a16z:需要监管的应是Web3应用,而非协议

原文作者:Miles Jennings

原文编译:DeFi 之道

互联网的许多早期支持者主张永远保持自由和开放,使其成为全人类的无边界和无监管的工具。在过去的 20 年里,随着政府对滥用行为的打击,这一愿景失去了一些明确性。然而,尽管如此,互联网的大部分基础技术 -- 通信协议,如 HTTP(网站的数据交换)、SMTP(电子邮件)和 FTP(文件传输)-- 仍像以往一样自由和开放。

世界各国政府通过接受该技术依赖于开源、去中心化、自主和标准化的协议来维护互联网的承诺。当美国通过 1992 年的《科学和先进技术法案》(Scientific and Advanced Technology Act)时,它为商业互联网的繁荣铺平了道路,且没有篡改 TCP/IP 这一计算机网络协议。当国会通过 1996 年《电信法》(Telecommunications Act)时,它没有干涉数据穿越网络的方式,但仍然提供了足够的清晰度,使美国能够与现在的巨头如 Alphabet、亚马逊、苹果、Facebook 和其他公司一起主导互联网经济。虽然没有立法是完美的,但这些护栏允许行业和创新的发展,使我们今天能够享受许多互联网服务。

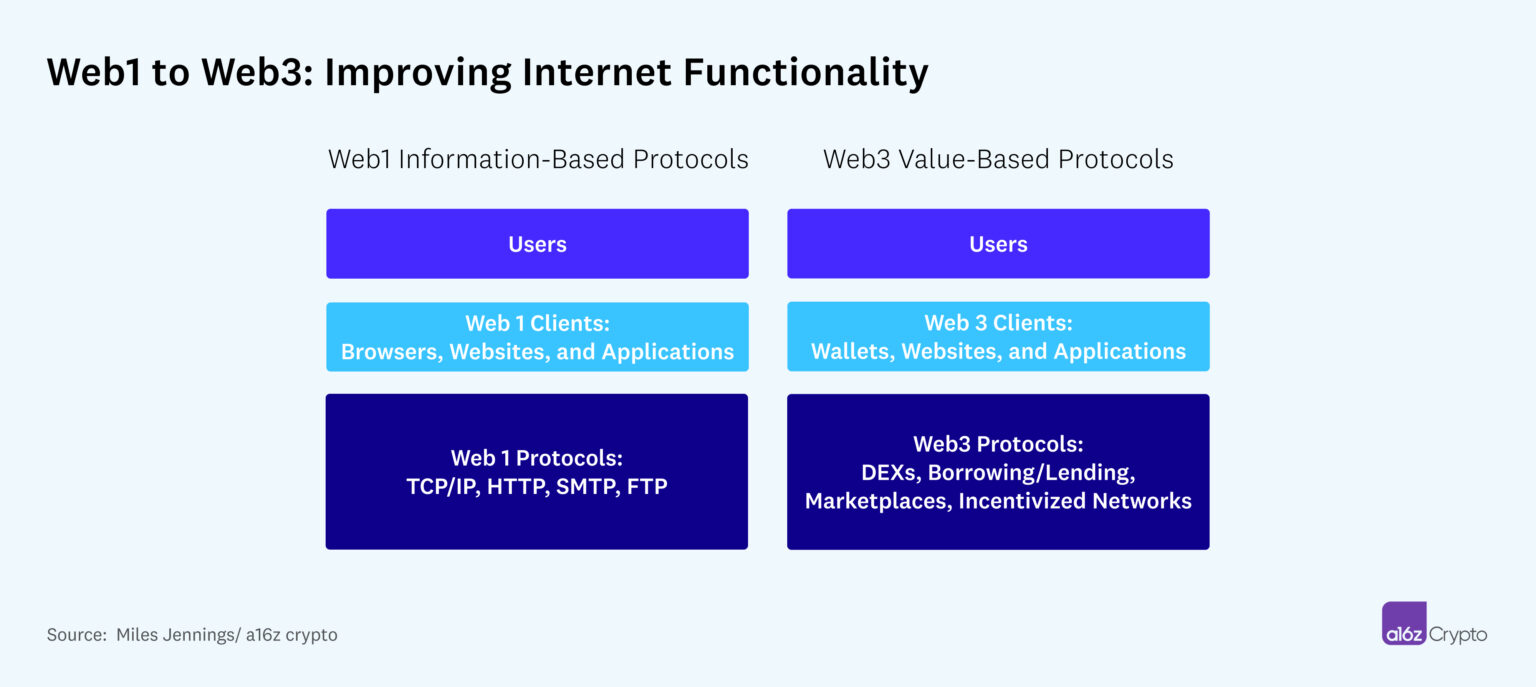

主要的有利因素之一是:政府没有监管协议,而是寻求监管应用程序,包括浏览器、网站和其他面向用户的软件等应用,通常被称为 "客户端"-- 用户通过它们访问网络。这条仍然管理网络的准则应该延伸到 Web3,这是互联网的进化,它将具有新的应用程序或客户端,如 webapps 和钱包,以及先进的去中心化协议,包括由区块链和智能合约实现的价值交换结算层。问题不在于是否应该有 Web3 监管。这个问题的答案是显而易见的。规则是必要的,也是受欢迎的。问题是,在技术堆栈的哪一层,Web3 监管是最有意义的。

