多角度解读Rollup去中心化的重要性

原文作者:Shivanshu Madan

原文编译:Luffy,Foresight News

最近 Crypto Twitter 上的很多讨论都围绕 L2 的去中心化。我们正在构建的 Rollup 是否足够去中心化?它们已经走上了权力下放的道路吗?这还重要吗?

我将在这篇文章中探讨这些主题。在我深入研究之前,如果你还不了解 Rollup 的真正工作原理,建议你快速阅读一下这篇文章:Rollups for Dummies。

Rollup 的理念其实很简单:它希望链下参与者进行交易,然后可以轻松地在链上验证。通过 Rollup,基础层的「信任」被扩展到其区块链之外的活动。作为回报,Rollup 支付少量费用(租金)来使用这种信任。

那么我们是否需要去中心化 Rollup?

直观的答案是:肯定需要!这是区块链的精神所在。

但是,我也相信这个问题的答案并不是简单的是或否。相反,它包含多个方面,必须逐个单独分析。在接下来的内容中,我将从哲学、技术和经济三个角度来探讨这个问题。

哲学角度

让我们首先将对话提升一个层次:为什么我们关心权力下放?

因为我们想要一个促进开放创新的无需许可的未来。我们希望用户能够不受任何限制地构建新事物,并且不需要信任任何单个实体。

在区块链短暂的历史中,我们已经有很多匿名开发者构建了令人惊叹的东西。事实上,比特币本身是由一个匿名实体创建的,它可能很快就会成为世界上大多数人使用的全球支付货币。这就是无需许可的创新的力量!

区块链让我们能够与没有任何共同点的人合作,而且我们知道他们没有办法打破这种信任关系。

——Preston Evans

比特币和以太坊等去信任网络的去中心化基础使我们能够构建这样的未来。很明显,任何与这些区块链有信任关系的链,比如 Rollup,也应该是去中心化的!

事实上,它引出了一个有趣且重要的问题:

如果 Rollup 不是去中心化的,这是否意味着以太坊就不是去中心化的?

看待这个问题的一种稍微乐观的方式是,在一个无需许可的世界中,应该允许 Rollup 构建它们想要的任何东西,包括(但不限于)许可链,并且该 Rollup 的用户仍然能够利用基础层的安全性。只要基础层是去中心化的,并且 Rollup 已经「完整实现」(我们将在技术部分更多地讨论「完整实现」),即使是许可链也应该可以安全使用。

但实际情况是,今天的大多数 Rollup 尚未达到完整实现的阶段,而且它们没有为用户提供所需的安全性和免信任级别。

那么,Rollup 的正确实现方式是什么样的呢?让我们来看看:

