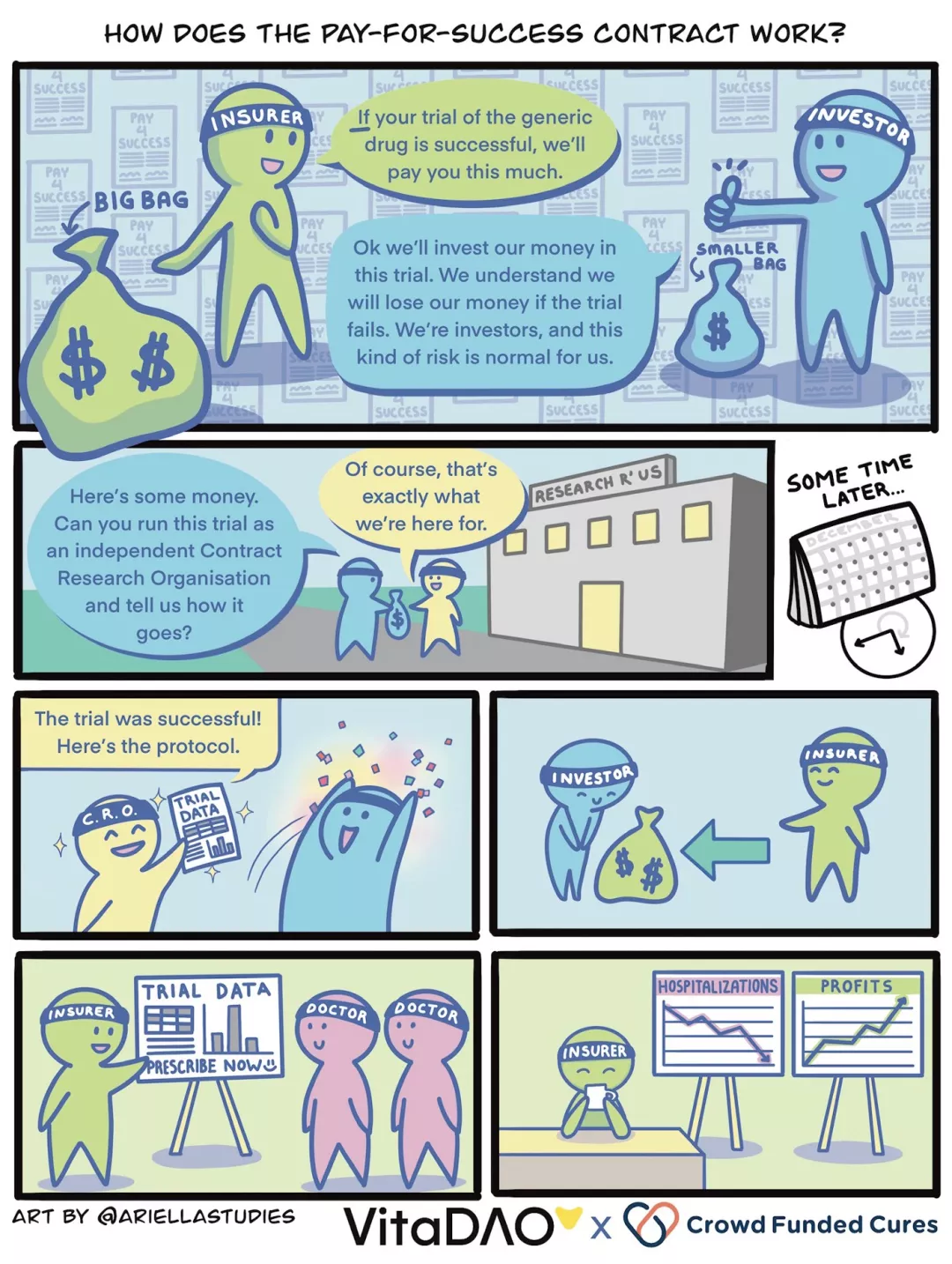

A researcher in a small research project has found that a certain generic drug, rapamycin, is particularly effective at improving biomarkers of aging at certain doses and in patients with certain genetic profiles and age groups. Under the pay-for-success model, researchers do not need to rely on patent protection to raise funds for clinical trials. That's because health insurers have agreed to pay up to $30 million in subsidized prices for successfully repurposed generics, and the drug will result in cost savings of more than $100 million due to an overall reduction in hospitalizations. This conclusion was supported by the pharmacoeconomic analysis of the feasibility study (lower cost of quality-adjusted life years).

In this hypothetical example, let us envision a scenario where the VitaDAO community acts as an investor. To improve efficiency, gain liquidity, and leverage token economics and market power, the pay-to-success model is enabled in a trustless manner through smart contracts and Molecule's IP-NFT framework. It allows token holders to take ownership of generic drug reuse clinical trial data, such as VitaDAO members collectively funding $10 million for an "open source rapamycin" IP-NFT.

Regardless of who takes the role of investor and provides the funding, let's imagine we now have $10 million to spend. The $10 million is used to pay an independent trusted research organization (CRO) to conduct a clinical trial that, if successful, would lead to regulatory approval and labeling for a "new brand" generic version of rapamycin, the health insurer Agreed to pre-order $20 million of the rapamycin brand at a subsidized price, with an additional $10 million to be purchased if clinical efficacy is assured. Proceeds will be distributed to investors, IP-NFT owners, according to arrangements with generic drug manufacturers.

in conclusion

in conclusion

Using the pay-for-success contract model avoids an unreasonable and complete reliance on the patent system to fund biopharmaceutical R&D and clinical trials. Information about which generic or generic medicines are safe and effective in treating new diseases or improving healthspan, and their optimal dosing regimens will typically be of public interest. By establishing this new pay-for-success model, we can ensure that researchers follow the science, rather than mandate patentable methods. Researchers will be able to secure funding for large-scale clinical trials and, without relying on patents, identify generic treatments that could help patients.