今天,典型的网络用户体验可能包括通过受监管的互联网服务提供商进行连接,然后通过受监管的浏览器、网站和应用程序访问信息,其中许多都依赖于自由和开放的协议。政府可以通过对网站内容实施访问限制,或要求遵守隐私规则和版权摘录请求,来塑造这种网络体验。这就是美国如何迫使 YouTube 撤下恐怖分子的招募视频,而不对 Dash(一种视频流媒体协议)采取措施的方式。

有几个原因可以说明协议层面的监管是不可取的,而且是不可行的。首先,协议在技术上不可能符合法规,因为法规往往需要无法定义的主观判断。其次,协议要纳入全球法规是不切实际的,这些法规因司法管辖区的不同而不同,并可能发生冲突。第三,鉴于应用程序或客户端可以遵守更高层次的技术规范,重写网络的技术基础是不必要的,而且会产生反作用。

以下,让我们更详细地阐述下每个原因。

协议在技术上不能符合主观规定

无论一项法规的用意有多好,如果它需要主观评估,那么它对协议的应用将是灾难性的。

比如垃圾邮件。对垃圾邮件的憎恨几乎是普遍的,但如果当局规定电子邮件协议(SMTP)为发送垃圾邮件提供便利是非法的,那么今天的网络会是什么样子?垃圾邮件的定义在本质上是主观的,并随着时间的推移而变化。像谷歌这样的大公司花费巨资试图从他们的电子邮件应用或客户端(如 Gmail)中消除垃圾邮件 -- 但他们仍然会犯错。此外,即使某些机构强制要求 SMTP 默认过滤垃圾邮件,但由于协议是开放源码的,恶意行为者仍然可以简单地对过滤器进行反向工程,以规避它。因此,禁止 SMTP 为垃圾邮件的发送提供便利,要么是无效的,要么就是我们所知的电子邮件的终结。

在 Web3 中,我们可以在去中心化交易协议(DEX)的背景下将代币与电子邮件进行类比。如果政府希望禁止使用这种协议交换他们认为可能是证券或衍生品的某些代币,他们需要能够阐明客观上符合这种分类的技术规范。但这种客观的分类标准是不可能的。确定一项资产是否是证券或衍生品是主观的,需要对事实和法律进行分析。即使是美国证券交易委员会也在努力解决这个问题。

试图将二阶主观分析嵌入基础层指令集是一种徒劳的做法。就像 SMTP 一样,像 DEX 这样的去中心化和自治的协议没有办法在不增加人类中介的情况下进行主观分析,从而否定协议的去中心化和自治性。因此,对 DEX 应用这种规定将有效地禁止这种协议,从而将一个新兴的科技创新类别完全取缔,并危及所有 Web3 的生存能力。

协议不能实际遵守全球法规

即使在技术上有可能建立能够做出复杂和主观决定的协议,在全球范围内这样做也是不现实的。

想象一下冲突的泥潭。SMTP 使我们能够向世界上的任何人发送电子邮件,但如果美国要求 SMTP 过滤垃圾邮件,我们可以假设外国政府也会要求类似的限制。此外,由于垃圾邮件的定义是主观的,我们也可以假设政府的要求会有所不同。因此,即使在技术上有可能建立能够做出复杂和主观决定的协议,这样做也与建立一个在全球范围内实用的标准的概念背道而驰。SMTP 根本不可能纳入 195 个国家不断变化的垃圾邮件过滤器要求,即使协议可以,它也不知道用户在哪个国家,以及如何公平地确定竞争的优先次序。在协议中加入主观性,破坏了使协议有用的支柱之一:标准化。

规则是取决于环境。在 Web3 中,证券和衍生品法律允许的内容因国家而异,而且这些法律一直在变化。DEX 没有办法为这些法律建立一个全球标准,而且,像 SMTP 一样,没有办法根据地域来限制访问。最终,如果协议被要求建立在不断变化的全球监管之上,那么它们就没有办法取得成功。

通过让应用程序或客户端遵守规定来避免这些问题

现在,为什么监管应用程序而不是协议是至关重要的,应该很明显了。应用程序层面的监管可以实现政府的目标,而不会危及底层技术。我们知道这一点,因为这种方法已经在发挥作用。

早期的网络协议在 30 多年后仍然有用,因为它们仍然是开源的、去中心化的、自主的和标准化的。但政府可以通过监管应用程序来限制通过这些协议的信息。或者他们可以保护信息的自由流动,就像美国通过批准 1996 年《通信道德法案》(Communications Decency Act)第 230 条所做的那样。每个国家都可以决定自己的方法,而在其各自管辖范围内运营浏览器、网站和应用程序的企业有能力定制产品以遵守这些决定。

由于协议和应用程序之间的二分法在 Web3 中是相同的,所以对 Web3 的监管方法应该保持不变。Web3 的应用程序,如钱包、网站应用程序和其他应用程序,使用户能够将数字资产存入借贷协议的流动性池,通过市场协议购买 NFT,并在 DEX 上交易资产。这些钱包、网站和应用程序可以在它们试图提供访问的每个司法管辖区受到监管,要求它们遵守法规是合理的。

第一代网络以网络、数据交换、电子邮件和文件传输协议的形式为我们提供了令人难以置信的工具,所有这些都使信息以互联网的速度移动成为可能。第三代网络使价值转移以这种速度发生成为可能,借贷和资产交换已经作为这种新互联网的原生功能而存在。这是一个令人难以置信的公共利益,必须得到保护。随着 Web3 从去中心化金融或 "DeFi" 扩展到视频游戏、社交媒体、创造者经济和 Gig 经济,为这些行业创造公平竞争环境的监管将变得更加重要。权衡所有的因素,正确的方法变得尤为明显。

应用程序应该受到监管,而不是协议。