技术角度

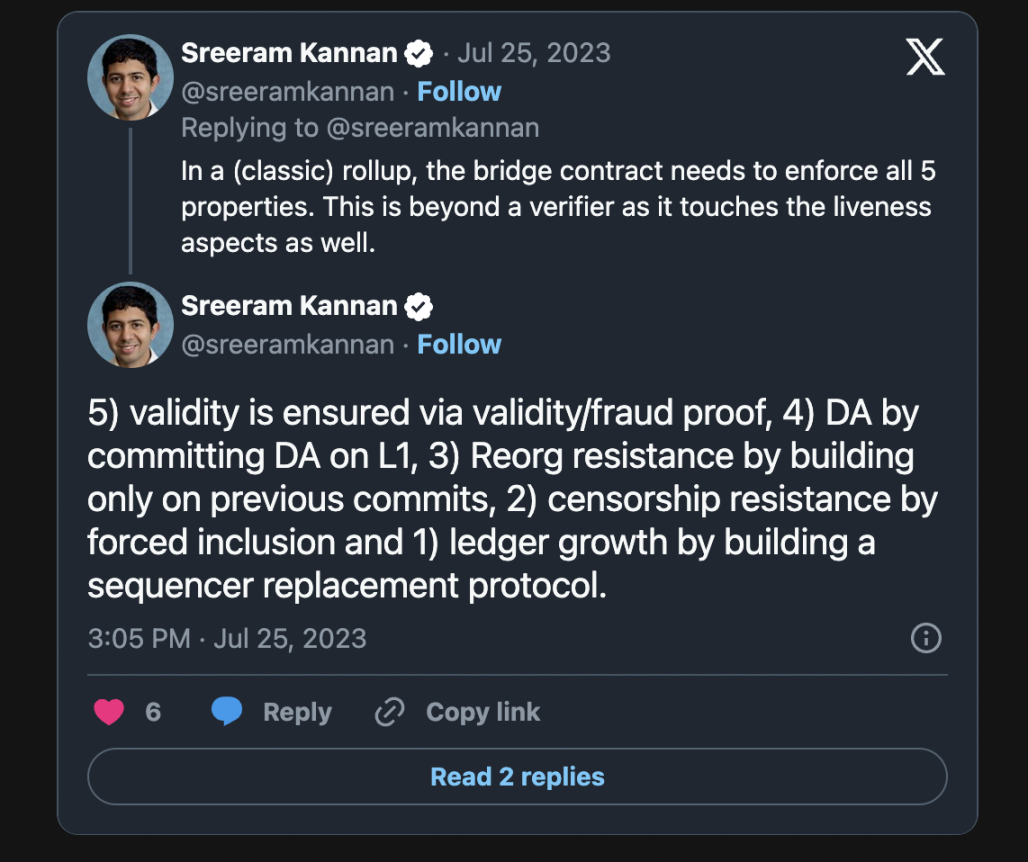

要真正理解 Rollup 的去中心化和安全性问题,我们需要从第一性原理来看待它。没有多少人能比 Sreeram Kannan 更好地解释区块链的首要原理。

区块链是一种分布式账本,网络中的不同节点遵循预定的协议规则以获得对账本状态的共识。根据这些节点如何看待网络,它们可以有不同的规则,用于确认自己的账本网络的正确状态。

特别是在 Rollup 中,全节点与轻客户端具有不同的确认规则。在传统的智能合约 Rollup(SCR)中,智能合约(验证桥)有自己的确认规则。如果没有不良事件,这些确认规则最终会在所谓的「一致性区域」中重合。顾名思义,在一致性区域中,所有参与者对网络都有相同的看法(以及账本中相同的历史记录)。

如果所有确认规则都是安全的,就不会发生不良事件。正如 Sreeram 在上面的帖子中分享的那样, 5 个属性主要定义了这些确认规则的安全性。

账本增长 - Rollup 链应该不断增长(活性)

抗审查性 - 所有用户都应该能够将任何交易包含到基础层

抗重组 - 交易一旦完成就不会被撤回

数据可用性 - 交易数据应该在某处发布

有效性 - 交易和状态转换应该有效

前 2 个属性定义了系统的「活性」条件,而后 3 个属性定义了「安全」条件。

让我们从不同 Rollup 参与者的角度来审视这些问题,看看在不去中心化的情况下,哪些问题可以缓解。

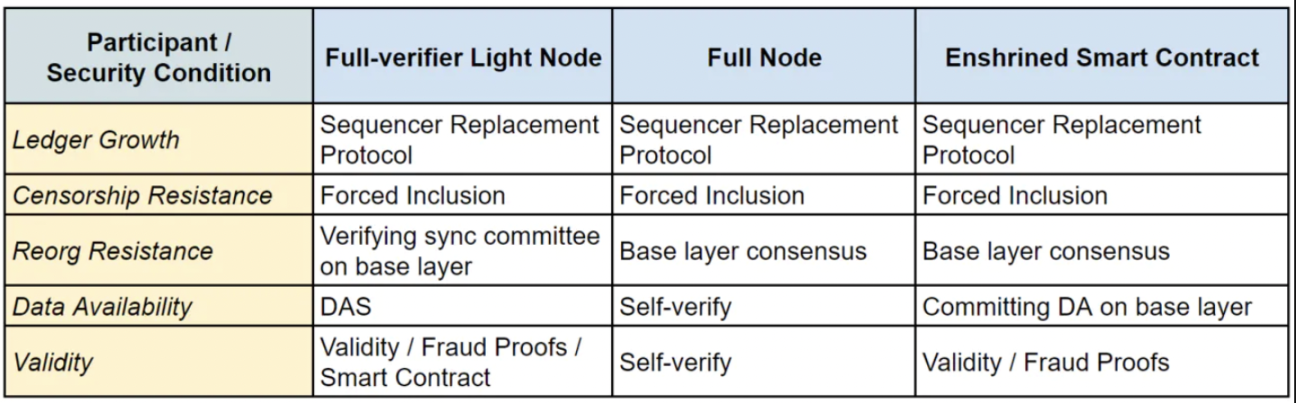

不同的参与者依靠不同的机制来获得安全性和活性

全节点:

