a16z:如何识别、评估和避免DAO治理攻击?

原文作者:Pranav Garimidi;Scott Duke Kominers;Tim Roughgarden

原文编译:老雅痞

许多 Web3 项目使用可替换和可交易的原生代币进行无许可投票。无权限投票可以提供许多好处,从降低准入门槛到增加竞争。代币持有者可以使用他们的代币对一系列问题进行投票——从简单的参数调整到治理过程本身的大修。(关于 DAO 治理的评论,见 「光速民主」)但是无权限投票很容易受到治理攻击,即攻击者通过合法手段(如在公开市场上购买代币)获得投票权,但为了攻击者自己的利益,利用这种投票权来操纵协议。这些攻击是纯粹的 「协议内」,这意味着它们不能通过密码学解决。相反,防止它们需要周到的机制设计。为此,我们开发了一个框架,以帮助 DAO 评估威胁,并有可能对抗此类攻击。

实践中的治理攻击

治理攻击的问题并不只是理论上的。它们不仅可以在现实世界中发生,而且已经发生并将继续发生。

在一个突出的例子中,Steemit,一家在其区块链上建立去中心化社交网络的创业公司,Steem 有一个由 20 个证人控制的链上治理系统。投票者使用他们的 STEEM 代币(该平台的原生台币)来选择证人。在 Steemit 和 Steem 获得牵引力的同时,孙宇晨已经制定了将 Steem 合并到 Tron 的计划,Tron 是他在 2018 年创立的区块链协议。为了获得这样做的投票权,孙宇晨找到了 Steem 的创始人之一,并购买了相当于总供应量 30% 的代币。一旦当时的 Steem 证人发现他的购买行为,他们就冻结了孙宇晨的代币。接下来是孙宇晨和 Steem 之间的公开反击,以控制足够的代币来部署他们喜欢的前 20 名证人名单。在涉及主要交易所并花费数十万美元购买代币后,孙宇晨最终取得了胜利,并有效地自由控制了网络。

在另一个例子中,Beanstalk,一个稳定币协议,发现自己很容易受到通过 Flashloan 的治理攻击。一个攻击者通过贷款获得了足够多的 Beanstalk 的治理代币,瞬间通过了一个恶意提案,让他们夺取了 Beanstalk 的 1.82 亿美元的储备。与 Steem 攻击不同,这次攻击发生在一个区块的范围内,这意味着在任何人都没有时间做出反应之前就已经结束了。

虽然这两起攻击发生在公开场合和公众视线之下,但治理攻击也可以在很长一段时间内秘密进行。攻击者可能会创建许多匿名账户,慢慢积累治理代币,同时表现得与其他持有人一样,以避免被怀疑。事实上,鉴于许多 DAO 的选民参与度往往很低,这些账户可以长期处于休眠状态而不引起怀疑。从 DAO 的角度来看,攻击者的匿名账户可以促进健康水平的去中心化投票权的出现。但最终攻击者可能达到一个门槛,即这些虚假钱包有能力单方面控制治理,而社区却无法回应。同样,恶意行为者可能会在投票率足够低的时候获得足够的投票权来控制治理,然后在许多其他代币持有人不活跃的时候试图通过恶意的提案。

虽然我们可能认为所有的治理行动只是市场力量发挥作用的结果,但在实践中,治理有时会产生低效的结果,这是激励失败或协议设计中其他漏洞的结果。就像政府决策会被利益集团甚至是简单的惯性所控制一样,DAO 治理如果结构不当也会导致低劣的结果。

那么,我们如何通过机制设计来解决这种攻击?

根本的挑战:不可辨别性

代币分配的市场机制无法区分那些想为项目做出有价值贡献的用户和那些对破坏或以其他方式控制项目抱有很高价值的攻击者。在一个代币可以在公共市场上买卖的世界里,从市场的角度来看,这两个群体在行为上是不可区分的:都愿意以越来越高的价格购买大量的代币。

这种不可区分性问题意味着去中心化的治理不是免费的。相反,协议设计者在公开的去中心化治理和确保他们的系统免受寻求利用治理机制的攻击者的影响之间面临着基本的权衡。社区成员越是能自由地获得治理权力并影响协议,攻击者就越容易利用同一机制进行恶意修改。

这种不可辨别性的问题在权益证明(Proof of Stake)区块链网络的设计中很熟悉。在那里就是如此,代币的高流动性市场使得攻击者更容易获得足够的权益来破坏网络的安全保障。尽管如此,代币激励和流动性设计的混合使得权益证明网络成为可能。类似的策略可以帮助确保 DAO 协议的安全。

评估和解决脆弱性的框架

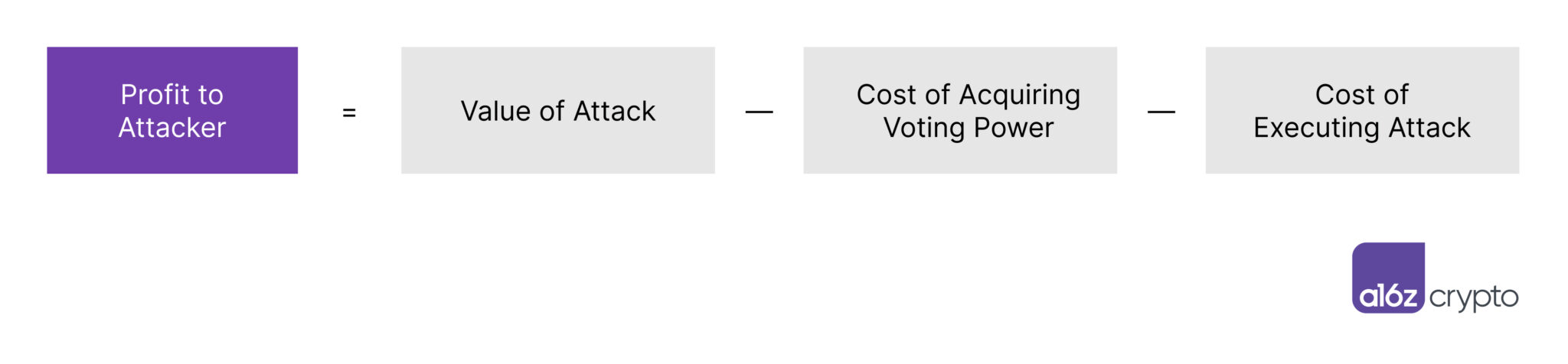

为了分析不同项目所面临的脆弱性,我们使用了一个由以下公式捕获的框架:

对于一个协议来说,要想被认为是对治理攻击的安全,攻击者的利润应该是负的。在为一个项目设计治理规则时,这个方程可以作为评估不同设计选择的影响的一个指导原则。为了减少利用协议的动机,该方程意味着三个明确的选择:降低攻击的价值,增加获得投票权的成本,以及增加执行攻击的成本。

降低攻击的价值

限制攻击的价值可能很困难,因为一个项目越成功,成功的攻击可能就越有价值。显然,一个项目不应该为了减少攻击的价值而故意破坏自己的成功。

然而,设计者可以通过限制治理所能做的范围来限制攻击的价值。如果治理只包括改变项目中某些参数的权力(例如,借贷协议的利率),那么潜在的攻击范围就比治理允许完全普遍控制治理的智能合约时要窄得多。

治理范围可以是一个项目阶段的功能。在其生命的早期,一个项目可能有更广泛的治理,因为它找到了自己的立足点,但实际上治理可能被创始团队和社区严格控制。随着项目的成熟和控制权的下放,在治理中引入一定程度的摩擦可能是有意义的——至少在最重要的决策中需要有大型全体会议。

增加获得投票权的成本

一个项目也可以采取措施,使其更难获得攻击所需的投票权。代币的流动性越强,就越容易要求获得投票权,因此,几乎是矛盾的,项目可能希望为了保护治理而减少流动性。人们可以尝试直接减少代币的短期交易性,但这在技术上可能是不可行的。

为了间接减少流动性,项目可以提供激励措施,使个别代币持有者不太愿意出售。这可以通过激励质押来实现,或者通过赋予代币独立的价值,超越纯粹的治理。代币持有人获得的价值越多,他们就越能与项目的成功保持一致。

独立的代币利益可能包括参加现场活动或社交体验。至关重要的是,像这样的好处对与项目保持一致的个人来说是高价值的,但对攻击者来说是无用的。提供这类好处提高了攻击者在获取代币时面临的有效价格:由于独立的好处,目前的持有人将不太愿意出售,这应该增加市场价格;然而,虽然攻击者必须支付更高的价格,但独立功能的存在并没有提高攻击者获取代币的价值。

增加执行攻击的成本

除了提高投票权的成本,还可以引入摩擦,使攻击者即使在获得代币后也难以行使投票权。例如,设计者可以要求对参与投票的用户进行某种认证,如 KYC(了解你的客户)检查或信誉评分阈值。我们甚至可以限制未经认证的行为者首先获得投票代币的能力,也许需要一些现有的验证者来证明新方的合法性。

在某种意义上,这正是许多项目分配其初始代币的方式,确保受信任的各方控制相当一部分的投票权。( 许多权益证明解决方案使用类似的技术来捍卫他们的安全 ——严格控制谁可以访问早期的权益,然后从那里逐渐去中心化。)

另外,项目可以让攻击者即使控制了大量的投票权,他们在通过恶意提案时仍然面临困难。例如,一些项目有时间锁,使一个代币在被交换后的一段时间内不能被用来投票。因此,寻求购买或借用大量代币的攻击者将面临着在实际投票前等待的额外成本——以及投票成员会注意到并在这期间挫败他们的预期攻击的风险。授权在这里也是有帮助的。通过给予积极但非恶意的参与者代表他们投票的权利,那些不想在治理中发挥特别积极作用的个人仍然可以为保护系统贡献他们的投票权。

一些项目使用否决权,允许投票推迟一段时间,以提醒不活跃的选民注意一个潜在的危险提案。在这样的方案下,即使攻击者提出恶意提案,投票者也有能力回应并关闭它。这些设计和类似的设计背后的想法是阻止攻击者偷偷摸摸地通过恶意提案,并为项目的社区提供时间来制定应对措施。理想情况下,那些明显符合协议利益的提案将不必面对这些路障。

例如,在 Nouns DAO,否决权由 Nouns 基金会掌握,直到 DAO 本身准备好实施一个替代模式。正如他们在网站上写的那样,「Nouns 基金会将否决那些给 Nouns DAO 或 Nouns 基金会带来非同小可的法律或生存风险的提案。」

项目必须取得平衡,允许对社区变化有一定程度的开放性(有时可能不受欢迎),同时不允许恶意提案从缝隙中溜走。往往只需要一个恶意的提议就可以搞垮一个协议,所以清楚地了解接受和拒绝提议的风险权衡是至关重要的。当然,在确保治理安全和使治理成为可能之间也存在着高水平的权衡——任何引入摩擦以阻止潜在攻击者的机制当然也会使治理过程更难使用。

我们在这里勾勒出的解决方案属于完全去中心化的治理和为了协议的整体健康而部分牺牲一些去中心化的理想之间的光谱。我们的框架突出了项目可以选择的不同路径,因为他们寻求确保治理攻击不会获利。我们希望社区能够利用这个框架,通过他们自己的实验进一步发展这些机制,使 DAO 在未来更加安全。