如果运行全节点,则可以访问已发布的数据并可以直接对其进行验证。然后,你可以使用该数据自行执行交易,并确定交易的有效性以及这些交易后 Rollup 的最终状态。

因此剩下的安全条件是活性和抗重组性。对于抗重组性,全节点依赖于基础链的验证器及其使用的共识协议,而对于活性,全节点依赖于排序器和 Rollup 实现。

轻客户端:

大多数用户使用轻客户端获取区块链数据来与区块链交互。轻节点有多种类型:

状态验证者 - 验证状态转换的有效性

数据可用性验证者 - 验证数据可用性

共识验证者 - 验证基础层的共识证明

完整验证者 - 验证以上所有内容

如果运行完整验证者轻客户端,可以通过数据可用性采样来验证数据是否可用,可以通过有效性证明或欺诈证明来验证状态转换的有效性,还可以验证状态是否遵循基础层的共识(在以太坊上,可以通过遵循同步委员会来完成)。

那么剩下的安全条件就是活性,轻客户端依赖于排序器和 Rollup 实现。

内置智能合约(验证桥):

在传统 SCR 中,智能合约的「确认规则」是强制执行所有 5 个安全属性:

通过排序器替换协议实现账本增长

通过强制包容来抵制审查

在先前状态的基础上构建抗重组

通在基础层提交 DA 实现数据可用性

通过有效性 / 欺诈证明来验证有效性

SCR 全节点依靠智能合约来强制执行活性属性。它们从基础层获得抗重组性。

轻节点依靠智能合约来增强活性属性并吸收来自基础层的 DA 和抗重组性。它们可以自己或通过智能合约验证有效性证明。

SCR 的共识是遵循智能合约定义的规范链。

主权 Rollup 怎么样?

主权 Rollup 没有智能合约(验证桥)来强制执行有效性或活性条件。相反,它们将证明「下滚」(roll down)到下游的 Rollup 节点。这些节点仍然依靠来自基础层的数据可用性和抗重组性。

就像在 SCR 中一样,在主权 Rollup 中,节点需要某种机制来强制执行活性属性。为了定义规范链,它们选择了独立的机制,例如广播 p2p 证明。

这一切与去中心化有什么关系?

无论是智能合约 Rollup 还是主权 Rollup,活性属性都来自 Rollup 的正确实现。正如我们在上面所看到的,Rollup 的正确实现必须包括两个重要的组成部分:

强制包含机制;

排序器替换协议。

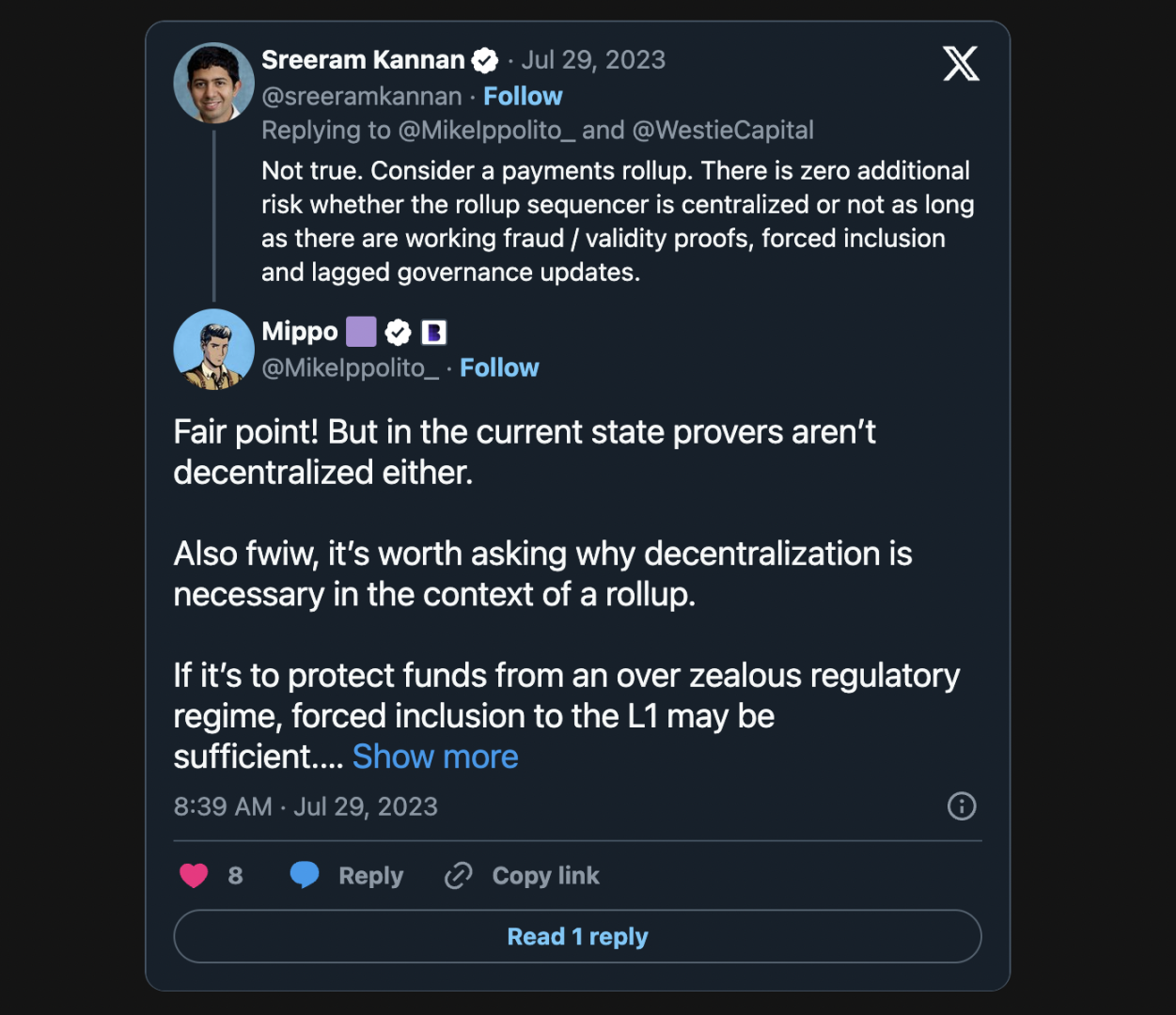

强制包含机制有助于增强抗审查性。这种机制允许用户将他们的交易直接「强制包含」在基础层中。然后,Rollup 上的任何用户都可以将他们的资金强制退出回到基础层。因此,即使只有一个中心化的排序器节点,只要有成熟的强制包含机制,它就无法审查用户。

但这就足够了吗?

即使用户可以自由退出,这可能意味着如果大多数用户都跑回 L1,L2 就没有太多动力继续运营。此外,强制包含机制通常需要很长的等待时间,并且对于普通用户来说执行起来可能相当昂贵。这种机制提供的抗审查性并不完全实用(或实时),我们可以称之为「弱审查」。

那么我们就有了最终的活性属性——账本增长。

如果中心化排序作恶,它可以通过简单地停止区块生产来阻止 Rollup 链的增长。如果发生这种情况,用户无法采取任何措施使 Rollup 再次「生效」。

为了解决这个问题,我们需要一个排序器替换协议。

排序器替换协议的想法是,如果排序器以恶意方式运行,则 Rollup 能够通过治理启动一个新的排序器。实现这一目标的方法之一是用去中心化排序器协议替换中心化排序器节点。如果排序器是去中心化的并且不垄断 Rollup 的区块构建,那么它就几乎不可能阻止 Rollup 链。

因此,尽管用户资金在通过强制包含机制实现的 Rollup 中始终是安全的,但建立强大的排序器替换协议有助于保持 Rollup 的活性并提供实用、实时的抗审查性。

这就是全部?

不完全是。从技术角度来看,还有一个方面需要考虑:

如果智能合约本身可以由 Rollup 的中央委员会升级怎么办?假设 Rollup 目前已正确实施,但明天委员会达成共识,我们不再需要智能合约,而是将 Rollup 状态的证明广播到 p2p 网络。

如果作为 Rollup 用户,你不同意此类升级,则你应该能够在实施升级之前退出 Rollup(尽管这不是一个好的用户体验,并且可能对企业不利)。这可以通过「滞后的治理更新」来实现,就像一个「通知期」,之后将实施升级。不同意更新的用户可以在通知期内退出。

去中心化的极端是拥有完全不可变的智能合约。这些合约不由任何多重签名钱包或其他委员会管理,并且一旦部署就永远无法升级。

当然,这也有其自身的问题。如果代码中存在任何错误,或者某些重大事件需要更新智能合约,那么 Rollup 唯一的选择就是分叉到新的智能合约,而用户资金滞留在旧合约中。

不幸的是,Rollup 的当前状态远未达到我们上面讨论的完整实现。大多数 Rollup 仍处于「探索」阶段,正在努力正确实施。

根据 L2 BEAT 的说法,Fuel v1 和 DeGate 是仅有的两个已经成熟、可以实现所有活性和安全条件的 Rollup。

经济角度

最后,让我们从用户和 Rollup 运营商的角度来看看 Rollup 经济学:

用户体验:用户应该获得便宜的价格,并且交易不必等待太长时间;

Rollup 利润:排序器和代币持有者应该有利可图。

当用户获得快速且廉价的交易服务时,用户体验就会得到优化。

交易最终确定的速度取决于基础层最终确定的速度。每当 L1 上的数据最终确定时,交易就可以被视为最终交易。然而,运行全节点的用户也可以通过简单地执行交易并确定最终状态来获得即时最终结果。

但对于每个人来说都运行全节点并不实际。因此,中心化排序器很有用,因为它可以向用户提供「软确认」,表明他们的交易已包含在区块中并将最终完成。这对于大多数用例来说已经足够了。然而,它依赖于可以采取不利行动的中心化机构。

虽然一些排序器替代协议解决方案放弃了此属性(因为对用户不利),但其他解决方案(例如外部 PoS 共识方案 Espresso)可以提供类似的预确认保证,而无需承担中心化排序器的风险。

用户成本又如何呢?

Rollup 交易的显式成本通常为:

L2 Gas 成本 = L1 Gas 成本 + 排序器费用。理性的中心化排序器总是希望最大化自己的利润,即使这意味着将更高的成本转嫁给用户。然而,值得注意的是,这也不一定可以通过去中心化排序器机制来解决。即使是去中心化排序器中的 PoS 节点也希望最大化自己的利润。

事实上,这会产生错配问题,即 Rollup 可能不想将利润交给外部排序器。

Rollup 利润:除了排序器费用外,Rollup 还可以通过从用户交易中提取 MEV 来赚取利润。此 MEV 通常很难归因,因为很难找到排序器是否在交易包中包含一些自己的抢先交易。

如果 Rollup 被外部 PoS 共识取代,他们就会将此 MEV 交给外部运营商。

值得注意的是,Rollup 将收入交给外部机制的这两个问题都可以通过 Rollup 和外部机制之间的「交易协议」来解决。

然而,正如 Jon Charbonneau 在模块化峰会期间的演讲以及随后的文章中所解释的那样,更好的想法可能是让 Rollup 治理将排序委托给一组经过验证的节点。这些节点可以战略性地选择在地理上分散,并且治理可以简单地将不良行为者踢出。

这可能是一种一石二鸟的解决方案,因为它允许 Rollup 将利润保留在内部,同时还减轻了中心化排序器的不利影响。

但与此相反的是,在排序器轮换有限的情况下,排序器可以具有短视行为,这可能导致垄断定价 / 价格欺诈,进损害牲 Rollup 用户的利益。

无论哪种方式,为了使 Rollup 对用户来说经济高效,一些排序器替换协议是必要的。

结论

无论 Rollup 采取什么路径,至关重要的是,它的目标应该是一个完整的实现,具有成熟的排序器替换协议、强制包含和滞后治理更新机制。如果有强制包含和滞后更新机制,无论排序器是否集中心化,用户资金都会是安全的。

然而,强大的排序器替换协议可以提高活性保证,并可能提高 Rollup 用户的经济效益。